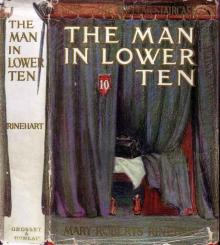

The Man in Lower Ten

Mary Roberts Rinehart

THE MAN IN LOWER TEN

By Mary Roberts Rinehart

CONTENTS

I I GO TO PITTSBURG

II A TORN TELEGRAM

III ACROSS THE AISLE

IV NUMBERS SEVEN AND NINE

V THE WOMAN IN THE NEXT CAR

VI THE GIRL IN BLUE

VII A FINE GOLD CHAIN

VIII THE SECOND SECTION

IX THE HALCYON BREAKFAST

X MISS WEST'S REQUEST

XI THE NAME WAS SULLIVAN

XII THE GOLD BAG

XIII FADED ROSES

XIV THE TRAP-DOOR

XV THE CINEMATOGRAPH

XVI THE SHADOW OF A GIRL

XVII AT THE FARM-HOUSE AGAIN

XVIII A NEW WORLD

XIX AT THE TABLE NEXT

XX THE NOTES AND A BARGAIN

XXI MCKNIGHT'S THEORY

XXII AT THE BOARDING-HOUSE

XXIII A NIGHT AT THE LAURELS

XXIV HIS WIFE'S FATHER

XXV AT THE STATION

XXVI ON TO RICHMOND

XXVII THE SEA, THE SAND, THE STARS

XXVIII ALISON'S STORY

XXIX IN THE DINING-ROOM

XXX FINER DETAILS

XXXI AND ONLY ONE ARM

THE MAN IN LOWER TEN

CHAPTER I. I GO TO PITTSBURG

McKnight is gradually taking over the criminal end of the business. Inever liked it, and since the strange case of the man in lower ten, Ihave been a bit squeamish. Given a case like that, where you canbuild up a network of clues that absolutely incriminate three entirelydifferent people, only one of whom can be guilty, and your faith incircumstantial evidence dies of overcrowding. I never see a shivering,white-faced wretch in the prisoners' dock that I do not hark back withshuddering horror to the strange events on the Pullman car Ontario,between Washington and Pittsburg, on the night of September ninth, last.

McKnight could tell the story a great deal better than I, althoughhe can not spell three consecutive words correctly. But, while he hasimagination and humor, he is lazy.

"It didn't happen to me, anyhow," he protested, when I put it up tohim. "And nobody cares for second-hand thrills. Besides, you want theunvarnished and ungarnished truth, and I'm no hand for that. I'm alawyer."

So am I, although there have been times when my assumption in thatparticular has been disputed. I am unmarried, and just old enough todance with the grown-up little sisters of the girls I used to know. Iam fond of outdoors, prefer horses to the aforesaid grown-up littlesisters, am without sentiment (am crossed out and was substituted.-Ed.)and completely ruled and frequently routed by my housekeeper, an elderlywidow.

In fact, of all the men of my acquaintance, I was probably the mostprosaic, the least adventurous, the one man in a hundred who would belikely to go without a deviation from the normal through the orderlyprocession of the seasons, summer suits to winter flannels, golf tobridge.

So it was a queer freak of the demons of chance to perch on myunsusceptible thirty-year-old chest, tie me up with a crime, ticketme with a love affair, and start me on that sensational and not alwaysrespectable journey that ended so surprisingly less than three weekslater in the firm's private office. It had been the most remarkableperiod of my life. I would neither give it up nor live it again underany inducement, and yet all that I lost was some twenty yards off mydrive!

It was really McKnight's turn to make the next journey. I had atournament at Chevy Chase for Saturday, and a short yacht cruise plannedfor Sunday, and when a man has been grinding at statute law for a week,he needs relaxation. But McKnight begged off. It was not the first timehe had shirked that summer in order to run down to Richmond, and I wassurly about it. But this time he had a new excuse. "I wouldn't be ableto look after the business if I did go," he said. He has a sort ofwide-eyed frankness that makes one ashamed to doubt him. "I'm always carsick crossing the mountains. It's a fact, Lollie. See-sawing over thepeaks does it. Why, crossing the Alleghany Mountains has the Gulf Streamto Bermuda beaten to a frazzle."

So I gave him up finally and went home to pack. He came later in theevening with his machine, the Cannonball, to take me to the station, andhe brought the forged notes in the Bronson case.

"Guard them with your life," he warned me. "They are more preciousthan honor. Sew them in your chest protector, or wherever people keepvaluables. I never keep any. I'll not be happy until I see GentlemanAndy doing the lockstep."

He sat down on my clean collars, found my cigarettes and struck a matchon the mahogany bed post with one movement.

"Where's the Pirate?" he demanded. The Pirate is my housekeeper, Mrs.Klopton, a very worthy woman, so labeled--and libeled--because of aferocious pair of eyes and what McKnight called a bucaneering nose. Iquietly closed the door into the hall.

"Keep your voice down, Richey," I said. "She is looking for the eveningpaper to see if it is going to rain. She has my raincoat and an umbrellawaiting in the hall."

The collars being damaged beyond repair, he left them and went to thewindow. He stood there for some time, staring at the blackness thatrepresented the wall of the house next door.

"It's raining now," he said over his shoulder, and closed the windowand the shutters. Something in his voice made me glance up, but he waswatching me, his hands idly in his pockets.

"Who lives next door?" he inquired in a perfunctory tone, after a pause.I was packing my razor.

"House is empty," I returned absently. "If the landlord would put it insome sort of shape---"

"Did you put those notes in your pocket?" he broke in.

"Yes." I was impatient. "Along with my certificates of registration,baptism and vaccination. Whoever wants them will have to steal my coatto get them."

"Well, I would move them, if I were you. Somebody in the next house wasconfoundedly anxious to see where you put them. Somebody right at thatwindow opposite."

I scoffed at the idea, but nevertheless I moved the papers, puttingthem in my traveling-bag, well down at the bottom. McKnight watched meuneasily.

"I have a hunch that you are going to have trouble," he said, as Ilocked the alligator bag. "Darned if I like starting anything importanton Friday."

"You have a congenital dislike to start anything on any old day," Iretorted, still sore from my lost Saturday. "And if you knew the ownerof that house as I do you would know that if there was any one at thatwindow he is paying rent for the privilege."

Mrs. Klopton rapped at the door and spoke discreetly from the hall.

"Did Mr. McKnight bring the evening paper?" she inquired.

"Sorry, but I didn't, Mrs. Klopton," McKnight called. "The Cubs won,three to nothing." He listened, grinning, as she moved away with littleirritated rustles of her black silk gown.

I finished my packing, changed my collar and was ready to go. Then verycautiously we put out the light and opened the shutters. The windowacross was merely a deeper black in the darkness. It was closed anddirty. And yet, probably owing to Richey's suggestion, I had an uneasysensation of eyes staring across at me. The next moment we were at thedoor, poised for flight.

"We'll have to run for it," I said in a whisper. "She's down there witha package of some sort, sandwiches probably. And she's threatened mewith overshoes for a month. Ready now!"

I had a kaleidoscopic view of Mrs. Klopton in the lower hall, holdingout an armful of such traveling impedimenta as she deemed essential,while beside her, Euphemia, the colored housemaid, grinned over awhite-wrapped box.

"Awfu

lly sorry-no time-back Sunday," I panted over my shoulder. Then thedoor closed and the car was moving away.

McKnight bent forward and stared at the facade of the empty house nextdoor as we passed. It was black, staring, mysterious, as empty buildingsare apt to be.

"I'd like to hold a post-mortem on that corpse of a house," he saidthoughtfully. "By George, I've a notion to get out and take a look."

"Somebody after the brass pipes," I scoffed. "House has been empty for ayear."

With one hand on the steering wheel McKnight held out the other for mycigarette case. "Perhaps," he said; "but I don't see what she would wantwith brass pipe."

"A woman!" I laughed outright. "You have been looking too hard at thepicture in the back of your watch, that's all. There's an experimentlike that: if you stare long enough--"

But McKnight was growing sulky: he sat looking rigidly ahead, and hedid not speak again until he brought the Cannonball to a stop at thestation. Even then it was only a perfunctory remark. He went through thegate with me, and with five minutes to spare, we lounged and smokedin the train shed. My mind had slid away from my surroundings and hadwandered to a polo pony that I couldn't afford and intended to buyanyhow. Then McKnight shook off his taciturnity.

"For heaven's sake, don't look so martyred," he burst out; "I knowyou've done all the traveling this summer. I know you're missing a gameto-morrow. But don't be a patient mother; confound it, I have to go toRichmond on Sunday. I--I want to see a girl."

"Oh, don't mind me," I observed politely. "Personally, I wouldn't changeplaces with you. What's her name--North? South?"

"West," he snapped. "Don't try to be funny. And all I have to say,Blakeley, is that if you ever fall in love I hope you make an egregiousass of yourself."

In view of what followed, this came rather close to prophecy.

The trip west was without incident. I played bridge with a furnituredealer from Grand Rapids, a sales agent for a Pittsburg iron firm anda young professor from an eastern college. I won three rubbers out offour, finished what cigarettes McKnight had left me, and went to bedat one o'clock. It was growing cooler, and the rain had ceased. Once,toward morning, I wakened with a start, for no apparent reason, and satbolt upright. I had an uneasy feeling that some one had been looking atme, the same sensation I had experienced earlier in the evening at thewindow. But I could feel the bag with the notes, between me and thewindow, and with my arm thrown over it for security, I lapsed again intoslumber. Later, when I tried to piece together the fragments of thatjourney, I remembered that my coat, which had been folded and placedbeyond my restless tossing, had been rescued in the morning from aheterogeneous jumble of blankets, evening papers and cravat, had beenshaken out with profanity and donned with wrath. At the time, nothingoccurred to me but the necessity of writing to the Pullman Company andasking them if they ever traveled in their own cars. I even formulatedsome of the letter.

"If they are built to scale, why not take a man of ordinary statureas your unit?" I wrote mentally. "I can not fold together like thetraveling cup with which I drink your abominable water."

I was more cheerful after I had had a cup of coffee in the UnionStation. It was too early to attend to business, and I lounged in therestaurant and hid behind the morning papers. As I had expected, theyhad got hold of my visit and its object. On the first page was a staringannouncement that the forged papers in the Bronson case had beenbrought to Pittsburg. Underneath, a telegram from Washington stated thatLawrence Blakeley, of Blakeley and McKnight, had left for Pittsburg thenight before, and that, owing to the approaching trial of the Bronsoncase and the illness of John Gilmore, the Pittsburg millionaire, who wasthe chief witness for the prosecution, it was supposed that the visitwas intimately concerned with the trial.

I looked around apprehensively. There were no reporters yet in sight,and thankful to have escaped notice I paid for my breakfast and left.At the cab-stand I chose the least dilapidated hansom I could find, andgiving the driver the address of the Gilmore residence, in the East end,I got in.

I was just in time. As the cab turned and rolled off, a slim young manin a straw hat separated himself from a little group of men and hurriedtoward us.

"Hey! Wait a minute there!" he called, breaking into a trot.

But the cabby did not hear, or perhaps did not care to. We joggedcomfortably along, to my relief, leaving the young man far behind. Iavoid reporters on principle, having learned long ago that I am an easymark for a clever interviewer.

It was perhaps nine o'clock when I left the station. Our way was alongthe boulevard which hugged the side of one of the city's great hills.Far below, to the left, lay the railroad tracks and the seventy timesseven looming stacks of the mills. The white mist of the river, thegrays and blacks of the smoke blended into a half-revealing haze, dottedhere and there with fire. It was unlovely, tremendous. Whistler mighthave painted it with its pathos, its majesty, but he would have missedwhat made it infinitely suggestive--the rattle and roar of iron on iron,the rumble of wheels, the throbbing beat, against the ears, of fire andheat and brawn welding prosperity.

Something of this I voiced to the grim old millionaire who wasresponsible for at least part of it. He was propped up in bed in hisEast end home, listening to the market reports read by a nurse, and hesmiled a little at my enthusiasm.

"I can't see much beauty in it myself," he said. "But it's our badgeof prosperity. The full dinner pail here means a nose that looks like aflue. Pittsburg without smoke wouldn't be Pittsburg, any more than NewYork without prohibition would be New York. Sit down for a few minutes,Mr. Blakeley. Now, Miss Gardner, Westinghouse Electric."

The nurse resumed her reading in a monotonous voice. She read literallyand without understanding, using initials and abbreviations as theycame. But the shrewd old man followed her easily. Once, however, hestopped her.

"D-o is ditto," he said gently, "not do."

As the nurse droned along, I found myself looking curiously at aphotograph in a silver frame on the bed-side table. It was the pictureof a girl in white, with her hands clasped loosely before her. Againstthe dark background her figure stood out slim and young. Perhaps it wasthe rather grim environment, possibly it was my mood, but although as ageneral thing photographs of young girls make no appeal to me, this onedid. I found my eyes straying back to it. By a little finesse I evenmade out the name written across the corner, "Alison."

Mr. Gilmore lay back among his pillows and listened to the nurse'slistless voice. But he was watching me from under his heavy eyebrows,for when the reading was over, and we were alone, he indicated thepicture with a gesture.

"I keep it there to remind myself that I am an old man," he said. "Thatis my granddaughter, Alison West."

I expressed the customary polite surprise, at which, finding meresponsive, he told me his age with a chuckle of pride. More surprise,this time genuine. From that we went to what he ate for breakfastand did not eat for luncheon, and then to his reserve power, which atsixty-five becomes a matter for thought. And so, in a wide circle, backto where we started, the picture.

"Father was a rascal," John Gilmore said, picking up the frame. "Thehappiest day of my life was when I knew he was safely dead in bed andnot hanged. If the child had looked like him, I--well, she doesn't.She's a Gilmore, every inch. Supposed to look like me."

"Very noticeably," I agreed soberly.

I had produced the notes by that time, and replacing the picture Mr.Gilmore gathered his spectacles from beside it. He went over the fournotes methodically, examining each carefully and putting it down beforehe picked up the next. Then he leaned back and took off his glasses.

"They're not so bad," he said thoughtfully. "Not so bad. But I never sawthem before. That's my unofficial signature. I am inclined to think--"he was speaking partly to himself--"to think that he has got hold ofa letter of mine, probably to Alison. Bronson was a friend of herrapscallion of a father."

I took Mr. Gilmore's deposition and put it into my traveling-bag withthe forg

ed notes. When I saw them again, almost three weeks later, theywere unrecognizable, a mass of charred paper on a copper ashtray. In theinterval other and bigger things had happened: the Bronson forgery casehad shrunk beside the greater and more imminent mystery of the man inlower ten. And Alison West had come into the story and into my life.