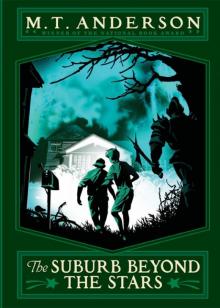

The Suburb Beyond the Stars

M. T. Anderson

The

SUBURB

BEYOND

THE

STARS

The Norumbegan Quartet

Volume 2

M. T. ANDERSON

To N.

in the house of hair.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

Preview

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright

ONE

Brian Thatz noticed he was being followed as he walked from his cello lesson to the old office building where he played interdimensional games.

At first, it was just a feeling that someone was watching. He pushed his glasses more securely onto the bridge of his nose and looked around. No one seemed suspicious. There were some other students with violins and guitars hopping down the steps of the music school. A crossing guard. Two women in high heels, wobbling on the brick sidewalks.

So Brian kept walking, dragging his cello. Sometimes he wished he’d chosen a smaller instrument. Even the viola would have been better.

But there was the feeling again — like someone lightly touching his back, a gaze lingering on his collar, on his neck, on the fringe of hair coming out from under his baseball cap.

He frowned and glanced at the windows he passed to see if they reflected signs of movement.

Nothing. But the feeling persisted. He kept going for a block or two, then turned.

This time, he saw who was following him.

The man wore a camel-hair overcoat and carried nothing in his hands. His face, at a distance, was a violent and bloody red.

Brian loved to read old detective stories with names like The Gimleyhough Diamond, A Wee Case of Murder, and What Goes Up. In these books, people were always being hired to follow other people. They called it “shadowing,” and the creeps who shadowed were called “shadows” or “tails.”

Brian’s shadow was not very good at remaining unseen. The man clearly was used to following sly, nimble victims who slipped through crowds and darted down alleyways. He wasn’t particularly gifted when it came to lurking behind a stocky boy struggling down the street with a cello. The shadow had to make frequent stops so he wouldn’t walk right past Brian. He had to pretend he was interested in birds.

There were plenty of birds. It was early summer in Cambridge, and the Common was alive with them. An oak shuffled with finches. Brian saw the tail pause about fifteen feet back to shield his eyes and admire them. The man’s red face was riddled with old pockmarks, scumbled like cottage cheese.

While the tail watched the finches, Brian decided to make a break for the subway station. He lifted his cello — cranking up his elbows — and hopped across the puddles. For blocks, he puffed and hauled.

Even he could tell his burst of speed was pathetic. College students taking a brisk stroll walked right past him. Bicyclists nearly ran into him. The tail kept ambling along across the Common, fascinated by jays, looking fitfully at the dirty sky, slightly embarrassed to be so visible.

The tail followed Brian past a bus stop, past an old graveyard, past a church and a drunken busker playing the accordion. The man followed him past a newsstand and down the escalators to the T, Boston’s subway.

When the train pulled into the station and the doors hissed and rattled open, Brian lunged into the nearest car. He rested his back against one of the poles and twisted his neck to look out. The tail was headed along the platform, straight for the same car. The man stepped in at the other end and stood staring, unperturbed. No longer, apparently, so interested in birds.

“Ashmont train,” the voice on the loudspeaker said. “Stand clear of the doors. Stand clear.”

Brian flung himself toward the doors as they shut. He hauled his cello behind him.

His cello got tangled with the pole and seat. Brian tripped and almost fell.

“Whoa,” said a kid in a hoodie, gripping Brian’s shoulder. “Steady.”

Now there was no way he could get off in time. The doors were closed. The train pulled out of the station. The tail stared down the car as if Brian were a natural event he was watching. They all raced through tunnels, wheels screaming.

Brian knew who might have sent the man to shadow him. Nearly a year before, Brian and his friend Gregory had gone on a strange adventure in the northern woods of Vermont. They had found themselves the pawns in an ancient, supernatural game that led to mountaintops, caverns, and ogres. When Brian won the Game, he had also won the right to oversee the Game’s next round. Now he suspected that the tail who now stood a few feet from him had been sent by the Thusser, the elfin nation that had lost that contest. Perhaps they were trying to gain some advantage.

Maybe this man, the shadow with clotted cheeks, was sent to find out where Brian’s workshop was hidden. Several days a week after school, Brian went to an old office building, where he and Gregory set up the next round of the Game, making up riddles and designing monstrosities. Maybe the Thusser were trying to catch a glimpse of Brian’s plans.

Or maybe they sought revenge.

Brian thought carefully about what to do. He prided himself on always being rational and logical. He knew that in a few stops, the T train would shoot briefly above-ground. It would cross a bridge over the Charles River, and for a minute or so, his phone would work. He decided he would call Gregory and tell him he wasn’t going to the workshop today. He’d ask Gregory to meet him at a different stop instead, and they’d both just walk back to Brian’s house. That way they wouldn’t be giving the tail any new information. There was nothing secret about Brian’s own address. It could be found by anyone with a phone book and thumbs.

Brian took his phone out of his pocket. He waited for the train to rise out of the tunnel. He anxiously flipped the phone open and closed, open and closed.

As the subway neared the mouth of the tunnel, he speed-dialed Gregory. He held the phone up to his ear. It was ringing.

The tail watched Brian call. His blotched lips started to move, as if he whispered information to someone who couldn’t be seen. He closed his eyes.

The train rolled across a dark granite bridge between black turrets. The city of Boston was spread out on its hill. Sailboats were on the river, and people were jogging along the banks. Brian knew he only had about forty-five seconds. The phone was still ringing.

The train stopped at the Charles Street station. People got on and off, hefting backpacks. Brian hunched over the phone, shielding his face with his cello, which rested between his legs and the grasp bar. The phone rang on.

Then, finally, someone answered.

“Hey,” said Gregory’s voice. “Listen to this.”

“No, Gregory,” whispered Brian urgently. “There’s someone following me. Can you meet me at —”

There was a squalling noise at the other end of the phone, a vicious hissing, a crash.

“Did you hear that?” Gregory said. “I put the cat on my

dad’s turntable. Like, for vinyl.”

“Yeah. Gregory, I’m being followed. One of the Thusser, I think. Can you meet me at —”

There was another sharp hiss, another thump.

Gregory came back on the phone. “Side B,” he explained.

“Gregory, listen!”

“How did people ever think that was a high-definition sound system?”

“Gregory, I need you to meet me at —”

The train sped back underground. Brian shouted the name of a stop, but his phone had already lost its signal.

He was on his own.

He hated that. It was much easier to be brave when there was someone else to rely on. Brian was used to relying on Gregory. Nervously rocking the handle of his cello case back and forth, he considered what he was going to do.

He was supposed to change trains at the next stop, Park Street, where a lot of people stepped off the train or on. But he stayed put, half an eye turned to watch his pursuer. He thought to himself grimly that this was not the first time the Thusser had tailed him on a train. That was how the Game had begun. It had ended with the Thusser agent trying to kill Brian on the floor of a subterranean cathedral. Just thinking about it made Brian panic.

He waited two stops. Then, at the third, just as people were scrambling for seats and the doors were about to close — at the very last minute — Brian seized his cello and forced his way out onto the platform.

The rush-hour crowd was all around him. They still fought to get onto the train. He dodged between them, yanking the cello clumsily behind him. He looked back and saw the camel-hair shadow shoving his way out through the doors, peering around the station. Brian ducked and, slanting the cello like artillery, moved along the wall. He found a column and hid behind it.

He waited. The train pulled away. Another train pulled in. He heard the doors open and people get out. He heard the subterranean voice of the conductor announce the line and the next station. The doors shut. The train moved on.

There was now an awful wailing. It was not the train shrieking on the rails. It was human. Carefully, Brian peered around the column.

The platform was almost empty. The tail stood, looking at Brian’s column. Between them stood a freckled man with a baby in a backpack. The noise was the baby bawling, red faced.

The four of them stood for a long time that way. The shadow couldn’t do a thing with a witness standing there. The baby kept screaming. Its face was turning purplish. The freckled father glanced at the man in the camel-hair coat, glanced at Brian. He looked nervous. He could tell something was going on.

Brian stared back at the shadow defiantly. Or at least he hoped he looked defiant. In truth, he was desperately agonizing over how he would lose the man while still dragging his cello with him — trying to dodge through crowds, up and down subway stairs, and along the sidewalks of Brookline.

The baby sobbed on.

The man in the camel-hair coat gave Brian a final, hateful look, then turned and walked off. He trudged up the stairs.

Brian’s shoulders sagged with relief. His cello dipped. He realized that it had been sticking out from behind the column the whole time, completely obvious. He was awful at hiding.

He pulled the cello around the pillar and stood with his back against the concrete, waiting for another train. He tried to shut out the baby’s anguished wail, which blared and boomed in the tunnel.

He was almost relieved when the baby stopped to gag and cough.

But it was at that moment that he heard the shadow talking to people on the stairs. “You can’t go down there,” said the shadow. “Police. Sorry, ma’am. Police. This station is closed. We’re having a situation.”

A woman said, “I have to go pick up salmon.”

“You won’t be leaving from this station, ma’am. We’re engaged in an activity.”

Why, thought Brian, is he shooing people away?

And then he looked at the freckled man, the baby in the backpack. The man was walking toward him, head sinking down between his shoulders. The baby screamed, red, blotchy, and bald.

No one was coming down the stairs. There wouldn’t be any witnesses.

Brian’s heart swung a beat and began to pound.

The baby’s mouth spread wide, too wide for any human mouth. Though it was an infant, it had rows and rows and rows of teeth.

It looked very hungry.

TWO

Brian had to get by the man and the demon baby. He had to get up the steps. He grabbed his cello and then he thought, Wait. I’ll have to leave the cello. This was not easy for him to do. He and the cello had been through a lot together: melancholy sonatas … terrifying recitals. But still, that didn’t mean they had to die together. He left it leaning, darted to the side, dashed for the exit.

The freckled man put out an arm and veered toward him.

Brian saw he wouldn’t make it to the steps. He skidded to a stop and dropped low like he had seen basketball players do. He hovered, waiting to see which way the freckled man would move.

The freckled man was not a human organism. His face was crumpling into something creased and alien, and it was clear that the infant on his back was no separate infant but another head on the same body, a hump, another mouth to feed. The baby was not squinting — it didn’t have eyes. Just that wide, saw-toothed mouth.

The man-infant was, for a moment, poised like Brian, knees bent, hands low. And then it was on all fours. Arms and legs were bending in ways that no human limb could twist without snapping.

The creature was rearing to pounce.

Brian tried to make a break for it. He took a few thudding steps to the left. The monster countered, its infant mouth still screaming and sloppy.

The beast’s father-mouth snarled and snapped. The baby-head, now bloated and distorted, rocked and howled. The monster paced forward. Brian stepped back.

It was now or never. Brian turned and ran past his pillar, past his cello, to a service door in the tunnel. He tugged the handle.

Locked.

The monster had not moved, but smiled a curiously human smile and began to prowl forward, elbows out.

Brian didn’t like the look of those two mouths, nor the gnarled fingers that tapped along the concrete floor.

There was no place to run. There was no more platform.

Brian jumped down onto the tracks. Mice scattered as he hit the sooty gravel.

Farther down the tunnel, he saw the light from the inbound platform. If he could just make it there, there would be people — witnesses — maybe help.

So he ran.

Gravel chiseled at his shoes, spattered behind him. He heard the thunk as the beast threw itself down after him and began to lope forward. He heard it gaining.

Down the tunnel, at the inbound platform, there was not only light, not only the sound of people milling, but music. Brian could hear a man with a guitar, warbling, “You put me high upon a pedestal … so high that I could —”

The monster was at Brian’s side. It was still twenty feet to the music, the light, the crowd. And now the monster was in front of him.

It grinned and lifted one of its emaciated claws. Its clothes were in shreds from its transformation. Its baby-mouth was huge and warping with its cries. The beast was ready to finish him off.

Brian suddenly had an idea. A last chance.

The baby-maw coughed and drooled wet cheese, milk curdled with the blood of some previous victim.

“Uh — uh — okay,” said Brian. “Come on.”

The monster pounced.

And at the same time, Brian hurtled backward, swinging his arms. He straddled the electrified third rail — one foot on either side of it — and thudded back, terrified he’d tumble. He took a chance that the creature wasn’t aware of human ways. He bet that a monster sent by the Thusser wouldn’t know that through the subway’s third rail ran a thousand volts of electricity.

The beast paced toward him as he scrambled away. It swung its heads from si

de to side.

Digging his heels into the black gravel, Brian kept staggering backward.

The monster slipped forward, raising a bony claw to maul him. Brian shrank away — pivoted — felt the claw swipe —

— and miss —

— and hit the rail.

The alien beast’s body arched. The bulging father-eyes blinked once.

The baby-mouth gave a furious yowl.

And then the thing fell and began to spasm on the tracks. Its back arched further. Its feet flailed.

Brian watched in horror.

Then he saw a train was coming — at first, just light on the wall and a barreling racket.

He scampered toward the outbound platform, where he had come from.

He pulled himself up.

The train appeared in the tunnel. Brian was sitting on the yellow strip near the platform’s edge. His whole body still stung with alarm.

As the train pulled into the station, Brian stood up, shaking, next to his instrument case. The doors opened. People trooped out.

And a few seconds later, Brian got on, lugging his cello, and headed to meet Gregory. There was nothing following him now.

Except the knowledge that he was hunted, and that whatever sought him out would not stop until he was dead.

THREE

Many centuries ago, when the people of Europe still dressed in pelts and scavenged like animals, back when queens pulled birds apart with their teeth, and kings lived in wooden shacks they called feasting halls, a race of sublime, elfin creatures dwelled in the hills. These creatures held court in gemmed ballrooms and delighted themselves with subtle games and whispery fantasias played on instruments of silver. They were reasonably fond of the human animal, though the humans tended to smell bad, eat too much, cry about angels, and leave their droppings on the floor. When the human beasts started to multiply, however, many of the elfin race felt there was no longer enough room for their airy castles and subterranean cities in the hills of Europe, and so a party of them set out for the New World, having read that the human population there was more scarce and not so given to delving in the ground and knocking down sacred groves.