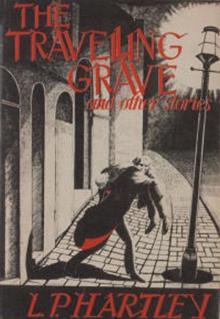

The Travelling Grave and Other Stories

L. P. Hartley

The Travelling Grave

and Other Stories

By

L. P. Hartley

ARKHAM HOUSE: Publishers Saulk City,Wisconsin

1948

Table of Contents

A VISITOR FROM DOWN UNDER

PODOLO

THREE, OR FOUR, FOR DINNER

THE TRAVELLING GRAVE

FEET FOREMOST

THE COTILLON

A CHANGE OF OWNERSHIP

THE THOUGHT

CONRAD AND THE DRAGON

THE ISLAND

NIGHT FEARS

THE KILLING BOTTLE

A VISITOR FROM DOWN UNDER

‘And who will you send to fetch him away?’

AFTER a promising start, the March day had ended in a wet evening. It was hard to tell whether rain or fog predominated. The loquacious bus conductor said, ‘A foggy evening,’ to those who rode inside, and ‘A wet evening,’ to such as were obliged to ride outside. But in or on the buses, cheerfulness held the field, for their patrons, inured to discomfort, made light of climatic inclemency. All the same, the weather was worth remarking on: the most scrupulous conversationalist could refer to it without feeling self convicted of banality. How much more the conductor who, in common with most of his kind, had a considerable conversational gift.

The bus was making its last journey through the heart of London before turning in for the night. Inside it was only half full. Outside, as the conductor was aware by virtue of his sixth sense, there still remained a passenger too hardy or too lazy to seek shelter. And now, as the bus rattled rapidly down the Strand, the footsteps of this person could be heard shuffling and creaking upon the metal-shod steps.

‘Anyone on top?’ asked the conductor, addressing an errant umbrella-point and the hem of a mackintosh.

‘I didn’t notice anyone,’ the man replied.

‘It’s not that I don’t trust you,’ remarked the conductor pleasantly, giving a hand to his alighting fare, ‘but I think I’ll go up and make sure.’

Moments like these, moments of mistrust in the infallibility of his observation, occasionally visited the conductor. They came at the end of a tiring day, and if he could he withstood them. They were signs of weakness, he thought; and to give way to them matter for self-reproach.

‘Going barmy, that’s what you are,’ he told himself, and he casually took a fare inside to prevent his mind dwelling on the unvisited outside. But his unreasoning disquietude survived this distraction, and murmuring against himself he started to climb the steps.

To his surprise, almost stupefaction, he found that his misgivings were justified. Breasting the ascent, he saw a passenger sitting on the right-hand front seat; and the passenger, in spite of his hat turned down, his collar turned up, and the creased white muffler that showed between the two, must have heard him coming; for though the man was looking straight ahead, in his outstretched left hand, wedged between the first and second fingers, he held a coin.

‘Jolly evening, don’t you think?’ asked the conductor, who wanted to say something. The passenger made no reply, but the penny, for such it was, slipped the fraction of an inch lower in the groove between the pale freckled fingers.

‘I said it was a damn wet night,’ the conductor persisted irritably, annoyed by the man’s reserve.

Still no reply.

‘Where you for?’ asked the conductor, in a tone suggesting that wherever it was, it must be a discreditable destination.

‘Carrick Street.’

‘Where?’ the conductor demanded. He had heard all right, but a slight peculiarity in the passenger’s pronunciation made it appear reasonable to him, and possibly humiliating to the passenger, that he should not have heard.

‘Carrick Street.’

‘Then why don’t you say Carrick Street?’ the conductor grumbled as he punched the ticket.

There was a moment’s pause, then:

‘Carrick Street,’ the passenger repeated.

‘Yes, I know, I know, you needn’t go on telling me,’ fumed the conductor, fumbling with the passenger’s penny. He couldn’t get hold of it from above; it had slipped too far, so he passed his hand underneath the other’s and drew the coin from between his fingers.

It was cold, even where it had been held. ‘Know?’ said the stranger suddenly. ‘What do you know?’ The conductor was trying to draw his fare’s attention to the ticket, but could not make him look round.

‘I suppose I know you are a clever chap,’ he remarked. ‘Look here, now. Where do you want this ticket? In your button-hole?’

‘Put it here,’ said the passenger.

‘Where?’ asked the conductor. ‘You aren’t a blooming letter-rack.’

‘Where the penny was,’ replied the passenger. ‘Between my fingers.’

The conductor felt reluctant, he did not know why, to oblige the passenger in this. The rigidity of the hand disconcerted him: it was stiff, he supposed, or perhaps paralysed. And since he had been standing on the top his own hands were none too warm. The ticket doubled up and grew limp under his repeated efforts to push it in. He bent lower, for he was a good-hearted fellow, and using both hands, one above and one below, he slid the ticket into its bony slot.

‘Right you are, Kaiser Bill.’

Perhaps the passenger resented this jocular allusion to his physical infirmity; perhaps he merely wanted to be quiet. All he said was:

‘Don’t speak to me again.’

‘Speak to you!’ shouted the conductor, losing all self-control. ‘Catch me speaking to a stuffed dummy!’ Muttering to himself he withdrew into the bowels of the bus.

At the comer of Carrick Street quite a number of people got on board. All wanted to be first, but pride of place was shared by three women who all tried to enter simultaneously. The conductor’s voice made itself audible over the din: ‘Now then, now then, look where you’re shoving! This isn’t a bargain sale. Gently, please, lady; he’s only a pore old man.’ In a moment or two the confusion abated, and the conductor, his hand on the cord of the bell, bethought himself of the passenger on top whose destination Carrick Street was. He had forgotten to get down. Yielding to his good nature, for the conductor was averse from further conversation with his uncommunicative fare, he mounted the steps, put his head over the top and shouted ‘Carrick Street! Carrick Street!’ That was the utmost he could bring himself to do. But his admonition was without effect; his summons remained unanswered; nobody came.

‘Well, if he wants to stay up there he can,’ muttered the conductor, still aggrieved. ‘I won’t fetch him down, cripple or no cripple.’ The bus moved on. He slipped by me, thought the conductor, while all that Cup-tie crowd was getting in.

The same evening, some five hours earlier, a taxi turned into Carrick Street and pulled up at the door of a small hotel. The street was empty. It looked like a cul-de-sac, but in reality it was pierced at the far end by an alley, like a thin sleeve, which wound its way into Soho.

‘That the last, sir?’ inquired the driver, after several transits between the cab and the hotel.

‘How many does that make?’

‘Nine packages in all, sir.’

‘Could you get all your worldly goods into nine packages, driver?’

‘That I could; into two.’

‘Well, have a look inside and see if I have left anything.’ The cabman felt about among the cushions. ‘Can’t find nothing, sir.’

‘What do you do with anything you find?’ asked the stranger.

‘Take it to New Scotland Yard, sir,’ the driver promptly answered.

‘Scotland Yard?’ said the stranger. ‘Strike a match, will you, and let me have a look.�

� But he, too, found nothing, and reassured, followed his luggage into the hotel.

A chorus of welcome and congratulation greeted him. The manager, the manager’s wife, the Ministers without portfolio of whom all hotels are full, the porters, the lift-man, all clustered around him.

‘Well, Mr. Rumbold, after all these years! We thought you’d forgotten us! And wasn’t it odd, the very night your telegram came from Australia we’d been talking about you! And my husband said, “Don’t you worry about Mr. Rumbold. He’ll fall on his feet all right. Some fine day he’ll walk in here a rich man.” Not that you weren’t always well off, but my husband meant a millionaire.’

‘He was quite right,’ said Mr. Rumbold slowly, savouring his words. I am.

‘There, what did I tell you?’ the manager exclaimed, as though one recital of his prophecy was not enough. ‘But I wonder you’re not too grand to come to Rossall’s Hotel.’

‘I’ve nowhere else to go,’ said the millionaire shortly. ‘And if I had, I wouldn’t. This place is like home to me.’

His eyes softened as they scanned the familiar surroundings. They were light grey eyes, very pale, and seeming paler from their setting in his tanned face. His cheeks were slightly sunken and very deeply lined; his blunt-cndcd nose was straight. He had a thin, straggling moustache, straw-coloured, which made his age difficult to guess. Perhaps he was nearly fifty, so wasted was the skin on his neck, but his movements, unexpectedly agile and decided, were those of a younger man.

‘I won’t go up to my room now,’ he said, in response to the manageress’s question. ‘Ask Clutsam —he’s still with you?—good—to unpack my things. He’ll find all I want for the night in the green suitcase. I’ll take my despatch-box with me. And tell them to bring me a sherry and bitters in the lounge.’

As the crow flies it was not far to the lounge. But by the way of the tortuous, ill-lit passages, doubling on themselves, yawning with dark entries, plunging into kitchen stairs —the catacombs so dear to habitues

of Rossall’s Hotel —it was a considerable distance. Anyone posted in the shadow of these alcoves, or arriving at the head of the basement staircase, could not have failed to notice the air of utter content which marked Mr. Rumbold’s leisurely progress: the droop of his shoulders, acquiescing in weariness; the hands turned inwards and swaying slightly, but quite forgotten by their owner; the chin, always prominent, now pushed forward so far that it looked relaxed and helpless, not at all defiant. The unseen witness would have envied Mr. Rumbold, perhaps even grudged him his holiday air, his untroubled acceptance of the present and the future.

A waiter whose face he did not remember brought him the aperitif, which he drank slowly, his feet propped unconventionally upon a ledge of the chimney-piece; a pardonable relaxation, for the room was empty. Judge therefore of his surprise when, out of a fire-engendered drowsiness, he heard a voice which seemed to come from the wall above his head. A cultivated voice, perhaps too cultivated, slightly husky, yet careful and precise in its enunciation. Even while his eyes searched the room to make sure that no one had come in, he could not help hearing everything the voice said. It seemed to be talking to him, and yet the rather oracular utterance implied a less restricted audience. It was the utterance of a man who was aware that, though it was a duty for him to speak, for Mr. Rumbold to listen would be both a pleasure and a profit.

1 ... A Children’s Party,’ the voice announced in an even, neutral tone, nicely balanced between approval and distaste, between enthusiasm and boredom; ‘six little girls and six little’ (a faint lift in the voice, expressive of tolerant surprise) ‘boys. The Broadcasting Company has invited them to tea, and they arc anxious that you should share some of their fun.’ (At the last word the voice became completely colourless.) ‘I must tell you that they have had tea, and enjoyed it, didn’t you, children?’ (A cry of‘Yes,’ muffled and timid, greeted this leading question.) ‘We should have liked you to hear our table-talk, but there wasn’t much of it, we were so busy eating.’ For a moment the voice identified itself with the children. ‘But we can tell you what we ate. Now, Percy, tell us what you had.’

A piping little voice recited a long list of comestibles; like the children in the treacle-well, thought Rumbold, Percy must have been, or soon would be, very ill. A few others volunteered the items of their repast. ‘So you see,’ said the voice, ‘we have not done so badly. And now we are going to have crackers, and afterwards’ (the voice hesitated and seemed to dissociate itself from the words) ‘Children’s Games.’ There was an impressive pause, broken by the muttered exhortation of a little girl. ‘Don’t cry, Philip, it won’t hurt you.’ Fugitive sparks and snaps of sound followed; more like a fire being kindled, thought Rum-bold, than crackers.

A murmur of voices pierced the fusillade.

‘What have you got, Alec, what have you got?’

‘I’ve got a cannon.’

‘Give it to me.’

‘No.’

‘Well, lend it to me.’

‘What do you want it for?’

‘I want to shoot Jimmy.’

Mr. Rumbold started. Something had disturbed him. Was it imagination, or did he hear, above the confused medley of sound, a tiny click? The voice was speaking again. ‘And now we’re going to begin the Games.’ As though to make amends for past lukewarmness a faint flush of anticipation gave colour to the decorous voice.

‘We will commence with that old favourite, Ring-a-Ring of Roses.’

The children were clearly shy, and left each other to do the singing. Their courage lasted for a line or two and then gave out. But fortified by the speaker’s baritone, powerful though subdued, they took heart, and soon were singing without assistance or direction. Their light wavering voices had a charming effect. Tears stood in Mr. Rumbold’s eyes. ‘Oranges and Lemons’ came next. A more difficult game, it yielded several unrehearsed effects before it finally got under way. One could almost see the children being marshalled into their places, as though for a figure in the Lancers. Some of them no doubt had wanted to play another game; children are contrary; and the dramatic side of ‘Oranges and Lemons,’ though it appeals to many, always affrights a few.

The disinclination of these last would account for the pauses and hesitations which irritated Mr. Rumbold, who, as a child, had always had a strong fancy for this particular game. When, to the tramping and stamping of many small feet, the droning chant began, he leaned back and closed his eyes in ecstasy. He listened intently for the final accelerando which leads up to the catastrophe. Still the prologue maundered on, as though the children were anxious to extend the period of security, the joyous carefree promenade which the great Bell of Bow, by his inconsiderate profession of ignorance, was so rudely to curtail. The Bells of Old Bailey pressed their usurer’s question; the Bells of Shoreditch answered with becoming flippancy; the Bells of Stepney posed their ironical query, when suddenly, before the great Bell of Bow had time to get his word in, Mr. Rumbold’s feelings underwent a strange revolution. Why couldn’t the game continue, all sweetness and sunshine? Why drag in the fatal issue? Let payment be deferred; let the bells go on chiming and never strike the hour. But heedless of Mr. Rumbold’s squeamishness, the game went its way.

After the eating comes the reckoning.

Here is a candle to light you to bed,

And here comes a chopper to chop oft” your head!

Chop—chop—chop.

A child screamed, and there was silence.

Mr. Rumbold felt quite upset, and great was his relief when, after a few more half-hearted rounds of ‘Oranges and Lemons,’ the Voice announced, ‘Here We Come Gathering Nuts and May.’ At least there was nothing sinister in that. Delicious sylvan scene, comprising in one splendid botanical inexactitude all the charms of winter, spring, and autumn. What superiority to circumstances was implied in the conjunction of nuts and May! What defiance of cause and effect! What a testimony to coincidence! For cause and effect is against us, as witness the fate

of Old Bailey’s debtor; but coincidence is always on our side, teaching us how to eat our cake and have it! The long arm of coincidence! Mr. Rumbold would have liked to clasp it by the hand.

Meanwhile his own hand conducted the music of the revels and his foot kept time. Their pulses quickened by enjoyment, the children put more heart into their singing; the game went with a swing; the ardour and rhythm of it invaded the little room where Mr. Rumbold sat. Like heavy fumes the waves of sound poured in, so penetrating, they ravished the sense; so sw’eet, they intoxicated it; so light, they fanned it into a flame. Mr. Rumbold was transported. His hearing, sharpened by the subjugation and quiescence of his other faculties, began to take in new sounds; the names, for instance, of the players who were ‘wanted’ to make up each side, and of the champions who were to pull them over. For the listeners-in, the issues of the struggles remained in doubt. Did Nancy Price succeed in detaching Percy Kingham from his allegiance? Probably. Did Alec Wharton prevail against Maisie Drew? It was certainly an easy win for someone: the contest lasted only a second, and a ripple of laughter greeted it. Did Violet Kingham make good against Horace Gold? This w’as a dire encounter, punctuated by deep irregular panting. Mr. Rumbold could see, in his mind’s eye, the two champions straining backwards and forwards across the white, motionless handkerchief, their faces red and puckered with exertion. Violet or Horace, one of them had to go: Violet might be bigger than Horace, but then Horace was a boy: they were evenly matched: they had their pride to maintain. The moment when the will was broken and the body went limp in surrender would be like a moment of dissolution. Yes, even this game had its stark, uncomfortable side. Violet or Horace, one of them was smarting now: crying perhaps under the humiliation of being fetched away.

The game began afresh. This time there was an eager ring in the children’s voices: two tried antagonists were going to meet: it would be a battle of giants. The chant throbbed into a war-cry.

Who will you have for your Nuts and May,