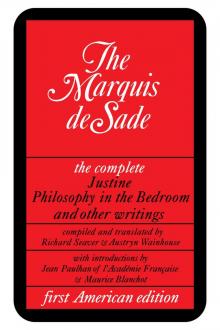

Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writings

Marquis de Sade

Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and other writings

THE MARQUIS DE SADE

COMPILED AND TRANSLATED BY

RICHARD SEAVER & AUSTRYN WAINHOUSE

WITH INTRODUCTIONS BY

JEAN PAULHAN OF L'ACADÉMIE FRANÇAISE & MAURICE BLANCHOT

Copyright © 1965 by Richard Seaver and Austryn Wainhouse

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

Acknowledgments

The essay by Jean Paulhan, “The Marquis de Sade and His Accomplice,” was originally published as a preface to the second edition of Les Infortunes de la Vertu published in 1946 by Les Éditions du Point du Jour, copyright 1946 by Jean Paulhan. The essay was later reprinted, under the title “La Douteuse Justine ou les Revanches de la Vertu,” as an introduction to the 1959 edition of Les Infortunes de la Vertu published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert. It is here reprinted by permission of the author. The essay “Sade” by Maurice Blanchot forms part of that author’s volume entitled Lautréamont et Sade, copyright 1949 by Les Éditions de Minuit, and is here reprinted by permission of the publisher. The editors wish to thank Grove Press, Inc. for permission to include certain information in the Chronology in the form of both entries and notes, taken from The Marquis de Sade, a Definitive Biography, by Gilbert Lely, copyright © 1961 by Elek Books Limited. This work is a one-volume abridgment of the two-volume La Vie du Marquis de Sade by the same author, to which the editors have referred in their Foreword, wherein further acknowledgments have also been made. Finally, the editors wish especially to thank Miss Marilynn Meeker for the meticulous job of editing, and for the number and diversity of her suggestions.

Contents

Foreword

Publisher’s Preface

Part One: Critical & Biographical

The Marquis de Sade and His Accomplice by Jean Paulhan, of l’Académie Française

Sade by Maurice Blanchot

Chronology

Seven Letters (1763-1790)

Note Concerning My Detention (1803)

Last Will and Testament (1806)

Part Two: Two Philosophical Dialogues

Dialogue between a Priest and a Dying Man (1782)

Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795)

Part Three: Two Moral Tales

Eugénie de Franval (1788)

Justine, or Good Conduct Well Chastised (1791)

Bibliography

Notes

My manner of thinking, so you say, cannot be approved. Do you suppose I care? A poor fool indeed is he who adopts a manner of thinking for others! My manner of thinking stems straight from my considered reflections; it holds with my existence, with the way I am made. It is not in my power to alter it; and were it, I’d not do so. This manner of thinking you find fault with is my sole consolation in life; it alleviates all my sufferings in prison, it composes all my pleasures in the world outside, it is dearer to me than life itself. Not my manner of thinking but the manner of thinking of others has been the source of my unhappiness. The reasoning man who scorns the prejudices of simpletons necessarily becomes the enemy of simpletons; he must expect as much, and laugh at the inevitable. A traveler journeys along a fine road. It has been strewn with traps. He falls into one. Do you say it is the traveler’s fault, or that of the scoundrel who lays the traps? If then, as you tell me, they are willing to restore my liberty if I am willing to pay for it by the sacrifice of my principles or my tastes, we may bid one another an eternal adieu, for rather than part with those, I would sacrifice a thousand lives and a thousand liberties, if I had them. These principles and these tastes, I am their fanatic adherent; and fanaticism in me is the product of the persecutions I have endured from my tyrants. The longer they continue their vexations, the deeper they root my principles in my heart, and I openly declare that no one need ever talk to me of liberty if it is offered to me only in return for their destruction.

—THE MARQUIS DE SADE, IN A LETTER TO HIS WIFE

Foreword

That the Marquis de Sade also wrote books is a fact now known to almost everyone who reads. And knowledge of Sade as a writer ordinarily ends there. For of his immense and incomparable literary achievement, and of his capital importance in the history of ideas, hardly a suspicion has been conveyed by occasional collections of anodyne fragments culled from his writings or by more frequent and flagrantly spurious “adaptations.” (Of the two, cheap-paperback pastiche and more tastefully contrived anthology of excerpts, the latter, equally meretricious, is hardly the less dishonest.) To date, this is Sade bibliography in the United States. To date, Sade remains an unknown author.

For this, censorship, Puritan morality, hypocrisy, and lack of cultivation may be blamed, although not very usefully, since Sade sought condemnation. Ultimately, the fault for it is all his own, and the fate of his books is his triumph. Strange? To be and to stay an unknown author, that has always been his status and his destiny, that was the status he coveted, that was the destiny he created for himself, not by accident or unwittingly, but deliberately and out of an uncommon perversity. To write, but to go unread—this has happened to many writers. To write endlessly and under the most unfavorable conditions and as though nothing mattered more than to write, but to write in such a way, at such length, upon such subjects, in such a manner and using such language as to render oneself unapproachable, “unpublishable,” “unknown,” and yet upon succeeding generations to exert the most intense and enduring influence—this, it will be admitted, is rare indeed.

Secrets cannot survive their disclosure; to bare Sade to the public would seem to be rendering him a disservice. Against this “betrayal”—a graver one by far than any accomplished by the obscure tradesmen who from time to time get out a child’s version of Justine—Sade has a defense: it consists in maintaining the reader at a distance, not merely at arm’s length but at a remove one is tempted to call absolute. Or, to put it more simply, in forcing every reader—every so-called reasonable reader—to reject him.

Thus, the present attempt—which is the first to be made in the United States—to provide the basis for a serious understanding of Sade is in a certain sense bound to fail. In this sense: the “reasonable” man (we repeat) can come to no understanding with this exceptional man who rejects everything by which and for which the former lives—laws, beliefs, duties, fears, God, country, family, fellows—everything and the human condition itself, and proposes instead a way of life which is the undoing of common sense and all its works, and which from the point of view of common sense resembles nothing so much as death; and which is, of course, impossible. Such must be the judgment of the “reasonable” man—of him who builds, saves, increases, continues, and thanks to whom the world goes round.

Even so, however firmly he be established in the normality that makes everyday life possible, still more firmly established in him and infinitely more deeply—in the farther reaches of his inalienable self, in his

instincts, his dreams, his incoercible desires—the impossible dwells, a sovereign in hiding. What Sade has to say to us—and what we as normal social beings cannot heed or even hear—already exists within us, like a resonance, a forgotten truth, or like the divine promise whose fulfillment is finally the most solemn concern of our human existence.

Whether or not it is dangerous to read Sade is a question that easily becomes lost in a multitude of others and has never been settled except by those whose arguments are rooted in the conviction that reading leads to trouble. So it does; so it must, for reading leads nowhere but to questions. If books are to be burned, Sade’s certainly must be burned along with the rest. But if, ultimately, freedom has any meaning, any meaning profounder than the facile utterances that fill our speeches and litter the columns of our periodicals, then, we submit, they should not. At any rate, it is not our intention to enter any special plea for Sade. Nor to apologize for one of our civilization’s treasures. Disinterred or left underground, Sade neither gains nor loses. While for us . . . the worst poverty may be said to consist in the ignorance of one’s riches.

* * *

Great writing needs no justification, no complex exegesis: it is its own defense. Still, the special nature of Sade’s work, the legend attached to his name, and the unusual length of time intervening between the writing and the present publication seemed to call for some introduction, both critical and biographical. Thus, Part One of the present volume aims at situating Sade in his times and among his familiars. For the brief biography in the form of a Chronology, the editors have relied primarily upon, and are indebted to, Maurice Heine’s outline for a projected Life contained in Volume I of his Œuvres choisies et Pages Magistrales du Marquis de Sade. We also owe a particular debt to Gilbert Lely, Heine’s close friend and heir to the great scholar’s papers. The extent of both their contributions to the establishment of a valid Sade biography, and to a fuller understanding of both the man and his work, is detailed elsewhere.

Sade’s letters are particularly revealing. We have included seven, ranging over an almost thirty-year period from the year of his marriage when he was twenty-three to the time of his release from the Monarchy’s dungeons by the Revolutionary government, when he was over fifty. Letter I is from an unpublished manuscript, and is cited in Volume I of Lely’s biography; Letters II, III, IV, and V are from L’Aigle Mademoiselle. . .;1 Letters VI and VII are from Paul Bourdin’s Correspondance.

We have included two exploratory essays on Sade. The first, by Jean Paulhan, was written in 1946 as the Preface for a second edition of Les Infortunes de la Vertu published that year. The second, by Maurice Blanchot, forms part of that author’s volume entitled Lautréamont et Sade which was published by Les Éditions de Minuit in 1949. They form part of a growing body of perceptive Sade criticism which has developed over the past two or three decades.

The “Note Concerning My Detention” was first published in Cahiers personnels (1803–1804). Sade’s “Last Will and Testament” has only recently been published in its entirety in French,2 and is here offered in English for the first time.

If, through the material in Part One, we have tried to situate Sade, we have not attempted to conceal the singularity of his tastes or in any wise to depict him other than he was. He was a voluptuary, a libertine—let it not be forgotten that the latter term derives from the Latin liber: “free”—an exceptional man of exceptional penchants, passions, and ideas. But a monster? In his famous grande lettre to Madame de Sade, dated February 20, 1781, and written while he was a prisoner in the Bastille, Sade declares:

I am a libertine, but I am neither a criminal nor a murderer [italics Sade’s], and since I am compelled to set my apology next to my vindication, I shall therefore say that it might well be possible that those who condemn me as unjustly as I have been might themselves be unable to offset their infamies by good works as clearly established as those I can contrast to my errors. I am a libertine, but three families residing in your area have for five years lived off my charity, and I have saved them from the farthest depths of poverty. I am a libertine, but I have saved a deserter from death, a deserter abandoned by his entire regiment and by his colonel. I am a libertine, but at Evry, with your whole family looking on, I saved a child—at the risk of my life—who was on the verge of being crushed beneath the wheels of a runaway horse-drawn cart, by snatching the child from beneath it. I am a libertine, but I have never compromised my wife’s health. Nor have I been guilty of the other kinds of libertinage so often fatal to children’s fortunes: have I ruined them by gambling or by other expenses that might have deprived them of, or even by one day foreshortened, their inheritance? Have I managed my own fortune badly, as long as I had a say in the matter? In a word, did I in my youth herald a heart capable of the atrocities of which I today stand accused?. . . How therefore do you presume that, from so innocent a childhood and youth, I have suddenly arrived at the ultimate of premeditated horror? no, you do not believe it. And you who today tyrannize me so cruelly, you do not believe it either: your vengeance has beguiled your mind, you have proceeded blindly to tyrannize, but your heart knows mine, it judges it more fairly, and it knows full well it is innocent.3

It was as a libertine that Sade first ran afoul of the authorities. It was society—a society Sade termed, not unjustly, as “thoroughly corrupted”—that feared a man so free it condemned him for half his adult life, and in so doing made of him a writer. If there is a disparity between the life and the writings, the society that immured him is to blame. With his usual perception about himself, Sade once noted in a letter to his wife that, had the authorities any insight, they would not have locked him up to plot and daydream and make philosophical disquisitions as wild and vengeful and absolute as any ever formulated; they would have set him free and surrounded him with a harem on whom to feast. But societies do not cater to strange tastes; they condemn them. Thus Sade became a writer.

In presenting Sade the writer, in Parts Two and Three of the present volume, we made a number of fundamental decisions at the outset. We first decided to include nothing but complete works. Otherwise, in our opinion, the endeavor was pointless. Further, as Sade was a writer both of works he acknowledged and works he disclaimed (and who is to say which of the two types most fairly represents him?) it seemed essential to offer examples of both sorts. Without which, again, the endeavor was pointless—and hypocritical. Finally, in making our selections we have obviously chosen works we believe represent him fairly and are among his best.

Part Two consists of two of his philosophical dialogues. The first, Dialogue between a Priest and a Dying Man, written in 1782 and until recently thought to be Sade’s earliest literary effort, was not published until 1926. The present translation is from the original edition. The second, Philosophy in the Bedroom, was first published in 1795, not under Sade’s name, or only by inference: it appeared simply as “by the Author of Justine.” It is a major work, represents a not unfair example of the clandestine writings, and contains the justly famous philosophical-political tract, “Yet Another Effort, Frenchmen, If You Would Become Republicans,” which is as good, as reasonably concise a summation of his viewpoint as we have. It is a work of amazing vigor, imbued throughout with Sade’s dark—but not bitter—humor, and creates a memorable cast of Sadean characters. Although Lely deems it the “least cruel” of his clandestine writings, Philosophy will reveal what all the clamor is about. The translation is from the 1952 edition published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert.

Two of Sade’s moral tales make up Part Three. Eugénie de Franval, which dates from 1788, is generally judged to be one of the two or three best novella-length works which Sade wrote and is, in the opinion of many, a minor masterpiece of eighteenth-century French literature. The translation is from the 1959 edition of Les Crimes de l’Amour published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert. Finally, the inclusion of Justine, here presented for the first time in its complete form, was mandatory. It is Sade’s most famous novel, although there a

re several more infamous. It is the work, too, which bridges the gap between the avowed and the clandestine, and is thus of special interest. For if it is true that, consciously or unconsciously, Sade was seeking condemnation, with Justine he was seeing to what lengths he could go and remain read. The translation is from the 1950 edition published by Le Soleil Noir, which contains a preface by Georges Bataille.

Each of the four works presented is directly preceded by a historical-bibliographical note which will, we trust, help situate it.

It is our hope that this volume will contribute to a better understanding of a man who has too long been steeped in shadow. If it does, it will be but slight retribution for the countless ignominies to which Sade was subjected during his long, tormented, and incredibly patient life, and during the century and a half since his death.

In his will, Sade ordered that acorns be strewn over his grave, “in order that, the spot become green again, and the copse grown back thick over it, the traces of my grave may disappear from the face of the earth, as I trust the memory of me shall fade out of the minds of men. . . .” Of all Sade’s prophecies small or splendid, this one, about himself, seems the least likely to come true.

R.S., A.W.

Publisher’s Preface

Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade, better known to history as the Marquis de Sade, has rarely, if ever, had a fair hearing. A good portion of his adult life was spent in the prisons and dungeons and asylums of the sundry French governments under which he lived—Monarchy, Republic, Consulate, and Empire. During his lifetime, or shortly after his death, most of his writings were destroyed either by acts of God or by acts of willful malice, not only by Sade’s enemies but also by his friends and even his family—which was chiefly concerned with erasing his dark stain from its honored escutcheon. As recently as World War II, some of Sade’s personal notebooks and correspondence, which had miraculously been preserved for over a century and a quarter, fell into the hands of the pillaging Germans and were lost, rendered unintelligible by exposure to the elements, or simply destroyed. Of Sade’s creative work—excepting his letters and diaries—less than one fourth of what he wrote has come down to us.