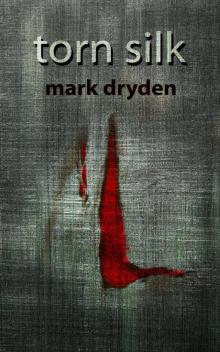

Torn Silk

Mark Dryden

Torn Silk

Title Page

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

TORN SILK

BY

MARK DRYDEN

Published at Smashwords

Copyright 2016

"How small, of all that human hearts endure,

That part which laws or kings can cause or cure.

Still to ourselves in every place consign'd,

Our own felicity we make or find”

- Samuel Johnson

CHAPTER ONE

Early Friday morning. I strolled into the room of Terry Riley, Senior Counsel, and found him taking lusty practice swings with a golf club. He belted an imaginary ball far into the distance.

I said: "I think that one went into the rough."

He turned and smiled. "Morning Ben. Play golf?"

"Only when forced at gun-point."

He thought I was joking. "Hah, hah. Can't stop slicing my tee-shots. Bloody annoying."

I sat in an armchair and watched him swing the golf club a few more times. His artificial and larger-than-life personality made him seem indestructible, like a Styrofoam cup. I certainly had no idea he would soon be murdered in a most grisly and violent fashion.

Terry and I both belonged to Thomas Erskine Chambers, a floor of thirty barristers who shared expenses, shared work, shared gossip and shared problems if anyone would listen. We were both personal injuries barristers. So we appeared in court for anyone suing or being sued over a motor vehicle accident, botched medical operation, shopping centre fall, food poisoning or the like. Most hearings focused on two basic questions: who caused the damage and how much was it worth? Fine points of law rarely intruded. In Court we wore the same garb that Charles Dickens observed when he was a court reporter. It was a golden life if you could make a buck.

The Bar Association had appointed Terry as a Senior Counsel, which allowed him to wear a silk robe and over-charge with impunity. He was sixty-one and looked hand-made for the role; he was tall and broad-shouldered with a helmet of grey hair, high forehead, firm lips and decisive chin. In court, he stood like a lord on his battlements and spoke like he was describing the first dawn. Gravitas and self-confidence should have been separate items on his bills.

However, the contents of his fine-looking head weren't much to write home about. When making submissions to a judge, he often seized upon an untenable argument and brandished it aloft like a burning torch as he charged into a forensic cul-de-sac. Judges often had to make him shut up so they could explain the real reason his client was going to win - and even then he sometimes didn't get it. When cross-examining, he was like a blindfolded man trying to hit a piñata.

Nor was he a great worker. There is a hoary adage that old barristers are like old boxers: it's not the fighting that gets too hard, it's the training. Terry was a case in point. He'd never prepared much for hearings. Now, he prepared even less.

Yet, despite his shortcomings, he'd had a very successful career. Clients usually assess barristers on the basis of their looks and confidence, and Terry had both in abundance. Further, when he lost, he was adept at blaming a witness, the judge or his opponent, while looking slightly embarrassed to be part of such a pathetic and unjust system. I'd seen clients who lost cases start feeling sorry for him.

In an hour or so, we would appear - as silk and junior - for a plaintiff in a hearing in the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Having Terry lead me was both good and bad. He was usually pleasant to deal with and amenable to advice. However, when listening to him in court, I often wanted to wrestle him to the ground and stuff his wig into his mouth. I also felt a little uncomfortable spending all day with him because I'd been sleeping with his wife for the last five years, without getting caught. I felt guilty about that and feared I might make a slip that betray me.

Terry took a final swipe with his driver, shoved it into a gargantuan golf bag and dropped into the chair behind his desk. "Have we been allocated a judge yet?"

"Yes. The registry called my secretary a few minutes ago: we've got a ten o'clock start before Dick Sloan."

Terry smiled. "Dick? That's good news."

His reaction surprised me. He was a good pal of Sloan and would be treated with courtesy. But Sloan rarely gave verdicts in favour of plaintiffs and, when he did, usually awarded measly damages.

I said: "You're kidding, right? That black-hearted bastard eats plaintiffs for breakfast."

Terry smiled. "He's not that bad; he'll give us a fair hearing."

"If he does, you can cut off my legs and call me Shorty."

Terry's phone rang. He picked up the receiver and listened briefly. "OK, send him in."

He put down the receiver. "Bob Meredith's here."

About ten seconds later our instructing solicitor, Bob Meredith, steamed into the room carrying a leather brief-case and trilby hat. Almost sixty, he was bald and stocky, and wore an expensive suit and chunky Rolex. Everything about him said that life was a transaction. He owned Meredith & Co, a firm that employed half-a-dozen solicitors to run personal injuries actions on a no-win/no-fee basis. That was the basis on which Terry and I had taken the present brief. Meredith was earning enough to own a mansion in Vaucluse and a big yacht called Feenomenal. The name said it all.

Meredith had briefed Terry for a long time, mainly because Terry did what Meredith told him to do: if Meredith wanted to fight hard, Terry slugged it out in court; if Meredith wanted to settle, Terry water-boarded the client to take the money on offer. Further, Terry never complained when Meredith's firm did its usual slack job of preparing a brief. Indeed, he hardly seemed to notice.

However, Meredith and I had never got on well. I didn't like his mercantile approach and distain for clients, and he knew that. So he only briefed me when Terry demanded that I be his junior, as Terry had in this case.

We all exchanged greetings and Meredith said: "We got a start?"

I said: "Yes, the registry called: we're before Dick Sloan at ten o'clock."

To my surprise, Meredith also smiled. "Good".

"Really?"

"Yes."

"He's a miserable turd."

Meredith raised his eyebrows, scratched his broken nose - he liked to tell clients it was busted during a fist-fight with an opposing solicitor - and said: "Oh, he's not too bad. Bark's worse than his bite."

What pills were these guys taking?

Terry looked at Meredith. "Client here?"

"Yes, outside, with his parents."

"Good. Wheel him in."

Terry had met our client only once, several months ago. So, as Meredith strolled off, he glanced down at the coversheet of his brief to confirm his name.

The solicitor returned with our client, Mick Arnold, limping behind him. Mick was in his early twenties, with a ginger mullet, narrow freckly face and jug ears pierced with several gold

earrings. He looked like an un-cunning fox. Meredith must have asked him to dress well, because he wore a clean and well-pressed Wallabies jersey. Peeking just above the collar was the tattooed head of a snake. He looked mildly pleased that the world was finally paying attention to him.

He had brought a claim for assault and battery. Eight months ago, on a Saturday night, in the Royal George Hotel in Bondi, he and his girlfriend sat in the upstairs bar and got seriously hammered. Their darker selves emerged and, after a fierce argument, she stormed off.

Mick should have gone too. But he kept drinking and propositioned a woman sitting next to him. She was not impressed. Nor was her boyfriend. The two men started pushing and shoving. Two hulking bouncers, Vincent Taggart and Desmond Fuolau, arrived and asked Mick to leave.

There were two versions of what followed.

According to Mick, the bouncers frogmarched him to the top of the stairs and tossed him down them. He landed near the bottom, hit his head and blacked out.

Later, at St Vincent's Hospital, x-rays revealed a couple of broken vertebrae. But the orthopaedic surgeon predicted that, in a few months, he'd be right as rain. However, according to Mick, a few months later he still had a lame left leg, three paralysed right fingers and almost insufferable back pain. He went on a disability pension and visited Bob Meredith, who promised to recover huge damages.

Meredith & Co filed a claim in the Supreme Court that alleged assault and battery against the two bouncers and the company that owned the pub. It sought more than a million dollars for Mick's pain-and-suffering, future economic loss and medical expenses.

The bouncers denied touching Mick. According to them, they persuaded him to leave the pub under his own steam but, at the top of the stairs, he tripped and fell. Their insurance company stepped in to defend the claim.

During my fifteen years as a personal injuries barrister, I'd represented plaintiffs who were the salt of the earth and bore their suffering with immense fortitude. I'd also represented liars and cheats trying to bilk the system. Unfortunately, it was hard to distinguish between the two. Honest plaintiffs could seem shifty and crooks could lie with grace and charm. But as soon as I clapped my eyes on Mick, I smelt bullshit and suspected any sensible judge would do the same.

Mick sat tentatively in an armchair and Terry perched on a corner of his desk, looking avuncular. "How're you feeling?"

Mick's Adam's apple ducked and weaved. "A bit nervous, I guess. I'll be OK."

"Well, you'll be pleased to know the hearing will start at ten o'clock before Justice Richard Sloan."

"Good. What're me chances?"

Terry shrugged. "Hard to say. As you know, both sides have different versions of what happened. It all depends on who the judge believes."

"Any chance we can settle?"

Terry glanced at Bob Meredith. "So far they haven't offered anything, right?"

Meredith said: "Correct. They're playing hardball."

Mick looked annoyed. "I want a million, because I can't work no more. Those bastards have got to pay, big time."

"Fair enough. Just remember this: if we run this case and you lose, the judge will make a big costs order against you and the defendants will end up owning your living room."

"I don't own no living room; I've got nothing except a shitty car."

Terry shrugged. "I guess that's an advantage. Anyway, let's not get ahead of ourselves. I'll talk to the barrister for the defendants and see if they want to settle. If not, we'll obviously have to fight."

Mick said: "Who's their barrister? He any good?"

Terry glanced at me. "Who've they got?"

"Don't know. Until recently, it was Bert Truman. But he told me yesterday that he's jammed. Don't know who's replaced him."

Meredith interrupted. "I spoke to their solicitor this morning. They've briefed Bill Anderson."

Terry frowned. "My goodness, Wild Bill. This will be interesting."

Mick said: "Really? What's he like?"

For once, Terry looked flustered. "He's, umm, very aggressive. So when you give evidence, stay cool and keep your nerve."

Mick looked alarmed. "OK. Is that why they call him Wild Bill, because he's so aggro?"

"Yes. But don't worry, I can handle him."

I doubted that. I really did.

Terry put on his wig and gown. "Right, let's go." He made a sweeping gesture with his arm, like John Wayne starting a cattle drive, and headed for the door with the rest of us moseying along behind.

CHAPTER TWO

Phillip Street ran through the heart of Sydney's legal precinct. Barristers' chambers occupied ugly buildings on each side, and the Supreme Court was housed in a forbidding concrete tower at one end. Every morning, desperate litigants and their barristers trekked into that Fortress of Doom searching for justice. Instead, they encountered overworked judges who had to cut their way through thickets of lies to reach elusive truths. Usually, the only victors were the lawyers.

Thomas Erskine Chambers occupied the fifth floor of a drab office block opposite the Supreme Court tower. Just before ten o'clock, Terry led our small party across the road to join several gloomy souls trudging into it. Their clients looked even unhappier. The tower scowled down at everyone.

Inside, we passed through a metal-detector and caught a lift up to the 13th floor, which had eight courtrooms. About thirty lawyers and their clients milled about in the hallway, anxiously waiting for the courtroom doors to open. There were also several litigants-in-person: bug-eyed crusaders with festering grievances whose court documents were stuffed into back-packs and shopping trolleys. They were assured of Victory because they marched under the banner of Truth.

Terry, Meredith and I stood outside Court 13A, exchanging legal gossip, while Mick and his parents, who shared his hard features and beady eyes, sat on a nearby foam bench.

Plaintiffs in personal injuries actions often attract hangers-on, hungrily eyeing the potential spoils. Maybe his parents hoped to gain a new house, car or boat; or maybe, as usual, I was being unfair.

Lift doors opened and Bill Anderson SC surged out, hands tucked inside his gown to make it billow dramatically. Trailing him, like feudal retainers, were his barrister son, Bill Anderson Jnr, and a gangly solicitor pushing a trolley bulging with lever-arch files. Strutting behind them were two heavily muscled young men with slick hair wearing shiny double-breasted suits: presumably Vincent Taggart and Desmond Fuolau.

Though in his mid-sixties, Wild Bill Anderson was still tall and robust, with a reddish square face and choleric eyes. In court, he bristled with menace, barking at judges, opponents, witnesses, his own solicitor and sometimes even his own client. I once saw him tear strips off a client for a poor performance in the witness box. In a way, I admired him, because he never short-changed clients on vigour and aggression. Indeed, he was so mercurial that he could easily win an unwinnable case, and lose an unlosable one.

His son was very different. "Mild Bill" was round-faced, round-waisted and quiet-spoken. He'd been at the Bar for ten years and, though quite bright, still lingered in his father's shadow.

Wild Bill shoved the door of Court 13A and realised it was locked. He looked ready to break it down, then grunted and looked around peevishly.

Terry smiled nervously and shows his palms. "Hi, Bill. We'll be crossing swords again."

Another grunt. "You're for the plaintiff?"

"Yes. Do you want to chat?"

Wild Bill frowned. "What about?"

"Well, is this hearing really necessary?"

Wild Bill raised bushy eyebrows. "What do you mean?"

"Maybe we can, umm, settle it?"

Terry's overture made us look weak. He should have let Wild Bill make the first move, if he was interested.

Another frown. "Depends."

"On what?"

"Whether your client's prepared to walk away with nothing."

"You're not going to offer anything?"

"Correct."

Terry looked anno

yed. "Nothing at all?"

A nasty smile. "That's right: not a cent, not a zac, not a brass razoo. However, because I'm feeling unusually generous, he can walk away without paying our costs. I'm afraid that's the best I can do."

Wild Bill's position was entirely understandable. Even if the insurer was inclined to offer some money, why offer it now? Our client had to get into the witness box first. Why not kick him around for a while and see how he fared?

Terry frowned. "You must be kidding. My client's got a good claim."

"Rubbish, it's hopeless."

"Really? Why're you so confident?"

"Why? Because Dick Sloan hates plaintiffs and will hate your client."

"You're wrong there. He's not as anti-plaintiff as people say."

Wild Bill smirked. "We'll see, won't we?"

"My client won't walk way. He'll bat on."

A hollowed-out smile. "That's good news. See you in court."

On cue, a Court Officer opened the doors of Court 13A and Wild Bill strode between them, minions in tow.

Terry turned towards me. "Jesus, he seems bloody confident. Have we missed something?"

"Don't think so."

"Maybe they've got some film?"

Plaintiff barristers live in fear that a private eye has secretly filmed their client in rude good health. The film usually comes to light during cross-examination and hits like a torpedo below the waterline.

We both glanced at Meredith, who shrugged. "I told him he might be filmed. But he's dumb as dog-shit; maybe he didn't listen."

I was alert but not alarmed - yet. Wild Bill always put on an act. Only time would tell if it was more than bluster.

Terry shrugged and sighed. "Oh, well, looks like we'll have to earn our money. Let's get this show on the road." He adjusted his wig and strolled into the courtroom.

On the stroke of ten o'clock, the Court Officer called for silence. A hidden hand rapped three times on the door behind the bench. As everybody rose, the door swung open and Justice Richard Sloan appeared. He was in his early sixties, tall and lean, with chiselled features, grey eyes and thin lips; he was bright and arrogant, and had a heart drained of pity. At the Bar, he always represented defendant insurance companies. When he became a judge, nothing really changed. Battlers and underdogs got no special favours in his court.