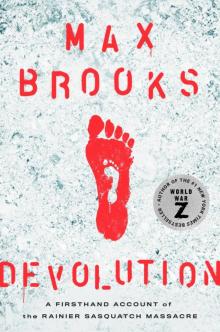

Devolution: A Firsthand Account of the Rainier Sasquatch Massacre

Max Brooks

Devolution is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Max Brooks

Map copyright © 2020 by David Lindroth Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

DEL REY is a registered trademark and the Circle colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Hardback ISBN 9781984826787

International edition ISBN 9781984820198

Ebook ISBN 9781984826794

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Will Staehle

Cover art: aga7ta/Shutterstock

ep_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Map

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Epilogue

Dedication

Acknowledgments

By Max Brooks

About the Author

What an ugly beast the ape, and how like us.

—MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO

BIGFOOT DESTROYS TOWN. That was the title of an article I received not long after the Mount Rainier eruption. I thought it was spam, the inevitable result of so much online research. At the time I was just finishing up what seemed like my hundredth op-ed on Rainier, analyzing every facet of what should have been a predictable, and preventable, calamity. Like the rest of the country, I needed facts, not sensationalism. Staying grounded had been the focus of so many op-eds, because of all Rainier’s human failures—political, economic, logistical—it was the psychological aspect, the hyperbole-fueled hysteria, that had ended up killing the most people. And here it was again, right on my laptop screen: BIGFOOT DESTROYS TOWN.

Just forget it, I told myself, the world’s not going to change overnight. Just breathe, delete, and move on.

And I almost did. Except for that one word.

“Bigfoot.”

The article, posted on an obscure, cryptozoological website, claimed that while the rest of the country was focused on Rainier’s wrath, a smaller but no less bloody disaster was occurring a few miles away in the isolated, high-end, high-tech eco-community of Greenloop. The article’s author, Frank McCray, described how the eruption not only cut Greenloop off from rescue, but also left it vulnerable to a troop of hungry, apelike creatures that were themselves fleeing the same catastrophe.

The details of the siege were recorded in the journal of Greenloop resident Kate Holland, the sister of Frank McCray.

“They never found her body,” McCray wrote to me in a follow-up email, “but if you can get her journal published, maybe someone will read it who might have seen her.”

When I asked why me, he responded, “Because I’ve been following your op-eds on Rainier. You don’t write anything you haven’t thoroughly researched first.” When I asked why he thought I’d have any interest in Bigfoot, he answered, “I read your Fangoria article.”

Clearly I wasn’t the only one who knew how to research a subject. Somehow, McCray had tracked down a decades-old list of my “Top Five Classic Bigfoot Movies” for the iconic horror magazine. In that piece, I’d talked about growing up “at the height of the Bigfoot frenzy,” challenging readers to watch these old movies “with the eyes of a six-year-old child, eyes that flick constantly from the terror on the screen to the dark, rustling trees outside the window.”

Reading that piece must have convinced McCray that some part of me wasn’t quite ready to leave my childhood obsession in the past. He must have also known that my adult skepticism would force me to thoroughly vet his story. Which I did. Before contacting McCray again, I discovered that there had been a highly publicized community known as Greenloop. There was an ample amount of press regarding its founding—and its founder, Tony Durant. Tony’s wife, Yvette, had also hosted several online yoga and meditation classes from the town’s Common House right up to the day of the eruption. But on that day, everything stopped.

That was not unusual for towns that lay in the path of Rainier’s boiling mudslides, but a quick check of the official FEMA map showed Greenloop had never been touched. And while devastated areas such as Orting and Puyallup had eventually reconnected their digital footprints, Greenloop remained a black hole. There were no press reports, no amateur recordings. Nothing. Even Google Earth, which has been so diligent in updating its satellite imagery of the area, still posts the original, pre-eruption photo of Greenloop and the surrounding area. As peculiar as all these red flags might be, what finally drove me back to McCray was the fact that the only mention of Greenloop after the disaster that I could find was in a local police report that said the official investigation was still “ongoing.”

“What do you know?” I asked him after several days of radio silence. That was when he sent me the link to an AirDrop link of a photo album taken by Senior Ranger Josephine Schell. Schell, who I would later interview for this project, had led the first search and rescue team into the charred wreckage of what had once been Greenloop. Amid the corpses and debris, she had discovered the journal of Kate Holland (née McCray) and had photographed each page before the original copy was removed.

At first, I still suspected a hoax. I’m old enough to remember the notorious “Hitler Diaries.” However, as I finished the last page, I couldn’t help but believe her story. I still do. Perhaps it’s the simplicity of her writing, the frustratingly credible ignorance of all things Sasquatch. Or perhaps it’s just my own irrational desire to exonerate the scared little boy I used to be. That’s why I’ve published Kate’s story, along with several news items and background interviews that I hope will provide some context for readers not familiar with Sasquatch lore. In the process of compiling that research, I struggled greatly with how much to include. There are literally dozens of scholars, hundreds of hunters, and thousands of recorded encounters. To wade through them all might have taken years, if not decades, and this story simply does not have that kind of time. That is why I have chosen to limit my interviews to the two people with direct, personal involvement in the case, and my literary references to Steve Morgan’s The Sasquatch Companion. Fellow Bigfoot enthusiasts will no doubt recognize Morgan’s Companion as the most comprehensive, up-to-date guidebook on the subject, combining historical accounts, recent eyewitne

ss sightings, and scientific analysis from experts like Dr. Jeff Meldrum, Ian Redmond, Robert Morgan (no relation), and the late Dr. Grover Krantz.

Some readers may also question my decision to omit certain geographical details regarding the exact location of Greenloop. This was done to discourage tourists and looters from contaminating what is still an active crime scene. With the exception of these details, and the necessary spelling and grammatical corrections, the journal of Kate Holland remains intact. My only regret is not being able to interview Kate’s psychotherapist (who encouraged her to begin writing this diary) on the grounds of patient confidentiality. And yet this psychotherapist’s silence seems, at least to me, like an admission of hope. After all, why would a doctor worry about the confidentiality of her patient if she didn’t believe that patient was still alive?

At the time of this writing, Kate has been missing for thirteen months. If nothing changes, this book’s publication date may see her disappearance lasting several years.

At present, I have no physical evidence to validate the story you are about to read. Maybe I’ve been duped by Frank McCray, or maybe we’ve both been duped by Josephine Schell. I will let you, the reader, judge for yourself if the following pages seem reasonably plausible, and like me, if they reawaken a terror long buried under the bed of youth.

Go into the woods to lose sight and memory of the crimes of your contemporaries.

—JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU

JOURNAL ENTRY #1

September 22

We’re here! Two days of driving, with one night in Medford, and we’re finally here. And it’s perfect. The houses really are arranged in a circle. Okay, duh, but you told me to not stop, not edit, not erase and go back. Which is why you encouraged paper and pen. No backspace key. “Just keep writing.” Okay. Whatever. We’re here.

I wish Frank could have been here. I can’t wait to call him tonight. I’m sure he’ll apologize again for being stuck at that conference in Guangzhou and I’ll tell him, again, that it doesn’t matter. He’s done so much for us already! Getting the house ready, all the FaceTime video tours. He’s right about them not doing this place justice. Especially the hiking trail. I wish he could have been there for that first walk I took today. It was magical.

Dan wouldn’t go. No surprise. He said he’d stay behind to help with the unpacking. He always says he’ll help. I told him I wanted, needed, to stretch my legs. Two days in the car! Worst drive ever! I shouldn’t have listened to the news the whole time. I know, “ration my current events, learn the facts but don’t obsess.” You’re right. I shouldn’t have. Venezuela again, the troop surge. Refugees. Another boat overturned in the Caribbean. So many boats. Hurricane season. At least it was the radio. If I hadn’t been driving, I’d have probably tried to watch on my phone.

I know. I know.

We should have at least taken the coastal road, like when Dan and I first got married. I should have pushed for that. But Dan thought the 5 was faster.

Ugh.

All that horrible industrial farming. All those poor cows crammed up against each other in the hot sun. The smell. You know I’m sensitive to odors. I felt like it was still in my clothes, my hair, up in my nostrils by the time we got here. I had to walk, feel the fresh air, work out the muscles in my neck.

I left Dan to do whatever and headed up the marked hiking trail behind our house. It’s really easy, a gradual incline with terraced, woodblock steps every hundred yards or so. It passes next to our neighbor’s house, and I saw her. The old lady. Sorry, older. Her hair was clearly gray. Short, I guess. I couldn’t tell from the kitchen window. She was doing something in front of the sink. She looked up and saw me. She smiled and waved. I smiled and waved back, but didn’t stop. Is that rude? I just figured, like unpacking, there’d be time to meet people. Okay, so maybe I didn’t actually think that. I didn’t really think. I just wanted to keep going. I felt a little guilty, but not for too long.

What I saw…

Okay, so remember how you thought sketching the layout of this place might help channel my need to organize my surroundings? I think that’s a good idea and if it’s halfway decent, I might text you the scanned picture. But there’s no way any drawing, or even photograph, can capture what I saw on that first hike.

The colors. Everything in L.A. is gray and brown. That gray, hazy bright sky that always hurt my eyes. The brown hills of dead grass that made me sneeze and made my head ache. It’s really green here, like back east. No. Better. So many shades. Frank told me there’d been a drought here and I thought I saw a little blond grass along the freeway, but way out here it’s like a rainbow of green—bright gold to dark blue. The bushes, the trees.

The trees.

I remember the first time I went hiking in Temescal Canyon back in L.A. Those short, gray twisted oaks with their small spiky leaves and thin, bullet-shaped acorns. They looked so hostile. It sounds super dramatic, but that’s how I felt. Like they were angry at having to live in that hot, hard, dusty dead clay.

These trees are happy. Yes, I said it. Why wouldn’t they be, in this rich, soft, rain-washed soil. A few with light, speckled bark and golden, falling leaves. They mix in among the tall, powerful pines. Some with their silver-bottom needles or the flatter, softer kind that brushed gently against me as I walked by. Comforting columns that hold up the sky, taller than anything in L.A., including those skinny wavy palms that hurt my neck to look up at.

How many times have we talked about the knot just under my right ear that runs down under my arm? It was gone. No matter how I craned my neck. No pain. And I hadn’t even taken anything. I’d planned to. I even left two Aleve waiting on the kitchen counter for when I got back. No need. Everything worked. My neck, my arm. Relaxed.

I stood there for maybe ten minutes or so, watching the sun shine through the leaves, noticing the bright, misty rays. Sparkling. I put my hand out to catch one, a little quarter-sized disc of warmth, pulling away my tension. Grounding me.

What did you say about OCD personalities? That we have such a hard time living in the present? Not here, not now. I could feel every second. Eyes closed. Deep cleansing breaths. The scented, moist, cool air. Alive. Natural.

So different from transplanted L.A. with lawns and palms and people living on someone else’s stolen water. It’s supposed to be a desert, not a sprawling vanity garden. Maybe that’s why everyone there is so miserable. They know they’re all living in a sham.

Not me. Not anymore.

I remember thinking, This can’t get any better. But it did. I opened my eyes and saw a large, emerald-tinted bush a few steps away. I’d missed it before. A berry bush! They looked like blackberries but I went online just to be sure. (Great Wi-Fi reception by the way, even so far from the house!) They were the real thing, and a crazy lucky find! Frank had said something about this summer’s drought killing the wild berry harvest. And yet here was this bush, right in front of me. Waiting for me. Remember how you told me to be more open to opportunities, to look for signs?

It didn’t matter that they were the tiniest bit tart. In fact, it made them even better. The taste took me back to the blueberry bush behind our house in Columbia.*1 How I could never wait till August when they’d ripen, how I’d just have to sneak half-purple beads in July. All those memories came rushing back, all those summers, Dad reading Blueberries for Sal and me laughing at when she runs into the bear. That was when my nose began to sting and the corners of my eyes started watering. I probably would have lost it right there, but, literally, a little bird saved me.

Actually two. I noticed a pair of hummingbirds flittering around these tall purple wildflowers sprouting in a Disneyesque patch of sun. I saw one stop at a flower and then the other buzzed right next to it, and then the most darling thing happened. The second one started giving the first little kisses, moving back and forth with its coppery orange f

eathers and pinkish red throat.

Okay, so I know you’re probably sick of comparisons by now. Sorry. But I can’t help thinking of those parrots. Remember them? The ones we talked about? The wild flock? Remember how we spent an entire session talking about how their squawking drove me crazy? I’m sorry if I didn’t see the connection you were trying to make.

Those poor things. They sounded so scared and angry. And why wouldn’t they? What else should they feel when some horrible person released them into an environment they weren’t born for? And their kids? Hatched with this gnawing discomfort in their genes. Every cell craving an environment they couldn’t find. They didn’t belong there! Nothing did! Hard to see what’s wrong until you hold it up to what’s right. This place, with its tall, healthy trees and happy little birds trading love kisses. Everything that’s here belongs here.

I belong here.

From the American Public Media radio show Marketplace. Transcript of host Kai Ryssdal’s interview with Greenloop founder Tony Durant.

RYSSDAL: But why would someone, particularly someone used to urban or even suburban life, choose to isolate themselves so far out in the wilderness?

TONY: We’re not isolated at all. During the week, I’m talking to people all around the world, and on the weekends, my wife and I are usually in Seattle.

RYSSDAL: But the time you have to spend driving to Seattle—

TONY: Is nothing compared to how many hours people waste in their cars every day. Think about how much time you spend driving back and forth to work, either ignoring or actively resenting the city around you. Living out in the country, we get to appreciate our city time because it’s voluntary instead of mandatory, a treat instead of a chore. Greenloop’s revolutionary living style allows us to have the best parts of both an urban and rural lifestyle.