There's a (Slight) Chance I Might Be Going to Hell - v4

Laurie Notaro

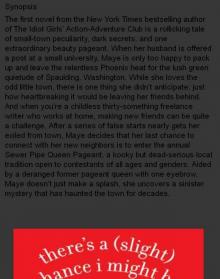

Synopsis

The first novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Idiot Girls’ Action-Adventure Club is a rollicking tale of small-town peculiarity, dark secrets, and one extraordinary beauty pageant. When her husband is offered a post at a small university, Maye is only too happy to pack up and leave the relentless Phoenix heat for the lush green quietude of Spaulding, Washington. While she loves the odd little town, there is one thing she didn’t anticipate: just how heartbreaking it would be leaving her friends behind. And when you're a childless thirty-something freelance writer who works at home, making new friends can be quite a challenge. After a series of false starts nearly gets her exiled from town, Maye decides that her last chance to connect with her new neighbors is to enter the annual Sewer Pipe Queen Pageant, a kooky but dead-serious local tradition open to contestants of all ages and genders. Aided by a deranged former pageant queen with one eyebrow, Maye doesn’t just make a splash, she uncovers a sinister mystery that has haunted the town for decades.

There’s A (Slight) Chance I Might Be Going To Hell

Laurie Notaro

Copyright © 2007 by Laurie Notaro

To Corbett, who gave me my Burgess Meredith

Prologue

SPRING, 1956

The moment the girl stepped onto the stage, the circle of a spotlight swung toward her, announcing her presence above the audience in a sheer, clean illumination. The crowd before her suddenly quieted, as if expecting something truly spectacular to occur. It would have to be spectacular; after all, Mary Lou Winton, the contestant before her, had let loose a greased baby pig onstage, which she managed to lasso, hog-tie, and brand—with a branding iron fashioned to look like a sewer pipe, no less—in a definitive nine seconds flat. It was, in fact, confirmed by the audience, who counted down as Mary Lou whipped that rope and then stomped over to plunge the glowing iron. And it was further rumored that Ruth Watson was planning to bring her rifle out onto the stage and shoot every winged fowl right out of the sky, all in her evening gown attire, for her talent segment.

Farm antics, the girl scoffed to herself, wondering if such a thing really could be considered as a talent or just an episode of unfortunate breeding. She knew she could not let any of that concern her as she looked out over the crowd, searching the faces. She knew almost everyone—everyone who was waiting to hear her sing.

She smiled softly, an expression that seemed gentle.

If only I had ruby slippers, she thought to herself. The light that would have caught them would have been astounding, the sparkle would have bounced off of them like rockets, far more impressive than an oily piglet or dead birds. She looked down at her feet, at her pair of last year’s Sunday shoes—now buffed a bright cherry red by her father, who had been so proud when he surprised her with them—and saw that they did not sparkle, but produced a dull, minuscule shine.

Behind her, she heard Mrs. A. Melrose from the church choir begin playing the piano; this was her cue, and the pianist had better keep time. Although she considered herself a devoted Christian woman overflowing with generosity, Mrs. Melrose thought little of donating her time to the endeavor and suggested that instead she exchange her musical services for the girl’s scrubbing a week’s worth of the accompanist’s and her flatulent husband’s laundry. Despite the gruesome task that lay ahead in the Melroses’ wash bin the next day, the girl continued to smile as she drew a deep, full breath, so full that the replica blue gingham pinafore fashioned from a picnic tablecloth seemed to expand slightly, making the ketchup stains that stubbornly remained on the cloth look like she had encountered Ruth Watson’s rifle. She waited: one, two, three.

The next note was hers. She was ready.

“Somewheeeeere over the rainbow…”

Her voice glided sweetly over the stage into the audience and twirled in the air above them like magic. She could see it on the faces of the people watching her, listening to her, heads tilted slightly to the side, as they smiled back at her. This was no pig-roping event, and no explosion of feathers was going to trickle down from the clouds.

This was talent.

I have it, she thought giddily to herself as she finished the first verse, as her voice continued on clear, strong, and with the right touch of delicacy. It is mine.

She saw him, standing in the back, far beyond the crowd assembled in the square—the most handsome man she had ever seen in real life, the one who could save her. With a bouquet spilling with flowers in the crook of his arm, he leaned up against his brand-new powder-blue Packard Caribbean convertible with its whitewall tires and gleaming, curvaceous chrome bumpers. It was a glorious machine. It suited him. Cars like that were rare in this town, and so were the men they suited. She saw him smiling at her, and to her he delivered a nod of encouragement.

She felt herself blush a shade. The surge of delight was just the push she needed to soar into the last verse and deliver with earnest, heartfelt yearning, “Why, oh, why can’t I?”

The moment the last note evaporated into the air, the crowd burst forth with a shower of applause, the hands of the audience clapping heartily, and as she looked toward the back of the crowd, she saw that he was clapping, too, his arms full of tulips, roses, and lilies. Clapping for her.

Excitement raced up her spine like a block shooting up to hit the bell on a Hi Striker carnival game.

It was hers, she had done it, she knew it, she owned it. She could actually feel the weight of the crown being placed on her head, she could foresee the way that it would sparkle. She wanted it to sparkle brightly, feverishly, ferociously. Sparkle so bright it would blind them. Show this town that she was the queen of this scrap heap, this tiny little town with nothing in it but sewer pipes and waste. From this moment, it was all hers, all of it. If she wanted ruby slippers, she would get ruby slippers, not last year’s fake, cheap Sunday shoes painted red with a dirty rag. She was more than that.

It was hers, the crown, the town—she had won and she would take it. She knew it like she had never known anything else. As if there was any other choice! The pig tosser, the bird slayer? This was now her town, her kingdom.

To reign as she saw fit.

She smiled sweetly again, then closed her eyes slowly, laid her arm over her chest, holding her hand to her heart the way she had seen it done in the movies, and crossed one leg deeply behind the other in what could only be described as a true queenly and magnificent gesture.

And with that, she took a bow.

1

The Queen Leaves the Hive

Every morning on her daily trip to the Dumpster behind Starbucks, Maye made sure she was wearing lipstick and carrying her lucky stick. Perched on an overturned milk crate, she used the former broom handle to poke at the trash with one hand while batting away the flies with the other.

It was searing hot. Within minutes, Maye could feel the relentless Phoenix sun bearing down on the crown of her head and the flush of sweat trickling down her temples and detouring into her eyes, making them burn with salt. She poked on with her lucky stick, overturning a piece of cardboard to reveal an almost uneaten enchilada dinner from Starbucks’ neighbor, Don Juan’s Taco Village, resting perfectly atop an empty Solo cup box.

“Bingo,” she sang, smiling like the Cheshire cat as she reached over to snatch the Styrofoam plate from its spot. “Come to Mama.” She rose up on tippy-toe as her outstretched arm grazed the blazing metal side of the Dumpster, causing her to flinch slightly.

“I am going to get you,” she hissed, determined to reach the objective—from her vantage point, it looked to be a cheese enchilada and a beef taco with rice and bean

s—as she stretched as far as she could, her fingers now brushing the pearly white dish. With only one foot now balancing on the milk crate, Maye leaned as deeply into the Dumpster as she could and, with one determined push, grabbed the dinner, the cheese on the refried beans still soft in the bubbling summer heat, and pulled herself out of the metal bin without spilling so much as a drop of the red, runny enchilada sauce.

Maye heard the creak of metal hinges as a door opened behind her.

“Hey!” a loud voice shouted.

With the entrée in her hands, she turned around to face a young man wearing a green barista’s apron.

“You don’t need to dig around in there,” the young man said. “I’ve got something for you here.”

“I was wondering where you were,” Maye replied. “I was here on time!”

She turned on the milk crate and with a little hop, lobbed the dinner square back into the Dumpster, and with her lucky stick in hand, turned her attention to the perfect, four-sided, undented, untorn, and unstained-with-enchilada-sauce Solo box that was exactly the size she needed to hold her food processor. She beamed as she lifted it from the bin.

“Thanks, Carlos, I’ll take whatever you’ve got,” Maye replied as she gazed admiringly at her find. “But this one is perfect. A beauty like this would be seven bucks at U-Haul. But I wish those Don Juan kids would get their recycling and trash bins straight. You don’t know how many beautiful boxes have been tragically disfigured and rendered useless by a sinister dollop of nacho-cheese sauce. There should be legislation, I tell you.”

“So how many days now?” Carlos asked, shielding his eyes from the sun with his hand.

“Four. Four. I’m moving across the country in four days,” she replied. “I can’t believe it. I’m flipping out. I have so much left to do it’s amazing.”

“Well, I hope these help, Maye,” he said, lifting up a tied bundle of flattened Starbucks cartons.

“Everything helps,” Maye said, balancing the lucky stick against the side of the Dumpster. “I would have spent a fortune on cardboard if it wasn’t for you and my favorite recycling bin. Thank you. And thanks for not calling strip-mall security on me for the last month.”

“Well, these days there’s typically more eBayers digging through the boxes than bums, but it never hurts to distinguish yourself with a nice shower and leaving your invisible friend at home.”

“And the lipstick,” Maye added. “Apparently, sometimes a shower isn’t enough for the Dunkin’ Donuts people. I learned that one the hard way.”

“See you tomorrow?” Carlos said as he opened the back door, the metal hinges groaning.

“Eight o’clock sharp,” she chirped. Hugging her perfect box, she stepped off the milk crate and right into a small puddle of hobo throw-up.

“I can’t, I just can’t, Charlie,” Maye said as she navigated through the stacks of boxes Carlos had given her, most of which were now half filled with things that once lined the bookshelves in the living room. “I know I said I would go, but I still have so much to pack.”

“I’ll pack double time,” Charlie offered from behind a tower of Starbucks logos. “I can get it done. You have to go, you promised. This will be the last time you see Kate for a while. You need to go.”

Maye looked around the living room. She knew she should go to dinner with her friend Kate as she had promised she would, but it just seemed impossible. She didn’t know who her husband thought he was kidding. The movers would arrive in four days, and everywhere Maye looked, there was more to do and it was multiplying by the hour. Their house had become a puzzle of open boxes, packing paper, tape guns, and piles of their belongings. Every time she emptied a bookshelf into a box, more books would appear on it when she turned around. She bought gigantic rolls of bubble wrap more often than she bought food. And there was so much she hadn’t even begun to tackle yet. It seemed like she still had three hundred things on her to-do list, including turning the utilities off; doing an Internet search to find out which motels would accommodate Mickey, their three-year-old Australian shepherd, for their drive up to Spaulding, Washington, their soon-to-be home; emptying out the junk drawer; and hoping that if there was a shooting in the neighborhood it wouldn’t make the nightly news and cause the lady who bought the house to back out of the sales contract. She had to decide which clothes she might one day fit into again and which were now definitely out of reach—unless a famine and plague hit simultaneously—and thus headed for a Salvation Army donation box. If only Charlie had pushed harder for the moving arrangements when he was negotiating the terms of his new position as an English professor, Maye thought to herself, I wouldn’t have to worry so much, but it was his first job and the university was a small one in an even smaller town. As her husband reminded her, he was lucky to even get hired straight out of graduate school by such a prestigious university. Having his new employer arrange and then pay for moving was a little out of the question.

“I know I should go to dinner, but I just don’t see how,” Maye declared as she picked up one of Carlos’s flattened boxes and assembled it. “The dishes still need to be packed. I have to clean out the refrigerator and make it look like humans used it for something other than a scientific testing center for food expiration dates. And I curse the day you learned to read, Charlie. Why do we have so many books? We have so many books. There’s nothing wrong with illiterate people. I don’t know why I stopped dating them.”

“Go to dinner. I promise I’ll pick up the slack,” Charlie said, as he took the box from her hands and ripped a tape gun across the bottom of it.

“I had a dream last night that the movers came and the only thing that was packed were all of my shirts,” she said. “And I had to pack the last thousand of your books in front of them, topless, while you went out and bought them donuts, after which the movers tried to toss them onto me like I was the ring toss at the carnival.”

“Go to dinner,” her husband repeated. “I promise I’ll finish the next fifteen things on your list if you go. That dream proves you need to relax a little and have some downtime. If you don’t go, I’m afraid you’ll start sleepwalking and I’ll wake up tomorrow wrapped in a giant tape cocoon, wiggling like larvae.”

“I just don’t know. I don’t think I can afford the time,” Maye replied.

“You can’t afford not to go,” he insisted. “Kate is one of your best friends. When do you think you’re going to see her again? We’re moving fifteen hundred miles away, you know. It’s not going to be a walk around the corner anymore.”

After thinking for a moment, Maye nodded. “You’re right,” she relented. “I promised I would. I should go. You promise you’ll do fifteen things on the list?”

“I promise,” Charlie said as he held his hand up. “I swear on the tape gun.”

“That doesn’t mean you can pack fifteen pairs of socks and call it a night, you know,” she told him as she shook her finger. “Because if you pack a box of toothpicks and tell me you’ve done a hundred and fifty things, Charlie, I’ll warn you right now: when the movers show up, they’ll be tossing donuts at your shirtless boobs.”

Within the hour before she was due at Kate’s, Maye had finished packing her vase, cleaned out the two top shelves of the fridge, and packed all the books in the bookcase (again). She tore through what remained in her closet and pulled out a light vintage checked cotton shirtdress, perfect for drinking wine on the back patio of her friend’s apartment on a hot summer night. In other words, a good sweating dress. For six long months in Phoenix, even after the sun slides behind the mountains, it’s a wise move to go straight to wash-and-wear. Anything synthetic will not only cling to your wet, leaking skin like a hickey on the neck of a high school senior on picture day but will cost you more than a reckless cocaine habit in dry cleaning. Maye looked down and realized her stubbly legs could use a little updating, but she was running late and it was far too hot for tights. Well, she figured, it was only she and Kate, anyway, and all they were rea

lly going to be doing was losing body fluids and getting tipsy. Unless a hungry cat showed up, no one was going to be touching her prickly legs.

“Charlie,” she called grabbing her purse and house keys. “I’m leaving. I’ll see you tonight.”

“Okay,” he shouted from the back of the house. “Have fun!”

Maye started down the three blocks to Kate’s apartment. In her own yard, she noticed how the verbena had finally come into its own, reaching and sprawling on the side of the house where she had planted it in the spring. She hoped her neighbor wouldn’t mind when it reached the chain-link fence that separated their yards and was the reason Maye had planted the verbena in the first place. By next spring, the plant should have a firm hold on the fence, weaving in and out of the wire diamonds in ribbons of tiny purple flowers.

It was then that Maye realized that she wouldn’t be there to see it. In four days, her house, the cute brick 1927 downtown bungalow that she and Charlie had scrimped and saved and struggled to buy when they were barely married, would belong to someone else. The wood floors they had refinished by themselves, the soapstone kitchen counter she had uncovered as she demolished a layer of eroding, mottled tile with a hammer and a flat-head screwdriver one night at 1 A.M. when Charlie was late coming home and she was furious. Those bookcases, and the fireplace they flanked, she had stripped seven layers of lead paint off of, only to discover that the mantel had been devoured by termites decades earlier. It was so far gone she had actually poked her fingers through the wood and decided to rebuild it herself. The jacaranda trees they had planted in the backyard, where a dust storm had threatened to suck them down as she and Charlie struggled, bandannas tied over their mouths, to keep them from toppling over. It was one thing to sell a house, Maye suddenly thought; it was another to understand it wasn’t yours any longer.