Arundel

Kenneth Roberts

ARUNDEL

ARUNDEL

By

KENNETH ROBERTS

TO

G. T. R.

Copyright © 1930, 1933 by Kenneth Roberts. Reprinted by

arrangement with Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

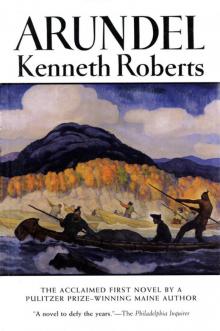

Cover illustration: The Bateaux on the Dead River, by N. C. Wyeth.

Private collection. Used by permission.

Maps by Jane Crosen.

Printed and bound at Sheridan Books, Inc.

Color separation by High Resolution, Camden, Maine

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Roberts, Kenneth Lewis, 1885–1957

Arundel / by Kenneth Roberts

p. cm.

ISBN 987-0-89272-364-5

1. United States History—Revolution, 1775–1783—Fiction. 2. Canadian Invasion, 1775–1776—Fiction. 3. Arnold, Benedict, 1741-1801—Fiction. 4. Maine—History—Revolution, 1775–1783—Fiction. I. title

PS3535.0176A8 1995

813′.52—dc20

95-15964

CIP

PROLOGUE

I

HAVING no wish to pose as a man of letters, but earnestly desiring to see justice done, I, Steven Nason, of the town of Arundel, in the county of York and the province of Maine, herein set down the truth, as I saw it, of certain occurrences connected in various ways with this neighborhood.

Erroneous tales have been told of exploits that I, together with the notorious Cap Huff, have performed, and concerning powers I am supposed to possess.

My relations with the Indian girl Jacataqua have been misrepresented. There have been doubts cast on the loyalty of Natanis. There has been loose talk, among armchair warriors, of how Colonel Enos left us in the wilderness, and overmuch gabble among old wives about my search for Mary Mallinson and the manner in which I settled my affairs with Henri Guerlac de Sabrevois.

Above all, because of the lamentable occurrences at West Point, the countryside is filled with men of mighty hindsight who speak with scorn of Colonel Arnold, whose boots they were not fit to clean, and belittle or ignore the expedition to Quebec. That achievement, to my way of thinking, is unequaled in all the many histories of campaigns that my grandson has obtained for me from the library of Harvard College, and that I have read carefully during long winter storms, when the breakers roar on the ledges and beaches, and the pines behind the summer camping place of the Abenakis are frosted with snow, calling to my mind the gables of lower Quebec, and the bitter days through which we lay and watched them against the snow-plastered cliff beyond.

I have small skill in writing, being more fitted for wood trails than for a knee-hole desk, and my hand better shaped for handling an axe than for anything as delicate as a pen. Nevertheless I am constrained, as Colonel Arnold was given to saying, to have a shot at it, so to set these matters right.

In so doing I accept the judgment of my father, who was wise in woodcraft, and somehow versed in the ways of mankind at large, though he had traveled little except to Louisbourg on Cape Breton, where two thousand of our colonists drank untold quantities of rum and captured the city from the French. It was from Louisbourg that he brought home as booty our silver sugar bowl and the large white pitcher with the raised figures of dancing countrymen around it: the same pitcher we now use for cider on a winter’s night, when the ice cakes click and scrape on the sand beyond our garden at the mouth of the Arundel River.

If you have something to say, my father held, say it without thought of anything except the truth. If it is worth saying, those who read it will not complain. If it is not worth saying, then there will be few to read it, and fewer still to vex you with complaints.

Therefore I am hopeful that those who come upon this book will disregard its faults and read it for the things that seem to me worth saying.

II

The way in which our family came to Arundel is a matter I set down, not to boast of my own people, since we have been simple farmers and smiths and innkeepers and soldiers and sailors, always; but so my great-grandsons may know what manner of folk they sprang from, and feel shame to disgrace them by taking advantage of the weak or ignorant, or by turning tail when frightened, which they will often be, as God knows I have too frequently been.

My grandfather, Benjamin, was a blacksmith and gunsmith in the Berwick section of the town of Kittery, his grandfather Richard having come there in 1639 from Berwick in England.

In those days the frontiers were steadily pushing eastward and northward; and to the eastward of Kittery lay the town of Wells, gradually growing in size, though populated by shiftless and poverty-stricken folk, dwelling in log huts without furniture, and constantly at odds with the Indians.

In order to obtain a blacksmith, the town of Wells, in 1670, sent to my grandfather a paper, which I still have in my small green seaman’s chest, guaranteeing him two hundred acres of upland and ten acres of marsh if he would settle in Wells within three months, remain there for five years, and do the blacksmith work for the inhabitants for such current pay as the town could produce. This my grandfather did, albeit he spent less time at blacksmithing than in hunting with the Abenakis, by whom he was liked and trusted, as was my father to an even greater degree. It is my opinion that he was justified in spending little time in his smithy, since the only current pay the town could produce was promises that were never kept.

My father, then, was born in Wells; and when he had reached the age of seventeen, he was skilled in the arts of the blacksmith, the gunsmith, and the hunter. He had, furthermore, been blessed with nine brothers and sisters; and wishing to enjoy the pleasures of married life without falling over a child not his own whenever he turned around, he looked about and took thought for the future.

Three leagues to the eastward of Wells, along the hard white crescent-shaped beaches so plentiful in the southern portion of our province, is the Arundel River. This is a narrow river, but deeper than most of those that cut across our beaches. Therefore it has a bar farther out at sea, less easy to pass than many river bars, so that travelers view it with trepidation.

My father frequently hunted and fished near its mouth, going with friends from the Webhannet tribe of Abenakis, chiefly with young Bomazeen, the son of the wise sachem Wawa. I have heard him say he took more pleasure in the place than in any other section that had met his eye. Most men say the same thing concerning their homes; but few, to my way of thinking, have the reason for saying it that my father had.

In the spring there are quantities of salmon running upstream, easy to take with a spear because of the narrowness of the river bed. When the salmon are finished there are fat eels lying in the current riffles at low tide, so thick that in an hour one boy with a trident may fill a barrel, which is a feat I have frequently accomplished, being addicted to smoked eel with a gallon of cider before meals, or during them, or late at night when the nip of autumn is in the air, or indeed at any time whatever, now I stop to think on it.

After the eels are gone the green pollocks come up the river by the millions, fine fish to salt and dry, especially in a manner discovered by my father, which ripens their flesh to a creamy consistency, uncommonly delicious.

After the pollocks come small spike mackerel; and between seasons, when the tide rises on the bar, beautiful flat flounders lie in the sand with eyes popped out, amazed like, to betray their presence.

In the autumn come deer to paddle in the salt water, and hulking moose deer, and turkeys occasionally; also teal, black ducks, and Canada geese in long lines and wedges; while always our orchards and alder runs are filled with woodcock and that toothsome but brainless bird, the partridge, who flies hastily into a tree at the approach of a barking dog, and stays there, befuddled, until the dog’s owner walks up unno

ticed and knocks him down.

In the late summer, and in the spring as well, there are noisy flocks of curlews and yellow legs and plovers, wheeling above the sands in such numbers that a single palmful of small shot will kill enough for one of the juicy game pies my youngest sister Cynthia takes such pride in making and I such delight in eating.

At the mouth of the river my father found an oblong piece of farmland, set off by river and creek and beach into an easily defended section, and presenting opportunities for trade and a modest income. Since there was no white man dwelling thereabouts, probably because of the numbers of Indians who came in the summer to fish and to lie in the cool sea breezes, he took it for his own; and the Indians were content, since he traded honestly with them.

On the seaward side of our farm is a smooth white beach, half a mile in length, shaped like a hunting bow. This beach appears to face straight out to sea; but because the seacoast swings outward near this point the beach in reality faces south, toward Boston. Thus the hot winds of summer, which are southwesterly, blow in to us across the ocean, and so are cool and pleasant.

At the western end of the beach is a tumbled mass of rocks, fine for the shooting of coot or eating-ducks in spring or fall, or for capturing coarse-haired seals for moccasins, or for taking the small salt water perch which we call cunners. These we take at any season, whenever we crave the sweetest of all chowders. I have eaten the yellow stew that Frenchmen in Quebec call boullabaze, or some such name, and brag about until their tongues go dry; and I say with due thought and seriousness that, compared with one of my sister Cynthia’s cunner stews, made with ship’s bread and pork scraps, a boullabaze is fit only to place in a hill of green corn to fertilize it, if indeed it would not cause the kernels to grow dwarfed and distorted.

At the eastern end of the beach and of our farm is the river mouth; and directly across the river the rocky headland of Cape Arundel pushes out to sea. Two hundred yards upstream a generous creek bears back to the westward, parallel to the beach, into a long salt marsh.

Thus our farm is protected on the south by the ocean, on the east by the river, on the north by the creek, and is open only on the west, in which direction lie the settlements; so with slight precautions one need fear no attack from any ordinary force of enemies. Even on the side toward the ocean my father found protection from French raiders; for offshore is a semicircle of reefs, hidden at full tide in a calm sea, but raising a smother of foam and roaring regiments of breakers when the wind blows from the east or northeast.

These ledges, covered with tangled growths of seaweed, cause the delicious odor peculiar to these parts in summer; for the prevailing winds, blowing across them, bring to shore a perfume that seems to come from the heart of the sea—an odor I know of in no other place, though there have been Frenchmen pass through here who declare the same heartening smell may be found on the coast of Brittany. This may be true, though I would liefer hear it from an Indian than from a Frenchman if I had to depend upon it.

The truth is I love the place; and if I seem to talk overmuch of it, it is because I would like those who read about it to see it as I saw it, and to know the sweet smell of it and to love it as I do.

On the highest point of this farmland my father, at the age of seventeen, with the assistance of my grandfather and Bomazeen, the son of Wawa, and a carpenter from York and Abenakis from the camp across the creek, built a sturdy garrison house out of logs.

From the back door he looked down on the creek and the glistening dunes that border the river mouth and the beach, and on the brown rocks of Cape Arundel, over which the sun came up to warm him at his early morning labors. From the front door he saw the sweeping crescent of sand, and the reefs with creamy breakers gamboling around and over them, and the flat salt marsh to the westward; and far away, beyond the beach and the reefs, he saw what I see today and what you, too, may see if you will come to Arundel: the blue expanse of Wells Bay with the gentle slopes of Mt. Agamenticus behind it; and to the left of Agamenticus the mainland of Wells and the cliffs of York, small and blue above the water, and soothing to the eye.

It was a luxurious house by comparison with those roundabout at that time; for it had floors of boards, and bedsteads in the sleeping rooms, with mattresses resting on cords and stuffed with corn husks. In each room was a chest and a chair, and in the kitchen a table and a carved court cupboard and stout chairs. The place was a boon to weary travelers; and it was surprising how often those who passed that way were overcome with weariness at our front door.

Beside the garrison house was a smithy where my father could ply his trade when occasion rose, and sheds for horses, the whole stockaded against hostile Indians. On the river bank was a skiff for ferrying men and horses across; and the town had given my father, in consideration for his living there, the sole right to conduct a ferry at the river’s mouth.

III

Of my father’s first wife I know little. She came from Wells and was a melancholy female, given to upbraiding my father for going alone into the wilderness during the winter months. He did this in order to trade with the Indians for beaver skins and to seek out paths and locations for Sir William Pepperrell and Governor Shirley and for the Colonial Government, which knew less about the country to the north and east than a rabbit knows about fish.

Although my father never said so, I suspect he went into the wilderness to escape his first wife, and so formed the habit of roaming in the woods and living in wigwams for weeks on end—a habit from which he never recovered.

She was a sickly woman, troubled with indigestion, and bore my father no children, which was a cross to him. She was intemperate with the Abenakis, frequently attacking them with her brush broom when they came into the kitchen uninvited, as Indians always do unless at war, when they hide in bushes near the house and wait, usually in vain, for someone to stumble over them and be killed. This, too, was a source of trouble to my father. Indian wars have started with no greater provocation; and for weeks after his first wife had beaten an Indian with her brush broom he never left home without fearing that on his return he would find the house burned down.

She was finicky and would allow no servants to assist her, although my father, having accumulated a respectable amount of money through ferrying and the sale of beaver skins, would gladly have obtained one for her. This was the more annoying because the house was like to be full of travelers seeking a night’s hospitality, to say nothing of the soldiers stationed there at any rumors of Indian troubles, so that his first wife was perpetually complaining and groaning about the work to be done, and there was no peace in the house.

Worst of all, she was a bad cook. Perhaps I should not set it down here, but it was a good thing for her and a good thing for my father and a good thing for the Indians and certainly a good thing for me, since without it I would never have been born, when she died of a consumption.

My father had little leisure for grieving after she had gone, even though he had been so inclined.

Settlers constantly increased, and hostile Indians from the north came more frequently to harass them; so the garrison house was too small to harbor those who sought refuge and provender. Therefore my father built a sawmill on the creek behind the house; and in this he sawed the King’s pines that stood on his land; for in common with many in our province, he believed the King had no right to trees standing on a settler’s land, even though they were the King’s by law. Holding this law to be a foolish one, he broke it whenever he could break it unobserved, as is the custom with all of us. From these King’s pines came boards forty inches wide, as free of knots as mahogany from the Sugar Islands.

With them he enlarged the garrison house, so that forty persons might live in it in comparative comfort. He covered the logs with narrow overlapping boards and erected a symmetrical ell on each side, and made a new room out of our old kitchen, a gathering-room cool in summer and warm in winter. It had a fireplace so large that six people might sit within it on each side of the fire,

as fine a place as ever I saw for drinking buttered rum on a cold night provided the drinker is careful, as one must always be, not so much with the rum as with buttered rum, for it is the butter, as all drinkers of this concoction know and say, that wreaks the harm. And so, when the fireside drinker must be hearty with buttered rum until the butter makes him topple, it were well he took thought to topple sidewise or backward rather than slither forward into the fire.

The walls within were sheathed with broad boards of pumpkin pine with the edges shaved thin and overlapping, so that no crack could appear, howsoever the boards might shrink; and my father obtained the services of two shipwrights, and had them make small oval-topped tables, which might be drawn before the fire and gripped between the knees by one who wished to come to close quarters with a juicy black duck or a steaming clam chowder.

From the town he had a license as an innkeeper and a permit to dispense spirituous liquors; and all who came by the beaches stopped at the inn. In the town of Wells he secured a black woman named Malary, who had been freed from slavery along with six other slaves; and Malary was held in esteem for her cooking, in especial her manner of baking beans, a trick that has been nobly acquired by my sister Cynthia.

All this I know from what my father told me in my boyhood evenings; and yet how little it seems, now, that I know of him and of those times. Almost anything in the world is readily forgotten after ten years. After the passage of fifty years a happening so fades into the mists of antiquity that little is known about it except by those who took part in it; and that little is mostly wrong. Of how my grandfather Benjamin lived and what he ate and what he wore I know next to nothing, nor do I know anything about my great-great-grandfather Richard, except that he was an ensign of Kittery in 1653, and one of three men to lay out the boundary between the towns of Kittery and Wells in 1655, because I have seen his name cut on the rock at Baker’s Spring. Of how he cooked his black ducks and prevented the curse of chilblains, and whether he escaped the cruel burden of rheumatics, and what he thought about certain passages in the Bible I must remain in darkness. Yet my great-great-grandfather, of whom I know so little, was at the height of his powers a mere one hundred years ago.