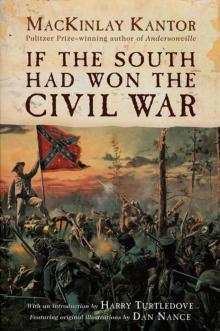

If the South Had Won the Civil War

MacKinlay Kantor

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Introduction by Harry Turtledove

If the South Had Won the Civil War

An Historical Inversion

Forge Books by MacKinlay Kantor

Copyright

INTRODUCTION BY HARRY TURTLEDOVE

If the South Had Won the Civil War is, I think, the first work of alternate history I ever found. Almost forty years ago my ninth-grade English teacher kept a couple of shelves of paperbacks that her students could read if they finished assignments early—better that they read, she reasoned, than raise a ruckus, as ninth-graders with time on their hands are only too likely to do. Those shelves included out-and-out science fiction, which was plenty to lure me over: I remember an A. E. van Vogt novel and a Judith Merril year’s-best anthology. And they also included If the South Had Won the Civil War.

MacKinlay Kantor’s slim work of speculation was not presented as science fiction. I doubt that Kantor himself thought of it as science fiction; that was not where his main field of interest lay. He is best remembered today for Andersonville, arguably the greatest Civil War novel of all time, a harrowing, meticulously researched, and splendidly written tale of the Confederate prisoner-of-war camp in Georgia. But Andersonville is only the high point of a writing career that spanned more than half a century.

He began at seventeen, as a newspaperman on his hometown paper, the Webster City [Iowa] Daily News (the fact that his mother edited the Daily News probably didn’t hurt). His first novel, Diversey, was published in 1928, when he was twenty-four. His first bestseller, Long Remember, came out in 1934. After Hollywood bought the rights to it, Kantor moved from Iowa to California to work as a screenwriter. During World War II, he was a correspondent covering the air war in the European theater. His 1945 novel, Glory for Me, was made into the film The Best Years of Our Lives. Andersonville appeared in 1955 and won the Pulitzer Prize for literature. Along with hundreds of short stories, articles, essays, and poems, Kantor published thirty-two books, the last of which, Valley Forge, appeared not long before his death in 1977.

The alternate world of If the South Had Won the Civil War departs from ours in two places in 1863: in the accidental death of Ulysses S. Grant during his advance upon Vicksburg and the disastrous failure of the campaign following his loss, and a Confederate victory at Gettysburg. Had these events turned out as Kantor described, there would be little doubt that the Confederate States would have won their independence on the battlefield.

Establishing the historical breakpoint (or, in this case, twin breakpoints) is only half the game of writing alternate history. The other half, and to me the more interesting one, is imagining what would spring from the proposed change. It is in that second half of the game that science fiction and alternate history come together. Both seek to extrapolate logically from a change in the world as we know it. Most forms of science fiction posit a change in the present or nearer future and imagine its effect on the more distant future. Alternate history, on the other hand, imagines a change in the more distant past and examines its consequences for the nearer past and the present. The technique is the same in both cases; the difference lies in where in time it is applied.

One of the amusing and enjoyable games the writer of alternate history can play is looking at the lives of prominent people under changed circumstances. For instance, what would Alexander the Great have done if his father, Philip of Macedon, hadn’t been murdered in 336 BC? In more modern times, what sort of career would John F. Kennedy have had if he himself had escaped assassination in 1963?

Kantor plays this game as well as anyone. For example, at the time of the outbreak of the First World War, he imagines Theodore Roosevelt as President of the United States and Woodrow Wilson as President of the Confederate States (along with one Roy Smith as President of the Republic of Texas, which he envisions seceding from the CSA). The choices of Roosevelt and Wilson cannot, I think, be improved upon for dramatic potential at this crucial time in the history of America and of the world. That being so, I also used them as heads of the USA and CSA, respectively, in my own very different alternate World War I, the Great War series. Sometimes something seems so perfectly right, one has to use it even if it has been done before.

Many alternate histories are dystopias: they create worlds worse than our own and use them to point out our failings and foibles. The continued interest in books where the Axis won the Second World War (perhaps the finest of which, Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, appeared not long after If the South Had Won the Civil War) is a case in point. But Kantor’s work is a genial exception to the rule. Written just before the centennial of the Civil War (it first ran in the November 22, 1960, issue of Look), it takes as its thesis that Americans would have stayed very much alike and maintain close ties to one another regardless of whether they chanced to live under the Stars and Stripes, the Stars and Bars, or the Lone Star Flag.

Is that true? Who knows? In any case, it’s the wrong question to ask of a work of alternate history. This is fiction, after all, and should be judged like any other piece of fiction. Is it entertaining? Is it plausible? Is it thought-provoking? Yes, on all three counts. For that reason, I am honored to have the privilege of writing this introduction and delighted that If the South Had Won the Civil War is back in print more than forty years after its original appearance.

IF THE SOUTH HAD WON THE CIVIL WAR

The Past is immutable as such. Yet, in Present and in Future, its accumulated works can be altered by the whim of Time.…

As we enter the centennial of those military events which assured to the Confederate States of America their independence, it seems incumbent upon the historian to review a pageant bugled up from dusty lanes of the nineteenth century, to comment upon the actors appearing in such vast procession, and to inquire into the means by which they galloped toward fame or ignominy.

(If one would wish to apply this scrutiny to earlier epochs, he might in the same manner ask himself what would have befallen had winds not torn the canvas of the Spanish Armada?—had the Pilgrims landed on that Virginia coast for which they were originally primed?—had the boat bearing Washington capsized in the Delaware River?—had Pakenham been able to sweep triumphantly across the cotton-bale breastworks at New Orleans?)

Fruit of history contains many seeds of truth; yet unglimpsed orchards might have bloomed profusely in any season, were all the seeds planted and cultured before they dried past hope of germination.

Our American Civil War ended abruptly in July, 1863, with the shattering of the two most puissant armies which the North had been able to muster and marshal.

There was no more rebellion. Instead there had been a revolution, and the success of that enterprise now became assured—first, in Mississippi—and, almost simultaneously, some fourteen hundred miles away, among the green ridges which bend across the Pennsylvania-Maryland line.

* * *

The death of Major General U. S. Grant came as a sickening shock to those Northerners who had held high hopes for a successful campaign in the

West—for the reduction of Port Hudson and Vicksburg, and the freeing of the Mississippi River from Confederate domination.

Monumental effects of the catastrophe (Grant’s death) could not be observed for nearly seven weeks, such was the confusion of operations within the State of Mississippi.

The fatal accident befell in the late afternoon of Tuesday, May 12th, 1863, on a narrow road winding among hills of Hinds County, Mississippi. (This was some forty-eight hours after Lieutenant General “Stonewall” Jackson breathed his last, in distant Virginia, and while officials and supporters of the National Government were still swallowing the acid of Chancellorsville.)

Grant had left Grand Gulf on May 7th, deliberately cutting himself off from his base of supplies. He fared into the field with only the barest staples for those three army corps under his command, and with problems of transport to be solved by the acquisition of civilian vehicles. His projected march might have been considered Napoleonic in its conception and in its rashness, though future historians would censure Grant for having projected a suicidal venture. It must be remembered, however, that the springtime campaign had thus far moved with celerity. Union gunboats and steamers had successfully run the blockade at Vicksburg on the moonless night of April 16th; and Grant had marched his troops across a vast western bend of the Mississippi, in order to be picked up by the fleet—below Vicksburg, far out of interference by Confederate batteries—and transported to the east bank of the Mississippi River.

Lieutenant General John Pemberton, venturing out from the defenses of Vicksburg, was still mainly inactive. General Joseph E. Johnston had not yet assumed command of the Confederate forces at and near Jackson. Grant was now pressing his advance through unoccupied country between two hostile armies. But he had left himself with no vulnerable rear for Pemberton to fall upon.

Grant was traditionally given to taciturnity and self-consultation. No one knows exactly what was in his mind. It is believed that he intended to throw himself against Jackson, capture the State capital, and cut the railroad leading from Jackson to Vicksburg, thus depriving the besieged river bastion of any possibility for supply or reinforcement.

On May 12th, the Union advance had pressed beyond Fourteen Mile Creek. Major General John A. McClernand’s Corps was moving on the left, with its flank held firmly against the Big Black River. By late afternoon McClernand had shoved across Fourteen Mile Creek; his pickets were within two miles of Edwards Station on the Vicksburg & Jackson Railroad. Major General Wm. T. Sherman held the center of the northward-turning Union advance. Major General James B. McPherson held the right. That afternoon elements of McPherson’s Corps encountered the Confederate Brigadier General Gregg, with a moderate force, near Raymond. Major General John A. Logan’s Division attacked speedily, and, after a brief but spirited encounter, nullified the Confederate resistance and sent Gregg in rapid retreat.

Orders for the next day, for specific movements on specific roads, had already been issued. Then Grant received his despatch from McPherson, telling of McPherson’s successful drive upon Raymond.

Many historians believe that decisively Grant might have altered his plans for movements on the 13th, had he lived a little longer.

Grant was accompanying the command of his admired and admiring “Cump” Sherman. In addition to his regular staff, Grant had in his peripatetic military household his son Frederick, twelve years of age. There was also present the journalist, Mr. Charles A. Dana, later named to be Assistant Secretary of War.

A few days afterward Dana wrote to a friend: “General Grant took the despatch and read it twice. He did not immediately discuss the contents of the note with anyone, but this was not unusual. He pocketed the envelope; there was a look of satisfaction on his face. He was mounted when he received the despatch, and remained in his saddle throughout the reading.”

Two of Grant’s favorite steeds had gone lame. Grant was riding a fractious horse, one which his groom had not wished him to ride. But the general, a master of equitation, would not brook the delay necessary to the finding of another mount. He had ridden the big chestnut since noon, although frequently he was observed as having difficulty in keeping the beast under control.

There was the usual coterie of lookers-on present in the neighborhood: gaunt farm boys, little girls, a few Negroes. These clung in fence corners or at crossroads, glowering or looking gleeful or merely awed, as is the habit of civilians in an area traversed by armies.

Grant’s horse first became unsettled because of the blast of a whistle from Fairchild’s steam mill, located nearby. There was a head of steam up in the boiler. It was said later that the first officers who moved in the advance wished steam to be kept up in the mill for some military purpose. This was never explained. But when a foolish blast from the whistle ensued, Grant’s horse was seen to grow increasingly nervous.

Edward H. Sittenfield, later U.S. senator from Illinois and then serving as a staff major, writes:*

“I had noticed that a little girl was huddled on a rail fence, holding a cat wrapped in a shawl in her lap. Perhaps Kitty scratched the child. At any rate she dropped the cat, and the next moment it was pursued by a large white-and-tan hound. The speeding animals dashed across the roadway directly in front of Grant’s horse. Someone cried out, so we all turned. There were many witnesses to this occurrence.”

Grant’s mount rose tall upon its hind legs, then flung itself to one side with a desperate whinny. No horseman in the world could have held his seat in such a shying. Even as it reared the horse lost footing in the clay road and pitched heavily to one side, landing half on its back, with the rider underneath, receiving the weight of the crushing flailing body.

There was also the matter of the rock: a fair-sized whitish stone, washed out from clay at that point. Some witnesses insist that Grant’s head struck the rock—there was blood upon the stone when they removed the fallen general. Others give contrary information. But whatever his injuries, and however received, the commander of the Army of the Tennessee now lay unconscious. The horse was writhing, inflicting fresh injuries upon the recumbent body beneath it at every move.

A young staff captain, Hubert Gaines, had the presence of mind to swing from his horse and run forward, drawing his revolver in the same moment. He fired two shots into the animal’s ear and the great beast lay still. Then Grant could be removed—his uniform covered with clay, and blood issuing from his nose and mouth. Mr. Charles A. Dana himself escorted the white-faced little Frederick Grant away.

Ulysses Grant spoke no coherent word. As people placed him tenderly upon a hastily-improvised couch of blankets his respiration was labored and his pulse weak. A surgeon was found (after some fifteen minutes, during which time others tried to render what aid they could). When he arrived the surgeon pronounced Grant dead.

Sittenfield writes feelingly: “Another month, another hour, another place? What might have been the historical residue? Suppose, let us say, that General Grant had never suffered such an accident until after the termination of his Mississippi campaign. We cannot help but hold that, with his presence and guiding direction and genius, there would have been a far different result to that same campaign. Let us suppose further that a shying horse had fallen upon him three months later—perhaps in August, perhaps not in the field, but in a region won by the investment of Federal arms, and saved by the application of Grant’s own genius. What would the result have been? It would have been negative, it might in no way have affected the immediate conduct of the war. Only in the long view would this same tragedy have obtained. Let us suppose still further, perhaps, that the fall did not result fatally. A few painful weeks in bed, and then up and about on crutches, and returning eventually to active command in the field! Ah, the great chargers of history pass before us now, from Bucephalus on to George Washington’s famous Blueskin; and the fractious chestnut ridden by U. S. Grant on May 12, 1863, takes a shamed place in the rearguard!”

* * *

McClernand ranked both W. T. Sherma

n and J. B. McPherson, and on his arrogant shoulders there now fell a mantle which draped him almost ludicrously.

The speed and agility of the Army of the Tennessee was departed—it might have oozed away in the last outpouring of Ulysses Grant’s blood.

Either of the two West Pointers would have been far more fitted to command; but the distant Halleck (despite his dislike for McClernand) was never a man to slice sharply to the quick of a matter. Nor, it must be confessed, was Abraham Lincoln, especially where one of his own military appointments was concerned. That pompous unruly Illinois politician, John A. McClernand, had been given his commission originally because he was a Democratic congressman—from Lincoln’s own district—who had been the Chief Executive’s friend before the war, and remained his supporter in time of later argument and peril. The friendship of Democratic congressmen to the war effort was needed sorely—and perhaps, Lincoln appeared to believe, in the army as well. McClernand was a cackling middle-aged chicken who had come home to roost.

Despite Grant’s removal from existence, and subsequent military misfortunes resulting to the Unionists, their campaign so auspiciously begun might still have been concluded successfully had the Confederate President and his two field commanders, Johnston and Pemberton, descended into contradiction and confusion. Joseph E. Johnston, plagued by dysentery, and suffering still from severe wounds received in 1862, made record speed when ordered from Tullahoma to Jackson. Having arrived at the Mississippi capital and become familiar with the situation, he ordered Pemberton to move on Clinton immediately, with the intention of sweeping aside any Federal troops in his path and effecting a juncture with the Southern reinforcements hastening toward Jackson.

President Jefferson Davis, previously committed to an opinion that Pemberton should retain the bulk of his army in the Vicksburg area, was now converted to Johnston’s belief: i.e., that a general engagement with the Northerners, if delayed until a juncture of Confederate arms was completed, might (as Davis wrote later) “render retreat or reinforcement to the enemy scarcely practicable.” Pemberton, capricious and stubbornly assertive prior to that hour, responded to Johnston’s orders with alacrity.