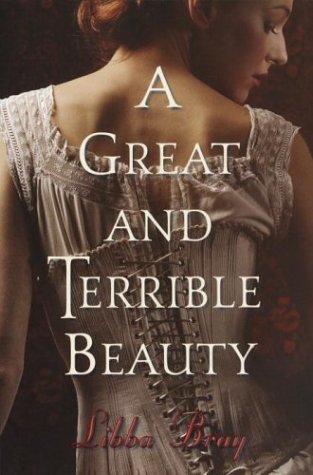

A Great and Terrible Beauty

Libba Bray

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

London, England. Two months later.

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

About the Author

Copyright Page

For Barry and Josh

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book couldn’t have been written without the sage advice and welcome help of many people. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the following:

The Trinity of Fabulousness: my agent, Barry Goldblatt; my editor, Wendy Loggia; and my publisher, Beverly Horowitz.

Trish Parcell Watts, who created such a delicious cover; Emily Jacobs, for her invaluable input; and Barbara Perris, copy editor extraordinaire.

The tireless staffs of the British Library and the London Transport Museum, especially Suzanne Raynor.

Professor Sally Mitchell, Temple University, who gave me some great leads in my research, for which I am very much indebted. For anyone interested in the Victorian age, I strongly recommend her books, The New Girl and Daily Life in Victorian England.

The Victorian Web, Brown University.

The supportive writing communities of YAWriter and Manhattan Writers Coalition.

The generous, big-hearted Schrobsdorff family: Mary Ann, for the wonderful resources and actual Victorian clothes for study; Ingalisa, for the terrific jacket photo; and the ever-great Susanna, for cheering, baby-sitting, and correcting my terrible French.

Françoise Bui, for correcting even more of my terrible French.

Franny Billingsley, who read the first draft and gave me ten pages of in-depth insight.

Angela Johnson, for telling me to write the book I needed to write.

Laurie Allee, for helping me find the heart of it.

My friends and family, who cheered me on and excused me from returning phone calls, checking the expiration on the milk, and getting birthday cards in the mail on time because (sigh) “she’s writing that book.”

And especially Josh, for being so patient when Mommy had to finish “just one last thing.”

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving through a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot . . .

• • •

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often through the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot;

Or when the Moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed.

“I am half sick of shadows,” said

The Lady of Shalott.

• • •

And down the river’s dim expanse

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance—

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

—from “The Lady of Shalott” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

CHAPTER ONE

JUNE 21, 1895

Bombay, India

“PLEASE TELL ME THAT’S NOT GOING TO BE PART OF MY birthday dinner this evening.”

I am staring into the hissing face of a cobra. A surprisingly pink tongue slithers in and out of a cruel mouth while an Indian man whose eyes are the blue of blindness inclines his head toward my mother and explains in Hindi that cobras make very good eating.

My mother reaches out a white-gloved finger to stroke the snake’s back. “What do you think, Gemma? Now that you’re sixteen, will you be dining on cobra?”

The slithery thing makes me shudder. “I think not, thank you.”

The old, blind Indian man smiles toothlessly and brings the cobra closer. It’s enough to send me reeling back where I bump into a wooden stand filled with little statues of Indian deities. One of the statues, a woman who is all arms with a face bent on terror, falls to the ground. Kali, the destroyer. Lately, Mother has accused me of keeping her as my unofficial patron saint. Lately, Mother and I haven’t been getting on very well. She claims it’s because I’ve reached an impossible age. I state emphatically to anyone who will listen that it’s all because she refuses to take me to London.

“I hear in London, you don’t have to defang your meals first,” I say. We’re moving past the cobra man and into the throng of people crowding every inch of Bombay’s frenzied marketplace. Mother doesn’t answer but waves away an organ-grinder and his monkey. It’s unbearably hot. Beneath my cotton dress and crinolines, sweat streaks down my body. The flies—my most ardent admirers—dart about my face. I swat at one of the little winged beasts, but it escapes and I can almost swear I hear it mocking me. My misery is reaching epidemic proportions.

Overhead, the clouds are thick and dark, giving warning that this is monsoon season, when floods of rain could fall from the sky in a matter of minutes. In the dusty bazaar the turbaned men chatter and squawk and bargain, lifting brightly colored silks toward us with brown, sunbaked hands. Everywhere there are carts lined with straw baskets offering every sort of ware and edible—thin, coppery vases; wooden boxes carved into intricate flower designs; and mangos ripening in the heat.

“How much farther to Mrs. Talbot’s new house? Couldn’t we please take a carriage?” I ask with what I hope is a noticeable annoyance.

“It’s a nice day for a walk. And I’ll thank you to keep a civil tone.”

My annoyance has indeed been noted.

Sarita, our long-suffering housekeeper, offers pomegranates in her leathery hand. “Memsahib, these are very nice. Perhaps we will take them to your father, yes?”

If I were a good daughter, I’d bring some to my f

ather, watch his blue eyes twinkle as he slices open the rich, red fruit, then eats the tiny seeds with a silver spoon just like a proper British gentleman.

“He’ll only stain his white suit,” I grumble. My mother starts to say something to me, thinks better of it, sighs—as usual. We used to go everywhere together, my mother and I—visiting ancient temples, exploring local customs, watching Hindu festivals, staying up late to see the streets bloom with candlelight. Now, she barely takes me on social calls. It’s as if I’m a leper without a colony.

“He will stain his suit. He always does,” I mumble in my defense, though no one is paying me a bit of attention except for the organ-grinder and his monkey. They’re following my every step, hoping to amuse me for money. The high lace collar of my dress is soaked with perspiration. I long for the cool, lush green of England, which I’ve only read about in my grandmother’s letters. Letters filled with gossip about tea dances and balls and who has scandalized whom half a world away, while I am stranded in boring, dusty India watching an organ-grinder’s monkey do a juggling trick with dates, the same trick he’s been performing for a year.

“Look at the monkey, memsahib. How adorable he is!” Sarita says this as if I were still three and clinging to the bottoms of her sari skirts. No one seems to understand that I am fully sixteen and want, no, need to be in London, where I can be close to the museums and the balls and men who are older than six and younger than sixty.

“Sarita, that monkey is a trained thief who will be begging for your wages in a moment,” I say with a sigh. As if on cue, the furry urchin scrambles up and sits on my shoulder with his palm outstretched. “How would you like to end up in a birthday stew?” I tell him through clenched teeth. The monkey hisses. Mother grimaces at my ill manners and drops a coin in its owner’s cup. The monkey grins triumphantly and leaps across my head before running away.

A vendor holds out a carved mask with snarling teeth and elephant ears. Without a word, Mother places it over her face. “Find me if you can,” she says. It’s a game she’s played with me since I could walk—a bit of hide-and-seek meant to make me smile. A child’s game.

“I see only my mother,” I say, bored. “Same teeth. Same ears.”

Mother gives the mask back to the vendor. I’ve hit her vanity, her weak point.

“And I see that turning sixteen is not very becoming to my daughter,” she says.

“Yes, I am sixteen. Sixteen. An age at which most decent girls have been sent for schooling in London.” I give the word decent an extra push, hoping to appeal to some maternal sense of shame and propriety.

“This looks a bit on the green side, I think.” She’s peering intently at a mango. Her fruit inspection is all-consuming.

“No one tried to keep Tom imprisoned in Bombay,” I say, invoking my brother’s name as a last resort. “He’s had four whole years there! And now he’s starting at university.”

“It’s different for men.”

“It’s not fair. I’ll never have a season. I’ll end up a spinster with hundreds of cats who all drink milk from china bowls.” I’m whining. It’s unattractive, but I find I’m powerless to stop.

“I see,” Mother says, finally. “Would you like to be paraded around the ballrooms of London society like some prize horse there to have its breeding capabilities evaluated? Would you still think London was so charming when you were the subject of cruel gossip for the slightest infraction of the rules? London’s not as idyllic as your grandmother’s letters make it out to be.”

“I wouldn’t know. I’ve never seen it.”

“Gemma . . .” Mother’s tone is all warning even as her smile is constant for the Indians. Mustn’t let them think we British ladies are so petty as to indulge in arguments on the streets. We only discuss the weather, and when the weather is bad, we pretend not to notice.

Sarita chuckles nervously. “How is it that memsahib is now a young lady? It seems only yesterday you were in the nursery. Oh, look, dates! Your favorite.” She breaks into a gap-toothed smile that makes every deeply etched wrinkle in her face come alive. It’s hot and I suddenly want to scream, to run away from everything and everyone I’ve ever known.

“Those dates are probably rotting on the inside. Just like India.”

“Gemma, that will be quite enough.” Mother fixes me with her glass-green eyes. Penetrating and wise, people call them. I have the same large, upturned green eyes. The Indians say they are unsettling, disturbing. Like being watched by a ghost. Sarita smiles down at her feet, keeps her hands busy adjusting her brown sari. I feel a tinge of guilt for saying such a nasty thing about her home. Our home, though I don’t really feel at home anywhere these days.

“Memsahib, you do not want to go to London. It is gray and cold and there is no ghee for bread. You wouldn’t like it.”

A train screams into the depot down near the glittering bay. Bombay. Good bay, it means, though I can’t think of anything good about it right now. A dark plume of smoke from the train stretches up, touching the heavy clouds. Mother watches it rise.

“Yes, cold and gray.” She places a hand on her throat, fingers the necklace hanging there, a small silver medallion of an all-seeing eye atop a crescent moon. A gift from a villager, Mother said. Her good-luck charm. I’ve never seen her without it.

Sarita puts a hand on Mother’s arm. “Time to go, memsahib.”

Mother pulls her gaze away from the train, drops her hand from her necklace. “Yes. Come. We’ll have a lovely time at Mrs. Talbot’s. I’m sure she’ll have lovely cakes just for your birthday—”

A man in a white turban and thick black traveling cloak stumbles into her from behind, bumping her hard.

“A thousand pardons, honorable lady.” He smiles, offers a deep bow to excuse his rudeness. When he does, he reveals a young man behind him wearing the same sort of strange cloak. For a moment, the young man and I lock eyes. He isn’t much older than I am, probably seventeen if a day, with brown skin, a full mouth, and the longest eyelashes I have ever seen. I know I’m not supposed to find Indian men attractive, but I don’t see many young men and I find I’m blushing in spite of myself. He breaks our gaze and cranes his neck to see over the hordes.

“You should be more careful,” Sarita barks at the older man, threatening him with a blow from her arm. “You better not be a thief or you will be punished.”

“No, no, memsahib, only I am terribly clumsy.” He drops his smile and with it the cheerful simpleton routine. He whispers low to my mother in perfectly accented English. “Circe is near.”

It makes no sense to me, just the ramblings of a very clever thief said to distract us. I start to say as much to my mother but the look of sheer panic on her face stops me cold. Her eyes are wild as she whips around and scans the crowded streets like she’s looking for a lost child.

“What is it? What’s the matter?” I ask.

The men are suddenly gone. They’ve disappeared into the moving crowd, leaving only their footprints in the dust. “What did that man say to you?”

My mother’s voice is edged in steel. “It’s nothing. He was obviously deranged. The streets are not safe these days.” I have never heard my mother sound this way. So hard. So afraid. “Gemma, I think it’s best if I go to Mrs. Talbot’s alone.”

“But—but what about the cake?” It’s a ridiculous thing to say, but it’s my birthday and while I don’t want to spend it in Mrs. Talbot’s sitting room, I certainly don’t want to waste the day alone at home, all because some black-cloaked madman and his cohort have spooked my mother.

Mother pulls her shawl tightly about her shoulders. “We’ll have cake later. . . .”

“But you promised—”

“Yes, well, that was before . . .” She trails off.

“Before what?”

“Before you vexed me so! Really, Gemma, you are in no humor for a visit today. Sarita will see you back.”

“I’m in a fine humor,” I protest, sounding anything but.

&nbs

p; “No, you are not!” Mother’s green eyes find mine. There is something there I’ve never seen before. A vast and terrifying anger that stops my breath. Quick as it comes on her, it’s gone and she is Mother again. “You’re overtired and need some rest. Tonight, we’ll celebrate and I’ll let you drink some champagne.”

I’ll let you drink some champagne. It’s not a promise—it’s an excuse to get rid of me. There was a time when we did everything together, and now, we can’t even walk through the bazaar without sniping at each other. I am an embarrassment and a disappointment. A daughter she does not want to take anywhere, not London or even the home of an old crone who makes weak tea.

The train’s whistle shrieks again, making her jump.

“Here, I’ll let you wear my necklace, hmmm? Go on, wear it. I know you’ve always admired it.”

I stand, mute, allowing her to adorn me in a necklace I have indeed always wanted, but now it weighs me down, a shiny, hateful thing. A bribe. Mother gives another quick glance to the dusty marketplace before letting her green eyes settle on mine.

“There. You look . . . all grown up.” She presses her gloved hand to my cheek, holds it there as if to memorize it with her fingers. “I’ll see you at home.”

I don’t want anyone to notice the tears that are pooling in my eyes, so I try to think of the wickedest thing I can say and then it’s on my lips as I bolt from the marketplace.

“I don’t care if you come home at all.”

CHAPTER TWO

I’M RUNNING AWAY THROUGH THRONGS OF VENDORS and beggar children and foul-smelling camels, narrowly missing two men carrying saris that hang from a piece of rope attached to two poles at either end. I dart off down a narrow side street, following the twisting, turning alleys till I have to stop and catch my breath. Hot tears spill down my cheeks. I let myself cry now that there is no one around to see me.

God save me from a woman’s tears, for I’ve no strength against them. That’s what my father would say if he were here now. My father with his twinkling eyes and bushy mustache, his booming laugh when I please him and far-off gaze—as if I don’t exist—when I’ve been less than a lady. I can’t imagine he’ll be terribly happy when he hears how I’ve behaved. Saying nasty things and storming off isn’t the sort of behavior that’s likely to win a girl’s case for going to London. My stomach aches at the thought of it all. What was I thinking?