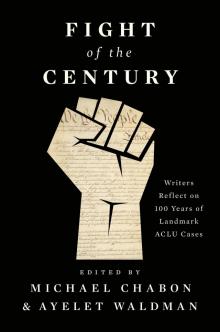

Fight of the Century

Michael Chabon

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

To the ACLU’s clients, who for over 100 years have refused to accept injustice and have chosen to fight for civil liberties and civil rights

Introduction

MICHAEL CHABON AND AYELET WALDMAN

Every year the moon is struck, and its cratered face forever marred, by tens of thousands of asteroids and meteors. At least that many bodies rain down on Earth over the same period, and yet the Earth has very few craters and endures only a handful of relatively insignificant impact events every year. The difference, of course, is that unlike the moon, the Earth is blessed with and enveloped by an atmosphere that constantly shields it from attack. The Bill of Rights serves a similar protective function for individual Americans and their civil liberties, which, like the Earth, are and have always been under constant, relentless attack. From Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 to Trump v. Hawaii in 2018, our federal and state governments—often abetted by the courts—have sought to curtail, constrain, and infringe on the rights defined and enshrined in James Madison’s remarkable document. The protections of liberty and equality it guarantees have always been menaced by the overweening instruments of state and majoritarian power. But lately, as in some science-fiction thriller where the Earth is threatened by a monstrous, meteor-spewing aberration in space-time, the rate and intensity of those attacks seem to be increasing. Meanwhile, agents of the government are at work doing what they can to dilute and undermine both our protective atmosphere and people’s belief in its integrity.

Things, we feel, have been getting worse. Liberty and equality are everywhere under attack. And that’s why the work of the American Civil Liberties Union feels more precious to us than ever before. The ACLU lawyers and staff are the brave souls who suit up, blast off, and do what they can to divert and repel all those incoming meteors, or blow them right out of the sky. We admire them. We admire them the way you must admire people who devote themselves to doing, to the utmost of their ability, any thankless, impossible, and absolutely essential job.

Liberty and justice for all. We used to stand up with our classmates every morning and timelessly pledge liberty and justice for all, even and especially for those (as the Supreme Court, agreeing with the ACLU, ruled in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette) whose consciences rebel at being compelled to pledge allegiance to a flag or to a country “under God.” The Bill of Rights protects pledgers and nonpledgers alike, but of course it is only the nonpledgers—the contrarians, the cranks, the nonconformists, the radicals and fanatics, the outsiders and the ostracized, the powerless and unpopular and imprisoned—who ever really need its protections. They also tend to be the ones least likely to receive those protections—not without a fight, anyway. That’s where the ACLU comes in.

The history of the ACLU is one of struggle, combat, of marginalized people and unpopular causes, of troublemakers and conscientious objectors, a history of battle and strife. But it is also the history of the very best our country has to offer to its citizens and, by way of example, to the rest of the world: the strong, golden strand of the Bill of Rights and the ideals it embodies, often frayed, occasionally snarled, stretched at times to the breaking point, but shining and unbroken down all the years since 1789. The ACLU holds the government, the courts, and the nation to their avowed and highest standard, insisting on the recognition of the protections the Constitution affords to every American, no matter how marginalized, no matter how unpopular the cause, even if the people it protects sometimes despise the freedom it represents.

As American Jews in our fifties, we both remember, powerfully, the moment we each first understood the austere and lonely fight of the ACLU, the thankless road to freedom on which it plies its trade. It was 1977, when the ACLU took on the case of the local branch of the American National Socialist Party, whose members wanted to hold a march along the main street of Skokie, a predominantly Jewish suburb outside Chicago. We remember wrestling with the difficult idea that the ACLU could be on the side of good (the First Amendment) and evil (Nazis) at the same time. To understand the vital role that the ACLU plays in American society requires a nuanced understanding of the absolute value of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom from unwarranted search and seizure, of the right to due process and equal justice under the law, even—again, especially—when those rights protect people we find abhorrent or speech that offends us.

Nuance unfortunately seems to be in very short supply nowadays. In these pages, we have collected essays by some of our country’s finest writers—not just because writers are and have long been among the principal beneficiaries and guardians of the First Amendment but also because they traffic, by temperament and trade, in nuance and its elucidation, in ambiguity and shades of gray. We turn to writers, here and in general, to help us understand and, even more, grasp both ends of ambiguities, to expand the scope of our vision to encompass the whole gray spectrum of human existence, in all its messy human detail.

Each of the writers in this book has chosen a seminal case in which the ACLU was involved, either as counsel or as amicus curiae—friend of the court—and made it the subject of an essay. Some have chosen to dig deep into the facts of the case and bring them vividly to life. Others have focused on their own personal experience with the civil liberty—and its abridgment—at issue by the case. Still others have crafted impassioned pleas on behalf of the rights being challenged or upheld in a particular Supreme Court case or have even, in at least one case, taken a reasoned position opposed to the ACLU’s own. Regardless of approach each of the writers has, we hope you will agree, produced something thoughtful, challenging, enlightening, and as worthy of your time as the ACLU is worthy of your support.

Enjoy.

Foreword

DAVID COLE

“The decisions of the courts have nothing to do with justice.” So proclaimed Morris Ernst, the ACLU’s first general counsel, in 1935. You won’t hear that from ACLU attorneys these days. The ACLU has spent the better part of its 100 years seeking justice from the courts—and often getting it. The cases that inspired the essays in this book are only a small selection of the ACLU’s victories. Over the course of the ACLU’s first century, the courts have recognized substantial safeguards for free speech and free press; protected religious minorities; declared segregation unconstitutional; guaranteed a woman’s right to decide when and whether to have children; recognized claims to equal treatment by women, gay men, and lesbians; directed states to provide indigent criminal defendants an attorney at state expense; regulated police searches and interrogations; and insisted on the rights to judicial review of immigrants facing deportation and even foreign “enemy combatants” held at Guantánamo in the war on terror. In thousands of cases brought or supported by the ACLU, the courts have extended the protections of privacy, dignity, autonomy, and equality to an ever-widening group of our fellow human beings. We can expect—and must demand—justi

ce from the courts.

Indeed, within days of the election of Donald Trump, the ACLU told the president-elect, “We’ll see you in court,” warning him that if he sought to implement the many unconstitutional promises he had made on the campaign trail, we would sue. He lived up to his promises, and so have we. In just the two and a half years since Trump took office, courts have repeatedly ruled against his administration’s rights-offending policies. Courts have declared illegal a raft of anti-immigrant initiatives, including separating children from their parents in hopes of deterring refugees from coming to the United States; detaining asylum seekers whether or not they pose any risk of flight or danger; and denying asylum to those who do not enter at a border checkpoint, even though the asylum statute expressly provides relief to all who face persecution at home, regardless of whether they entered the country lawfully or unlawfully. Courts primarily ruled invalid Trump’s effort to ban transgender individuals from the military. The Supreme Court blocked the Trump administration’s effort to ask about citizenship on the census, a tactic that would have led immigrant families not to fill out the form, causing communities with large immigrant populations to lose their fair share of representation and federal funding. The courts have halted an executive order that would authorize employers to deny contraceptive insurance coverage to their female employees if the employer objects on moral or religious grounds to facilitating such access. They have issued a nationwide injunction against the administration’s policy of barring young, undocumented women in federal custody access to abortion. They have stopped en masse deportation of young undocumented immigrants afforded temporary relief from deportation by President Barack Obama under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. They have stopped the administration from denying federal funds to cities and towns that adopt immigrant-friendly law enforcement policies. The Supreme Court rejected the Trump administration’s argument that citizens have no Fourth Amendment right against the government’s obtaining around-the-clock records of their whereabouts from their cell phone providers, ruling that the government must obtain a warrant based on probable cause of criminal wrongdoing to seek such information.

We don’t always get justice from the courts, of course. After multiple federal courts struck down all three versions of Trump’s ban on entry from several predominantly Muslim countries, the Supreme Court in 2018 upheld the third version of the ban by a 5–4 vote along partisan lines. In the same term, the Supreme Court ruled that immigration law permits extended detention of certain immigrants without even a hearing to determine whether they pose a flight risk or danger and that Ohio could strike voters from the rolls for failing to vote in two consecutive elections. And President Trump’s two appointments to the Supreme Court are almost certain to make it a less sympathetic forum for civil rights and liberties issues. But thus far, the courts have held off many of the Trump administration’s worst initiatives, upholding the rights of millions in the process.

Even a brief review of history demonstrates how far we have come. When the ACLU began in 1920, the Bill of Rights did not apply to state officials at all. It constrained only the federal government. Thus, state police arrests and searches did not violate the Fourth Amendment, no matter how abusive they were, and state legislatures did not violate the First Amendment, even if they directly prohibited unpopular speech. Even as to the federal government, the Bill of Rights offered only limited protections. Speech could be suppressed as long as it had a “bad tendency” to lead to criminal conduct. Under such terms, communists, anarchists, union leaders, and dissidents were targeted and penalized for their political beliefs. Newspapers were not protected from libel suits brought by government officials they had criticized in print. Despite the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, “separate but equal” was the law of the land. Women could be barred entry into the legal profession on the ground that the entire sex was too sensitive to handle the work. Criminal defendants had no right to the assistance of counsel, and if police gathered evidence illegally, they could use it against the defendant at trial. Practically the only constitutional right the Supreme Court recognized in the 1920s was the right of big businesses not to be subject to laws designed to protect workers and consumers from exploitation. No wonder Morris Ernst expressed such skepticism about the courts.

As the cases discussed in this book illustrate, much has changed in 100 years. While the process has been far from linear, rights have generally expanded, protecting more and more previously unprotected groups, recognizing as discrimination conduct once taken for granted, insisting on fair procedures where previously few rules applied, and expanding the freedoms of free speech and association, the core rights of a democracy. Indeed, the expansion of First Amendment rights has been so considerable that many of the recurring arguments today focus on whether the First Amendment is too protected (as Scott Turow suggests in his essay on campaign finance legislation). It is easy to focus on how far we still have to go, but it is important not to lose sight of how far civil liberties and civil rights have come.

The ACLU has been at the forefront of many of these struggles, but it has by no means acted alone. We have long worked in collaboration with a wide range of individuals and groups from across the political spectrum in defense of liberty. We are nonpartisan and ecumenical; if you support liberty, we are your ally. In some of the cases discussed in this book, the ACLU was lead counsel, and sister organizations supported our work by filing friend-of-the-court, or amicus, briefs. In others, the ACLU appeared as amicus curiae, while others took the lead. Unions played a central part in the initial expansion of First Amendment rights, work that was later joined by civil rights activists and groups, so often the targets of repression for their political views. We have worked with religious groups across the spectrum to defend religious freedom, with libertarians from the left and the right to defend privacy, and with civil rights groups to extend the promise of equality to all. The defense and advance of liberty is a team effort.

It is an honor that so many immensely talented writers have contributed to this book. It is also, in a sense, fitting. Cases are, after all, stories. Although they are about real people and real events, not imagined ones, a lawyer’s job is to weave a compelling narrative in the hope of persuading a court that an injustice has been done and that the court has the power to right the wrong—which it does by writing an opinion. The court is invited to provide, if not necessarily a happy ending, at least a just one—one that offers a measure of accountability. A lawsuit essentially asks the judge to finish the story. But, of course, the story is never really done, even after the Supreme Court rules. Just as the characters in novels and short stories generally go on at the story’s close to “live happily ever after” or not, so, too, the conclusion of a lawsuit is generally at most the end of a chapter. The parties go on, as do the struggles to make their rights meaningful.

Every case, moreover, is but one part of a larger narrative. Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation unconstitutional, but the challenge of ending segregation and achieving integration continues to this day. Roe v. Wade protected a woman’s right to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy in 1972, but the ACLU and others have been fighting ever since to preserve that protection in the face of repeated attacks. Gideon v. Wainwright ruled that poor criminal defendants have the right to the assistance of counsel, but providing meaningful representation to the poor remains elusive because public officials are unwilling to fund such services adequately. The Supreme Court in the 1970s answered Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s call, in her capacity as codirector of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, to recognize that treating people differently on the basis of sex violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. That legal recognition marked a major advance over earlier decisions upholding laws treating women differently because they were considered inherently the weaker sex. But to this day, women are paid less than men; suffer violence and harassment at the hands of male partners, bosses,

family members, and acquaintances; and are the subject of discriminatory stereotypes that limit their access to full equality. The Fourth Amendment requires the police to get a warrant from a magistrate based on probable cause of criminal activity in order to search a home, but preserving privacy in the digital age requires constant rethinking and revision of the rules that govern surveillance, as computers, cell phones, and the Internet make feasible forms of mass spying unimaginable to George Orwell in 1984, much less to the framers in 1789.

Cases, like novels, do not stand alone. They must be understood in context. Just as today’s novels must be read against and in relation to the great novels of prior generations, so too cases are just part of a larger campaign for justice, one that occurs in multiple forums outside the Supreme Court, including Congress, the White House, state legislatures and courts, town councils, corporate boardrooms, university campuses, and religious communities. We often focus on an individual lawsuit because it provides a compelling story, but to understand the development of constitutional rights, one must look further. It is no coincidence, for example, that the Supreme Court’s most significant expansion of equality rights came during the civil rights movement or that the Court first recognized sex discrimination as a constitutional violation in the midst of feminism’s second wave in the 1960s and 1970s. To understand how the right of marriage equality was attained, Andrew Sean Greer’s essay on United States v. Windsor points out that one must look beyond the immediate arguments advanced in the Supreme Court to decades of struggle outside the federal courts to advance the basic notion that a human being deserves equal dignity and respect regardless of whether he or she loves someone of the same or a different sex.

All of the essays contained here reflect this insight. Not a single author limits his or her discussion to the legal arguments made in the courtroom. Every writer finds some different way into the subject matter, and that point of entry links the case to a broader context. Many authors find echoes in their personal experiences, whether as a student of color attending a segregated school in Huntsville, Alabama (Yaa Gyasi), a young black woman “loitering” on Easter Sunday in DeLisle, Mississippi (Jesmyn Ward), a gay man marching in New York’s Saint Patrick’s Day parade (Michael Cunningham), the husband in a mixed marriage driving through Virginia (Aleksandar Hemon), a college student who protested Alexander Haig (Elizabeth Strout), or an author who just likes to use the word fuck and appreciates that the Supreme Court has said that he can (Jonathan Lethem). The fact that so many authors understand the cases through their personal experience underscores how deeply these disputes affect us all and how intertwined individual rights and liberties are in the fabric of all of our lives.