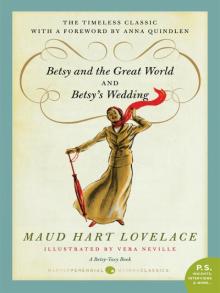

Betsy and the Great World / Betsy's Wedding

Maud Hart Lovelace

Betsy and the Great World

and

Betsy’s Wedding

Maud Hart Lovelace

Illustrated by Vera Neville

Table of Contents

Foreword

Betsy and the Great World

Betsy’s Wedding

Maud Hart Lovelace and Her World

About Betsy and the Great World

About Betsy’s Wedding

Whatever Happened To…

About the Author

Other Books by in The Betsy-Tacy Books

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

When I was first asked to speak about Maud Hart Lovelace I had to reread all ten of my Betsy-Tacy books. I would like to make this sound like a hardship, but most of you know better. There are three authors whose body of work I have reread more than once over my adult life: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, and Maud Hart Lovelace. It was, as always, a pleasure and delight.

And the truth is that I have been preparing for this speech, in a variety of ways, for thirty years, and especially for the last ten. That was the decade in which I began to examine most closely what it meant to be a feminist in America, as I am, and why I felt so strongly that the women’s movement and what I believe it stands for has changed my life.

Many of those issues have been explored in my column in The New York Times, and over and over again I have tried to reinforce a simple message that I believe has been distorted, muddled, misunderstood, and just plain lied about in recent years by those who want women to go, not forward, but backward.

And that is that feminism is about choices. It is about women choosing for themselves which life roles they wish to pursue. It is about deciding who does and gets and merits and earns and succeeds in what by smarts, capabilities, and heart—not by gender. It is about honoring individuals because of their humanity, not their physiology.

And that is why my theme today is: Betsy Ray, Feminist Icon.

Could there be better books, and could there be a better girl, adolescent, young woman, to teach us all those things about choices than the Betsy-Tacy books and Betsy herself, along with her widely disparate circle of Tacy and Tib, Julia and Margaret, Mrs. Ray and Anna the hired girl, Mrs. Poppy and Miss Mix, Carney and Winona, Miss Bangeter and Miss Clarke? All these different women, who go so many different ways, with false starts and stops, with disappointments and limitations, and yet a sense that they can find a place for themselves in the world.

Do you realize that not once, in any book, does any individual, male or female, suggest to Betsy that she cannot, as she so hopes to do, become a writer? Can anyone possibly appreciate the impact that made on a child like me, wanting it too but seeing all around me on the bookshelves the names of men and seeing all around me in my house the domesticated ways of women?

In the early books, of course, this is not what we see. We see prototypes, really, as surely as Snow White and Rose Red, or Cinderella and her stepsisters. We see three little girls who begin as types: the shy and earnest one; the no-nonsense and literal one; and the ringleader, the storyteller, the adventurer, the center—Elizabeth Warrington Ray. Then the adventures and, more important, the traditions begin—the picnics on the Big Hill, the forays to little Syria, the shopping trips at Christmastime, and Betsy’s sheets of foolscap piling up in her Uncle Keith’s old trunk.

The books are simply stories of small town life and enduring friendship among little girls, and so it is easy to overlook their importance as teaching tools. But consider the alternatives to children in the early grades. The images of girls tend, overwhelmingly, to be of fairy princesses spinning straw into gold or sleeping until they are awakened by a prince.

Even the best ones usually show us caricatures instead of characters. Recently, for example, I wrote an introduction for a fiftieth anniversary edition of Madeline (Viking, 1989). It is one of my favorite picture books for children, has been since I myself was a child, mostly because of one line which sums up the rest of it: “To the tiger in the zoo Madeline just said ‘Pooh, pooh.’”

Madeline, unlike the straw-spinning princesses, has attitude. She is nobody’s fool.

But attitude, truth to tell, is a surface, two-dimensional characteristic, attractive as it may be. The stories of Betsy, Tacy, and Tib transcend attitude just as the simplistic drawings of the early books give way to the more realistic (albeit, to my mind, slightly oversweet) pictures. They are ultimately books about character, and especially about the character of one girl whose greatest sin, throughout the books, is to undervalue herself.

For those are the mistakes Betsy finds she cannot forgive, when she sells herself short, when she is not all she can be. As opposed to the shy, retiring, and respectful girl who became so valued in girl’s fiction, Betsy does best when she serves herself, when she is true to herself. In this she most resembles two other fictional heroines who, not surprisingly, also long to be writers and take their work very seriously indeed. One is Anne Shirley of the Anne of Green Gables books, and the other is Jo March of Little Women.

But the key difference, I think, is a critical one. Both Anne and Jo are implicitly made to pay in those books for the fact that they do not conform to feminine norms. Anne begins life as an orphan and never is permitted to forget that she must work for a living—in fact, you might call her the Joe Willard of girls, although she is far less prickly and far more easy to like than Joe Willard. Jo March of Little Women habitually reminds herself how unattractive she is and settles down, in one of the most unconvincing matches in fiction, with the older, most unromantic Professor Bhaer. It is her beautiful sister Amy who gets the real guy, the rich and romantic Laurie.

Betsy, by contrast, never had to pay for the sin of being herself; in fact, she only finds herself under a cloud when she is less than herself. At base, she is a charmed soul from beginning to end because she can laugh at herself and take herself seriously at the same time, because she is serious but never a prig, and interested in boys but never a flirt. Can anyone forget the moment when, returning from the sophomore dance at Schiller Hall with that absolute poop Phil Brandish trying to worm his fist into her pocket, she turns to him with desperation and blurts out, “You might as well know. I don’t hold hands.”

In fact it’s probably in that book, Betsy in Spite of Herself, that we see Betsy most the way I think we were always meant to see her, as a girl who will do what is right for her, not necessarily what the world wants her to do. But first, like most of us, she has to do what is wrong for her to find out what is right. She decides to nab Phil just for the fun of it, and to that end she adds the letter E to the end of her perfectly good name, sprays herself with Jockey Club perfume, and uses green stationery to write notes instead of her poetry or stories. It’s inevitable—when the real Betsy sneaks out, in the form of a song parody she and Tacy invented before the Phil/Betsy affair began, they break up. But instead of a sore heart, Betsy is left with Shakespeare: “This above all: to thine own self be true.”

Betsy already knows, as do we, that that self varies widely from girl to girl, that there is no little box that will fit them all. In Heaven to Betsy, she says, in the passage that made the future so clear and yet so mysterious for me:

She had been almost appalled, when she started going around with Carney and Bonnie, to discover how fixed and definite their ideas of marriage were. They both had cedar hope chests and took pleasure in embroidering their initials on towels to lay away. Each one had picked out a silver pattern and they were planning to give each other spoons in these patterns for Christmases and birthdays. When Betsy and Tacy and Tib talked about their

future they planned to be writers, dancers, circus acrobats.

Betsy never looks down on those aspirations of Carney and Bonnie’s. But she never looks away from her own aspirations. She follows a sensible progression from writing, to dreaming of being a writer, to actually saying she is going to be one, to sending her stories (when she is a mere senior in high school) to various women’s magazines. She makes the mistake so many of us make—like Jo in Little Women, she learns early on that writing about debutantes in Park Avenue penthouses is doomed to failure if you’ve neither debuted nor visited Park Avenue—but her gumption carries her through.

And there are, interestingly, no naysayers among her family members. While the Rays have three daughters, early on two of them are already committed to having careers outside the home, Julia as an opera singer, Betsy as a writer. Betsy’s parents are totally committed to this idea for them both, sending Julia to the Twin Cities and even to Europe to further her training as a singer, and arguing vociferously that Betsy’s work is as good as any that appears in popular magazines.

The idea of something that is yours to do became narrower and narrower as my mother grew up. As Betty Friedan wrote in The Feminine Mystique (Dell, 1963), by the time my mother was ready to enter what Julia always called The Great World, it had narrowed to one role and one role alone, that of wife and mother.

I don’t know when exactly I knew that that was never going to be enough for me. But I know where I got the idea that more was possible. It wasn’t from career women or role models—when I was a girl, there really weren’t any.

I learned it from books, and none more than from the stories about Betsy, Tacy, and Tib. Because the most important thing about Betsy Ray is that she has a profound sense of confidence and her own worth.

Of course, if this had been wrapped in a sanctimonious, plaster saint package, Betsy would have been—perish the thought—Elsie Dinsmore, the perfect, boring little girl of popular fiction who Betsy herself once mocks. And, if there had been no boys in the books, I, for one, wouldn’t have read them.

But we did read them, many of us, for so many reasons: because Maud Hart Lovelace had a real gift for adapting the prose to the appropriate age level, and the themes, too; because we fell in love, not only with Betsy but with Tacy and Tib and all the others, and wanted to know from year to year what was happening to them; because of Magic Wavers and Sunday night sandwiches and smoky coffee brewed out of doors and all the other little ordinary things that, in some fashion, became our ordinary things.

And because they were just like us.

But we know there are many us’s, with many different goals and aspirations. For many years those goals and aspirations were truncated by one simple fact: our sex. Everything around us reflected that, from who sat on the Supreme Court, to who listened to our chests when we were sick, to who oversaw services when we went to church on Sunday.

But from time to time we encountered a teacher, or a parent, or even a book that told us that we should let our ambitions fly, that we should believe in ourselves, that the only limits we should put on what we tried for were the limits of our desires and our talents. When I told people I was going to give this speech, most had never heard of Betsy-Tacy, and I had to describe them as a series of books for girls. But they were so much more than that to one little girl who grew up to be a woman writer and who, perhaps, learned that she could by the example given inside these books.

—ANNA QUINDLEN

(Adapted from a speech given to the Twin

Cities Chapter of the Betsy-Tacy Society

on June 12, 1993)

Betsy and the Great World

For

ELIZABETH LESLIE

Contents

1. Traveling Alone

2. “Haply I May Remember”

3. “And Haply May Forget”

4. Enchanted Island

5. The Deluge

6. The Captain’s Ball

7. The Diner d’Adieu

8. Travel Is Broadening

9. Miss Surprise’s Surprise

10. Betsy Makes a Friend

11. Betsy Takes a Bath

12. Three’s Not a Crowd

13. Dark Fairy Tale

14. A Very Special Doll

15. A Short Stay in Heaven

16. Betsy Curls Her Hair

17. Forgetting Again

18. The Second Moon in Venice

19. Betsy Writes a Letter

20. The Roll of Drums

21. The Agony Column

1

Traveling Alone

“Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne,

He travels the fastest who travels alone.”

BETSY WAS CHANTING IT under her breath to give herself courage as, laden with camera, handbag, umbrella, and Complete Pocket Guide to Europe, she started up the gangplank to the deck of the S.S. Columbic.

Behind her was a barnlike structure, crowded with carriages, automobiles, baggage carts, and milling distracted passengers. Before her loomed the great bulk of the liner. Thirteen thousand tons of it, according to the advertisements over which she had pored—far, far back in Minnesota. It had layers of decks, a smokestack in the center, and tall masts flying flags. She could smell the waters of Boston Harbor—cold, salty, fishy—into which she would presently be sailing.

“‘Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne…’” Her teeth were almost chattering. Not from cold, for she wore furs over her long tight coat and carried a muff. Fur trimmed, too, was her hat. She shivered because she was shaky inside, fearful and bewildered.

“‘He travels the fastest who travels alone…’” She wasn’t alone, exactly. A porter had seized her suit cases, and he strode beside her shoulder. But he was a stranger, like the throngs of people all around her. And they all seemed to be in groups—sociable, laughing, chattering groups.

Of course, Betsy, too, would be with someone else shortly. Her father and mother had seen to that. A bachelor professor and his unmarried sister, friends of Betsy’s father’s brother, had agreed to keep an eye on her during the voyage. But at her first meeting with them, this morning at the Parker House, she had managed to convey the impression that their chaperonage was extremely nominal. And when they had suggested that she join them for some travel later, she had been purposefully vague. It wasn’t her idea to go through Europe with the Wilsons, kind as they were, and homesick as she already was.

“Tacy ought to be here,” she thought forlornly.

She and Tacy had planned trips through all the long years of their friendship. They had planned to go around the world together, to see the Taj Mahal by moonlight, to go to the top of the Himalayas and up the Amazon, and above all to live in Paris…with ladies’ maids.

Celeste and Hortense, they had christened their maids…imaginary ones, of course.

“Thank goodness I have Celeste, at least,” Betsy muttered. For Tacy had faithlessly married. Julia was married too. Betsy had been her older sister’s maid of honor in December.

It was January now, 1914.

“Julia settling down!” Betsy scoffed.

Julia wasn’t, of course, settling down. A singer, she had married a flutist, and they planned to pursue their careers together. But Betsy was in no mood to be fair. The confusion on deck was more subtly terrifying even than the tumult below. The well-dressed men, the women with corsage bouquets blooming on their shoulders, seemed so assured, so gaily sufficient to themselves and one another, so completely indifferent to the great adventure of one Betsy Ray, aged twenty-one, from Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The porter turned her over to a uniformed steward. She was taken below decks, along labyrinthine corridors, carpeted, smelling of the sea, to her stateroom, Number 52.

Number 52! They had selected it back in Minneapolis. She remembered the chart on the travel agent’s desk and her family rejoicing because this stateroom had a porthole giving on the ocean.

There it was, the porthole! And the room was a small white affair wi

th a washstand and two bunks, one above the other. Miss Wilson would have the lower one. Betsy’s steamer trunk had already been placed in a corner. The steward put her bags on it, and she tipped him, trying to act casual.

Back on deck, she secured a steamer chair—Julia had told her that was the first thing to do. But what about her ticket? Shouldn’t she give that to someone? She found the office of the purser.

He was very busy, besieged from all sides, but when she said with anxious dignity, “I’m Miss Elizabeth Ray,” he turned quickly.

“And it’s Miss Betsy Ray herself,” he remarked surprisingly.

He spoke with an Irish inflection and he looked the Irishman, too…smooth black hair with a touch of gray at the temples, blue eyes with a light in them, a dimple in his chin.

Betsy felt her color rising. How maddening to blush before his gay assurance!

“I beg your pardon?” she said and remembered to sink into her debutante slouch.

This fashionable pose became her, for she was very slender. (Some girls had to wear special corsets to get the debutante slouch.) She was glad her fur boa was tossed lightly over her shoulder.

Mr. O’Farrell—that was the name above his window—continued to look at her.

“Faith, and I’m inter-r-r-ested to meet you!” He rolled his r’s in a fascinating way. “Letters to Miss Betsy Ray take up half that mountain of mail in the library yonder.”