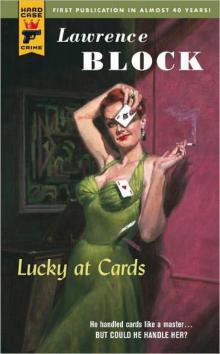

Lucky at Cards

Lawrence Block

Lucky at Cards

Lawrence Block

This is for JILL

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

A New Afterword by the Author

A Biography of Lawrence Block

1

If it hadn’t been for the dentist, I would have headed on out of town. The guy had a two-room office in the old medical building on the main drag, and I saw him Monday and Wednesday and Friday of the first week I spent in town. It took him that long to cap a pair of incisors. It hurt like hell, but by the time he was through I was no longer afraid to smile in public.

“You look human again,” he said.

I arose from the chair and smiled at myself in the mirror above the sink. The teeth were as good as new. I turned and grinned at him.

“Now the girls won’t run away,” Sy Daniels said.

“You did a good job. They look great.”

In his reception room I stood smoking a cigarette while he used a pencil and paper to figure out how much I owed him.

Sy Daniels was somewhere between forty-five and fifty, with rounded features and bushy eyebrows and thick glasses. The most memorable thing about him was the taste of his fingers. He smoked more than most dentists I’d ever had anything to do with, and he smoked some special Turkish blend that tasted even worse than it smelled, and by the time I had gone to him three times I dreaded the taste of his fingers as much as the filling and capping.

I was nearly finished with my cigarette when he turned around to look up at me and tell me I owed him sixty bucks. The fee seemed reasonable but hurt anyway. I dug out my wallet and counted out the bread in tens. I gave him the bills and he marked the tab paid and handed it to me. I stuffed it in a pocket and managed a smile.

“Between you and a few poker games,” I said, “this wallet is getting pretty flat.”

“You play poker?”

“A little,” I said. “I used to lose a few bucks a week in Chicago. We had a regular game there. But I haven’t been playing since I hit your fair city.”

“There are plenty of games.”

“If you like to play with strangers. I don’t.”

The dentist shook out a cigarette and offered the pack to me. I said thanks but no thanks and he lit his and smelled up the office some more. “I know what you mean,” Sy said. “About playing with strangers. But if you like a friendly game, we’ve got a small group of fellows who meet every Friday night. There’s a seat open tonight, if you’re interested.”

I let my eyes light up. Then I lowered them and chewed on my upper lip for a few beats. “I’d love to play,” I said. “But—”

“But what?”

“Well, I wouldn’t want to get in over my head. What kind of stakes do you fellows play for?”

He told me it was just a friendly game, dollar limit, dealer’s choice. They played five-card stud and seven-card stud and straight draw. They had a three-raise limit, no sandbagging, no high-low, no wild cards. My eyes lit up all over again. I told him that sounded just about perfect, that I’d been afraid for a minute that the game was one of those wild table-stakes ones where you needed a few hundred dollars to sit down.

“Oh, nothing like that,” Sy Daniels told me. “This is just a friendly game, Bill. I think you’ll like it.”

We made the arrangements. The game was at the house of somebody named Murray Rogers, a tax lawyer. Daniels was going home for dinner. He invited me to try his wife’s cooking but I dodged that with a story about a dinner appointment. He mentioned a drugstore uptown and said that if I could be there around a quarter to eight he’d pick me up and run me over to the game. That was fine, I said. I shook hands with him and left.

It was time for lunch. I had a pair of hamburgers at a lunch counter on Main Street and tried out my new teeth on the ground maybe-chuck. It was nice being able to bite into food again. I drank a few cups of coffee, smoked a cigarette, left the joint and took a bus back to my hotel. I was staying downtown at the Panmore and I walked through the lobby to the elevator without taking a peek at the desk. I’d been in town a week and they were about due to ask me for part of my tab, which could be embarrassing. I wasn’t too flush.

In my room I found out just how flush I was. I dumped my wallet on the bed, then found the rest of my poke in the dresser between a pair of white shirts. I counted it all up and it came to a shade over eighty dollars. I owed about double that to the Panmore; I’d been eating two or three meals a day there to make my cash last as long as I could.

I put all the money in my wallet and stuck it in a pocket. I opened the top drawer of the dresser, took out a deck of cards, sat down on the bed and started to fool around with them. I ran through a couple of false shuffles, dealt a few rounds of seconds, ran cards off the bottom, practiced top-card peeks and false cuts.

My left thumb was a little rusty. The boys in Chicago hadn’t broken it, but they had managed to dislocate it and it took a little while to get the dexterity back. I practiced for an hour in my room and the thumb started doing what it was supposed to do.

At the end of the hour I took down the mirror from the dresser and propped it up in back of the writing desk. I sat at the desk in a straight-backed wooden chair and dealt a few rounds of seconds and bottoms while I watched myself in the mirror. When I got to the point where I couldn’t even catch myself, I knew the boys at Murray Rogers’ house weren’t going to tip to me. It would be a profitable evening all around.

I put the mirror on the dresser, stuck the deck of cards in a drawer. I went downstairs to the bar and told the bartender to pour some Cutty Sark over some ice cubes. I sat sipping the drink and thought about Chicago and a dislocated thumb and two chipped teeth.

Chicago had been a big mistake all across the board. There are a few ways for a good card mechanic to make a living, and if that’s how you make your living you have to know what those ways are. The friendly game is the easiest way—you play with solidly respectable people like Seymour Daniels and his poker buddies and you can let the deck stand up and salute without anybody tipping to the bit. The average player never looks for the gaff and never sees it when it’s used on him. You don’t even need to be talented—not a player in thirty can recognize a deck of marked cards if you give them to him and tell him to play solitaire with them. You can use readers all night long and nobody sees the light.

I just leveled with one approach. That’s how you do it when you’re on your own hook, freelancing on the poker circuit. Another is worked with a group called a card mob. There’s one mechanic, a helper who crimp-cuts for him, and a few shills who do what they’re supposed to do. Some amateur hookers do the steering for you, bringing the marks to the poker table as a prelude to some genital gymnastics. The marks drop their money and go home and the card mob splits the take.

In Chicago, I had tried the third way. I went into a real game against real gamblers, a table-stakes bit for heavy money. A mistake, of course, but I wanted to pick up a very fast couple of thou because there was a broad I was trying to impress and she impressed easily when you had the dough. She was a bottle-blonde with bedroom eyes and a Hollywood body. It’s easy to lose your sense of balance over something like that. I lost mine. I did everything wrong.

The game had been a steady thing in the back room of an all-night drugstore. You paid five dollars an hour for your chair, and for that you had sandwiches and coffee and immunity from cops and holdup men, the latter two vocations about the same thing in

Chicago. I plunged into the game cold without managing to set up a friendship with any of the players, which was a mistake right there. I sat down at ten-thirty, and by two in the morning I was twenty-three hundred dollars to the good.

Look, there’s nothing easier. A fast game has a minimum of thirty hands to an hour and the game I’d been in was faster than that. The average pot held sixty or seventy bucks. The big ones held a few hundred. You don’t have to win every hand to take a game for a bundle. You just have to win a little more than your share. I made sure I won enough, and I made sure I didn’t always win on my deal. I palmed cards, holding out an ace or a pair until they would come in handy. I picked up the cards before my deal to leave a couple of kings sitting sixth and twelfth from the top and I made sure the shuffle didn’t change the arrangement. Then a crimped card let the man to my right cut the cards right back to where I wanted them and I had kings wired to play with.

Things like that.

The hell. At two in the morning a little man with hollow eyes had seen me dealing seconds. “A goddamn number two man,” he yelled. “A stinking mechanic!”

They hadn’t even asked for an explanation. They took back their twenty-three hundred plus the five hundred I started with. They hauled me out behind the store and propped me up against the wall. One of them put on a pair of black leather gloves. He worked me over, putting most of his punches into my gut. The one that broke my teeth was a mistake—I slipped and fell into it, and the guy belted me in the mouth by accident. The thumb was supposed to break but only dislocated. They dragged me out to the street and gave a shove and I wound up in the gutter.

“Card mechanics die young around here,” the hollow-eyed little man had said. “Maybe you shouldn’t stay in Chicago too long.”

And I hadn’t stayed long at all. I returned to my hotel and picked up the couple of hundred bucks I’d left there in reserve. I washed up and knocked myself out with cheap liquor. The next afternoon I woke up with a hangover, dressed, packed a suitcase, skipped my bill and got the hell out of Chicago. I didn’t even take time to say goodbye to my bottle-blonde—I just hopped on the first train out and left it when it hit this burg.

And for a week I didn’t do anything but sleep late and drink too much and have my teeth fixed. I had the same dream every night, and each time I woke up sweating just as the men in my dream caught me cheating and stuck a gun in my face and squeezed the trigger. Each night I woke up and touched myself to make sure I was alive.

During the first few days I tried dealing now and then, trying to figure out what had gone wrong for me. The thumb didn’t work at all. I hold a deck of cards in my left hand when I deal, and the left thumb is important. It has to lift the top card for peeks, and the thumb has to have just the right touch in slipping the top card out and drawing it back for second dealing. My left thumb couldn’t do a thing. I gave up and got my teeth fixed and drank and dreamed bad dreams and waited it out.

The thumb was fine now. I was good enough so that Daniels and his friends wouldn’t spot the cheating even if they were looking for it, and they wouldn’t be looking for it. I finished my drink and ordered another, trying to figure out just how much the game would be worth to me. The average pot in the buck-limit game will hold eight or nine dollars, of which the winner puts in about two-fifty or three. That’s in a five-card game; in seven-card stud the average pot runs closer to twelve, with four or five of the total coming from the winner. So you can figure the winner’s profit on a hand at around six or seven dollars. If you pick up three pots more than average per hour, you’ll take around a hundred dollars out of a five-hour game.

Even without giving myself the best of it, I figured to be a winner in Daniels’ game. I had played the game more and I knew more about it than the rest of them. But I couldn’t afford to win on talent alone.

Well, change that. On talent, yes. On legit talent, no. With a little cheating the game figured to be worth two or three hundred dollars, and I figured I could win that much without their becoming suspicious.

I signed a check for my drinks and put a buck on the bar for the bartender. I caught a movie, then grabbed a meal. After dinner I took a hack to the drugstore and waited for Dentist Daniels to come to me.

Like a lamb to slaughter.

2

The big gray Olds the dentist drove was so new he hadn’t got around to stripping the plastic film off the rear seats. The game was about half a mile from the drugstore he picked me up at and he chattered for the full distance, giving me a quick briefing on the game and the players. I didn’t figure to need it but I let the information soak in for future reference.

There were two doctors, an insurance man, a CPA, Murray Rogers and Sy Daniels and me. Rogers and the accountant—a guy named Ed Hart—were the strong players, according to Daniels. The insurance man played a good game but gave his hands away, tightening up when he held good stuff and relaxing on a bluff. One of the doctors—either the internist or the eye man, it was hard to keep them straight—played too many hands and chased straights and flushes all night long.

I asked Daniels about his own game.

“About average,” he said. “I win sometimes and I lose other times. Anything else you want to know?”

“Nothing I can think of.” I laughed. “It doesn’t make a hell of a lot of difference, Sy. I’ll forget everything you told me the minute I sit down at the table. That’s my trouble—I get too much kick out of the game to concentrate on it.”

“Well, it’s no fun if you have to work too hard at it.”

“That’s it,” I said. “When my luck runs good I win money. When it turns sour I lose. It’s more a question of luck than anything else.” And luck has about as much to do with poker as skill has with a crap game.

Daniels took a left turn, letting the power steering do all the work. He offered me a cigarette and I shook my head and lighted one of my own. Then he pulled the Olds over to the curb, leaned on the power brakes, parked the car. We walked a few doors down the street to an all-brick ranch set on a big lot. The grass had a fresh crew cut and the hedges were planted in toy evergreens. The doorbell played My Dog Has Fleas when Daniels gave it a jab. The tune was laboring through the second chorus when Murray Rogers opened the door.

“You boys are late,” he rumbled. “Let’s get rolling, team.”

He was a big man with a heavy head and a thick neck. His hair was iron gray and he had a full mustache the same color. He was wearing gray flannel slacks and a plaid shirt open at the throat, a short-sleeved thing that let you see how muscular his arms were. He didn’t look like a tax lawyer. He looked more like somebody who owned a hunting lodge, something like that.

We followed him through a built-in chrome-plated kitchen and down a flight of stairs to what they call the family room in the real estate ads. The vinyl tile on the floor was patterned to resemble parquet. The paneling was knotty cedar and the ceiling beams were exposed in mock-Colonial. Seven folding chairs crouched around an octagonal poker table, one of those functional models with wells for chips and circular spaces for drinks. Four of the chairs were occupied. The men in them stood up, Sy introduced me, and we shook hands all around.

“Sy was telling me about your accident,” Murray Rogers said. “It sounded like one hell of a shakeup.”

“It wasn’t a picnic.”

“Sounds as though you were lucky to get out of it alive.”

“I was,” I said. “I blew a front tire at seventy and shot off the road. I thought the car was going to flip, but it didn’t. I chopped a pair of teeth on the steering wheel and caught a few body bruises. That was all.”

“Lucky,” the insurance man said. That was Ken Jameson.

Murray asked me what I was drinking. I said scotch would do fine. I sat down and started a fresh cigarette. Evidently Sy Daniels had filled everyone in on my cover story. I had been a plastic firm’s salesman in Chicago, my job had disappeared when the company had merged with a larger outfit, and I had been heading f

or New York to look for work when the car had done the shimmy-shake and had wound up off the road. It was an adequate front, explaining simultaneously why I didn’t have a car, why I wasn’t working, and why my teeth needed a repair job.

I took the drink from Murray and sipped good scotch. Ed Hart and Harold Barnes broke open two fresh decks of Bee cards and shuffled them up. Barnes was the internist, a gangling fellow with a weak chin and thick glasses. He shuffled a final time, then ran the cards around the table until Sy caught the first jack for the deal. I bought thirty dollars worth of chips from Murray Rogers. Sy tossed his half-buck ante into the middle and we started to play. He dealt draw poker, jacks or better, and Lou Holman opened under the gun. Holman was the oculist. I caught a bust and folded before the draw. Barnes stuck around to buy one card to an open straight and picked up the pot.

I took things slow for the first half hour, laying back and getting a line on the game. It wasn’t quite as friendly as Sy had made it sound. Poker never is. The object of the game is winning money, and you can only win if somebody else loses. They played a sociable sort of game but nobody was giving anything away.

I picked off a pair of baby pots in the first few rounds. Then with about twenty minutes gone I folded early in a hand of seven-card stud and held back an ace before I pitched my hand into the discard. Two hands later I caught an ace for my hole card, covering the motion by reaching for a cigarette with my free hand. I was sitting with the empty chair on my left and that made the catch a little simpler.

I bet half a buck on the ace and got three callers. On the second round I picked up a jack and Lou Holman paired his queen. He bet a buck on the queens and Ed Hart bumped a buck with a king and a five showing. I called. Barnes folded.

Everyone got garbage on the third round. Holman checked, Hart bet a buck and I raised him. Holman made a bad call—either Hart or I had to be telling the truth, and he was chasing aces or kings or both with his pair of queens. He folded on the last round and my wired aces picked up the pot when Hart called my last bet. He had kings with no help for them. I pulled in the pot.