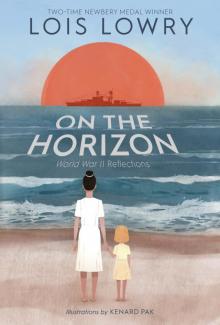

On the Horizon

Lois Lowry

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Part 1. On the Horizon

That Morning

Rainbows

Aloha

She Was There

Leo Amundson

George and Jimmie

Solace

Jake and John Anderson

Birthday

The Beach

The Band

The Musicians

Captain Kidd

James Myers

Silas Wainwright

8:15, December 1941

The Fourth Turret

Child on a Beach

Pearl Harbor

Part 2. Another Horizon

Names

Japanese Morning

The Cloud

Afterward

Takeo

The Red Tricycle

Tram Girls

Sadako Sasaki

Chieko Suetomo

The Tricycle

8:15, August 1945

Hiroshima

Part 3. Beyond the Horizons

Meiji

After That Morning

Bon Odori

Hibakusha

Invisible

The Word For “Hate”

Girl on a Bike

Gaijin

Now

Tomodachi

Author’s Note

Bibliography

Read More from Lois Lowry

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Text copyright © 2020 by Lois Lowry

Illustrations copyright © 2020 by Kenard Pak

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

The illustrations in this book were done in pencil and edited digitally.

Japanese calligraphy on page 66 by Yoriko Ito

Cover design by Whitney Leader-Picone

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lowry, Lois, author. | Pak, Kenard, illustrator.

Title: On the horizon / Lois Lowry ; illustrated by Kenard Pak.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2020] | Audience: Ages: 10–12 | Audience: Grades: 4–6 | Summary: “From two-time Newbery medalist and living legend Lois Lowry comes a moving account of the lives lost in two of WWII’s most infamous events: Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima. With evocative black-and-white illustrations by SCBWI Golden Kite Award winner Kenard Pak.”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019008795 (print) | LCCN 2019980713 (ebook)

ISBN 9780358129400 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358129387 (ebook) | ISBN: 978-0-358-35476-5 (signed edition)

Subjects: LCSH: Lowry, Lois—Childhood and youth—Juvenile literature. | World War, 1939–1945—Casualties—Juvenile literature. | Pearl Harbor (Hawaii), Attack on, 1941—Juvenile literature. | World War, 1939–1945—Hawaii—Juvenile literature. | World War, 1939–1945—Japan—Hiroshima-shi—Juvenile literature. | World War, 1939–1945—Personal narratives, American—Juvenile literature. | Hiroshima-shi (Japan)—History—Bombardment, 1945—Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC D743.7 .L69 2020 (print) | LCC D743.7 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/25219540922—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019008795

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980713

v1.0320

For Howard, with love

PART 1.

On the Horizon

On December 7, 1941, early on a Sunday morning, Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii. Most of the United States Pacific Fleet was moored there. Tremendous damage was inflicted, and the battleship Arizona sank within minutes, with a loss of 1,177 men.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor that day was the beginning, for the United States, of World War II.

I was born in Honolulu in 1937. Years later, as I watched a home movie taken by my father in 1940, I realized that as I played on the beach at Waikiki, USS Arizona could be seen through mist in the background, on the horizon.

That Morning

They had named the battleships for states:

Arizona

Pennsylvania

West Virginia

Nevada

Oklahoma

Tennessee

California

Maryland

They called them “she”

as if they were women

(gray metal women),

and they were all there that morning

in what they called Battleship Row.

Their places

(the places of the gray metal women)

were called berths.

Arizona was at berth F-7.

On either side, her nurturing sisters:

Nevada

and Tennessee.

The sisters, wounded, survived.

But Arizona, her massive body sheared,

slipped down. She disappeared.

Rainbows

It was an island of rainbows.

My mother said that color arced across the sky

on the spring day when I was born.

On the island of rainbows,

my bare feet slipping in sand,

I learned to walk.

And to talk:

My Hawaiian nursemaid

taught me her words, with their soft vowels:

humuhumunukunukuāpua`a

the name of a little fish!

It made me laugh, to say it.

We laughed together.

Ānuenue meant “rainbow.”

Were there rainbows that morning?

I suppose there must have been:

bright colors, as the planes came in.

Aloha

My grandmother visited.

She had come by train across the broad land

from her home in Wisconsin, and then by ship.

We met her and heaped wreaths

of plumeria around her neck.

“Aloha,” we said to her.

Welcome. Hello.

I called her Nonny.

She took me down by the ocean.

The sea moved in a blue-green rhythm, soft against the sand.

We played there, she and I, with a small shovel,

and laughed when the breeze caught my bonnet

and lifted it from my blond hair.

We played and giggled: calm, serene.

And there behind us—slow, unseen—

Arizona, great gray tomb,

moved, majestic, toward her doom.

She Was There

We never saw the ship.

But she was there.

She was moving slowly

on the horizon, shrouded in the mist

that separated skies from seas

while we laughed, unknowing, in the breeze.

She carried more than

twelve hundred men

on deck, or working down below.

We didn’t look up. We didn’t know.

Leo Amundson

Leo was just seventeen.

He’d enlisted in July.

The U.S. Marines! He must have been proud.

And his folks, too: Scandinavian stock.

Immigrants to Wisconsin, like my own grandparents.

Leo was from La Crosse. My father was born there.

My Nonny had come from La Crosse by train.

Had she known Leo’s parents?

Had she nodded to Mrs. Amundson on the street?

Nonny and I played on the beach in the sunshine.

On the horizon, the boy from La Crosse

(just seventeen),

service number 309872,

was on the ship. We never knew.

George and Jimmie

George and Jimmie Bromley,

brothers from Tacoma,

handsome boys with curly hair.

(Jimmie was the older, but not by much.)

There were thirty-seven sets of brothers aboard

(one set was twins).

And a father and son,

Texans: Thomas Free and his

seventeen-year-old boy, William.

Both gone. Both lost.

They found George Bromley’s body.

Not Jimmie’s, though.

Solace

The hospital ships had names that spoke of need:

Comfort

Hope

Solace

Mercy

Refuge

They carried the wounded and ill.

That morning, Solace was moored near the Arizona.

She sent her launches and stretchers across.

The harbor had a film of burning oil.

Scorched men were pulled one by one from the flames

and taken to Solace.

Jake and John Anderson

John Anderson survived the attack.

He’d been preparing for church.

Rescued, he asked to go back.

He begged to return, to search.

He was burned and bleeding.

“My brother’s still there,” he said,

distraught, desperate, and pleading.

“Jake’s there! I know he’s not dead!”

But one would die, and one live on.

Identical twins. Jake and John.

Birthday

Everett Reid turned twenty-four

December sixth, the day before.

He held the rank machinist’s mate.

He’d celebrated, stayed out late

with friends; they’d danced and sung.

He lived ashore. He’d married young.

In the morning, when he woke,

he heard the sirens, saw the smoke.

He’d remember all his life

the hasty parting from his wife,

her quick and terrified embrace,

his frantic journey to the base.

His birthdays, though, for many years

brought no joy. Just grief. Just tears.

The Beach

The morning beach was deserted.

We were alone, Nonny and me

(and Daddy, his camera whirring).

I tiptoed, pranced, and flirted

with waves. Just we three

and empty beach. Nothing stirring.

And if we’d looked? And been alerted

to a gray ship at the edge of the sea?

The mist would still have been there, blurring

the shape of a ship moving slowly.

Now, years later, it seems holy.

The Band

NBU 22. That’s what it was called:

Navy Band Unit 22. The Arizona band.

That morning—it was not yet eight—

they were on deck, about to play.

(Their music raised the flag each day.)

When the alert came,

they ran to their battle station—

they called it the black powder room.

Their job was to pass ammunition

to the gunners. But the black powder exploded.

Twenty-one young men, prepared

for morning colors. Not one was spared.

All the high-stepping boys

who’d marched at high school

football games, once; who’d enlisted;

now, with their instruments, lay twisted.

The Musicians

Neal Radford: At twenty-six,

Neal was the oldest among

the musicians. The others

were all so very young,

like Alexander Nadel—don’t forget

he went to Juilliard! But was still

just twenty. He played cornet.

So did the youngest; that was Bill

McCary, southern boy, seventeen.

An only child from Birmingham,

Billy was eager, bright, and keen

to give his all for Uncle Sam.

Music was their main pursuit.

Curtis Haas—they called him Curt—

played clarinet, tenor sax, and flute.

A handsome kid: a clown, a flirt.

Each band member was, like him,

such a source of family pride.

Curt was young, hardworking, trim;

twenty-one the day he died.

Back home each one had friends they missed,

dogs they’d raised, and girls they’d kissed;

childhood rooms with model planes,

boyhood bikes with rusted chains;

moms and dads and baseball teams,

and dreams—each one of them had dreams.

Captain Kidd

It sounds like the name of a pirate.

Nonny told me stories of pirates,

of trolls, and dragons, and kings.

Imaginary things.

He was not an imaginary hero.

He was Captain Isaac Campbell Kidd,

commanding officer of USS Arizona.

His friends called him Cap.

When he was made commander

of the entire Battleship Division,

he became an admiral.

Admiral Kidd ran to the bridge

that morning in December.

His Naval Academy ring

was found melted and fused to the mast.

It is not an imaginary thing,

a symbol of devotion so vast.

James Myers

James was from Missouri

and had two brothers.

The older boy had died in France

in World War I.

The youngest (out in a field,

bringing in the cows, when a storm struck)

was killed by lightning.

He was fifteen.

So James was left.

He married, and had two sons himself.

But his wife died young, and

the little boys, Jimmy and Gordon,

went to live with their grandma in Seattle.

It was the other grandma,

widowed Mary Myers, in Missouri,

who opened the telegram with dread.