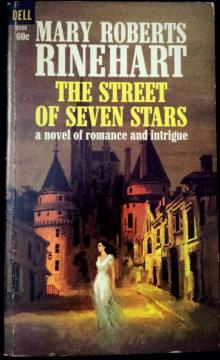

The Street of Seven Stars

Mary Roberts Rinehart

Produced by Michael Delaney

THE STREET OF SEVEN STARS

By Mary Roberts Rinehart

CHAPTER I

The old stucco house sat back in a garden, or what must once have beena garden, when that part of the Austrian city had been a royal gamepreserve. Tradition had it that the Empress Maria Theresa had used thebuilding as a hunting-lodge, and undoubtedly there was something royalin the proportions of the salon. With all the candles lighted in thegreat glass chandelier, and no sidelights, so that the broken panelingwas mercifully obscured by gloom, it was easy to believe that the greatempress herself had sat in one of the tall old chairs and listened toanecdotes of questionable character; even, if tradition may be believed,related not a few herself.

The chandelier was not lighted on this rainy November night. Outsidein the garden the trees creaked and bent before the wind, and theheavy barred gate, left open by the last comer, a piano student namedScatchett and dubbed "Scatch"--the gate slammed to and fro monotonously,giving now and then just enough pause for a hope that it had latcheditself, a hope that was always destroyed by the next gust.

One candle burned in the salon. Originally lighted for the purpose ofenabling Miss Scatchett to locate the score of a Tschaikowsky concerto,it had been moved to the small center table, and had served to givelight if not festivity to the afternoon coffee and cakes. It stillburned, a gnarled and stubby fragment, in its china holder; round it thedisorder of the recent refreshment, three empty cups, a half of asmall cake, a crumpled napkin or two,--there were never enough to goround,--and on the floor the score of the concerto, clearly abandonedfor the things of the flesh.

The room was cold. The long casement windows creaked in time with theslamming of the gate and the candle flickered in response to a draftunder the doors. The concerto flapped and slid along the uneven oldfloor. At the sound a girl in a black dress, who had been huddlednear the tile stove, rose impatiently and picked it up. There was noimpatience, however, in the way she handled the loose sheets. She putthem together carefully, almost tenderly, and placed them on the top ofthe grand piano, anchoring them against the draft with a china dog fromthe stand.

The room was very bare--a long mirror between two of the windows, halfa dozen chairs, a stand or two, and in a corner the grand piano. Therewere no rugs--the bare floor stretched bleakly into dim corners andwas lost. The crystal pendants of the great chandelier looked likestalactites in a cave. The girl touched the piano keys; they were iceunder her fingers.

In a sort of desperation she drew a chair underneath the chandelier, andarmed with a handful of matches proceeded to the unheard-of extravaganceof lighting it, not here and there, but throughout as high as she couldreach, standing perilously on her tiptoes on the chair.

The resulting illumination revealed a number of things: It showed thatthe girl was young and comely and that she had been crying; it revealedthe fact that the coal-pail was empty and the stove almost so; it letthe initiated into the secret that the blackish fluid in the cups hadbeen made with coffee extract that had been made of Heaven knows what;and it revealed in the cavernous corner near the door a number oftrunks. The girl, having lighted all the candles, stood on the chair andlooked at the trunks. She was very young, very tragic, very feminine. Adoor slammed down the hall and she stopped crying instantly. Diving intoone of those receptacles that are a part of the mystery of the sex, sherubbed a chamois skin over her nose and her reddened eyelids.

The situation was a difficult one, but hardly, except to Harmony Wells,a tragedy. Few of us are so constructed that the Suite "Arlesienne"will serve as a luncheon, or a faulty fingering of the Waldweben from"Siegfried" will keep us awake at night. Harmony had lain awake morethan once over some crime against her namesake, had paid penances ofearly rising and two hours of scales before breakfast, working withstiffened fingers in her cold little room where there was no room for astove, and sitting on the edge of the bed in a faded kimono where oncepink butterflies sported in a once blue-silk garden. Then coffee, rolls,and honey, and back again to work, with little Scatchett at the piano inthe salon beyond the partition, wearing a sweater and fingerless glovesand holding a hot-water bottle on her knees. Three rooms beyond, downthe stone hall, the Big Soprano, doing Madama Butterfly in bad German,helped to make an encircling wall of sound in the center of which onemight practice peacefully.

Only the Portier objected. Morning after morning, crawling out at dawnfrom under his featherbed in the lodge below, he opened his door andlistened to Harmony doing penance above; and morning after morning heshook his fist up the stone staircase.

"Gott im Himmel!" he would say to his wife, fumbling with the knot ofhis mustache bandage, "what a people, these Americans! So much noise andno music!"

"And mad!" grumbled his wife. "All the day coal, coal to heat; and atnight the windows open! Karl the milkboy has seen it."

And now the little colony was breaking up. The Big Soprano was goingback to her church, grand opera having found no place for her. Scatchwas returning to be married, her heart full, indeed, of music, but herhead much occupied with the trousseau in her trunks. The Harmar sistershad gone two weeks before, their funds having given out. Indeed, fundswere very low with all of them. The "Bitte zum speisen" of the littleGerman maid often called them to nothing more opulent than a stew ofbeef and carrots.

Not that all had been sordid. The butter had gone for opera tickets, andnever was butter better spent. And there had been gala days--a fruitcakefrom Harmony's mother, a venison steak at Christmas, and once or twiceon birthdays real American ice cream at a fabulous price and worth it.Harmony had bought a suit, too, a marvel of tailoring and cheapness, anda willow plume that would have cost treble its price in New York. Oh,yes, gala days, indeed, to offset the butter and the rainy winter andthe faltering technic and the anxiety about money. For that they allhad always, the old tragedy of the American music student abroad--theexpensive lessons, the delays in getting to the Master himself, thecontention against German greed or Austrian whim. And always back inone's mind the home people, to whom one dares not confess that afternine months of waiting, or a year, one has seen the Master once or notat all.

Or--and one of the Harmar girls had carried back this scar in hersoul--to go back rejected, as one of the unfit, on whom even theundermasters refuse to waste time. That has been, and often. Harmonystood on her chair and looked at the trunks. The Big Soprano was callingdown the hall.

"Scatch," she was shouting briskly, "where is my hairbrush?"

A wail from Scatch from behind a closed door.

"I packed it, Heaven knows where! Do you need it really? Haven't you gota comb?"

"As soon as I get something on I'm coming to shake you. Half the teethare out of my comb. I don't believe you packed it. Look under the bed."

Silence for a moment, while Scatch obeyed for the next moment.

"Here it is," she called joyously. "And here are Harmony's bedroomslippers. Oh, Harry, I found your slippers!" The girl got down off thechair and went to the door.

"Thanks, dear," she said. "I'm coming in a minute."

She went to the mirror, which had reflected the Empress Maria Theresa,and looked at her eyes. They were still red. Perhaps if she opened thewindow the air would brighten them.

Armed with the brush, little Scatchett hurried to the Big Soprano'sroom. She flung the brush on the bed and closed the door. She held hershabby wrapper about her and listened just inside the door. There wereno footsteps, only the banging of the gate in the wind. She turned tothe Big Soprano, heating a curling iron in the flame of a candle, andheld out her hand.

"Look!" she said. "Under my bed! Ten kronen!"

Without a word the Big Soprano put down her curling-iron,

andponderously getting down on her knees, candle in hand, inspected thedusty floor beneath her bed. It revealed nothing but a cigarette, onwhich she pounced. Still squatting, she lighted the cigarette in thecandle flame and sat solemnly puffing it.

"The first for a week," she said. "Pull out the wardrobe, Scatch; theremay be another relic of my prosperous days."

But little Scatchett was not interested in Austrian cigarettes with agovernment monopoly and gilt tips. She was looking at the ten-kronenpiece.

"Where is the other?" she asked in a whisper.

"In my powder-box."

Little Scatchett lifted the china lid and dropped the tiny gold-piece.

"Every little bit," she said flippantly, but still in a whisper, "addedto what she's got, makes just a little bit more."

"Have you thought of a place to leave it for her? If Rosa finds it,it's good-bye. Heaven knows it was hard enough to get together, withoutlosing it now. I'll have to jump overboard and swim ashore at NewYork--I haven't even a dollar for tips."

"New York!" said little Scatchett with her eyes glowing. "If Henry meetsme I know he will--"

"Tut!" The Big Soprano got up cumbrously and stood looking down. "Youand your Henry! Scatchy, child, has it occurred to your maudlin youngmind that money isn't the only thing Harmony is going to need? She'sgoing to be alone--and this is a bad town to be alone in. And she is notlike us. You have your Henry. I'm a beefy person who has a stomach, andI'm thankful for it. But she is different--she's got the thing that youare as well without, the thing that my lack of is sending me back tofight in a church choir instead of grand opera."

Little Scatchett was rather puzzled.

"Temperament?" she asked. It had always been accepted in the littlecolony that Harmony was a real musician, a star in their lesserfirmament.

The Big Soprano sniffed.

"If you like," she said. "Soul is a better word. Only the rich ought tohave souls, Scatchy, dear."

This was over the younger girl's head, and anyhow Harmony was comingdown the hall.

"I thought, under her pillow," she whispered. "She'll find it--"

Harmony came in, to find the Big Soprano heating a curler in the flameof a candle.