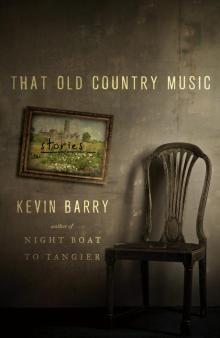

That Old Country Music

Kevin Barry

ALSO BY KEVIN BARRY

There Are Little Kingdoms

City of Bohane

Dark Lies the Island

Beatlebone

Night Boat to Tangier

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Barry

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Canongate Books Ltd., Edinburgh, in 2020.

www.doubleday.com

doubleday and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Several stories previously published in the following publications:

The Irish Times: “Roethke in the Bughouse” (December 29, 2015) and “Who’s-Dead McCarthy” (January 1, 2020); The New Yorker: “Ox Mountain Death Song” (October 22, 2012); “Deer Season” (October 3, 2016); and “The Coast of Leitrim” (October 8, 2018); “Toronto and the State of Grace” was originally collected in Sex and Death: Stories, edited by Sarah Hall and Peter Hobbs, published by Faber & Faber, Limited, London, in 2016.

Excerpt from The Piano © Jane Campion and Kate Pullinger, 1994, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Cover photographs: chair © conrado / Shutterstock; painting © shutterupeire / Shutterstock; frame © worker/ Shutterstock; landscape © Feifei Cui-Paoluzzo / Moment / Getty Images

Cover design by Michael J. Windsor

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barry, Kevin, 1969– author.

Title: That old country music : stories / Kevin Barry.

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020012308 (print) | LCCN 2020012309 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385540339 (hardcover) | ebook ISBN 9780385540346

Classification: LCC PR6102.A7833 A6 2021 (print) | LCC PR6102.A7833 (ebook) | DDC 823/.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012308

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012309

Ebook ISBN 9780385540346

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For Lucy Luck and Declan Meade

I think that the romantic impulse is in all of us and that sometimes we live it for a short time, but it’s not part of a sensible way of living. It’s a heroic path and it generally ends dangerously. I treasure it in the sense that I believe it’s a path of great courage. It can also be the path of the foolhardy and the compulsive.

—Jane Campion

Contents

The Coast of Leitrim

Deer Season

Ox Mountain Death Song

Old Stock

Saint Catherine of the Fields

Toronto and the State of Grace

Who’s-Dead Mccarthy

Roma Kid

Extremadura (Until Night Falls)

That Old Country Music

Roethke in the Bughouse

THE COAST OF LEITRIM

Living alone in his dead uncle’s cottage, and with the burden lately of wandering thoughts in the night, Seamus Ferris had fallen hard for a Polish girl who worked at a café down in Carrick. He had himself almost convinced that the situation had the dimensions of a love affair, though in fact he’d exchanged no more than a few dozen words with her, whenever she named the price for his flat white and scone, and he shyly paid it, offering a line or two himself on the busyness of the town or the fineness of the weather.

“It’s like France,” he said to her one sunny morning in June.

And it was true that the fields of the mountain had all the week idled in what seemed a Continental languor, and the lower hills east were a Provençal blue in the haze, and the lake when he lowered himself into it was so warm by the evening it didn’t even make his midge bites sting.

“The heat,” he tried again. “Makes the place seem like France. We wouldn’t be used to it. Passing out from it. Ambulance on standby.”

His words blurted at the burn of her brown-eyed stare. She didn’t lose the run of herself by way of a response but she said yes, it is very hot, and he believed that something at least cousinly to a smile softened her mouth and moved across her eyes. He had learned already by listening in the café that her name was Katherine, which was not what you’d expect for a Polish woman but lovely.

At thirty-five years of age, Seamus Ferris was by no means setting the night on fire at the damp old pebbledash cottage on Dromord Hill, but he had no mortgage nor rent to pay, and there was money from when the father died, a bit more again when the mother went to join him, also the redundancy payment from Rel-Tech, and some dole. He had neither sister nor brother and was a little stunned at this relatively young age to find himself on a solo run through life. He had pulled back from his friends, too, which wasn’t much of a job, for he had never had close ones. He had worked for eight years at Rel-Tech, but more and more he had found the banter of the other men there a trial, the endless football talk, the foolishness and bragging about drink and women, and in truth he was relieved when the chance of a redundancy came up. He had the misfortune in life to be fastidious and to own a delicacy of feeling. He drank wine rather than beer and favoured French films. Such an oddity this made him in the district that he might as well have had three heads up on Dromord Hill.

He believed that Katherine, too, had sensitivity. She had a dreamy, distracted air, and there was no question but that she seemed at a remove from the other mulluckers who worked in the café. The way she made the short walk home in the evenings to the apartments across the river in Cortober again named a sensitivity—she always slowed a little to look out and over the water, maybe to see what the weather was doing, perhaps she even read the river light, as Seamus did, fastidiously. He could keep track of her route home if he parked down by the boathouse, see the slender woman with brown hair slow and turn to look over the water, and it was only with a weight of reluctance that she moved on again for home.

In the sleepless nights of the early summer his mind ran dangerously across her contours. He played out many scenarios that might occur in the café, or around town, or maybe on a Sunday walk through the fields by the lake. It was a more than slightly different version of himself that acted his part in these happy scenes: Seamus as a confident and blithe man, but also warm and generous, and possessed of a bedroom manner suave enough to ensure that the previously reticent Polish girl concluded his reveries roaring the head off herself in gales of sexual transport. Each morning when he awoke once more in an aroused state—there was no mercy—it was of Katherine from the café that he thought. She was pretty but by no means a supermodel, not like some of the Eastern Europeans, with their cheekbones like blades, and as Seamus was not himself hideous, he felt he might have a chance in forgiving light. All he had to do was string out the few words right in his mouth.

He was in the café by now four or five times a week, and she was almost always on. The once or twice she hadn’t been were occasions of crushing disappointment, and he’d glared hard at the mulluckers, as they bickered and barked like seals over the trays of buns and cakes. Even the hissing spout of the coffee machine was an intense annoyance when Katherine wasn’t there. Along with its delicacy, Seamus’s mind had, too, a criminal t

endency—this is often the way—a kind of native sneakiness, though he would have been surprised to have been told this. The café’s toilet was located right by the kitchen, and Seamus could not but notice what looked like a rota pinned to the back of the kitchen door. Catching his breath one Monday morning, he reached in with his phone and took a photograph, and in this way he had her hours for the week got. Also, her full name.

* * *

Katherine Zielinski she was called, and he wasn’t back in the van before he had it googled—it might be unusual enough inside quote marks to give quick results, and indeed within seconds he was poring over an Instagram account in her name. The lovely profile picture confirmed her identity—it was his Katherine all right, with her fourteen followers. She had posted only six times, six images, going back to the January previous, and relief flooded through him like an opiate when he found no photos of a boyfriend nor of a baby. It was something more intense than an opiate that went through him when he studied the most recent post, which was from the weekend just gone. It was of Katherine’s right hand resting on the bare thighs revealed by her shortish denim skirt, and in the hand she clutched a slim box set—it was “Tales of the Four Seasons,” four films by Éric Rohmer. Her accompanying caption read, “Goracy weekend.”

It was a swift job to go to Google Translate with that and find that it meant, merely, “Hot weekend.” She had humour as well as taste, it appeared, though in truth Seamie Ferris wouldn’t be putting Rohmer at the top of the league in terms of the French directors; he would in fact rate him no more than highish in the second division, but at least he might be able to argue to her a rationale for this. Her knees were lovely and brown, though possibly a little thickset, but as it was a case of mother fist and her five daughters up in the pebbledash cottage, this was not a deal-breaker.

He spent time with the other images. He tried to decipher them or, more exactly, to decipher from them something of her character. Her only other personal appearance was in a blurry selfie that showed her reflection in a rain-spattered windowpane and that was suggestive, somehow, of Katherine as a solitary. There was a poor vista of the river from the bridge at evening. The rest of the images were reposted from other accounts—someone’s pencil drawing of Sufjan Stevens; a cityscape that might have been of the Polish winter, its streetlights a cold amber; and, finally, a live shot of Beyoncé at a concert in Brazil in the stance of some new and utterly undefeatable sexual warrior. These images spoke to Seamus Ferris, in a low, insistent drone, of a yearning he recognised, and he felt that now he should end his playacting and confide his feelings to the woman.

The idea sent him into a foetal huddle on the couch, his back turned to the hot afternoon sun that poured through the window to show up the cottage in its bachelor meanness. The strangest thing he had learned while alone in his mid-thirties was about the length of the nights. They were never-fucking-ending. They opened out like bleak continents. They were landscapes sombre and with twisted figures. He lay there and flopped and muttered on the couch until the darkness again fell on Dromord Hill and the extent of the night shamelessly presented itself. He felt backed into a corner. He would have to ask her out. The worst that could happen was a refusal and the subsequent embarrassment of that, but there are worse things than embarrassment, he had learned, in the night, when his mind wandered across such things.

In the auditing of the night a plan had been laid down. He would raise the question on a Thursday morning, and so he had not shaved since the Monday—this provided a shadow of interest across what was in truth a weakish jawline. He scratched at the stubble helplessly as he picked at his scone, sipped at the cooling coffee. His stomach tumbled and spoke. He would leave it until he was ready to depart, and if he was refused at least he would be out the door and could go and fuck himself into the Shannon. He was about to stand and make grimly for the counter—he felt like a man heading off to be shot—when she stepped out from behind it and for absolutely no good reason came to saunter around his table, looking out at the rain that as sure as Jesus had returned to make another wet joke of the summer.

“Back to the usual,” she said.

“You’d nearly do away with yourself altogether,” Seamus Ferris said.

“What do you mean?” she said.

“Nothing by it,” he said. “Do you want to go out with me sometime?”

“That will be fine,” she said. “When is this happening?”

* * *

He believed now that they were in telepathic contact with each other. She must have known and read his intention. She must have known, too, that he had sensed her likely compliance. This was how fatedness worked, how love discovered itself. In the long three days, the endless three nights that led up to their Sunday meeting, he attempted to send mental messages down Dromord Hill and across the slow meander of the river. The content of these messages was even to himself uncertain but had to do with ardency and truth.

The Sunday of their arrangement came up to dense clouds and a heavy mugginess. He went to the toilet five times in the morning and took Imodium against the thunder of his insides. Attraction as physical catastrophe was not exactly news to Seamus Ferris. He had been besotted before. Always it was with slightly humourless-looking women who appeared to be in a condition of vague disbelief about the world. If involved in any level of romance, he was given to lurchy moves and hot declarations, and always in the past he had scared the women off within a few dates. He had not had anything even close to sex for three years. With his Katherine he vowed that all would be different.

He met her by the bridge at three—the arrangement was for a spin in the van.

“Have you ever been to the coast of Leitrim?” he asked her, unpromisingly.

“No,” she said. “It has a coast?”

“The coast of Leitrim,” he said, “is four kilometres long. Which is in fact the shortest length of coast belonging to any county in Ireland.”

“Now I know,” she said.

“I mean barring the landlocked counties,” he said.

“Okay,” she said.

As he drove and they went through the rituals of small talk, he tried to communicate with her directly, too, without words, by way of pure mental focus. He tried to let her know that he needed her badly and that in his own modest way he was a prospect. He told her that he had a house that wanted work but was situated well. There were few bills. There was more than an acre of land to grow vegetables and flowers, and already he had begun this garden. It could be beautiful yet, he said. As they drove out of the Cortober side of town, a parade of drunken women skittered towards the bridge in glittery cowboy hats and stretch-nylon skirts, with bottles of Skinny prosecco to hand and in their eyes the dissolute, the haunted look of a three-day hen at its fag end and emblazoned on their tight-fitting t-shirts the legend “MOHILL PUSSY POSSE,” and with something already close to love he turned to see the tip of Katherine’s nose rise to match his own disdain.

“Why would they do this to themselves?” Katherine said.

“There’s a sickness around the place,” Seamus said.

A rare thing occurred then in the van as it hoovered up the N4—a companionable silence. To his awe he found that they were perfectly comfortable with each other and they didn’t even have to try.

* * *

The coast of Leitrim sat under a low rim of Atlantic cloud. The breeze made the cables above the bungalows whisper of the Sunday afternoon’s melancholy. The waves made polite applause when they broke on the shingle beach. She told him that she came from Stalowa Wola, a small city in the south, and that she could not see herself going back there. His heart soared.

“Is there no work?” he said.

“Not much but it’s not that. It’s more that my family is there and that makes everything too…”

She struggled for the word.

“Close?” she tried.

“Clammy,” Seamus said. “Families can be like that. Give a clammy feeling.”

“Clammy?”

“Like a warm feeling but not in a good way,” he said. “Sweat on your palms and at the base of your back. A nervous-type feeling.”

“You’re funny,” she said.

“Thanks be to fuck for that,” he said.

“But yes,” she said. “Clammy.”

They walked the shingle beach. He told her as much as was bearable to tell about himself. He had gone to college in Galway to study French and business, but he had not finished his degree. He was not by his nature a finisher of things, he said. He had never said this before or really even thought it and it was a surprise to him. It was all coming out before the soft lashes, the stare. He had worked for years in a factory, he said, and lived at home. (The way an eternity of cold dread could be packed into a single line.) Somehow he had not had the impulse to travel. He had not known what he was looking for, if anything at all, he said, until he turned from the bog road into the clearing on the wooded slope of Dromord Hill and found there the pebbledash cottage of the old uncle he had barely known, and he had recognised the place at once as his home.

“I would have been brought there as a child,” he said. “I remember being taken up there after I made my Holy Communion. He gave me two sausage rolls for it.”

“This is a custom?”

“No, usually people give you money, a tenner.”

Their talk came in odd spurts and the trudge of their feet went slowly across the shingle but the ease they found outside and around the talk was soft magic. Here she is for me, he thought. Here is the woman at last that I can be alone with.