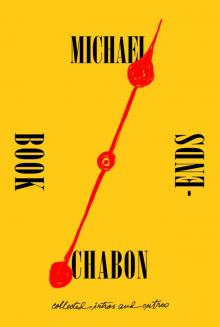

Bookends

Michael Chabon

Dedication

To Jennifer Barth

Epigraph

I remind you that all things are but a beginning, forever beginning.

—ST. ALIA OF THE KNIFE

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Meta-Introduction

Intros

The Wes Anderson Collection, Matt Zoller Seitz

Trickster Makes This World, Lewis Hyde

The Long Ships, Frans G. Bengtsson

Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy, Andrew Bolton

Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer, Ben Katchor

Herma, MacDonald Harris

Casting the Runes and Other Ghost Stories, M. R. James

Brown Sugar Kitchen, Tanya Holland

Monster Man, Gary Gianni

The Sailor on the Seas of Fate, Michael Moorcock

American Flagg!, Howard Chaykin

D’Aulaires’ Norse Myths, Ingri and Edgar Parin D’Aulaire

“The Rocket Man,” Ray Bradbury

John Carter of Mars: Warlord of Mars, Marv Wolfman, Gil Kane et al.

The Escapists, Brian K. Vaughan

Summerland

Fountain City, excerpt

Outros

Fountain City, excerpt

The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

Gentlemen of the Road

The Phantom Tollbooth, Norton Juster

Wonder When You’ll Miss Me, Amanda Davis

Appendix: Liner Notes

1980–1996, Carsickness

Uptown Special Vinyl Edition, Mark Ronson

About the Author

Also by Michael Chabon

Copyright

About the Publisher

Meta-Introduction

“I NEVER READ INTRODUCTIONS,” SAYS ROSE, THE YOUNGER OF my two daughters. She thinks it over for a second, frowns; the statement doesn’t quite ring true. She emends it: “Well, I’ve read two,” she says. One turns out to be Jack Kerouac’s introduction to Robert Frank’s The Americans, required reading for a photography class: “But it was fine because I like his style.” The other is Sherman Alexie’s introduction to his own The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (a favorite book, and author, of Rose’s), because “it felt like it would be rude not to.”

I suspect that my daughter’s antipathy toward introductions (we did not discuss postscripts) is fairly common among avid readers. People who never bother to read what is more properly styled a foreword (in which one writer presents the work of another) or a preface (in which the writer herself, often retrospectively, reflects on her own work) are likely as numerous as people who don’t bother with user manuals before launching the software application or powering up the widget.

You will not find me among either group; in the first instance out of hard experience but in the second out of love, pure love, from the time of my first encounter, circa 1979, with John Cheever’s all-too-brief preface to his Stories, which contains the following passage, in which I now detect a premonitory stirring, two decades ahead of schedule, of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay:

These stories seem at times to be stories of a long-lost world when the city of New York was still filled with a river light, when you heard the Benny Goodman quartets from a radio in the corner stationery store, and when almost everybody wore a hat.

Certain forewords—Susan Sontag’s to The Barthes Reader, Walter Benjamin’s to Fables of Leskov—and prefaces—Raymond Chandler’s to The Simple Art of Murder, Robert Towne’s to the published script of Chinatown, Elmore Leonard’s to his Complete Western Stories—have become beloved, even crucial texts for me, to be regularly re-read—as are Nabokov’s afterword to Lolita and Leigh Brackett’s to her Best of collection.

Some forewords are transitive: acts of seduction that are at the same time documents of earlier seductions. I already had a serious literary crush on Susan Sontag when I saw her name on the cover of The Barthes Reader and plunged into her foreword, at which point I discovered that Sontag, in turn, had a serious literary crush on this droll-looking Frenchman in his ubiquitous cardigan; I emerged from her foreword with a crush of my own on the late M. Barthes. Other forewords are parasitical; like cuckoos’ eggs laid in crows’ nests they hatch and flourish at the expense of their hosts. The fables of Nikolai Leskov are fine, if you like that sort of thing, but I can’t imagine life without “The Storyteller,” Benjamin’s preface to a German translation of that Russian classic. Benjamin’s diamantine epigrammatic style is on dazzling display throughout the piece but in no other writing of his does it do the work of heartbreak so powerfully as toward the end of the first section of “The Storyteller,” where Benjamin collapses all the industrialized brutality and disruption of the First World War into some fifty words:

A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.

But Benjamin’s cuckoo’s egg also had a lasting, personal effect on me, far more acute than anything I got from the Fables it nominally served to introduce. I used to worry, sometimes—in particular after I read Frank O’Connor’s seminal meditation on the short story, The Lonely Voice—that unlike James Joyce, Anton Chekhov, A. E. Coppard, and the other writers Frank O’Connor lionized in The Lonely Voice, I was not really from anywhere. My family had been on the move for three generations or more, on both sides, and by the age of twenty-five I had lived in more than a dozen different places. The distinction Benjamin draws, in his foreword to Leskov, between storytellers who stay put and accumulate stockpiles of local lore and those who travel the world collecting the material of the tales they bring home, went a long way to reassuring me that my rootlessness was not only a legitimate condition for writing but, potentially, a theme worth exploring in my work.

As for prefaces (and afterwords), these may be explanatory, apologetic, triumphal, tendentious, rueful, score-settling, spiteful, bibliographic, theoretical (as is the case with Chandler’s), or gently embarrassed (as is the case with Cheever’s) but the best of them—like Cheever’s—are also what I would call restorative. They unstopper the vial that contains, like some volatile oil, the fragrance of the time in which the prefaced work was engendered, conceived, or written, summoning for writer and reader alike a sensuous jolt of things past: Cheever’s Goodman-haunted stationery stores; the motels and dusty mountainsides of Nabokov’s midcentury transcontinental butterfly hunt; Towne’s ache for the smell of orange groves and all the lost Los Angeles that it encodes; and the Malibu, desolate and wild as Barsoom, of Leigh Brackett’s girlhood.

There are many reasons a writer might agree to provide an introduction to her own or another writer’s book: affection, gratitude, regret, revenge, enthusiasm, a desire to evangelize or set the record straight. I’ve done it for some of those reasons, and more. But the primary motivation for writing introductions has been the same as for everything I write: a hope of bringing pleasure to the reader—to some reader, somewhere. In this hope my sole assurance has been the pleasure I’ve taken as a reader, over the years, in the prefaces, forewords, and afterwords—the intros and outros—written by others. I’m aware that this assurance may be far from sufficient for many readers, however, and I would encourage skippers of introductions to put this book down and seek pleasure elsewhere—but what would be the point?

Intros

The Wes Anderson Collection, Matt Zoller Seitz

THE WORLD IS SO BIG, SO COMPLICATED, SO REPLETE WITH marvels and surprises that it takes years for most people to begin to notice that it is, also, irretrievably b

roken. We call this period of research “childhood.”

There follows a program of renewed inquiry, often involuntary, into the nature and effects of mortality, entropy, heartbreak, violence, failure, cowardice, duplicity, cruelty, and grief; the researcher learns their histories, and their bitter lessons, by heart. Along the way, he or she discovers that the world has been broken for as long as anyone can remember, and struggles to reconcile this fact with the ache of cosmic nostalgia that arises, from time to time, in the researcher’s heart: an intimation of vanished glory, of lost wholeness, a memory of the world unbroken. We call the moment at which this ache first arises “adolescence.” The feeling haunts people all their lives.

Everyone, sooner or later, gets a thorough schooling in brokenness. The question becomes: what to do with the pieces? Some people hunker down atop the local pile of ruins and make do, Bedouins tending their goats in the shade of shattered giants. Others set about breaking what remains of the world into bits ever smaller and more jagged, kicking through the rubble like kids running through piles of leaves. And some people, passing among the scattered pieces of that great overturned jigsaw puzzle, start to pick up a piece here, a piece there, with a vague yet irresistible notion that perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again.

Two difficulties with this latter scheme at once present themselves. First of all, we have only ever glimpsed, as if through half-closed lids, the picture on the lid of the jigsaw-puzzle box. Second, no matter how diligent we have been about picking up pieces along the way, we will never have anywhere near enough of them to finish the job. The most we can hope to accomplish with our handful of salvaged bits—the bittersweet harvest of observation and experience—is to build a little world of our own. A scale model of that mysterious original, unbroken, half-remembered. Of course, the worlds we build out of our store of fragments can only be approximations, partial and inaccurate. As representations of the vanished whole that haunts us, they must be accounted failures. And yet in that very failure, in their gaps and inaccuracies, they may yet be faithful maps, accurate scale models, of this beautiful and broken world. We call these scale models “works of art.”

In their set design and camerawork, their use of stop-motion, maps, and models, Wes Anderson’s films readily, even eagerly, concede the “miniature” quality of the worlds he builds. And yet these worlds span continents and decades. They comprise crime, adultery, brutality, suicide, the death of a parent, the drowning of a child, moments of profound joy and transcendence. Vladimir Nabokov, his life cleaved by exile, created a miniature version of the homeland he would never see again and tucked it, with a jeweler’s precision, into the housing of John Shade’s miniature epic of family sorrow. Anderson—who has suggested that the breakup of his parents’ marriage was a defining experience of his life—adopts a Nabokovian procedure with the families or quasi-families at the heart of all his films, from Rushmore forward, creating a series of scale-model households that, like the Zemblas and Estotilands and other lost “kingdoms by the sea” in Nabokov, intensify our experience of brokenness and loss by compressing them. That is the paradoxical power of the scale model; a child holding a globe has a more direct, more intuitive grasp of the earth’s scope and variety, of its local vastness and its cosmic tininess, than a man who spends a year in circumnavigation. Grief, at full-scale, is too big for us to take in; it literally cannot be comprehended. Anderson, like Nabokov, understands that distance can increase our understanding of grief, allowing us to see it whole. But distance does not—ought not—necessarily imply a withdrawal. In order to gain sufficient perspective on the pain of exile and the murder of his father, Nabokov did not, in writing Pale Fire, step back from them. He reduced their scale, and let his patience, his precision, his mastery of detail—detail, the god of the model-maker—do the rest. With each of his films, Anderson’s total command of detail—both the physical detail of his sets and costumes, and the emotional detail of the uniformly beautiful performances he elicits from his actors—has enabled him to increase the persuasiveness of his own family Zemblas, without sacrificing any of the paradoxical emotional power that distance affords.

Anderson’s films have frequently been compared to the boxed assemblages of Joseph Cornell’s, and it’s a useful comparison, as long as one bears in mind that the crucial element, in a Cornell box, is neither the imagery and objects it deploys, nor the romantic narratives it incorporates and undermines, nor the playfulness and precision with which its objects and narratives have been arranged. The important thing, in a Cornell box, is the box.

Cornell always took pains to construct his boxes himself; indeed the box is the only part of a Cornell work literally “made” by the artist. The box, to Cornell, is a gesture—it draws a boundary around the things it contains, and forces them into a defined relationship, not merely with each other, but with everything on the far side of the box. The box sets out the scale of a ratio, it mediates the halves of a metaphor. It makes explicit, in plain, handcrafted wood and glass, the yearning of a model-maker to analogize the world, and at the same time it frankly emphasizes the limitations, the confines, of his or her ability to do so.

The things in Anderson’s films that recall Cornell’s boxes—the strict, steady, four-square construction of individual shots, by which the cinematic frame becomes a Cornellian gesture, a box drawn around the world of the film; the teeming, gridded, curio-cabinet sets at the heart of Life Aquatic, Darjeeling, and Mr. Fox—are often cited as evidence of his work’s “artificiality,” at times with the implication, simple-minded and profoundly mistaken, that a high degree of artifice is somehow inimical to seriousness, to honest emotion, to so-called authenticity. All movies, of course, are equally artificial; it’s just that some are more honest about it than others. In this important sense, the hand-built, model-kit artifice on display behind the pane of an Anderson box is a guarantor of authenticity; indeed, I would argue that artifice, openly expressed, is the only true “authenticity” an artist can lay claim to.

Anderson’s films, like the boxes of Cornell, or the novels of Nabokov, understand and demonstrate that the magic of art, which renders beauty out of brokenness, disappointment, failure, decay, even ugliness and violence—is authentic only to the degree that it attempts to conceal neither the bleak facts nor the tricks employed in pulling off the presto chango. It is honest only to the degree that it builds its precise and inescapable box around its maker’s x:y-scale version of the world.

“For my next trick,” says Joseph Cornell, or Vladimir Nabokov, or Wes Anderson, “I have put the world into a box.” And when he opens the box, you see something dark and glittering, an orderly mess of shards, refuse, bits of junk and feather and butterfly wing, tokens and totems of memory, maps of exile, documentation of loss. And you say, leaning in, “The world!” (2013)

Trickster Makes This World, Lewis Hyde

A BOOK IS A MAP; THE TERRITORY IT CHARTS MAY BE “THE world,” or other books, or the mind of the cartographer. A great book maps all three territories at once, or rather persuades us that they—world, literature, and a single human imagination—are coextensive. Of course that isn’t true. A map, like all abstractions, is a kind of lie. The world outside our heads, and the world inside them, and the lines by which we represent inside and out, do not really correspond, any more than do a squirt of stars, a connect-the-dot plan of the constellations, and the tendency of our minds to see, in an apparent arc of stars, two fish struggling on a line.

A great book, therefore, is in part an act of deception, a tissue of lies: a trick. Indeed, it plays the fundamental human trick of finding, or discovering, or imposing meaning in the senseless, pattern in chaos, fish and princesses and monsters in the heavens. That act of deception is at root a self-deception, conscious and unconscious, and without it life would be—life is—a terrible, useless procedure bracketed by orgasm and putrefaction. Small wonder that we should have come, therefore, to revere the One who perpetrates that li

e, who embodies the contingent and in so doing lends it the appearance of necessity. His name is Trickster. And this great book, by Lewis Hyde, is a map of Trickster’s wanderings through literature, human history, and the rich, surprising territory of Hyde’s mind. I have never found a map whose reckoning, however tricksy, felt more true.

We have at various moments in our history of foolishness persuaded ourselves that we have outgrown mythology, found clever, distancing ways to package it, to handle it with the tools of irony or scholarship or literary effect, to reduce it to fairy tale, ornamentation, motif. We have, alternatively but with as little sense, sought to view the myths of our ancestors as a kind of secret key or users manual, a shortcut to the primal, the primitive, the natural, the repressed. I have been a lover of mythology all my life and both kinds of fool at various times, whether as a reader of Marvel’s The Mighty Thor or of Robert Graves’s The White Goddess. But in the end, in turns out, a myth is only a story, and a story is all we can count on for comfort here in this obscure and broken land between the first dazzle of consciousness and its final winking out. I am a mythophile by nature and a storyteller by profession, but before I read Trickster Makes This World I never truly understood that myths were only stories, and that stories were only lies, and that lies were all we had. In Trickster Makes This World, Hyde picks out one thread of ancient story and traces it, without post-Freudian archness or the sounding of Wiccan drums, across all its knots and frayings, from prehistory to Duchamp, from the escape narrative of Frederick Douglass to Hyde’s own encounter with Coyote in the American southwest. In the resultant net of knotted story he catches us up like fish caught in a cord of stars.

My work as a writer and as an inheritor of the human bag of lies has never quite recovered from the shock of my first encounter with Trickster Makes This World, which was only, in the end, an encounter with everything I already knew and had long possessed. It is in the way of confidence men and tricksters to sell you what you already own; but a great writer, in so doing, always finds a way to enrich you by the game. Before I read Trickster I felt lost among the territories of “genre” and “literary” fiction, wanting both to exalt and to entertain readers, to write like Marcel Proust and Robert E. Howard (multiplicands whose product may in fact be William Faulkner). I felt drawn to many paths at once, reeling blindfolded across the map of literature like a man seeking a piñata with a stick. After I read Trickster Makes This World I was not a bit less lost; I was still, like Trickster and all my fellow humans, trapped among the worlds, with, as one of our greatest Tricksters once put it, “No direction home.” But now I knew, and have since never forgotten, that I was born to wander along the borderlands. To err—that is, to wander—is human. And so is the act of making a story out of our purposeless wanderings, as if they mattered, as if they had a beginning, a middle, and an end. They don’t, but there is neither joy nor art nor pleasure to be made from saying so. Coyote wouldn’t waste his time on a paltry truth like that. (2010)