Fenrir c-2

M. D. Lachlan

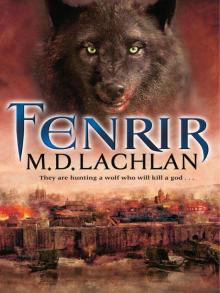

Fenrir

( Craw - 2 )

M. D. Lachlan

M. D. Lachlan

Fenrir

And he caught the dragon, the old serpent, that is the Devil and Satan; and he bound him by a thousand years. And he sent him into deepness, and closed, and marked on him, that he deceive no more the people, till a thousand years be filled. And he sent him into deepness, and closed, and signed, or sealed, upon him, that he deceive no more people, till a thousand years be fulfilled. After these things it behooveth him to be unbound a little time.

THE KING JAMES BIBLE, REVELATION 20: 1-3

When the?sir saw that the Wolf was fully bound, they took the chain that was fast to the fetter, and which is called Thin, and passed it through a great rock — it is called Scream — and fixed the rock deep down into the earth. Then they took a great black boulder and drove it yet deeper into the earth and used the stone for a fastening-pin. The wolf gaped terribly, and thrashed about and strove to bite them; they thrust into his mouth a certain sword: the guards caught in his lower jaw, and the point in the upper; that is his gag. He howls hideously, and slaver runs out of his mouth: that is the river called Van; there he lies till the Weird of the Gods.

THE PROSE EDDA

PART ONE

Sword Age

1

Wolf Night

He had never seen a sight so beautiful as Paris under flame. It was dusk and the smoke lay across the low sun in a long stripe of black like the tail of a dragon, its head dipping to a mouth of fire on the river island town. He looked down from the hill and saw that the towers on the bridges had held: the Franks had repulsed the northern enemy. Though part of one bridge and an abandoned longboat beneath it were on fire, the saffron banners of Count Eudes still flew all around the walls above the water, like little flames themselves answering the dying sun.

Leshii inhaled. There, beneath the smell of the burning wood and the pitch the defenders had hurled down on the invaders was another smell he recognised well. Cremation.

He associated it with the Northmen, with the burning of their dead in their ships. He’d watched them in the aftermath of the battle to take Kiev, pushing the dead rulers Askold and Dir out of the town out onto the lake in a blazing longboat. They’d given them a fine send-off, considering they’d butchered them.

The smell seemed to suck all of the moisture out of his nose and mouth. People had burned down there. He shook his head and made the lightning bolt symbol of his god Perun across his chest with his finger. Warriors, he thought, had too much of the world. If it was ruled by merchants there wouldn’t be half the killing.

He looked at the city. It wasn’t big by his eastern standards but it was wonderfully placed on the Seine to stop the Viking raids getting any further upstream.

The dusk was cold and his breath clouded the air. He would have loved to have gone down to the city and sat by a fire with a mug of Frankish wine.. He found the Franks very relaxed and peaceful — at least when at ease in their own towns — and they were great lovers of silk. He’d always enjoyed Paris with its fascinating houses, square and pale, with arches for entrances and steep pitched roofs of checked tiles. No point letting that thought grow. The idea of warmth only made the cold seem deeper. There would be no shelter that night, beyond his tent. The hillside would be his bed, not an inn in the merchants’ quarters.

He watched as, on the bridge, the defenders beat down the flames. The bridges had been put there primarily to prevent ships coming up the river. They had done their job, along with the other defences the count had built. It was difficult to estimate the size of the Northmen’s army. If they controlled both banks of the river, he put it as massive, at least four thousand men. However, yellow banners spread themselves among the sprawl of meaner houses outside the city too. So perhaps the Danish force was smaller. Big enough, though, easily big enough to overrun any dwellings unprotected by the city walls.

Yet they hadn’t bothered to take them. Clearly, the northerners did not regard those buildings as important. They were moving through to richer and bigger towns along the river. Paris was just an obstacle to overcome and they weren’t going to lose good men fighting over a few huts. Leshii was impressed. Most commanders he knew had very little control over what their troops did once they got in sight of the enemy. This was a disciplined army, not a rabble.

Could he get down to one of those outlying houses, hire a bed there? No. The whole country would be in a terror and he’d be lucky not to be strung up by either side if they saw him.

There were Vikings on both sides of the river, he could tell. Their longships were moored on both banks and their black banners drooped in the still spring air for a fair slice of land about. Leshii gave a shiver when he thought of those banners. He had seen them enough times in the east — ravens and wolves. Such creatures prospered in the Norsemen’s wake. The city would fall, he thought, but it would take a while doing so.

‘She is in there?’ Leshii spoke in Latin, as it was the only language he shared with his companion.

‘It was foreseen.’

‘Good luck getting her out. They won’t welcome a Northman in there.’

‘I won’t ask for their welcome.’

‘Better declare yourself to your people and enter when they enter. They surely will, their army is huge.’

‘They are not my people.’

‘You are a Northman, a Varangian as you are called.’

‘But I am not a Dane.’

‘All Varangians are the same, Chakhlyk. Dane, Norseman, Viking, Norman, Varangian: these are only words for the same thing.’

‘My name is not Chakhlyk.’

‘But your nature is — it means “dry one” in my language. What is a name but what men call you? My mother called me Leshii, but at home they call me Mule. It’s not a name I like but one that fits because I’m always carrying things here and there for one person or another — princes, kings, myself. They call me Mule: my name is Mule. I call you Chakhlyk: your name is Chakhlyk. Names are like destinies, we do not choose them.’

The Northman snorted. It was the first time since they had travelled from the east that Leshii had seen him smile.

Leshii looked at his travel companion, who was more than a mystery to him. He found his presence deeply disquieting and, if the instruction to show him to Paris had not come from Prince Helgi the Prophet himself, he would have found some way of avoiding the trip. Helgi was a Varangian too, the ruler of Ladoga, Novgorod, Kiev and the surrounding lands of the Rus. He had warred as far as Byzantium, nailing his shield to the gates the city closed against him. He was a mighty ruler, and when he commanded his subjects did well to obey.

Leshii had asked the name of this strange man, but Helgi had told him he didn’t have one so he was at liberty to make one up. Chakhlyk then, which was more polite than what he might have chosen. Chakhlyk was tall, even for his race, but unlike many of his kinsmen was dark and thin and wiry, reminding Leshii more of something grown from the earth, a twisted tree perhaps, rather than a human.

Leshii knew everyone who had been to Ladoga, most people in the neighbouring city of Novgorod and a fair few even further down in Kiev, but he had never seen this fellow before. At first he had tried conversation with him. ‘My business is silk, brother; what is your trade?’ The man had said nothing, just looked at him with those intense dark eyes. Leshii had understood when the prince had sent them out without any escort what the man’s trade was. He had understood it when other traders on their route had sat away from them at the fire, when curious farmers had gone creeping back to their homes rather than talk to them, when bandits had watched from the hills but not summoned the courage to come down. His trade was fear. It seeped from him like the musk of an animal.

&nbs

p; Leshii guessed that the wolfman must be one of the northerners’ wild priests, though he had never seen one like him before. The Varangians’ kings were their main holy men but a variety of odd individuals sacrificed to their strange gods at their temples in the woods outside Lagoda. They wore symbols of hammers and swords and, he had heard it rumoured, even real nooses for their very secret ceremonies. This man, though, just wore a strange pebble at his neck on a leather thong. Something was scratched on it, but Leshii had never quite got close enough to see what.

The Northman took off the bag he carried on his back and unrolled something from it.

Leshii, to whom the contents of bags were always an irresistible spark to curiosity, came to see what it was. He recognised it immediately — it was a complete wolfskin, though rather unusual. The fur was coal-black and, even in the dusk, its gloss seemed almost unnatural. It was huge, quite the biggest wolf pelt Leshii had ever seen, and as a trader he had seen a few.

‘It’s a fine skin,’ he said, ‘but I don’t think the townsmen of Paris will be in the mood for business. If you are planning to sleep in it then in such cold as this I, your guide, should be allowed a share.’

The Northman didn’t reply, just walked back into the trees taking the pelt with him.

Now Leshii had nothing to do. He began to feel sorry for himself. He had hoped the rumours of the siege of Paris had been untrue. If Paris was under attack it was likely that other bigger and more important trading centres, such as Rouen, had taken a hit too.

Had he struggled on with his cargo for nothing? He supposed there might be the possibility of finding some takers for his goods in the Viking camp. He went to see to the mules, in two minds whether to take off their burdens there and then or to keep them on in case any stray northerners came up the hill after dark and he had to get away quickly. Perhaps he could sell to the invaders. He had lived under the rule of the Varangians most of his life and understood them. He could do a deal, he thought, if he could persuade them not to hang him in sacrifice to one of their odd gods.

He looked down at the river plain. The longships to the north were withdrawing to the south bank. Something was happening there. The Danes were running away from the bank as if pursued. From the east, casting long shadows behind them, he saw two riders moving across the plain — one leading the other’s horse. The Danes were rushing to greet them. Perhaps they were merchants, he thought, perhaps there was a proper market for his goods after all.

He was cold and he was old, too old for this. He might even have found a way to refuse Helgi and stay in Ladoga had his business been better. Five rough years with cargoes lost to bandits and a silkworm disease in the east had eaten into his savings. Helgi’s offer to buy him a cargo had been too good to refuse. If he could get a decent price for it he would leave the travelling to younger men in future. Too tired to think any more, he untied the bags from the mules. Could he sit down to a fire and some wine? Why not? One more plume of smoke wouldn’t matter in the darkness and, behind the hill, the fire wouldn’t be seen by anyone.

He saw to the animals, laid out his rug, made a fire, drank his wine and ate some dried figs along with a little flat bread and some cheese. Before he knew it he was asleep, and then, under the light of a full and heavy moon, he was awake again. What had woken him? Chanting, an understated mumble of words like the sound of a distant river.

He shivered and stood to find his coat. His head cleared. Never mind the coat, where was his knife? He took it out and looked down at it in the moonlight. It was the one he used to cut silk — sharp, broad-bladed, single-edged and comforting.

The chanting went on in no language of the many he understood. He was faced with a choice: go towards it, ignore it or go away. With a train of six mules there wouldn’t be much sneaking off. The noise was too disquieting to let him sleep and he knew that there was the possibility it was some strange enemy. Better to surprise than be surprised, he thought, and made his way towards the sound.

The trees cut sharp shadows into the moonlit ground, dark lines of ink on a page of silver. Leshii gripped his knife. There was a pale shape sitting thirty paces from him through the trees. He made his way towards it. The chanting stopped. A cloud blew across the moon. Leshii could see nothing. He went forward sightless, groping from tree to tree. And then, at his shoulder, he heard a breath.

He took a pace back and stumbled on a root, falling onto his backside. He looked up and, as the moon turned the edge of a cloud to crystal, it was as if the shadows seemed to coalesce into something approaching a human form. But it wasn’t human because its head was that of a huge wolf.

Leshii shouted out and pushed forward his knife to interpose it between him and the thing that seemed to be drawing in the shadows, taking its substance from them.

‘Do not fear me.’

It was the Chakhlyk, the Northman, his voice hoarse with stress. Leshii squinted into the darkness and saw that it was him, with that huge pelt draped over his shoulders, the head of the wolf above his head, as if it was his own. He had become a wolf, a wolf made of shadows, skin, fear and imagination.

The wind blew the clouds aside for a moment and the tall figure was caught in the stark light of the moon. The pebble at his neck was gone and his face was smeared with something, his hands too, something black and slick. Instinctively Leshii put his hand forward and touched the wolfman’s head. The merchant felt wetness on his fingers. He put them to his lips. Blood.

‘Chakhlyk?’

‘I am a wolf,’ said the Northman. The clouds returned, and it was as if he was a pool of darkness into which all the shadows of the forest poured as streams. Then Leshii was alone in the night.

2

The Confessor

Jehan could smell the plague setting in, the deep note of putrefaction beneath that of the filthy streets, beneath the sour starvation on the people’s breath.

They carried him down from Saint-Germain-des-Pres at night, the smoke of the burned abbey still in his clothes. He felt the cool of the water approaching, the stumble of the monks as they put his pallet onto the boat, the sick rocking that accompanied the journey across. He sensed the tension in the men in the tight silence that they kept, heard the careful movement of the muffled oars, the strokes gentle and few, and then the harsh whisper of a password.

‘Who?’

‘Confessor Jehan. Blind Jehan.’

The gate opened and the perilous part began — the transfer from the little boat onto the narrow step. The brothers tried to keep him on the pallet at first but it was quickly obvious that would be impossible. He solved the problem himself.

‘Carry me,’ he said. ‘Come on, hurry up. I am light enough.’

‘Can you climb on my back, Confessor?’

‘No. I am a cripple, not a monkey — can you not see?’

‘Then how shall I carry you?’

‘In your arms, like a child.’

The men escorting him were new to the monastery — warriors sent from a brotherhood to the south to help Saint-Germain defend against the Northmen, much good that the two of them had done. They were unused to Confessor Jehan and he could feel their uncertainty in the way he was taken from the boat. The warriors had never touched a living saint before.

It was a tight squeeze through the Pilgrims’ Gate. The walls of the city had been built by the Romans nine feet thick. The passage through them on the city’s north side had been cut later, to spare royalty the crush of the market-day crowds. It was not a weakness in the wall but a strength. Any invader breaking in would have to turn his body and sidle into the city, no chance to use a weapon. The passage from the gate was known as Dead Man’s Alley for good reason.

So, though the monk who carried him went carefully, Jehan found himself bumped and scraped into the city.

He was carried up the steps. He heard the gate close behind him, footsteps and murmured questions to his companions. The wet scent of the spring river was replaced by the damp and piss of the tight alley and

the astringent, strangely pleasant note of boiling pitch and hot sand as they reached the top. Clearly, if the Vikings were to try their luck at night by that gate then the defenders were ready for them.

The monk lowered Jehan to his pallet again and he felt himself lifted up. The pallet moved through the narrow lanes. They had come at the dead of night to hide from their enemies but also from their friends. With so many sick in the city, so many desperate souls, the confessor’s progress would have been impossible by day — too many seeking his healing touch.

They came to a halt and Jehan felt himself lowered. A light breeze brought the stench of rot. He had heard that there was nowhere to bury the dead now and that corpses lay out in the streets awaiting a time they could be properly buried. If that was the case, he thought, it would do the people good. It was spiritually useful to confront the reality of death, to see the inevitable end and to think on your sins. He felt sorry for them, nevertheless. It must be hard to lose a loved one and to pass their mortal remains as you went about your business every day.

The confessor knew there was a chance he could be marooned on the island. A section of both banks of the river had held against the Danes, making resupply of the walled city, and expeditions like his own, risky but possible. However, the people were weak and dispirited from nearly four months of struggle. If the Norsemen attacked the city outside the walls, instead of concentrating on the bridges barring their progress upstream, the banks would fall and there would be no resupply, no coming and going even for a small unlit boat in the middle of the night.

‘Father?’

He recognised the voice.

‘Abbot Ebolus.’

‘Thank you for coming.’ The voice was near his ear — the abbot had bent to Jehan’s level. The confessor could smell the sweat of battle on him, the smoke and the blood. Up close, the warrior-monk reeked like a butcher’s shelf. ‘Do you think you can help her?’