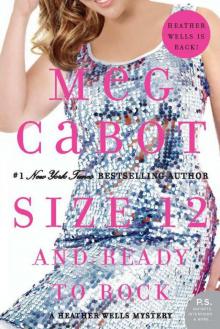

Size 12 and Ready to Rock

Meg Cabot

SIZE 12

AND READY TO ROCK

MEG

CABOT

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Acknowledgments

P.S.: Insights, Interviews & More . . .

About the book

Read on

About the Author

By Meg Cabot

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

Leave Alone

I’ve been called a fattie

I’ve been called big-boned

I’ve been called a leave-alone

As in “leave that one alone”

Sometimes love can suck

It can really, really suck

Sometimes love can suck

The life right out of you

Even fatties feel things

Big gals feel things too

And leave-alones feel so alone

Their hearts can break in two

Sometimes love can suck

It can really, really suck

But life has sucked a lot less

Since I finally met you

“Leave Alone”

Written by Heather Wells

Racing up the stairs to the second floor, my heart pounding—I’m a walker, not a runner. I try not to race anywhere unless it’s an emergency, and according to the call I received, that’s what this is—I find the corridor dark and deserted. I can’t see anything except the bloodred glow of the EXIT sign at the end of the hall. I can’t hear anything but the sound of my own heavy breathing.

They’re here, though. I can feel it in my bones. Only where?

Then it hits me. Of course. They’re behind me.

“Give it up,” I yell, kicking open the doors to the student library. “You’re so busted—”

The bullet hits me square in the back. Pain radiates up and down my spine.

“Ha!” shouts a masked man, springing out from an alcove. “I got you! You’re dead. So dead!”

Movie directors often cue their heroine’s death with flashbacks of the most significant moments from her life, birth to the present. (Let’s be honest, though: who remembers her own birth?)

This isn’t what happens to me. As I stand there dying, all I can think about is Lucy, my dog. Who’s going to take care of her when I’m gone?

Cooper. Of course, Cooper, my landlord and new fiancé. Except that our engagement isn’t so new anymore. It’s been three months since he proposed—not that we’ve told anyone about our plans to get married, because Cooper wants to elope in order to avoid his unbearable family—and Lucy’s grown so accustomed to finding him in my bed that she goes straight to him for her breakfast and morning walk, since he’s such an early riser, and I’m . . . not.

Actually, Lucy goes straight to Cooper for everything now because Cooper often works from home and spends all day with her while I’m here at Fischer Hall. To tell the truth, Lucy seems to like Cooper better than she likes me. Lucy’s a little bit of a traitor.

Lucy’s going to be so well taken care of after I’m dead that she probably won’t even notice I’m not there anymore. This is disheartening enough—or maybe encouraging enough—that my thoughts flicker irrationally to my doll collection. It’s mortifying that someone who is almost thirty owns enough dolls to form a collection. But I do, over two dozen of them, one from each of the countries in which I performed back when I was an embarrassingly overproduced teen pop singer for Cartwright Records. Since I wasn’t in any particular country long enough to sightsee—only to go on all the morning news shows, then give a concert, usually as the opening act for Easy Street, one of the most popular boy bands of all time—my mom got me a souvenir doll (wearing the country’s national costume) from each airport gift shop. She said this was better than seeing the koalas in Australia, or the Buddhist temples in Japan, or the volcanoes in Iceland, or the elephants in South Africa, and so on, because it saved time.

All this, of course, was before Dad got arrested for tax evasion, and Mom conveniently hooked up with my manager and then fled the country, taking with her the entire contents of my savings account.

“You poor kid.” That’s what Cooper said about the dolls the first time he spent the night in my room and noticed them staring down at him from the built-in shelves overhead. When I explained where they’d come from, and why I’d hung on to them for all these years—they’re all I have left of my shattered career and family, though Dad and I have been trying to reconnect since he got out of prison—Cooper had just shaken his head. “You poor, poor kid.”

I can’t die, I suddenly realize. Even if Cooper does take care of Lucy, he won’t know what to do with my dolls. I have to live, at least long enough to make sure my dolls go to someone who will appreciate them. Maybe someone from the Heather Wells Fan Club Facebook page. It has close to ten thousand likes.

Before I have a chance to figure out how I’m going to do this, however, another masked figure jumps out at me from behind a couch.

“Oh no!” she cries, shoving her protective eye shield to the top of her head. I’m more than a little surprised to see that it’s a student, Jamie Price. She looks horrified. “Gavin, it’s Heather. You shot Heather! Heather, I’m so sorry. We didn’t realize it was you.”

“Heather?” Gavin raises his own face mask, then lowers his gun. “Oh shit. My bad.”

I gather from his “my bad” that he means it’s his mistake that I’m dying from the large-caliber bullet he’s shot into my back. I feel a little bit badly for him because I know how much I meant to him, maybe even more than his own girlfriend, Jamie. Gavin’s probably going to require years of therapy to get over accidentally murdering me. He always seemed to relish his role in the May-December romance he imagined between us, even though our love was never going to happen. Gavin’s an undergrad film major, I’m the assistant director of his residence hall, and I’m in love with Cooper Cartwright . . . besides which, it’s against New York College policy for administrators to sleep with students.

Now, of course, our romance is definitely never going to happen, since Gavin’s shot me. I can feel the blood gushing from the wound in my back.

I’m not even sure how I’m still able to stand, given the size of the bloodstain and the fact that my spine is most likely severed. It’s a bit hard to see how deep the wound is, since the room—along with the rest of the second-floor library—is in darkness, except for what light is spilling in from the once-elegant casement windows overlooking Washington Square Park’s chess circle, two stories below.

“Gavin,” I say in a voice clogged with pain, “would you make sure my dolls go to someone who—”

Wait a minute.

“Is this paint?” I demand, bringing my fingers to my face so I can examine them more closely.

“We’re so sorry,” Jamie says sheepishly. “It says on the box that it washes easily out of most material

.”

“You’re playing paintball inside?” I do not feel sorry for Gavin anymore. In fact, I’m getting really pissed at Gavin. “And you think I’m worried about my clothes?”

Although truthfully, this shirt does happen to be one of my favorites. It’s loose over the parts I don’t necessarily want to show off (without making me look pregnant), while drawing attention to the areas I do want people to notice (boobs—mine are excellent). These are extremely rare qualities in a shirt. Jamie had better be right about the paint being washable.

“Jesus Christ, you guys. You could put someone’s eye out!”

I don’t care that I sound like the kid’s mom from that Christmas movie. I’m really annoyed. I’d been on the verge of asking Gavin McGoren to take care of my collection of dolls from many nations.

“Aw, c’mon,” Gavin says, regarding me wide-eyed. “You’ve been shot at before with live ammo, Heather. You can’t take a little paintball?”

“I never chose to put myself in a position where I could be shot at with live ammo,” I point out to him. “It isn’t part of my job description. It simply seems to happen to me a lot. Now would you please explain to me why Protection Services called me at home on a Sunday night to say there’s been a complaint about an unauthorized party—at which they claim someone has allegedly passed out—going on in a building that’s supposed to be empty for renovations for the summer, except for student staff workers?”

Gavin looks insulted. “It’s not a party,” he says. “It’s a paintball war.” He holds up his rifle as if it explains everything. “Fischer Hall desk and RA staff against the student paint crew. Here.” He disappears for a moment behind the couch, then reappears to pile a spare paintball gun, face shield, coveralls—doubtless stolen from the student paint crew—along with various other pieces of equipment into my arms. “Now that you’re here, you can be on the desk staff team.”

“Wait. This is what you guys did with the programming money I gave you?” I’m barely able to hide my disgust. I know from the class I’ve enrolled in this summer that it takes the human brain until the midtwenties to reach full maturation and structural development, which is why the young often make such questionable decisions.

But playing paintball inside a residence hall? This is a boneheaded move, even for Gavin McGoren.

I throw the paintball stuff back down on the couch.

“That money was supposed to go toward a pizza party,” I say. “Because you said all the dining halls are closed on Sunday nights and you never have enough money for anything to eat. Remember?”

“Oh no, no,” Jamie assures me. For a big girl, her voice can sound awfully babyish sometimes, maybe because she often ends her sentences on an up-note, like she’s asking a question even when she’s not. “We didn’t spend the money on paintball equipment, we checked it out free from the student sports center? I didn’t even know they had paintball equipment you could check out—probably because it’s always checked out during the school year when there’re so many people around?—but they do. All you have to do is leave your ID.”

“Of course,” I grumble. Why wouldn’t the college’s wealthy alumni have donated money to purchase paintball equipment for the students to check out for free? God forbid they’d donate it for something useful, like a science lab.

“Yeah,” Gavin says. “We did use the money on pizza. And beverages.” He holds up the remaining three cans of beer, dangling from the plastic rings of what was once a six-pack. “You wants? Only the best American-style lager for my womenz.”

I feel a burning sensation. It has nothing to do with the paintball with which I was recently shot. “Beer? You bought beer with money I gave you for pizza?”

“It’s Pabst Blue Ribbon,” Gavin says, looking confused. “I thought cool girl singer-songwriters were supposed to love the PBR.”

Perhaps because she’s noticed the anger sizzling in my eyes, Jamie walks over to give me a hug.

“Thanks so much for letting me stay here for the summer, Heather,” she says. “If I’d have had to spend it at home with my parents in Rock Ridge, I’d have died? Really. You have no idea what you’ve done for me. You’ve given me the wings I needed to fly. You’re the best boss ever, Heather.”

I have a pretty good idea what I’ve given Jamie, and it’s not wings. It’s free room and board for twelve weeks in exchange for twenty hours of work a week forwarding the mail of the residents who’ve gone home for the summer. Now, instead of having to commute into the city to see Gavin in secret (her parents don’t approve of him, since they think their daughter can do better than a scruffy-looking film major), Jamie can simply open her door, since he’s living right down the hall from her, as I’ve given him (unwisely, I’ve now decided) the same sweet deal.

“I’m pretty sure your parents wouldn’t agree I’m the best boss ever,” I say, resisting her hug. “I’m equally certain that if anyone in the Housing Office finds out about the paintball—and the beer—I’m not going to be anyone’s boss anymore.”

“What can they do to you?” Gavin asks indignantly. “We’re in a building that’s shut down for the summer, that’s going to be completely painted anyway, and we’re all over twenty-one. No one’s doing anything illegal.”

“Sure,” I say, sarcastically. “That’s why I got a call from Protection, because no one’s doing anything illegal.”

Gavin makes a face that looks particularly ghoulish with the protective shield still pushed back over his hair. “Was it Sarah?” he asks. “She’s the one who called in the complaint, wasn’t she? She’s always telling us to shut up because she’s trying to get her thesis finished, or whatever. I knew she wasn’t going to be cool with this.”

I don’t comment. I have no idea who ratted them out to the campus police. It could easily have been Sarah Rosenberg, Fischer Hall’s live-in graduate assistant assigned to respond to overnight emergencies and assist the hall director with nightly operations. Unfortunately, since the last one’s untimely demise, there’s no director of Fischer Hall for Sarah to assist. She’s been helping me supervise the student skeleton staff and waiting until Housing decides who our new hall director is going to be. I’ve already left one message for her—it’s weird that Sarah didn’t pick up, because she’s taking classes this summer and so is usually in her room. She has nothing to do but study, although she did acquire, around the time that I got secretly engaged, her first ever serious boyfriend.

“Look,” I say, taking out my cell phone to call Sarah again, “I didn’t give you guys that money for beer, and you know it. If there really is someone passed out, we need to find them right away and make sure they’re all right—”

“Oh, definitely,” Jamie says, looking worried. “But they can’t be passed out from drinking. We only bought two six-packs—”

“Well, the basketball team bought a bottle of vodka,” Gavin admits sheepishly.

“Gavin!” Jamie cries.

I feel as if I really have been shot, only this time in the head, not the spine, and with a real bullet. That’s the size of the migraine blooming behind my left eyeball. “What?” I say.

“Well, it’s not like I could stop ’em.” Gavin’s voice goes up an octave. “Have you seen how big they are? That one Russian kid, Magnus, is nearly seven feet tall. What was I going to say, ‘nyetski on the vodkaski’?”

Jamie thinks about this. “Wouldn’t it be ‘nyet’? And ‘vodka’? I think those are Russian words.”

“Fantastic,” I say, ignoring them as I press redial and call Sarah’s number again. “If any of those guys is the one who’s passed out, we’re not even going to be able to lift him onto a gurney. So where’s the basketball team right now?”

Gavin looks excited. He takes something from a pocket of his coveralls and goes to one of the casement windows. In the glow from the streetlamps outside, I see that he’s unfolding a floor plan of the building. It’s covered in mysterious notations made with red marker, presumably a plan for tonig

ht’s battle. My headache stabs me even harder. I should be home having Chinese takeout and watching Freaky Eaters with my boyfriend, our Sunday-night tradition, although for some reason Cooper fails to see the brilliance of Freaky Eaters, preferring to watch 60 Minutes, or as I like to call it, “The Show That Is Never About Freaky Eaters.”

“We’ll probably need to split up to find them,” Gavin says, lifting his beer and taking a swift sip before pointing at a location on the floor plan. “We set up a bunker in the library because we can hear anybody coming up the stairs from the lobby or taking the service elevator. We estimate Team Paint Crew is holing up somewhere on the first floor, most likely the cafeteria. But they could be in the basement, possibly the game room. My idea is, we get down there, then take out all of them at once, and win the whole game—”

“Wait,” Jamie says. “Did you hear that?”

“I didn’t hear anything,” Gavin says. “So here’s the plan. Jamie, you go down the back stairwell to the caf. Heather, you go down the front stairwell and see if anyone is hiding out in the basement.”

“You’ve been breathing too many chemicals in the darkroom at your summer film classes,” I say. Sarah’s phone has gone to voice mail again. Frustrated, I hang up without leaving another message. “And anyway, I’m not playing.”

“Heather, Heather, Heather,” Gavin says, chidingly. “Film is all digital now, no one uses darkrooms or chemicals. And you most certainly are playing. We killed you, so you’re our prisoner. You have to do what we say.”

“Seriously,” Jamie says. “Didn’t you guys hear that?”

“If you killed me, that means I’m dead,” I say. “So I shouldn’t have to play.”

“Those aren’t the rules,” Gavin says. “The way we’ll take them is, we go in through the dining office, then hide behind the salad bar—”