Matilda Montgomerie; Or, The Prophecy Fulfilled

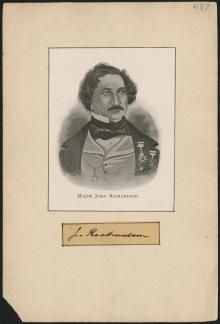

Major Richardson

Produced by Brian Sogard, Shanna D. Bokoff and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note: Bold text denoted by =equal signs=.

MATILDA MONTGOMERIE;

OR,

THE PROPHECY FULFILLED.

A TALE OF THE LATE AMERICAN WAR. BEING THE SEQUEL TO WACOUSTA.

By MAJOR RICHARDSON, AUTHOR OF "WACOUSTA," "HARDSCRABBLE," "ECARTE," ETC., ETC.

NEW YORK: POLLARD & MOSS, 42 Park Place and 37 Barclay Street. 1888.

CHAPTER I.

At the northern extremity of the small town which bears its namesituated at the head of Lake Erie, stands, or rather stood--for thefortifications then existing were subsequently destroyed--the smallfortress of Malden.

Few places in America, or in the world, could, at the period embraced byour narrative, have offered more delightful associations than that whichwe have selected for an opening scene. Amherstburg was at that time oneof the loveliest spots that ever issued from the will of a beneficentand gorgeous nature, and were the world-disgusted wanderer to haveselected a home in which to lose all memory of conventional andartificial forms, his choice would assuredly have fallen here. Andinsensible, indeed, to the beautiful realities of the sweet wildsolitude that reigned around, must that man have been, who could havegazed unmoved from the banks of the Erie, on the placid lake beneath hisfeet, mirroring the bright starred heavens on its unbroken surface, orthrowing into full relief the snow-white sail and dark hull of somestately war-ship, becalmed in the offing, and only waiting the rising ofthe capricious breeze, to waft her onward on her _then_ peaceful missionof dispatch. Lost indeed to all perception of the natural must he havebeen, who could have listened, without a feeling of voluptuousmelancholy, to the plaintive notes of the whip-poor-will, breaking onthe silence of night, and harmonising with the general stillness of thescene. How often have we ourselves, in joyous boyhood, lingered amid thebeautiful haunts, drinking in the fascinating song of this strangenight-bird, and revelling in a feeling we were too young to analyze, yetcherished deeply--yea, frequently, up to this hour, do we in our dreamsrevisit scenes no parallel to which has met our view, even in the courseof a life passed in many climes; and on awaking, our first emotion isregret that the illusion is no more.

Such was Amherstburg and its immediate vicinity, during the early yearsof the present century, and up to the period at which our storycommences. Not, be it understood that even _then_ the scenery itself hadlost one particle of its loveliness, or failed in aught to awaken andfix the same tender interest. The same placidity of earth and sky andlake remained, but the poor whip-poor-will, driven from his customaryabode by the noisy hum of warlike preparation, was no longer heard, andthe minds of the inhabitants, hitherto disposed, by the quiet pursuitsof their uneventful lives, to feel pleasure in its song, had eye or earfor naught beyond what tended to the preservation of their threatenedhomes. It was the commencement of the war of 1812.

Let us, however introduce the reader more immediately to the scene.Close in his rear, as he stands on the elevated bank of the magnificentriver of Detroit, and about a mile from its point of junction with LakeErie, was the fort of Amherstburg, its defences consisting chiefly ofstockade works, flanked, at its several angles, by strong bastions, andcovered by a demi-lune of five guns, so placed as to command everyapproach by water. Distant about three hundred yards on his right, was alarge, oblong, square building, resembling in appearance the red,low-roofed blockhouses peering above the outward defences of the fort.Surrounding this, and extending to the skirt of the thinned forest, theoriginal boundary of which was marked by an infinitude of dingy, halfblackened stumps, were to be seen numerous huts or wigwams of theIndians, from the fires before which arose a smoke that contributed,with the slight haze of the atmosphere, to envelope the tops of the talltrees in a veil of blue vapor, rendering them almost invisible. Betweenthese wigwams and the extreme verge of the thickly wooded banks, whichsweeping in bold curvature for an extent of many miles, brought intoview the eastern extremity of Turkey Island, situated midway betweenAmherstburg and Detroit, were to be seen, containing the accumulatedIndian dead of many years, tumuli, rudely executed, it is true, butpicturesquely decorated with such adornments as it is the custom ofthese simple mannered people to bestow on the last sanctuaries of theirdeparted friends. Some three or four miles, and across the water, (forit is here that the river acquires her fullest majesty of expansion,) isto be seen the American island of Gros Isle, which, at the period ofwhich we write, bore few traces of cultivation--scarcely a habitationbeing visible throughout its extent--various necks of land, however,shoot out abruptly, and independently of the channel running between itand the American main shore, form small bays or harbors in which boatsmay always find shelter and concealment.

Thus far the view to the right of the spectator, whom we assume to befacing the river. Immediately opposite to the covering demi-lune, and infront of the fort, appeared, at a distance of less than half a mile, ablockhouse and battery, crowning the western extremity of the island ofBois Blanc, one mile in length, and lashed at its opposite extremity bythe waters of Lake Erie, which, at this precise point receives into hercapacious bosom the vast tribute of the noble river connecting her withthe higher lakes. Between this island and the Canadian shore lies theonly navigable channel for ships of heavy tonnage, for although thewaters of the Detroit are of vast depth every where above the island,they are near their point of junction with the lake, and, in what iscalled the American channel, so interrupted by shallows and sandbars,that no craft larger than those of a description termed "Durham boats,"can effect the passage--on the other hand the channel dividing theisland from the Canadian shore is at once deep and rapid, and capable ofreceiving vessels of the largest size. The importance of such a passagewas obvious; but although a state of war necessarily prevented aid fromarmed vessels to such forts of the Americans as lay to the westward ofthe lake, it by no means effectually cut off their supplies through themedium of the Durham boats already alluded to. In order to interceptthose, a most vigilant watch was kept by the light gun boats despatchedinto the lesser channel for that purpose.

A blockhouse and battery crowned also the eastern extremity of theisland, and both, provided with a flagstaff for the purpose ofcommunication by signal with the fort, were far from being wanting inpicturesque effect. A subaltern's command of infantry, and abombvadier's of artillery, were the only troops stationed there, andthese were rather to look out for and report the approach of whateverAmerican boats might be seen stealing along their own channel, than withany view to the serious defence of a post already sufficiently commandedby the adjacent fortress. In every other direction the island wasthickly wooded--not a house, not a hut arose, to diversify the wildbeauty of the scene. Frequently, it is true, along the margin of itssands might be seen a succession of Indian wigwams, and the dusky andsinewy forms of men gliding round their fires, as they danced to themonotonous sound of the war dance; but these migratory people seldomcontinuing long in the same spot, the island was again and again left toits solitude.

Strongly contrasted with this, would the spectator, whom we stillsuppose standing on the bank where we first placed him, find the view onhis left. There would he have beheld a small town, composed entirely ofwooden houses variously and not inelegantly painted; and recedinggradually from the river's edge to the slowly disappearing forest, onwhich its latest rude edifice reposed. Between the town and the fort,was to be seen a dockyard of no despicable dimensions, in which the humof human voices mingled with the sound of active labor--there too mightbe seen, in the deep harbor of the narrow channel that separ

ated thetown from the island we have just described, some half-dozen gallantvessels bearing the colors of England, breasting with their dark prowsthe rapid current that strained their creaking cables in every strand,and seemingly impatient of the curb that checked them from glidingimpetuously into the broad lake, which, some few hundred yards below,appeared to court them to her bosom. But although in these might beheard the bustle of warlike preparation, the chief attention would beobserved to be directed towards a large half finished vessel, on whichnumerous workmen of all descriptions were busily employed, evidentlywith a view of preparing for immediate service.

Beyond the town again might be obtained a view of the high andcultivated banks, sweeping in gentle curve until they at lengthterminated in a low and sandy spot, called, from the name of itsproprietor, Elliott's point. This stretched itself towards the easternextremity of the island, so as to leave the outlet to the lake barelywide enough for a single vessel to pass at a time, and that not withoutskilful pilotage and much caution.

Assuming the reader to be now as fully familiar with the scene asourselves, let him next, in imagination, people it, as on the occasionwe have chosen for his introduction. It was a warm, sunny day, in theearly part of July. The town itself was as quiet as if the glaive of warreposed in its sheath, and the inhabitants pursued their wontedavocations with the air of men who had nothing in common with the activeinterest which evidently dominated the more military portions of thescene. It was clear that among these latter some cause for excitementexisted, for, independently of the unceasing bustle within thedockyard--a bustle which however had but one undivided object, thecompletion and equipment of the large vessel then on the stocks--theimmediate neighborhood of the fort presented evidence of some more thanordinary interest. The encampment of the Indians on the verge of theforest, had given forth the great body of their warriors, and these cladin their gayest apparel, covered with feathers and leggings of brightcolors, decorated with small tinkling bells that fell not inharmoniouslyon the ear, as they kept tune to the measured walk of their proudwearers, were principally assembled around and in front of the largebuilding we have described as being without, yet adjacent to, the fort.These warriors might have been about a thousand in number, andamused themselves variously--(the younger at least)--withleaping--wrestling--ball-playing--and the foot race--in all whichexercises they are unrivalled. The elders bore no part in theseamusements, but stood, or sat cross-legged on the edge of the bank,smoking their pipes, and expressing their approbation of the prowess ordexterity of the victors in the games, by guttural, yet rapidly utteredexclamations. Mingled with these were some six or seven individuals,whose glittering costume of scarlet announced them for officers of thegarrison, and elsewhere disposed, some along the banks and crowding thebattery in front of the fort, or immediately round the building, yetquite apart from their officers, were a numerous body of the inferiorsoldiery.

But although these distinct parties were assembled, to all appearance,with a view, the one to perform in, the other to witness, the activesports we have enumerated, a close observer of the movements of allwould have perceived there was something more important incontemplation, to the enactment of which these exercises were but theprelude. Both officers and men, and even the participators in thesports, turned their gaze frequently up the Detroit, as if they expectedsome important approach. The broad reach of the wide river, affording anundisturbed view, as we have stated, for a distance of some nine or tenmiles, where commenced the near extremity of Turkey Island, presentednothing, however, as yet, to their gaze, and repeatedly were thetelescopes of the officers raised only to fall in disappointment fromthe eye. At length a number of small dark specks were seen studding thetranquil bosom of the river, as they emerged rapidly, one after theother, from the cover of the island. The communication was made, by himwho first discovered them, to his companions. The elder Indians who satnear the spot on which the officers stood, were made acquainted withwhat even their own sharp sight could not distinguish unaided by theglass. One sprang to his feet, raised the telescope to his eye, and withan exclamation of wonder at the strange properties of the instrument,confirmed to his followers the truth of the statement. The elders,principally chiefs, spoke in various tongues to their respectivewarriors. The sports were abandoned, and all crowded to the bank withanxiety and interest depicted in their attitudes and demeanor.

Meanwhile the dark specks upon the water increased momentarily in size.Presently they could be distinguished for canoes, which, rapidlyimpelled, and aided in their course by the swift current, were not longin developing themselves to the naked eye. These canoes, about fifty innumber, were of bark, and of so light a description, that a man ofordinary strength might, without undergoing serious fatigue, carry onefor miles. The warriors who now propelled them, were naked in all savetheir leggings and waist cloths, their bodies and faces begrimed withpaint: and as they drew near, fifteen was observed to be the complementof each. They sat by twos on the narrow thwarts; and, with their facesto the prow, dipped their paddles simultaneously into the stream, with aregularity of movement not to be surpassed by the most experiencedboat's crew of Europe. In the stern of each sat a chief guiding his barkwith the same unpretending but skilful and efficient paddle, and behindhim drooping in the breezeless air, and trailing in the silvery tide,was to be seen a long pendant, bearing the red cross of England.

It was a novel and beautiful sight to behold that imposing fleet ofcanoes, apparently so frail in texture that the dropping of a pebblebetween the skeleton ribs might be deemed sufficient to perforate andsink them, yet withal so ingeniously contrived as to bear safely notonly the warriors who formed their crews, but also their arms of alldescriptions, and such light equipment of raiment and necessaries aswere indispensable to men who had to voyage long and far in pursuit ofthe goal they were now rapidly attaining. The Indians already encampednear the fort, were warriors of nations long rendered familiar bypersonal intercourse, not only with the inhabitants of the district, butwith the troops themselves; and these, from frequent association withthe whites, had lost much of that fierceness which is so characteristicof the North American Indian in his ruder state. Among these, with themore intelligent Hurons, were the remnants of those very tribes ofShawnees and Delawares whom we have recorded to have borne, half acentury ago, so prominent a share in the confederacy against England,but who, after the termination of that disastrous war, had so farabandoned their wild hostility, as to have settled in various points ofcontiguity to the forts to which they, periodically, repaired to receivethose presents which a judicious policy so profusely bestowed.

The reinforcement just arriving was composed principally of warriors whohad never yet pressed a soil wherein civilization had extended herinfluence--men who had never hitherto beheld the face of a white, unlessit were that of the Canadian trader, who, at stated periods, penetratedfearlessly into their wilds for purposes of traffic, and who to thebronzed cheek that exposure had rendered nearly as swarthy as their own,united not only the language but so wholly the dress--or rather theundress of those he visited, that he might easily have been confoundedwith one of their own dark-blooded race. So remote, indeed, were theregions in which some of these warriors had been sought, that they werestrangers to the existence of more than one of their tribes, and uponthese they gazed with a surprise only inferior to what they manifested,when, for the first time, they marked the accoutrements of the Britishsoldier, and turned with secret, but acknowledged awe and admirationupon the frowning fort and stately shipping, bristling with cannon, andvomiting forth sheets of flame as they approached the shore. In thesemight have been studied the natural dignity of man. Firm of step--proudof mien--haughty and penetrating of look, each leader offered in his ownperson a model to the sculptor, which he might vainly seek elsewhere.Free and unfettered every limb, they moved in the majesty of nature, andwith an air of dark reserve, passed, on landing, through the admiringcrowd.

There was one of the number, however, and his canoe was decorated

with aricher and a larger flag, whose costume was that of the more civilizedIndians, and who in nobleness of deportment, even surpassed those wehave last named. This was Tecumseh. He was not of the race of either ofthe parties who now accompanied him, but of one of the nations, many ofwhose warriors were assembled on the bank awaiting his arrival. As thehead chief of the Indians, his authority was acknowledged by all, evento the remotest of these wild but interesting people, and the result ofthe exercise of his all-powerful influence had been the gatheringtogether of those warriors, whom he had personally hastened to collectfrom the extreme west, passing in his course and with impunity, theseveral American posts that lay in their way.

It was amidst the blaze of a united salvo from the demi-lune crowningthe bank, and from the shipping, that the noble chieftain, accompaniedby the leaders of those wild tribes, leaped lightly, yet proudly to thebeach; and having ascended the steep bank by a flight of rude steps cutout of the earth, finally stood amid the party of officers waiting toreceive them. It would not a little have surprised a Bond streetexquisite of that day to have witnessed the cordiality with which thedark hand of the savage was successively pressed in the fairer palms ofthe English officers, neither would his astonishment have been abated,on remarking the proud dignity of carriage maintained by the former, inthis exchange of courtesy, as though, while he joined heart to handwherever the latter fell, he seemed rather to bestow than to receive acondescension.

Had none of those officers ever previously beheld him, the fame of hisheroic deeds had gone sufficiently before the warrior to have insuredhim their warmest greeting and approbation, and none could mistake aform that, even amid those who were a password for native majesty, stoodalone in its bearing; but Tecumseh was a stranger to few. Since hisdefeat on the Wabash he had been much at Amherstburg where he hadrendered himself conspicuous by one or two animated and highly eloquentspeeches, having for their object the consolidation of a treaty, inwhich the Indian interests were subsequently bound in close union withthose of England; and, up to the moment of his recent expedition, hadcultivated the most perfect understanding with the English chiefs.

It might, however, be seen that even while pleasure and satisfaction ata reunion with those he in turn esteemed, flashed from his dark andeager eye, there was still lurking about his manner that secret jealousyof distinction, which is so characteristic of the haughty Indian. Afterthe first warm salutations had passed, he became sensible of the absenceof the English chief; but this was expressed rather by a certainoutswelling of his chest, and the searching glance of his restless eye,than by any words that fell from his lips. Presently, he whom he sought,and whose person had hitherto been concealed by the battery on the bank,was seen advancing towards him, accompanied by his personal staff. In amoment the shade passed away from the brow of the warrior, and warmlygrasping and pressing, for the second time, the hand of a youth--one ofthe group of junior officers among whom he yet stood, and who hadmanifested even more than his companions the unbounded pleasure he tookin the chieftain's re-appearance--he moved forward, with an ardor ofmanner that was with difficulty restrained by his sense of dignity, togive them the meeting.

The first of the advancing party was a tall, martial looking man,wearing the dress and insignia of a general officer. His rather floridcountenance was eminently fine, if not handsome, offering, in its moreRoman than Grecian contour, a model of quiet, manly beauty; while theeye beaming with intelligence and candor, gave, in the occasionalflashes which it emitted, indication of a mind of no common order. Therewas, notwithstanding, a benevolence of expression about it that blended(in a manner to excite attention) with a dignity of deportment, as muchthe result of habitual self command, as of the proud eminence ofdistinction on which he stood. The sedative character of middle age,added to long acquired military habits, had given a certain rigidity tohis fine form, that might have made him appear to a first observer evenolder than he was, but the placidity of a countenance beaming good willand affability, speedily removed the impression, and, if the portlyfigure added to his years, the unfurrowed countenance took from them inequal proportion.

At his side, hanging on his arm and habited in naval uniform, appearedone who, from his familiarity of address with the General, not less thanby certain appropriate badges of distinction, might be known as thecommander of the little fleet then lying in the harbor. Shorter inperson than his companion, his frame made up in activity what it wantedin height, and there was that easy freedom in his movements which sousually distinguishes the carriage of the sailor, and which now offereda remarkable contrast to that rigidity we have stated to have attached,albeit unaffectedly, to the military commander. His eyes, of a muchdarker hue, sparkled with a livelier intelligence, and although hiscomplexion was also highly florid, it was softened down by the generalvivacity of expression that pervaded his frank and smiling countenance.The features, regular and still youthful, wore a bland and pleasingcharacter; while neither, in look, nor bearing, nor word could there betraced any of that haughty reserve usually ascribed to the "lords of thesea." There needed no other herald to proclaim him for one who hadalready seen honorable service, than the mutilated stump of what hadonce been an arm: yet in this there was no boastful display, as of onewho deemed he had a right to tread more proudly because he had chancedto suffer, where all had been equally exposed, in the performance of acommon duty. The empty sleeve, unostentatiously fastened by a loop fromthe wrist to a button of the lapel, was suffered to fall at his side,and by no one was the deficiency less remarked than by himself.

The greeting between Tecumseh and these officers, was such as might beexpected from warriors bound to each other by mutual esteem. Each heldthe other in the highest honor, but it was particularly remarked thatwhile the Indian Chieftain looked up to the General with the respect hefelt to be due to him, his address to his companion, whom he now beheldfor the first time, was warmer, and more energetic; and as he repeatedlyglanced at the armless sleeve, he uttered one of those quick ejaculatoryexclamations, peculiar to his race, and indicating, in this instance,the fullest extent of approbation. The secret bond of sympathy whichchained his interest to the sailor, might have owed its being to anothercause. In the countenance of the latter there was much of that eagernessof expression, and in the eye that vivacious fire, that flashed, even inrepose, from his own swarthier and more speaking features; and thisassimilation of character might have been the means of producing thatpreference for, and devotedness to, the cause of the naval commander,that subsequently developed itself in the chieftain. In a word, theGeneral seemed to claim the admiration and the respect of theIndian--the Commodore, his admiration and friendship.

The greeting between these generous leaders was brief. When the firstsalutations had been interchanged, it was intimated to Tecumseh, throughthe medium of an interpreter then in attendance on the General, that awar-council had been ordered, for the purpose of taking intoconsideration the best means of defeating the designs of the Americans,who, with a view to offensive operations, had, in the interval of thewarrior's absence, pushed on a considerable force to the frontier. Thecouncil, however, had been delayed, in order that it might have thebenefit of his opinions and of his experience in the peculiar warfarewhich was about to be commenced.

Tecumseh acknowledged his sense of the communication with the boldfrankness of the inartificial son of nature, scorning to conceal hisjust self-estimate beneath a veil of affected modesty. He knew his ownworth, and while he overvalued not one iota of that worth, so did he notaffect to disclaim a consciousness of the fact--that within his swarthychest and active brain, there beat a heart and lived a judgment, asprompt to conceive and execute as those of the proudest _he_ that everswayed the destinies of a warlike people. Replying to the complimentaryinvitation of the General, he unhesitatingly said he had done well toawait his arrival, before he determined on the course of action, andthat he should now have the full benefit of his opinions and advice.

If the chief had been forcibly prepossessed in favor

of the navalcommander the latter had not been less interested. Since his recentarrival to assume the direction of the fleet, Commodore Barclay had hadopportunities of seeing such of the chiefs as were then assembled atAmherstburg; but great as had been his admiration of several of these,he had been given to understand they fell far short, in every moral andphysical advantage, of what their renowned leader would be found topossess, when, on his return from the expedition in which he wasengaged, fitting opportunity should be had of bringing them in personalproximity. This admission was now made in the fullest sense, and as thewarrior moved away to give the greetings to the several chiefs, andconduct them to the council hall, the gallant sailor could not refrainfrom expressing in the warmest terms to General Brock, as they movedslowly forward with the same intention, the enthusiastic admirationexcited in him by the person, the manner, and the bearing, of the nobleTecumseh.

Again the cannon from the battery and the shipping pealed forth theirthunder. It was the signal for the commencement of the council, and thescene at that moment was one of the most picturesque that can well beimagined. The sky was cloudless, and the river, no longer ruffled by thenow motionless barks of the recently arrived Indians, yet obeying theaction of the tide, offered, as it glided onward to the lake, the imageof a flood of quicksilver; while, in the distance that lake itself,smooth as a mirror, spread far and wide. Close under the bank yetlingered the canoes, emptied only of their helmsmen (the chiefs of theseveral tribes,) while with strange tongues and wilder gestures, thewarriors of these, as they rested on their paddles, greeted the loudreport of the cannon--now watching with eager eye the flashes from thevessel's sides, and now upturning their gaze, and following with wildsurprise, the deepening volumes of smoke that passed immediately overtheir heads, from the guns of the battery, hidden from their view bythe elevated and overhanging bank. Blended with each discharge arose thewild yell, which they, in such a moment of novel excitement, felt itimpossible to control, and this, answered by the Indians above, andborne in echo almost to the American shore, had in it somethingindescribably grand and startling. On the bank itself the scene wassingularly picturesque. Here were to be seen the bright uniforms of theBritish officers, at the head of whom was the tall and martial figure ofGeneral Brock, furthermore conspicuous from the full and droopingfeather that fell gracefully over his military hat, mingled with thewilder and more fanciful head-dresses of the chiefs. Behind these again,and sauntering at a pace that showed them to have no share in thedeliberative assembly, whither those we have just named were nowproceeding, amid the roar of artillery, yet mixed together in nearly asgreat dissimilarity of garb, were to be seen numbers of the inferiorwarriors and of the soldiery--while, in various directions, the gamesrecently abandoned by the adult Indians were now resumed by mere boys.The whole picture was one of strong animation, contrasting as it didwith the quiet of the little post on the Island, where some twelve orfifteen men, composing the strength of the detachment, were sitting orstanding on the battery, crowned, as well as the fort and shipping, andin compliment to the newly arrived Indians, with the colors of England.

Such was the scene, varied only as the numerous actors in it variedtheir movements, when the event occurred with which we commence our nextchapter.