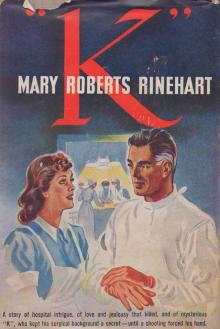

K

Mary Roberts Rinehart

Produced by David Brannan

K

By Mary Roberts Rinehart

CHAPTER I

The Street stretched away north and south in two lines of ancienthouses that seemed to meet in the distance. The man found it infinitelyinviting. It had the well-worn look of an old coat, shabby butcomfortable. The thought of coming there to live pleased him. Surelyhere would be peace--long evenings in which to read, quiet nights inwhich to sleep and forget. It was an impression of home, really, thatit gave. The man did not know that, or care particularly. He had beenwandering about a long time--not in years, for he was less than thirty.But it seemed a very long time.

At the little house no one had seemed to think about references. Hecould have given one or two, of a sort. He had gone to considerabletrouble to get them; and now, not to have them asked for--

There was a house across and a little way down the Street, with a cardin the window that said: "Meals, twenty-five cents." Evidently themidday meal was over; men who looked like clerks and small shopkeeperswere hurrying away. The Nottingham curtains were pinned back, and justinside the window a throaty barytone was singing:

"Home is the hunter, home from the hill: And the sailor, home from sea."

Across the Street, the man smiled grimly--Home!

For perhaps an hour Joe Drummond had been wandering up and down theStreet. His straw hat was set on the back of his head, for the eveningwas warm; his slender shoulders, squared and resolute at eight, by ninehad taken on a disconsolate droop. Under a street lamp he consulted hiswatch, but even without that he knew what the hour was. Prayer meetingat the corner church was over; boys of his own age were rangingthemselves along the curb, waiting for the girl of the moment. When shecame, a youth would appear miraculously beside her, and the world-oldpairing off would have taken place.

The Street emptied. The boy wiped the warm band of his hat and slappedit on his head again. She was always treating him like this--keeping himhanging about, and then coming out, perfectly calm and certain thathe would still be waiting. By George, he'd fool her, for once: he'd goaway, and let her worry. She WOULD worry. She hated to hurt anyone. Ah!

Across the Street, under an old ailanthus tree, was the house hewatched, a small brick, with shallow wooden steps and--curiousarchitecture of Middle West sixties--a wooden cellar door beside thesteps.

In some curious way it preserved an air of distinction among its morepretentious neighbors, much as a very old lady may now and then lendtone to a smart gathering. On either side of it, the taller houses hadan appearance of protection rather than of patronage. It was a matterof self-respect, perhaps. No windows on the Street were so spotlesslycurtained, no doormat so accurately placed, no "yard" in the rear sotidy with morning-glory vines over the whitewashed fence.

The June moon had risen, sending broken shafts of white light throughthe ailanthus to the house door. When the girl came at last, she steppedout into a world of soft lights and wavering shadows, fragrant with treeblossoms not yet overpowering, hushed of its daylight sounds of playingchildren and moving traffic.

The house had been warm. Her brown hair lay moist on her forehead, herthin white dress was turned in at the throat. She stood on the steps,the door closed behind her, and threw out her arms in a swift gesture tothe cool air. The moonlight clothed her as with a garment. From acrossthe Street the boy watched her with adoring, humble eyes. All hiscourage was for those hours when he was not with her.

"Hello, Joe."

"Hello, Sidney."

He crossed over, emerging out of the shadows into her envelopingradiance. His ardent young eyes worshiped her as he stood on thepavement.

"I'm late. I was taking out bastings for mother."

"Oh, that's all right."

Sidney sat down on the doorstep, and the boy dropped at her feet.

"I thought of going to prayer meeting, but mother was tired. WasChristine there?"

"Yes; Palmer Howe took her home."

He was at his ease now. He had discarded his hat, and lay back on hiselbows, ostensibly to look at the moon. Actually his brown eyes restedon the face of the girl above him. He was very happy. "He's crazy aboutChris. She's good-looking, but she's not my sort."

"Pray, what IS your sort?"

"You."

She laughed softly. "You're a goose, Joe!"

She settled herself more comfortably on the doorstep and drew alongbreath.

"How tired I am! Oh--I haven't told you. We've taken a roomer!"

"A what?"

"A roomer." She was half apologetic. The Street did not approve ofroomers. "It will help with the rent. It's my doing, really. Mother isscandalized."

"A woman?"

"A man."

"What sort of man?"

"How do I know? He is coming tonight. I'll tell you in a week."

Joe was sitting bolt upright now, a little white.

"Is he young?"

"He's a good bit older than you, but that's not saying he's old."

Joe was twenty-one, and sensitive of his youth.

"He'll be crazy about you in two days."

She broke into delighted laughter.

"I'll not fall in love with him--you can be certain of that. He is talland very solemn. His hair is quite gray over his ears."

Joe cheered.

"What's his name?"

"K. Le Moyne."

"K.?"

"That's what he said."

Interest in the roomer died away. The boy fell into the ecstasy ofcontent that always came with Sidney's presence. His inarticulate youngsoul was swelling with thoughts that he did not know how to put intowords. It was easy enough to plan conversations with Sidney when he wasaway from her. But, at her feet, with her soft skirts touching him asshe moved, her eager face turned to him, he was miserably speechless.

Unexpectedly, Sidney yawned. He was outraged.

"If you're sleepy--"

"Don't be silly. I love having you. I sat up late last night, reading.I wonder what you think of this: one of the characters in the book I wasreading says that every man who--who cares for a woman leaves his markon her! I suppose she tries to become what he thinks she is, for thetime anyhow, and is never just her old self again."

She said "cares for" instead of "loves." It is one of the traditions ofyouth to avoid the direct issue in life's greatest game. Perhaps"love" is left to the fervent vocabulary of the lover. Certainly, as iftreading on dangerous ground, Sidney avoided it.

"Every man! How many men are supposed to care for a woman, anyhow?"

"Well, there's the boy who--likes her when they're both young."

A bit of innocent mischief this, but Joe straightened.

"Then they both outgrow that foolishness. After that there are usuallytwo rivals, and she marries one of them--that's three. And--"

"Why do they always outgrow that foolishness?" His voice was unsteady.

"Oh, I don't know. One's ideas change. Anyhow, I'm only telling you whatthe book said."

"It's a silly book."

"I don't believe it's true," she confessed. "When I got started I justread on. I was curious."

More eager than curious, had she only known. She was fairly vibrant withthe zest of living. Sitting on the steps of the little brick house,her busy mind was carrying her on to where, beyond the Street, with itsdingy lamps and blossoming ailanthus, lay the world that was some day tolie to her hand. Not ambition called her, but life.

The boy was different. Where her future lay visualized before her,heroic deeds, great ambitions, wide charity, he planned years with her,selfish, contented years. As different as smug, satisfied summer fromvisionary, palpitating spring, he was for her--but she was for all theworld.

By shifting his position his lips came close to her bare young arm. Ittempted him.<

br />

"Don't read that nonsense," he said, his eyes on the arm. "And--I'llnever outgrow my foolishness about you, Sidney."

Then, because he could not help it, he bent over and kissed her arm.

She was just eighteen, and Joe's devotion was very pleasant. Shethrilled to the touch of his lips on her flesh; but she drew her armaway.

"Please--I don't like that sort of thing."

"Why not?" His voice was husky.

"It isn't right. Besides, the neighbors are always looking out thewindows."

The drop from her high standard of right and wrong to the neighbors'curiosity appealed suddenly to her sense of humor. She threw back herhead and laughed. He joined her, after an uncomfortable moment. But hewas very much in earnest. He sat, bent forward, turning his new strawhat in his hands.

"I guess you know how I feel. Some of the fellows have crushes on girlsand get over them. I'm not like that. Since the first day I saw you I'venever looked at another girl. Books can say what they like: there arepeople like that, and I'm one of them."

There was a touch of dogged pathos in his voice. He was that sort, andSidney knew it. Fidelity and tenderness--those would be hers if shemarried him. He would always be there when she wanted him, looking ather with loving eyes, a trifle wistful sometimes because of his lack ofthose very qualities he so admired in her--her wit, her resourcefulness,her humor. But he would be there, not strong, perhaps, but always loyal.

"I thought, perhaps," said Joe, growing red and white, and talking tothe hat, "that some day, when we're older, you--you might be willing tomarry me, Sid. I'd be awfully good to you."

It hurt her to say no. Indeed, she could not bring herself to say it.In all her short life she had never willfully inflicted a wound.And because she was young, and did not realize that there is a shortcruelty, like the surgeon's, that is mercy in the end, she temporized.

"There is such a lot of time before we need think of such things! Can'twe just go on the way we are?"

"I'm not very happy the way we are."

"Why, Joe!"

"Well, I'm not"--doggedly. "You're pretty and attractive. When I see afellow staring at you, and I'd like to smash his face for him, I haven'tthe right."

"And a precious good thing for you that you haven't!" cried Sidney,rather shocked.

There was silence for a moment between them. Sidney, to tell the truth,was obsessed by a vision of Joe, young and hot-eyed, being haled to thepolice station by virtue of his betrothal responsibilities. The boy wasvacillating between relief at having spoken and a heaviness of spiritthat came from Sidney's lack of enthusiastic response.

"Well, what do you think about it?"

"If you are asking me to give you permission to waylay and assault everyman who dares to look at me--"

"I guess this is all a joke to you."

She leaned over and put a tender hand on his arm.

"I don't want to hurt you; but, Joe, I don't want to be engaged yet.I don't want to think about marrying. There's such a lot to do in theworld first. There's such a lot to see and be."

"Where?" he demanded bitterly. "Here on this Street? Do you wantmore time to pull bastings for your mother? Or to slave for your AuntHarriet? Or to run up and down stairs, carrying towels to roomers? Marryme and let me take care of you."

Once again her dangerous sense of humor threatened her. He lookedso boyish, sitting there with the moonlight on his bright hair, soinadequate to carry out his magnificent offer. Two or three of thestar blossoms from the tree had fallen all his head. She lifted themcarefully away.

"Let me take care of myself for a while. I've never lived my own life.You know what I mean. I'm not unhappy; but I want to do something.And some day I shall,--not anything big; I know. I can't do that,--butsomething useful. Then, after years and years, if you still want me,I'll come back to you."

"How soon?"

"How can I know that now? But it will be a long time."

He drew a long breath and got up. All the joy had gone out of the summernight for him, poor lad. He glanced down the Street, where Palmer Howehad gone home happily with Sidney's friend Christine. Palmer wouldalways know how he stood with Christine. She would never talk aboutdoing things, or being things. Either she would marry Palmer or shewould not. But Sidney was not like that. A fellow did not even caressher easily. When he had only kissed her arm--He trembled a little at thememory.

"I shall always want you," he said. "Only--you will never come back."

It had not occurred to either of them that this coming back, sotragically considered, was dependent on an entirely problematical goingaway. Nothing, that early summer night, seemed more unlikely than thatSidney would ever be free to live her own life. The Street, stretchingaway to the north and to the south in two lines of houses that seemedto meet in the distance, hemmed her in. She had been born in the littlebrick house, and, as she was of it, so it was of her. Her hands hadsmoothed and painted the pine floors; her hands had put up the twine onwhich the morning-glories in the yard covered the fences; had, indeed,with what agonies of slacking lime and adding blueing, whitewashed thefence itself!

"She's capable," Aunt Harriet had grumblingly admitted, watching fromher sewing-machine Sidney's strong young arms at this humble springtask.

"She's wonderful!" her mother had said, as she bent over her hand work.She was not strong enough to run the sewing-machine.

So Joe Drummond stood on the pavement and saw his dream of taking Sidneyin his arms fade into an indefinite futurity.

"I'm not going to give you up," he said doggedly. "When you come back,I'll be waiting."

The shock being over, and things only postponed, he dramatized his griefa trifle, thrust his hands savagely into his pockets, and scowled downthe Street. In the line of his vision, his quick eye caught a tinymoving shadow, lost it, found it again.

"Great Scott! There goes Reginald!" he cried, and ran after the shadow."Watch for the McKees' cat!"

Sidney was running by that time; they were gaining. Their quarry, afour-inch chipmunk, hesitated, gave a protesting squeak, and was caughtin Sidney's hand.

"You wretch!" she cried. "You miserable little beast--with catseverywhere, and not a nut for miles!"

"That reminds me,"--Joe put a hand into his pocket,--"I brought somechestnuts for him, and forgot them. Here."

Reginald's escape had rather knocked the tragedy out of the evening.True, Sidney would not marry him for years, but she had practicallypromised to sometime. And when one is twenty-one, and it is a summernight, and life stretches eternities ahead, what are a few years more orless?

Sidney was holding the tiny squirrel in warm, protecting hands. Shesmiled up at the boy.

"Good-night, Joe."

"Good-night. I say, Sidney, it's more than half an engagement. Won't youkiss me good-night?"

She hesitated, flushed and palpitating. Kisses were rare in the staidlittle household to which she belonged.

"I--I think not."

"Please! I'm not very happy, and it will be something to remember."

Perhaps, after all, Sidney's first kiss would have gone without herheart,--which was a thing she had determined would never happen,--goneout of sheer pity. But a tall figure loomed out of the shadows andapproached with quick strides.

"The roomer!" cried Sidney, and backed away.

"Damn the roomer!"

Poor Joe, with the summer evening quite spoiled, with no caress toremember, and with a potential rival who possessed both the years andthe inches he lacked, coming up the Street!

The roomer advanced steadily. When he reached the doorstep, Sidneywas demurely seated and quite alone. The roomer, who had walkedfast, stopped and took off his hat. He looked very warm. He carrieda suitcase, which was as it should be. The men of the Street alwayscarried their own luggage, except the younger Wilson across the way. Histastes were known to be luxurious.

"Hot, isn't it?" Sidney inquired, after a formal greeting. She indicatedthe place on the step just vacated by Joe.

"You'd better cool off outhere. The house is like an oven. I think I should have warned you ofthat before you took the room. These little houses with low roofs arefearfully hot."

The new roomer hesitated. The steps were very low, and he was tall.Besides, he did not care to establish any relations with the peoplein the house. Long evenings in which to read, quiet nights in which tosleep and forget--these were the things he had come for.

But Sidney had moved over and was smiling up at him. He folded upawkwardly on the low step. He seemed much too big for the house. Sidneyhad a panicky thought of the little room upstairs.

"I don't mind heat. I--I suppose I don't think about it," said theroomer, rather surprised at himself.

Reginald, having finished his chestnut, squeaked for another. The roomerstarted.

"Just Reginald--my ground-squirrel." Sidney was skinning a nut with herstrong white teeth. "That's another thing I should have told you. I'mafraid you'll be sorry you took the room."

The roomer smiled in the shadow.

"I'm beginning to think that YOU are sorry."

She was all anxiety to reassure him:--

"It's because of Reginald. He lives under my--under your bureau. He'sreally not troublesome; but he's building a nest under the bureau,and if you don't know about him, it's rather unsettling to see a paperpattern from the sewing-room, or a piece of cloth, moving across thefloor."

Mr. Le Moyne thought it might be very interesting. "Although, if there'snest-building going on, isn't it--er--possible that Reginald is a ladyground-squirrel?"

Sidney was rather distressed, and, seeing this, he hastened to add that,for all he knew, all ground-squirrels built nests, regardless of sex.As a matter of fact, it developed that he knew nothing whatever ofground-squirrels. Sidney was relieved. She chatted gayly of the tinycreature--of his rescue in the woods from a crowd of little boys, of hisrestoration to health and spirits, and of her expectation, when he wasquite strong, of taking him to the woods and freeing him.

Le Moyne, listening attentively, began to be interested. His quick mindhad grasped the fact that it was the girl's bedroom he had taken. Otherthings he had gathered that afternoon from the humming sewing-machine,from Sidney's businesslike way of renting the little room, from theglimpse of a woman in a sunny window, bent over a needle. Genteelpoverty was what it meant, and more--the constant drain of disheartened,middle-aged women on the youth and courage of the girl beside him.

K. Le Moyne, who was living his own tragedy those days, what withpoverty and other things, sat on the doorstep while Sidney talked, andswore a quiet oath to be no further weight on the girl's buoyant spirit.And, since determining on a virtue is halfway to gaining it, his voicelost its perfunctory note. He had no intention of letting the Streetencroach on him. He had built up a wall between himself and the rest ofthe world, and he would not scale it. But he held no grudge against it.Let others get what they could out of living.

Sidney, suddenly practical, broke in on his thoughts:--

"Where are you going to get your meals?"

"I hadn't thought about it. I can stop in somewhere on my way downtown.I work in the gas office--I don't believe I told you. It's ratherhaphazard--not the gas office, but the eating. However, it'sconvenient."

"It's very bad for you," said Sidney, with decision. "It leads toslovenly habits, such as going without when you're in a hurry, and thatsort of thing. The only thing is to have some one expecting you at acertain time."

"It sounds like marriage." He was lazily amused.

"It sounds like Mrs. McKee's boarding-house at the corner. Twenty-onemeals for five dollars, and a ticket to punch. Tillie, the dining-roomgirl, punches for every meal you get. If you miss any meals, your ticketis good until it is punched. But Mrs. McKee doesn't like it if youmiss."

"Mrs. McKee for me," said Le Moyne. "I daresay, if I knowthat--er--Tillie is waiting with the punch, I'll be fairly regular to mymeals."

It was growing late. The Street, which mistrusted night air, even on ahot summer evening, was closing its windows. Reginald, having eatenhis fill, had cuddled in the warm hollow of Sidney's lap, and slept.By shifting his position, the man was able to see the girl's face. Verylovely it was, he thought. Very pure, almost radiant--and young. Fromthe middle age of his almost thirty years, she was a child. There hadbeen a boy in the shadows when he came up the Street. Of course therewould be a boy--a nice, clear-eyed chap--

Sidney was looking at the moon. With that dreamer's part of her that shehad inherited from her dead and gone father, she was quietly worshipingthe night. But her busy brain was working, too,--the practical brainthat she had got from her mother's side.

"What about your washing?" she inquired unexpectedly.

K. Le Moyne, who had built a wall between himself and the world, hadalready married her to the youth of the shadows, and was feeling an oddsense of loss.

"Washing?"

"I suppose you've been sending things to the laundry, and--what do youdo about your stockings?"

"Buy cheap ones and throw 'em away when they're worn out." There seemedto be no reserve with this surprising young person.

"And buttons?"

"Use safety-pins. When they're closed one can button over them as wellas--"

"I think," said Sidney, "that it is quite time some one took a littlecare of you. If you will give Katie, our maid, twenty-five cents a week,she'll do your washing and not tear your things to ribbons. And I'llmend them."

Sheer stupefaction was K. Le Moyne's. After a moment:--

"You're really rather wonderful, Miss Page. Here am I, lodged, fed,washed, ironed, and mended for seven dollars and seventy-five cents aweek!"

"I hope," said Sidney severely, "that you'll put what you save in thebank."

He was still somewhat dazed when he went up the narrow staircase tohis swept and garnished room. Never, in all of a life that had beenactive,--until recently,--had he been so conscious of friendliness andkindly interest. He expanded under it. Some of the tired lines left hisface. Under the gas chandelier, he straightened and threw out his arms.Then he reached down into his coat pocket and drew out a wide-awake andsuspicious Reginald.

"Good-night, Reggie!" he said. "Good-night, old top!" He hardlyrecognized his own voice. It was quite cheerful, although the littleroom was hot, and although, when he stood, he had a perilous feelingthat the ceiling was close above. He deposited Reginald carefully onthe floor in front of the bureau, and the squirrel, after eyeing him,retreated to its nest.

It was late when K. Le Moyne retired to bed. Wrapped in a paper andsecurely tied for the morning's disposal, was considerable masculineunderclothing, ragged and buttonless. Not for worlds would he have hadSidney discover his threadbare inner condition. "New underwear for yourstomorrow, K. Le Moyne," he said to himself, as he unknotted his cravat."New underwear, and something besides K. for a first name."

He pondered over that for a time, taking off his shoes slowly andthinking hard. "Kenneth, King, Kerr--" None of them appealed to him.And, after all, what did it matter? The old heaviness came over him.

He dropped a shoe, and Reginald, who had gained enough courage to emergeand sit upright on the fender, fell over backward.

Sidney did not sleep much that night. She lay awake, gazing into thescented darkness, her arms under her head. Love had come into her lifeat last. A man--only Joe, of course, but it was not the boy himself, butwhat he stood for, that thrilled her had asked her to be his wife.

In her little back room, with the sweetness of the tree blossomsstealing through the open window, Sidney faced the great mystery of lifeand love, and flung out warm young arms. Joe would be thinking of hernow, as she thought of him. Or would he have gone to sleep, secure inher half promise? Did he really love her?

The desire to be loved! There was coming to Sidney a time when lovewould mean, not receiving, but giving--the divine fire instead of thepale flame of youth. At last she slept.

A night breeze came through the windows and spread coolness th

roughthe little house. The ailanthus tree waved in the moonlight and sentsprawling shadows over the wall of K. Le Moyne's bedroom. In the yardthe leaves of the morning-glory vines quivered as if under the touch ofa friendly hand.

K. Le Moyne slept diagonally in his bed, being very long. In sleep thelines were smoothed out of his face. He looked like a tired, overgrownboy. And while he slept the ground-squirrel ravaged the pockets of hisshabby coat.