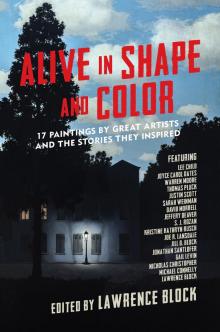

Alive in Shape and Color

Lawrence Block

Office Girls by Raphael Soyer

CONTENTS

FOREWORD: BEFORE WE BEGIN . . .

Lawrence Block

SAFETY RULES

Jill D. Block

PIERRE, LUCIEN, AND ME

Lee Child

GIRL WITH A FAN

Nicholas Christopher

THE THIRD PANEL

Michael Connelly

A SIGNIFICANT FIND

Jeffery Deaver

CHARLIE THE BARBER

Joe R. Lansdale

AFTER GEORGIA O’KEEFFE’S FLOWER

Gail Levin

AMPURDAN

Warren Moore

ORANGE IS FOR ANGUISH, BLUE FOR INSANITY

David Morrell

LES BEAUX JOURS

Joyce Carol Oates

TRUTH COMES OUT OF HER WELL TO SHAME MANKIND

Thomas Pluck

THE GREAT WAVE

S. J. Rozan

THINKERS

Kristine Kathryn Rusch

GASLIGHT

Jonathan Santlofer

BLOOD IN THE SUN

Justin Scott

THE BIG TOWN

Sarah Weinman

LOOKING FOR DAVID

Lawrence Block

PERMISSIONS

FOREWORD

BEFORE WE BEGIN . . .

Here, Gentle Reader, is the foreword as I initially wrote it:

Months before the December publication of In Sunlight or in Shadow: Stories Inspired by the Paintings of Edward Hopper, it had already become clear that the book was destined for success. The pantheon of contributors had turned in a stunning array of stories, and the huge in-house enthusiasm at Pegasus Books guaranteed the book would be well published.

So what would I do for an encore?

I considered—and quickly ruled out—putting together the mixture as before, another anthology of Hopper-inspired stories. The man left us a large body of work, and one could point to any number of paintings as likely to evoke stories as the ones already chosen, but it was clear to me that one trip to that well was enough.

So what other artist might stand in for Edward Hopper in a second volume?

No end of names came up, and not one of them struck me as promising. In each instance, one could imagine a story flowing out of a painting by the proposed artist. Andrew Wyeth, Piet Mondrian, Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko—any of these masters, figurative or abstract, might inspire a single intriguing story. But a whole book’s worth?

I couldn’t see it.

And then the penny dropped. Perhaps a whole roomful of artists could do what a single artist could not.

Seventeen writers producing seventeen stories based on seventeen paintings—each by a different artist.

Alive in Shape and Color.

I didn’t like the title quite as much as In Sunlight or in Shadow—and still don’t, I have to admit. But it would do to get us started.

I took a deep breath, poured myself a cup of coffee, and began drafting an email to potential contributors.

An invitation to contribute to an anthology is an honor, right?

Well, of course it is. And yet I find myself thinking of the visitor who somehow aroused the ire of the local citizenry, some of whom had expressed their displeasure by tarring and feathering the fellow and riding him out of town on a rail.

“But for the honor of the occasion,” he reported, “I’d have preferred leaving town in a more conventional fashion.”

The honor of an anthology invitation brings its own tar and feathers. One has to write something, and the cash return for one’s time and effort is essentially token payment. It’s always been clear to me that to ask someone for a story is to ask that person for a favor.

Sometimes, of course, it all redounds to the writer’s benefit. When I look back at the stories I’ve written for other people’s anthologies, I have much to be grateful for. A couple of stories about a cheerfully homicidal young woman, all written almost grudgingly for friends of mine compiling anthologies, led to a novel, Getting Off. A short story I’d long ago promised for a collection of private eye stories revived Matthew Scudder when I’d assumed I was done writing about him. (The story, “By the Dawn’s Early Light,” was my first sale to Playboy, won me my first Edgar Award, grew into When the Sacred Ginmill Closes, and led over the years to a eight more short stories and a dozen more novels about Mr. Scudder.)

So I can’t say I regret those anthology invitations I’ve received. Still, I issue them diffidently, knowing that they’re always, to some extent, an imposition.

In this instance, I knew where to start. I invited all sixteen ISOIS contributors. They’d been a pleasure to work with, and their stories were superb—and I could only hope that at least a few of them would re-up for another tour of duty.

Megan Abbott had to pass, explaining she had way too much work on her plate. Stephen King, who’d surprised me by letting his love for Hopper lure him into ISOIS—and whose story won him an Edgar nomination—was able to resist this time around. Robert Olen Butler liked the idea of Alive in Shape and Color (which I think I’ll call AISAC for the rest of this introduction); he chose an artist and a painting, then had to bow out when he learned his publisher had committed him to a lengthy book tour that ate up all his time.

But everybody else accepted.

Now I have to tell you that this flat-out astonished me. I sent out a few more invitations, to David Morrell, Thomas Pluck, S. J. Rozan, and Sarah Weinman. And they accepted, too.

All the stories for ISOIS were new, specifically written for the book, and AISAC was similarly conceived. But David Morrell responded to my invitation by stating that he not only liked the premise but that he’d written the story thirty years ago. He sent along “Orange Is for Anguish, Blue for Insanity,” and it wasn’t hard to see what he meant. (It was just as easy to see why it had won a Bram Stoker Award when it was published.)

So the possibility exists that a few of you may have read David’s story before. I don’t think you’ll mind reading it again.

And you could think of it as a bonus, because we’d have eighteen stories this time around, one more than ISOIS. I didn’t see that as a problem, and neither did the good folks at Pegasus.

Eighteen stories? Um, better make that sixteen.

One thing to know about writing is that it doesn’t always work out the way you’d hoped. It’s a rare anthology to which a writer doesn’t fail to deliver a promised story.

This happened with ISOIS. One writer picked a painting and agreed to write a story, and an onslaught of personal problems made work of any sort out of the question. By the time he let us know his story was just not going to happen, we’d already acquired reproduction rights to his chosen painting, Cape Cod Morning. If we couldn’t have the story, at least we could have the painting—and used it as a bonus frontispiece for the book.

This time around, Craig Ferguson found himself unable to deliver. He’d picked a Picasso painting, but the story never came, and his own schedule grew impossibly demanding, with the added time commitment of a new show on SiriusXM radio. He apologized profusely and said he hoped I could understand.

I understood all too well.

Because I too found myself unable to deliver a story.

I’d picked a painting very early on, around the time I was readying my letters of invitation. My wife and I were at a portrait show at the Whitney in New York City, and an oil by Raphael Soyer stopped me in my tracks. I’d never seen it before, knew next to nothing about the artist, and figured it was as perfect a source of fictional inspiration as anything of Hopper’s.

Eventually I got around a thousand words written. But I didn’t like what I�

�d done, nor did I see where to go with it.

Now, I sold my first story in 1957, so I’ve been doing this for sixty years. And I’ve been getting the message lately that it may be something I can’t do anymore. A few years ago it seemed to me that I might be ready to stop writing novels, and while I’ve turned out a book or two since then, I don’t expect to do another. There have been a few short stories and novellas in recent years, and there may be more in what time I have left—but there may be not.

And that’s okay.

If I’d promised the Soyer-inspired story for someone else’s anthology, I’d have long since sent regrets and apologies. But it seemed unpardonable for me to bow out of my own book, and so I banged my head against that particular wall longer than I needed to. Eventually it dawned on me that a book with such fine stories by so distinguished a list of contributors could make its way in the world without a story of mine.

And just because I’d failed to deliver the story didn’t mean you’d have to make do without the painting. Even as Cape Cod Morning functioned admirably as the frontispiece illustration for In Sunlight or in Shadow, so does The Office Girls serve beautifully in that capacity in Alive in Shape and Color. And, as before, I’ll extend an invitation to y’all. Feel free to come up with a story of your own based on Raphael Soyer’s evocative painting. Dream it up—and, if you’re so inclined, write it down.

But don’t send it to me. I’m done here.

And that would have been that, but for an email from Warren Moore, whose Salvador Dali–inspired story is one of the special treats awaiting you. He reminded me that I had in fact published a story twenty years ago that fit AISAC’s requirements quite comfortably. “Looking for David” grew out of my own teenage exposure to a copy of Michelangelo’s statue in Buffalo’s Delaware Park, the recollection triggered by the sight of the original on a 1995 visit to Florence. Matthew Scudder’s in Florence with his wife, Elaine, when a chance encounter with the principal in an old case fills him in on what Paul Harvey used to call “the end of the story”—a story that begins in Buffalo, plays out in New York, and winds up on the banks of the Arno.

A perfect fit for the book, but could AISAC include a second previously published story? I could argue the case either way, so I handed off the decision to Claiborne Hancock at Pegasus, who didn’t hesitate to vote aye. And so AISAC has seventeen stories after all, with Michelangelo’s David joining Rodin’s The Thinker in the sculpture gallery.

But we’ve kept Raphael Soyer’s The Office Girls as a frontispiece, a bonus painting that may inspire you as it didn’t quite manage to inspire me.

—Lawrence Block

JILL D. BLOCK lives in New York City, where she is a writer and an attorney, but not always in that order. Her writing is inspired by the world around her—including, in this case, Art Frahm’s Remember All the Safety Rules, which hangs in her apartment. Her legal work, on the other hand, is inspired by a fear of being fired.

She has had short stories published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and in the anthologies Dark City Lights and In Sunlight or in Shadow. She is coming perilously close to finishing her first novel (which, she acknowledges, will be her only novel unless she writes a second).

Remember All the Safety Rules by Art Frahm

SAFETY RULES

BY JILL D. BLOCK

DAY ONE

This was my third time, and I knew exactly what to expect. I got downtown early, so I had time to stop at Starbucks when I got off the subway. I was upstairs, in the appointed room, at 8:55. I found a seat, took out my magazine, flipped past the fashion ads, and was already pretty well into Graydon Carter’s piece on Trump by the time things got started. The lady told us to tear our cards along the perforated fold, and after she collected the bottom piece, she turned on the instructional video.

I wasn’t at all surprised when a court officer came into the room, about thirty minutes after the video ended, to call for the first group. I knew the drill—twenty or twenty-five of us would be taken up to a courtroom where they’d be selecting a jury. Everyone else would stay here, and other groups would be called for throughout the day and maybe into tomorrow. Three days tops, and I’d have done my civic duty. I hoped that I would be called in this first group—early in, early out. Maybe I’d even have time to look for boots before I headed back uptown.

I did that thing I do, keeping count as he called out names. He read loudly, with the bored authority of a man with a badge, from the stack of cards he was holding, struggling now and then with the pronunciation. I stopped counting when I got to eighty-five and he kept going. I looked around the room—six chairs per row on each side of the center aisle and what looked to be about twenty-five rows. Not every seat had been filled, but it was pretty close. So there were maybe 250 of us? 260? I was trying to do a rough count of how many people were still seated when I heard my name. I put my magazine in my bag, picked up my empty coffee cup, and stepped into the crowd that was making its way toward the door at the back of the room and out into the hallway. The clerk continued to call out names.

It’s funny what happens when the rules change. I had walked in less than an hour earlier, feeling like I owned the place, knowing exactly where to go, what to do, what to expect. Jury duty, yeah, yeah. Maybe I can find a place to get a manicure during the lunch break. And then, there I was, just as lost as everyone else, awaiting instructions and following the crowd into the unknown.

“So that should be everyone.” The clerk kept talking as he moved through the crowd. “If you didn’t hear your name, check the postcard you received in the mail that told you to come here today. If your postcard says September 27, 2016, and room 311, you are in the right place, and you are coming with me. If your postcard says anything other than September 27, 2016, and room 311, you are in the wrong place. If you are in the wrong place, you need to go to the central clerk’s office, room 355. Everyone else, we are going to the ninth floor, part forty-two. Please follow me.”

It took more than forty-five minutes to get us all upstairs and into the courtroom. We were like a class of unruly kindergarteners. We filled all the seats, and there were people standing along the sides and at the back of the room. The judge introduced himself, apologized for there not being enough seats, and thanked us for being there. He introduced the prosecuting attorneys, the defense attorneys, and the defendant, and explained that we were the group from which the attorneys would be selecting a jury of twelve. Why so many people? Well, he explained, the trial is expected to go for four months. Four days a week, ten to five, through January. A collective gasp was followed by a din of whispered conversations. He let us settle down, and then he talked a little bit about how the jury system works. He said that he recognized the sacrifice that each of us had made just by coming in today, not to mention what would be required of the jurors who were selected to serve on this case. Then he asked us to take a few minutes to think, to reflect, to determine, based solely on the schedule he had described, if we would not be able to serve on this jury. He was good. He made you feel like you owed him something, like you really needed to dig deep, to find a way to give of yourself in support of this very fundamental tenet of our legal system. Like if you said you couldn’t do it, you would be letting him down. He said that if we thought we could do it, we were to take a questionnaire from the clerk, go out into the hall and fill it out, then give it back to the clerk when we were done and come back on Friday. If we thought we could not, we were to have a seat. He and the attorneys would meet privately with each of those who stayed, one at a time.

I took a seat.

I spent the rest of the day bored out of my head, with no electronics permitted in the courtroom. It was freezing in there. I kept myself busy watching how they lined people up, as if understanding the system would give me some control over it. They had five people get up at a time, going in order from where we were sitting on the benches. They would have the next five come up when there was one person left on line, waiting ou

tside the closed door. I tried to keep track of how many people ended up taking a questionnaire after they came out from having their private conversation, and how many were given back their card, told to go back to the room we’d started in, presumably to be dismissed. There were seven people left ahead of me when they sent us to lunch and told us to be back at two fifteen. When I got back, I was behind someone who had apparently never been through a metal detector before (“What? I need to take off my belt?”), so I was one of the last people to get back into the courtroom. Instead of there being seven people ahead of me, I was now sitting in the back row, with only four people behind me. All afternoon, it was more of the same, more sitting, more waiting. And then, finally, it was my turn to go in. The judge introduced himself and the lawyers again, and I introduced myself. I explained to them that my job made this impossible for me. That my position at the bank requires redundancy, that there always needs to be someone there who does what I do. They asked how many of us there are, who was covering for me that day, and what happens when one of us gets sick or goes on vacation. I wondered what I should have said instead, if they would have asked me for proof if I’d said I had life-saving surgery scheduled. The judge thanked me for my time and told me to fill out a questionnaire and be back on Friday.

DAY TWO

We’d been told to report to a bigger courtroom, but they were still a couple of seats short for everyone who came back on Friday. It turned out that my group from Tuesday was the second group—they’d done the same thing with another group two weeks before, and this was day two for everyone who had filled out a questionnaire. The judge began by telling us that we were the group from whom the attorneys would be selecting a jury for the 1978 kidnapping and murder of Milo Richter. I felt myself take a breath. Micheline! All of a sudden, it made perfect sense. I was there for a reason. The judge explained that familiarity with the case was not a reason anyone would be dismissed. He acknowledged that some of us might know quite a lot about it, and others of us might never have heard of it, but either way that alone didn’t matter.