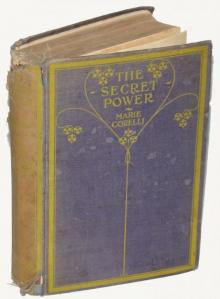

The Secret Power

Marie Corelli

Produced by Charles Franks and the Online DistributedProofreading Team. HTML version by Al Haines.

THE SECRET POWER

BY

MARIE CORELLI

AUTHOR OF

"God's Good Man" "The Master Christian" "Innocent," "The Treasure of Heaven," etc.

JTABLE 5 26 1

THE SECRET POWER

CHAPTER I

A cloud floated slowly above the mountain peak. Vast, fleecy and whiteas the crested foam of a sea-wave, it sailed through the sky with adivine air of majesty, seeming almost to express a consciousness of itsown grandeur. Over a spacious tract of Southern California it extendedits snowy canopy, moving from the distant Pacific Ocean across theheights of the Sierra Madre, now and then catching fire at its extremeedge from the sinking sun, which burned like a red brand flung on theroof of a roughly built hut situated on the side of a sloping hollow inone of the smaller hills. The door of the hut stood open; there were acouple of benches on the burnt grass outside, one serving as a table,the other as a chair. Papers and books were neatly piled on thetable,--and on the chair, if chair it might be called, a man satreading. His appearance was not prepossessing at a first glance, thoughhis actual features could hardly be seen, so concealed were they by aheavy growth of beard. In the way of clothing he had little to troublehim. Loose woollen trousers, a white shirt, and a leathern belt to keepthe two garments in place, formed his complete outfit, finished off bywide canvas shoes. A thatch of dark hair, thick and ill combed,apparently served all his need of head covering, and he seemedunconscious of, or else indifferent to, the hot glare of the summer skywhich was hardly tempered by the long shadow of the floating cloud. Atsome moments he was absorbed in reading,--at others in writing. Closewithin his reach was a small note-book in which from time to time hejotted down certain numerals and made rapid calculations, frowningimpatiently as though the very act of writing was too slow for thespeed of his thought. There was a wonderful silence everywhere,--asilence such as can hardly be comprehended by anyone who has nevervisited wide-spreading country, over-canopied by large stretches ofopen sky, and barricaded from the further world by mountain rangeswhich are like huge walls built by a race of Titans. The dwellers insuch regions are few--there is no traffic save the coming and going ofoccasional pack-mules across the hill tracks--no sign of moderncivilisation. Among such deep and solemn solitudes the sight of aliving human being is strange and incongruous, yet the man seatedoutside his hut had an air of ease and satisfied proprietorship notalways found with wealthy owners of mansions and park-lands. He was sothoroughly engrossed in his books and papers that he hardly saw, andcertainly did not hear, the approach of a woman who came climbingwearily up the edge of the sloping hill against which his cabinpresented itself to the view as a sort of fitment, and advanced towardshim carrying a tin pail full of milk. This she set down within a yardor so of him, and then, straightening her back, she rested her hands onher hips and drew a long breath. For a minute or two he took no noticeof her. She waited. She was a big handsome creature, sun-browned andblack-haired, with flashing dark eyes lit by a spark that was notoriginally caught from heaven. Presently, becoming conscious of herpresence, he threw his book aside and looked up.

"Well! So you've come after all! Yesterday you said you wouldn't."

She shrugged her shoulders.

"I do not wish you to starve."

"Very kind of you! But nothing can starve me."

"If you had no food--"

"I should find some"--he said--"Yes!--I should find some,--somewhere! Iwant very little."

He rose, stretching his arms lazily above his head,--then, stooping, helifted the pail of milk and carried it into his cabin. Disappearing fora moment, he returned, bringing back the pail empty.

"I have enough for two days now," he said--"and longer. What youbrought me at the beginning of the week has turned beautifully sour,--a'lovely curd' as our cook at home used to say--, and with that 'lovelycurd' and plenty of fruit I'm living in luxury." Here he felt in hispockets and took out a handful of coins. "That's right, isn't it?"

She counted them over as he gave them to her--bit one with her strongwhite teeth and nodded.

"You don't pay ME"--she said, emphatically--"It's the Plaza you pay."

"How many times will you remind me of that!" he replied, with alaugh--"Of course I know I don't pay YOU! Of course I know I pay thePlaza!--that amazing hotel and 'sanatorium' with a tropical garden andno comfort--"

"It is more comfortable than this"--she said, with a disparaging glanceat his log dwelling.

"How do YOU know?" and he laughed again--"What have YOU everexperienced in the line of hotels? You are employed at the Plaza tofetch and carry;--to wait on the wretched invalids who come toCalifornia for a 'cure' of diseases incurable--"

"YOU are not an invalid!" she said with a slight accent of contempt.

"No! I only pretend to be!"

"Why do you pretend?"

"Oh, Manella! What a question! Why do we all pretend?--all!--everyhuman being from the child to the dotard! Simply because we dare notface the truth! For example, consider the sun! It is a furnace withflames five thousand miles high, but we 'pretend' it is our beautifulorb of day! We must pretend! If we didn't we should go mad!"

Manella knitted her black brows perplexedly.

"I do not understand you"--she said--"Why do you talk nonsense aboutthe sun? I suppose you ARE ill after all,--you have an illness of thehead."

He nodded with mock solemnity.

"That's it! You're a wise woman, Manella! That's why I'm here. Nottubercles on the lungs,--tubercles on the brain! Oh, those tubercles!They could never stand the Plaza!--the gaiety, the brilliancy--the--theall-too dazzling social round!..." he paused, and a gleam of even whiteteeth under his dark moustache gave the suggestion of a smile--"That'swhy I stay up here."

"You make fun of the Plaza"--said Manella, biting her lipsvexedly--"And of me, too. I am nothing to you!"

"Absolutely nothing, dear! But why should you be any thing?"

A warm flush turned her sunburnt skin to a deeper tinge.

"Men are often fond of women"--she said.

"Often? Oh, more than often! Too often! But what does that matter?"

She twisted the ends of her rose-coloured neckerchief nervously withone hand.

"You are a man"--she replied, curtly--"You should have a woman."

He laughed--a deep, mellow, hearty laugh of pleasure.

"Should I? You really think so? Wonderful Manella? Come here!--comequite close to me!"

She obeyed, moving with the soft tread of a forest animal, and, face toface with him, looked up. He smiled kindly into her dark fierce eyes,and noted with artistic approval the unspoiled beauty of natural linesin her form, and the proud poise of her handsome head on her fullthroat and splendid shoulders.

"You are very good-looking, Manella"--he then remarked, lazily--"Quitethe model for a Juno. Be satisfied with yourself. You should havescores of lovers!"

She stamped her foot suddenly and impatiently.

"I have none!" she said--"And you know it! But you do not care!"

He shook a reproachful forefinger at her.

"Manella, Manella, you are naughty! Temper, temper! Of course I do notcare! Be reasonable! Why should I?"

She pressed both hands tightly against her bosom, seeking to controlher quick, excited breathing.

"Why should you? I do not know! But _I_ care! I would be your woman! Iwould be your slave! I would wait upon you and serve you faithfully! Iwould obey your every wish. I am a good servant,--I can cook and sewand wash and sweep--I can do everything in a house and you should haveno trouble. You should write and read all day,--I would not speak aword to disturb you. I would guard you li

ke a dog that loves hismaster!"

He listened, with a strange look in his eyes,--a look of wonder andsomething of compassion. There was a pause. The silence of the hillswas, or seemed more intense and impressive--the great white cloud stillspread itself in large leisure along the miles of slowly darkening sky.Presently he spoke. "And what wages, Manella? What wages should I haveto pay for such a servant?--such a dog?"

Her head drooped, she avoided his steady, searching gaze.

"What wages, Manella? None, you would say, except--love! You tell meyou would be my woman,--and I know you mean it. You would be myslave--you mean that, too. But you would want me to love you! Manella,there is no such thing as love!--not in this world! There is animalattraction,--the magnetism of the male for the female, the female forthe male,--the magnetism that pulls the opposite sexes together inorder to keep this planet supplied with an ever new crop of fools,--butlove! No, Manella! There is no such thing!"

Here he gently took her two hands away from their tightly foldedposition on her bosom and held them in his own.

"No such thing, my dear!" he went on, speaking softly and soothingly,as though to a child--"Except in the dreams of poets, andyou--fortunately!--know nothing about poetry! The wild animal in you isattracted to the tame, ruminating animal in me,--and you would be mywoman, though I would not be your man. I quite believe that it is thenatural instinct of the female to select her mate,--but, though therule may hold good in the forest world, it doesn't always work amongthe human herd. Man considers that he has the right of selection--quitea mistake of his I'm sure, for he has no real sense of beauty orfitness, and generally selects most vilely. All the same he is anobstinate brute, and sticks to his brutish ideas as a snail sticks toits shell. _I_ am an obstinate brute!--I am absolutely convinced that Ihave the right to choose my own woman, if I want one--which Idon't,--or if ever I do want one--which I never shall!"

She drew her hands quickly from his grasp. There were tears in hersplendid dark eyes.

"You talk, you talk!" she said, with a kind of sob in her voice--"It isall talk with you--talk which I cannot understand! I don't WANT tounderstand!--I am only a poor, ignorant girl. I cannot talk--but I canlove! Ah yes, I can love! You say there is no such thing as love! Whatis it then, when one prays every night and morning for a man?--when onewould work one's fingers to the bone for him?--when one would die tokeep him from sickness and harm? What do you call it?"

He smiled.

"Self-delusion, Manella! The beautiful self-delusion of everynature-bred woman when her fancy is attracted by a particular sort ofman. She makes an ideal of him in her mind and imagines him to be agod, when he is nothing but a devil!"

Something sinister and cruel in his look startled her,--she made thesign of the cross on her bosom.

"A devil?" she murmured--"a devil--?"

"Ah, now you are frightened!" he said, with a flash of amusement in hiseyes--"You are a good Catholic, and you believe in devils. So you makethe sign of the cross as a protection. That's right! That's the way todefend yourself from my evil influence! Wise Manella!"

The light mockery of his tone roused her pride,--that pride which hadbeen suppressed in her by the force of a passionate emotion she couldnot restrain. She lifted her head and regarded him with an air ofsorrow and scorn.

"After all, I think you must be a wicked man!" she said--"You have noheart! You are not worthy to be loved!"

"Quite true, Manella! You've hit the bull's eye in the very middlethree times! I am a wicked man,--I have no heart,--I'm not worthy to beloved. No I'm not. I should find it a bore!"

"Bore?" she echoed--"What is that?"

"What is that? It is itself, Manella! 'Bore' is just 'bore.' It meanstiredness--worn-out-ness--a state in which you wish yourself in a hotbath or a cold one, so that nobody can come near you. To be 'loved'would finish me off in a month!"

Her big eyes opened more widely than their wont in piteous perplexity.

"But how?" she asked.

"How? Why, just as you have put it,--to be prayed for night andmorning,--to be worked for and waited on till fingers turned tobones,--to be guarded from sickness and harm,--heavens!--think of it!No more adventures in life,--no more freedom!--just love, love, love,which would not be love at all but the chains of a miserable wretch inprison!"

She flushed an angry crimson.

"Who is it that would chain you?" she demanded, "Not I! You could do asyou liked with me--you know it!--and when you go away from this place,you could leave me and forget me,--I should never trouble you or remindyou that I lived!! I should have had my happiness,--enough for my day!"

The pathos in her voice moved him though he was not easily moved. On asudden impulse he put an arm about her, drew her to him and kissed her.She trembled at his caress, while he smiled at her emotion.

"A kiss is nothing, Manella!" he said--"We kiss children as I kiss you!You are a child,--a child-woman. Physically you are a Juno,--mentallyyou are an infant! By and by you will grow up,--and you will be glad Idid no more than kiss you! It's getting late,--you must go home."

He released her and put her gently away from him. Then, as he saw hereyes still uplifted questioningly to his face, he laughed.

"Upon my word!" he exclaimed--"I am making a nice fool of myself!Actually wasting time on a woman. Go home, Manella, go home! If you arewise you won't stop here another minute! See now! You are full ofcuriosity--all women are! You want to know why I stay up here in thishill cabin by myself instead of staying at the 'Plaza.' You think I'm arich Englishman. I'm not. No Englishman is ever rich,--not up to hisown desires. He wants the earth and all that therein is--does theEnglishman, and of course he can't have it. He rather grudges Americaher large slice of rich plum-pudding territory, forgetting that hecould have had it himself for the price of tea. But I don't grudgeanybody anything--America is welcome to the whole bulk as far as I'mconcerned--Britain ditto,--let them both eat and be filled. All _I_want is to be left alone. Do you hear that, Manella? To be left alone!Particularly by women. That's one reason why I came here. This cabin issupposed to be a sort of tuberculosis 'shelter,' where a patient inhopeless condition comes with a special nurse to die. I don't want anurse, and I'm not going to die. Tubercles don't touch me--they don'tflourish on my soil. So this solitude just suits me. If I were at the'Plaza' I should have to meet a lot of women--"

"No, you wouldn't," interrupted Manella, suddenly and sharply--"onlyone woman."

"Only one? You?"

She sighed, and moved impatiently.

"Oh, no! Not me. A stranger."

He looked at her with a touch of inquisitiveness.

"An invalid?"

"She may be. I don't know. She has golden hair."

He gave a gesture of dislike.

"Dreadful! That's enough! I can imagine her,--a die-away creature witha cough and a straw-coloured wig. Yes!--that will do, Manella! You'dbetter go and wait upon her. I've got all I want for a couple of daysat least." He seated himself and took up his note-book. She turned away.

"Stop a minute, Manella!"

She obeyed.

"Golden hair, you said?"

She nodded.

"Old or young?"

"She might be either"--and Manella gazed dreamily at the darkeningsky--"There is nobody old nowadays--or so it seems to me."

"An invalid?"

"I don't think so. She looks quite well. She arrived at the Plaza onlyyesterday."

"Ah! Well, good-night, Manella! And if you want to know anything moreabout me, I don't mind telling you this,--that there's nothing in theworld I so utterly detest as a woman with golden hair! There!"

She looked at him, surprised at his harsh tone. He shook his forefingerat her.

"Fact!" he said--"Fact as hard as nails! A woman with golden hair is ademon--a witch--a mischief and a curse! See? Always has been and alwayswill be! Good-night!"

But Manella paused, meditatively.

"She looks like a witch," she said slowly--"One of those cre

atures theyput in pictures of fairy tales,--small and white. Very small,--I couldcarry her."

"I wouldn't try it if I were you"--he answered, with visibleimpatience--"Off you go! Good-night!"

She gave him one lingering glance; then, turning abruptly picked up herempty milk pail and started down the hill at a run.

The man she left gave a sigh, deep and long of intense relief. Eveninghad fallen rapidly, and the purple darkness enveloped him in its warm,dense gloom. He sat absorbed in thought, his eyes turned towards theeast, where the last stretches of the afternoon's great cloud trailedfilmy threads of woolly black through space. His figure seemedgradually drawn within the coming night so as almost to become part ofit, and the stillness around him had a touch of awe in its impalpableheaviness. One would have thought that in a place of such utterloneliness, the natural human spirit of a man would instinctivelydesire movement,--action of some sort, to shake off the insidiousdepression which crept through the air like a creeping shadow, but thesolitary being, seated somewhat like an Aryan idol, hands on knees andface bent forwards, had no inclination to stir. His brain was busy; andhalf unconsciously his thoughts spoke aloud in words--

"Have we come to the former old stopping place?" he said, as thoughquestioning some invisible companion; "Must we cry 'halt!' for thethousand millionth time? Or can we go on? Dare we go on? If actually wediscover the secret--wrapped up like the minutest speck of a kernel inthe nut of an electron,--what then? Will it be well or ill? Shall wefind it worth while to live on here with nothing to do?--nothing totrouble us or compel us to labour? Without pain shall we be consciousof health?--without sorrow shall we understand joy?"

A sudden whiteness flooded the dark landscape, and a full moon leapedto the edge of the receding cloud. Its rising had been veiled in thedrift of black woolly vapour, and its silver glare, sweeping throughthe darkness flashed over the land with astonishing abruptness. The manlifted his eyes.

"One would think that done for effect!" he said, half aloud--"If themoon were the goddess Cynthia beloved of Endymion, as woman and goddessin an impulse of vanity she would certainly have done that for effect!As it is--"

Here he paused,--an instinctive feeling warned him that some one waslooking at him, and he turned his head quickly. On the slope of thehill where Manella had lately stood, there was a figure, white as thewhite moonlight itself, outlined delicately against the darkbackground. It seemed to be poised on the earth like a bird justlightly descended; in the stirless air its garments appeared closedabout it fold on fold like the petals of an unopened magnolia flower.As he looked, it came gliding towards him with the floating ease of anair bubble, and the strong radiance of the large moon showed itswoman's face, pale with the moonbeam pallor, and set in a wave of hairthat swept back from the brows and fell in a loosely twisted coil likea shining snake stealthily losing itself in folds of misty drapery. Herose to meet the advancing phantom.

"Entirely for effect!" he said, "Well planned and quite worthy of you!All for effect!"