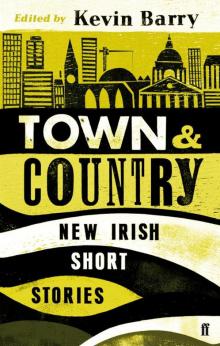

Town and Country

Kevin Barry

Also available from Faber

the faber book of best new irish short stories 2004-5

the faber book of best new irish short stories 2006-7

new irish short stories

TOWN AND COUNTRY

New Irish Short Stories

Edited and with an introduction

by Kevin Barry

This book is dedicated to the

previous editors in its series:

David Marcus and Joseph O’Connor

Contents

An Introduction KEVIN BARRY

Images DERMOT HEALY

Earworm JULIAN GOUGH

Saturday, Boring LISA MCINERNEY

Tiger MICHAEL HARDING

Godīgums KEITH RIDGWAY

The Second-Best Bar in Cadiz

ANDREW MEEHAN

The Ladder SHEILA PURDY

Barcelona MARY COSTELLO

The Mark of Death GREG BAXTER

Summer’s Wreath ÉILÍS NÍ DHUIBHNE

The Clancy Kid COLIN BARRETT

Hospitals Requests PAT MCCABE

The Recital EIMEAR RYAN

A Winter Harmonic MIKE MCCORMACK

Joyride to Jupiter NUALA NÍ CHONCHÚIR

City of Glass MOLLY MCCLOSKEY

While You Were Working NEASA MCHALE

Brimstone Butterfly DESMOND HOGAN

Paper and Ashes WILLIAM WALL

How I Beat the Devil PAUL MURRAY

About the Authors

An Introduction

Kevin Barry

I

There was a time when the short story looked – to use a great and morbidly descriptive Irish phrase – as if it might turn in to face the wall, and the expectation was of a low-key funeral with a smallish turn-out.

But now?

In every coffee trough and every garret, in the jails and in the hospitals, in university workshops and in secure units, and down the backs of pubs, and on the buses and the trains, short stories are being written; at any given moment, it seems, there are ten thousand maniacs battering their laptops with caffeinated fingers, and stories are scrawled onto the backs of beer mats, or pricked out in blood on the pale skin of the page.

Somehow, the story has come alive again and is wriggling and it has about it all the demonic energy (and the undeniable immediacy) of a newborn infant.

Every story within these covers contains that bawl of life.

II

Ireland is not so much a country as a planet. Perception operates differently here. When our writers face up to the world, I believe they work off a certain hard-to-define oddness as they set about perceiving it and recording it. Maybe there is a particular tone or note that’s sounded often – a kind of laughter in the dark. Or, more specifically, against the dark. You are going to hear that note on so many of these pages.

III

So I sent out the pleading emails and the begging letters and I made the discreet phone calls, and I waited, in modest expectation, at home in County Sligo. For a while, silence. But then, somewhere among the occult mists of autumn, the stories started to take shape and appear out there, and they came skittering along the road, and I hauled them into the house, one by one, and ran a sceptic’s eye over them.

And I was awed. Not just by the quality of the finish and the nimble delicacy of the engineering, but by the sheer variety of the methods employed – there are so many modes of attack on the short story as a form now; these writers are up to all sorts.

There are carefully crafted stories here in a classical mode but there are riffs and rants, too, and stories that employ documentary techniques, or delve into the mystics of psychogeography. There is a historical piece; there is an eerie blast from the near-future. There are stories that read like miraculously compressed novels; there are dramatic monologues; there are stories that use the pans and fades and jump-cuts of film. There is lots of funny and there is plentiful joy but the contours of our great human aches and sorrows are traced here too.

IV

What the short story at its very best can offer is an intensity difficult to match in the other prose forms. A great story can take all the air out of a room. A great story can make you loosen your collar. A great story can delineate the critical moments of a life – those moments of pregnant arrest – with a sense of shiver and glow, and for the reader those moments can linger within, and for years. They are moments with the clarity and amplitude of hallucination, and they are found in the stories of this book.

V

It is a special pleasure to present an anthology that contains many new voices. There is always a distinctive relish about the work of young and emerging writers, a jauntiness and thrust that comes directly from the very fact of being a young writer, which is a haunted and exalted state, and for that writer a time of immense excitement but also of great difficulty, when there is that vast store of Voice inside just waiting to be released but finding the moment, and the opportunity, can seem to take for ever. It’s a very cool thing to have these new voices make their clamour on the pages here.

VI

It was with a sense of cackling glee, then, that I sent this book to its publisher. These are Irish short stories, and often they come in the shapes that we know and have loved in the form but also they come at a very interesting moment, I believe, when the story is being considered anew and is being pulled in many strange and unexpected new directions. The Irish story is changing and is pulsing with great, mad and rude new energies.

Watch it now as it spirals and spins out—

Images

Dermot Healy

After Jack retired as a lecturer from the IT college we often saw him with camera in hand honing in on the black windows of deserted cottages above the beach. If the doors were open he’d step inside and haunt the ruin. I could not tell what he was after – the architecture, the stonework, the past – or maybe all of them.

He’s a strange bird, said Mrs Jay.

He is.

I could understand what he was looking at when the dead whale was washed in. Jack was at his side for over a week, circling and circling. Some other days he’d head off to the forts and stand centre stage, walk the alts to reach the old man-built defences, and many times head out the rocks to catch the flower-like fossils in his curious lens. That made sense. But why haunt the abandoned? What are you after, I’d ask myself, then one morning there was a knock on my door.

My car has broken down, could you be my cabby for two days, Miss Jennifer? he asked.

Certainly Jack.

I got into the Ford, and he sat in beside me, his camera on his lap, and the haversack at his feet. I turned on the engine.

Where are we for? I asked.

How about above the valley?

Fine.

And so we headed up the road below the mountain on the northern side of the lake. On the way he jumped out and helped himself to a few strands of the white flowers of wild garlic. The smell filled the car when he sat back in. We passed lines of lived-in houses, some thatched, all looking the same way onto the waters below. Above them a couple of streams scored an old path down the cliffs. Cherry-blossom trees shook their wings.

And so began the procedure. Every few hundred yards or so he’d make the sharp request as he’d spy another emptiness. We’d stop suddenly and awkwardly. Then he’d step out to take shots of the ivy-covered walls of roofless ruins, the old blue and yellow doors locked by chains and the darkness floating beyond the old window ledges.

At one old ruin fresh daffodils were shooting up among the debris in the garden.

Mortality is rife, he said, as he caught an image of the flowers.

After each photograph was taken he’d study the snap, tip his chin off the back of the hand that held the cam

era and look closely at the place in question.

Maybe, he’d say. Maybe.

We shot up a side road where he tried the front door of another deserted house – whose tiled roof was still intact in places – but could not open it. He went round the back and was gone for maybe ten minutes.

Come here, he said, emerging from behind.

I followed him and found he had the back door open. He led me in to the middle room. Underneath a window to the side of the front door sat an old grey wooden piano and across the top lay a huge torn mattress and eight blue cushions. I hit the keys. There was no sound.

Can you hear the music? he said.

I can, I said.

Play another tune, he said, and he watched me stroking the silent notes.

He looked fondly at the gutted armchairs, said something to himself, and a look like aggression came over his face as he smiled.

How did they get a piano up here, back then? he said. The past is like a herd of deer.

We stepped out, he pulled the back door closed, and stood a while, wondering.

A girl in a motorised wheelchair went by with a small dog on a lead.

Off again.

We arrived at what might have been a forge, then on to a deserted post office, an old RIC barracks, a deserted farmhouse with a dog barking out of one of the top broken windows at the tulips and mayflowers sprouting below.

A big house makes you lonesome, he said. That place reminds me of my grandmother’s home, he said, she lived alone with a dog, and when she was in her seventies she committed suicide.

Dear God.

I should keep my mouth shut. The past has a lot to answer for.

Next we headed to a lonely, empty, big cement-block building out on the main road. It had eight glassless crucifixes on the windows looking in on the dark. That looks like an old school, said Jack. Crows waddled across the tarmac. I parked by a gate into a field across the way and this time he did not try to enter the premises but took pictures from all sides on the road, nursing the lens with steady fingers.

I have been here before a few times, he said.

As the cattle watched me I began to imagine him imagining the kids arriving for the Irish class. Maths. Religion. Sonnets. He went to his knees, and strips of wet hair crossed his bald head. At last he sat in and said in a boy’s voice, I have just been talking to a Miss Buckley and a Master Coyle. Oh yes! Study my dears, they said.

And be a good boy.

I will.

Off we go.

As we drove round the lake the waves stuttered as mists flew over.

This valley is renowned for rain, he said.

All of a sudden there was a rap of hailstones on the windscreen.

Ah Mother Nature can be very articulate, he said.

Then it was up a side road to another deserted cottage on the side of the mountain. He tried the door and it opened. He disappeared inside and was gone for some time. Up above sheep climbed the sheer side of Ben Bulben and hung there like markers. Old paths crossed over. Down below tractors passed with piles of the first cut of grass in their trailers. When he stepped out he was shaking his head and said Look! and he showed me the photographs in the camera, all in black and white. The first shot was taken from inside a room in the house and was aimed facing a window – through the old wooden crucifix that once held glass panes – that looked down on a steep dangerous fall to the valley and the lake below.

Now look at these, he said.

In the next appeared a kitchen table, with a bottle of Jameson whiskey – quarter full – sitting mid centre; then two chairs facing each other, an old metal ashtray and finally an Irish Independent newspaper from years back. We walked in and looked at the scene.

What do you make of that?

He lifted the newspaper, gone wet and black at the edges, with the print slipping into the unreadable, and read out the wandering headline concerning Vietnam, and then placed it back exactly where it had been. As we headed outside to the car a farmer driving black and white sheep and newly born lambs appeared on the lane.

Hallo. Not too bad a class of a day, he said.

We’ve just looked inside the cottage, said Jack.

Oh yeh?

Just taking photographs.

I’m sure the Bradys wouldn’t mind.

I’m glad to hear it. Did you ever see that bottle of whiskey?

No, not me. I have never once stood in that house since they’ve gone. I couldn’t. I just heard the story from neighbours. The brothers took off for America, back in the sixties. The hired car came, and off they went leaving everything behind exactly as it was. They was great in fairness to them. Aye and that house has been empty a long time since then.

Jesus Christ.

And there’s no relations in the area. One day the boys might come back. So there you go, good luck folks, take care, and he headed on down with the sheepdog racing and circling at the front.

Now, said Jack, history is a password.

Off we took again through another fall of hailstones and this time headed for an organic café for a bite to eat. On the way we passed a graveyard and he stared at the tombstones. Tranquillity can be very noisy, he said, there’s always a war in another land. At the car park an old lady sat on her own in the passenger side of a jeep slowly feeding light-green rosary beads through a finger and thumb. Jack got out, waved to her and took off his wellingtons and lifted a pair of white shoes out of his bag, then off came the jacket and on came a yellow jersey.

We had fish soup and scones, and he ate his ice cream like a child, all tongue and suck. Before we left he ordered two salad sandwiches for takeaway.

When we got back to the car the white shoes and jumper came off and he went into his old gear.

Will you drive me back to the piano house? he asked.

Of course. Could you put on your belt?

Oh dear.

We took off back along the same path, past the school and up the side road, and when we reached the grey debris he stepped out with his bag and his camera, pulled a fifty from his pocket and handed it to me.

I have a favour to ask you, he said.

Go ahead.

Will you collect me in the morning?

Sure thing.

Well, good luck!

What do you mean?

You can collect me here.

What?

Yes here.

Here? I thought you meant back at your house.

No here! I’m going to stay for the night. I will have to wait till after midnight before I sleep. You see I never go to bed on the same day I got up. And when I get up tomorrow I’ll head for school, and don’t you worry, I have all I need, even a sleeping bag, and he headed round the back with a wave.

Jack, are you sure? I shouted.

I am! came the distant call from someone I could not see.

I drove off filled with guilt past yellow piles of whins and forsythia. I stopped the car and thought can I really leave him there, then went on. I collected the pair of kids in Bundoran, an hour late, and on the way home I began to look at ruins I had never looked at before. My eyes wandered across the fallen walls, broken sheets of asbestos, crunched pillars, old lovers, black windows, shattered little iron gates, the tree shooting up alongside the chimney through where the roof once was.

Ma, keep an eye on the road, said David.

Sorry.

I thought of Jack all that night. In sleep I lost my way; then I dreamed I was carrying a friend’s baby in my arms. I found him, or he could have been a she, when I entered a small theatre with infants on stage. Inside the front door to the left was a medical room for training in folk. They were all in long grey gowns. It was here I found the babe. I set off down the town, and it was near my destination that I got the first bite on the edge of my palm. The babe held it tight with his teeth for nearly half a minute.

Then a few minutes later came the bites on two of my fingers.

I handed the child over to the mother

, and then an old businessman took my arm. He’d take my elbow again and again as we started walking round the strange town, and as we did so his head began to droop forward dangerously, and suddenly sometimes he’d go face down from the waist forward.

And no passers-by would help.

At last he straightened up and went on. I woke and wondered, and next morning drove off at nine o’clock to the piano house, lost my way, and started going round in circles. At last I found the correct route.

I knocked on the front door.

Hallo! I called. There was no reply.

I knocked on the back.

Jack!

Again no answer. I pushed the back door in and it swung open on a single hinge. The two rooms were empty and there was not a trace of his gear. Not a sign of anyone. A pile of dust sat in a corner by an old sweeping brush. He had been cleaning up. Jack! I screamed. I began to get that ghostly feeling. The piano sat silent again. Panic set in. I listened to him say he was going to stay in the piano house. Now what had happened? I heard him say And get up for school. I leaped into the car and drove down to the old ruins, pulled in at the gate and stepped out opposite the huge dark inside the eight windows.

Jack! I called.

An ass in a field behind me roared. All of a sudden out of one of the black windows of the old primary school came the haversack thrown like a schoolbag, then with the camera round his neck Jack appeared at another window and waved, disappeared, then reappeared out through a door in the side of the building.

You’re early, he said.

Good morning.

Sorry about that, missus, I was about to head back above to meet you.

Okay Jack.

We climbed into the car.

I’m afraid Miss Buckley and Master Coyle were not present there this morning, he said.

No?

No. Reality is more complex than the imagination. Look!