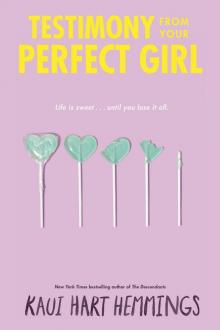

Testimony from Your Perfect Girl

Kaui Hart Hemmings

ALSO BY KAUI HART HEMMINGS

Juniors

The Descendants

House of Thieves

The Possibilities

How to Party with an Infant

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

Copyright © 2019 by Kaui Hart Hemmings.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hemmings, Kaui Hart, author.

Title: Testimony from your perfect girl / Kaui Hart Hemmings.

Description: New York, NY: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, [2019]

Summary: While their parents deal with a scandal, sixteen-year-old Annie and her brother, Jay, spend winter break with an aunt and uncle they barely remember, uncovering family secrets.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024212 | ISBN 9780399173615 (hardcover)

Subjects: | CYAC: Brothers and sisters—Fiction. | Scandals—Fiction. | Secrets—Fiction. | Family life—Colorado—Fiction. | Colorado—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.H46 Tes 2019 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024212

Ebook ISBN 9780698188426

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover art © 2019 by Samira Iravani.

Version_1

For my young adults: Eleanor, Leo, and Talcott

CONTENTS

Also by Kaui Hart Hemmings

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1

It’s an ordinary day and nothing is wrong.

I walk to my last class with this lie on repeat in my head. It’s the last day before Christmas break, and I’ve dressed accordingly. I’m still in my conservative style—black pixie pants and an Italian wool-blend turtleneck—but for a dash of festivity I put on red plaid flats and small, antique gold chandelier earrings.

I’m pretending to be absorbed in something on my phone, but am aware of people looking at me differently, in a daring—almost gloating—kind of way. During my previous class, even Mr. Koshiba, who usually loves me for my focus and quiet enthusiasm, wouldn’t look me in the eye.

Right on time, Mackenzie and her squad come around the corner, heading to Music Explorations. We exchange smiles. While I’m not in this rowdy, popular crowd, they’re still friendly to me. As freshmen, they assumed we’d be friends, since all our parents are friends, especially our mothers, but they soon found I’m not like my mother or my brother. I don’t like parties, I don’t like to drink—I’ve always been too busy with ice skating—and I take school seriously. I’m like my father: ambitious.

One of the squad members—Cee—is a friend. Her dad works with my father, so we hang out—mostly one-on-one. I can be dorky and relaxed with her, and vice versa. She’s not with them, I notice, which is odd. I tease her for being so tethered to these girls, as if she’d float away without them.

Mackenzie looks up from her phone, and something in her expression reminds me that I’m fooling myself. It’s not an ordinary day at Evergreen, and she knows it. This whole school, this whole town knows it. I lift my head a little higher, stand a little straighter.

She slows, and the other girls whoosh past like she’s a rock in a river.

“Hey,” she says. “Cee wanted me to give this to you.” She hands me my sweatshirt that I hadn’t planned on ever asking her to return. It’s her favorite—a gray cashmere hoodie. I don’t see why she couldn’t give it to me herself.

“Is she out sick?” I adjust my saddle bag.

“Sort of,” she says. I don’t ask more questions, not wanting to show my confusion. “How are you doing?” she asks.

I look around. “Fine? Why?” I shouldn’t have welcomed more conversation, and what is her motive for being concerned?

“Come on,” she says, in a quieter voice. “I know it must be hard.”

It’s then that I remember. A few years ago, her mom went to jail for tax evasion, but that’s hardly the same. My dad isn’t guilty, and he won’t go to jail. Her mom was a crook.

“It’s pretty typical,” I say. “In his line of work.”

“Totally,” she says.

Her parents were there at the opening, and I wonder if they bought in. I think back to the party where my dad announced the launch of Aria’s construction. He began his speech with I don’t ask myself how much I can make. I ask myself—what can I create? What kind of life can we erect for our children?

Afterward my grandfather, one of Genesee’s founding fathers, berated him, saying that erect and children should never be said in the same sentence, but still, I could tell he was proud of my dad. Dad was following in his footsteps (or, now, the Rascal path). He was continuing the developer tradition, but stepping it up, making condo units designed like custom homes. I’d look through the dreamy and sleek artist renderings, imagining myself living there on my own one day. The building would have a gym, wine cellars, concierges, a salon, a dog park, dining rooms, a movie theater—you’d never have to go anywhere for anything. You’d live in a beautiful bubble with people just like you.

“The worst is the pity,” Mackenzie says, and her face seems to tighten at a memory.

I know exactly what she’s talking about. Pity is insulting, embarrassing.

“And the way you just know people will talk about you as soon as you leave,” she says. “It’s, like, your story. But don’t worry. It wears off.”

Stop reassuring me, I want to say. Stop thinking we’re the same. Everyone at school must love this—t

he impeachment of royalty. I can’t wait until he proves everyone wrong.

“I’m not worried,” I say, tagging on a laugh. “My dad didn’t commit a crime. So . . . it’s not really the same.”

I can tell she’s offended, but I don’t care.

“Tell that to Cee,” she says, and walks away.

I immediately look at my phone as though it will supply an answer. What does this have to do with Cee? Yes, our dads work together, but they’re on the same side. They’re in on this together. I text her:

Speak up

Something we always say when we want to hear what’s what immediately, in its purest form. No BS. What’s up? Speak up. Let it all out.

By the end of the day, nothing comes up or out. Maybe she was too embarrassed to come to school and face her friends, but that doesn’t make sense, since she gave Mackenzie my sweatshirt to give to me. She’s angry about something that I did, and now I’m mad, too. Whatever she thinks, she’s got it all wrong.

2

I walk out of my bedroom to meet my dad in the living room at four thirty. Pictures of me and my brother line the hallway, black-and-white photos, all in white frames, capturing the (staged) moments in our lives. They’ve been taken by a professional photographer, Vincent, a man with a tropical accent who comes yearly, first week of October because a fall/winter card is classier, and barks out directions: “Tilt chin, smile, smile harder, smile not so much, jump in the air, laugh! You are so happy! You don’t know I’m here!”

Yes, we’re naturally wearing coordinated outfits, laughing at a hilarious joke no one told, and we don’t know you’re here taking pictures of our dorkdom.

When we were much younger, my brother and I enjoyed ourselves and the process. When we were laughing in the pictures, we were laughing in life. Now we stand still and grunt through various poses, then look at one another shyly afterward, as if we just participated in something lurid, which we did. We’re selling people the myth of our life.

Here’s my myth: I am polished, in control, above it all. I am wealthy, pretty, yet don’t care about my looks or the things I have. I only have a few friends, but I’m not lonely. I’m not funny, weird, or dorky. I am Annie Tripp.

Each year Vincent is less enthusiastic as well. He knows he’s complicit in the lie.

“Just grin a little so you don’t look like a tiger.”

“Put your arms around one another. You are brother and sister. You are family.”

When we are done with our photos, our parents join in so we can take our Christmas card photo, and this photo, year after year, reveals nothing about us. We are styled, we match, no one’s unique. My mom and I have the same hairstyles, soft, dark blond waves, having both been blown out and hot-rolled by Kat Pearson, my mom’s stylist. My dad and Jay are matching, too: brown hair parted to the side, chests puffed out, jaws clenched, laughing through their teeth until it’s over.

In last year’s card you can’t tell my mom is pregnant. She wanted to hide it for as long as possible, afraid she’d miscarry. In another, a couple of years before that, you can’t see Jay’s hangover or how sad we all are that my grandmother just died. You can never see how stressed I am from school and skating. All you can see is a girl who is confident, perhaps aloof, with a happy family, a beautiful home, a perfect, enviable life.

I walk down the hall, as if at a museum, and stop before this year’s Christmas photo. The dress code: jeans and white sweaters, good god. Sammy’s first card—he’s ten months old. My dad looks like a king. Even the signs of aging—the little pouches under his eyes, the forehead fissures—give him strength. You would never know from this year’s photo that he’s been wrongly accused of robbing people blind or that he’ll spend our winter break in a courtroom.

My brother walks out of his room. He looks like he’s just woken up.

“Jay!” I hear my mom call from downstairs. “Annie!”

“You always get called first,” I say.

“Because I’m older, and I’m meant to herd you.”

We walk down the staircase. Our parents sit in the living room in front of the fireplace. The wall of glass behind them makes it seem like the snow and forest are part of our space. My mom sits on the black leather chair next to the plush sectional. She looks so formal, like she’s about to give a presentation. My baby brother is in his ExerSaucer gnawing on his knuckle. I’m so glad he’s here, that he exists—one, because I love his fat face, and, two, so my mom can stop trying to have a baby. The fertility drugs made her wicked.

“Have a seat,” my dad says, gesturing to the couch. His face is pinched and cold. He usually looks like he’s waiting for the punch line of a joke even when he’s being serious. The sides of his hair are streaked with gray—they make me think of a road, which makes me think of riding with him on his motorcycle, my hands around his waist, holding on for dear life on the curves. I’d rest my cheek on his leather jacket. My mom would get nervous, but not that much when I think about it. I don’t know if she trusted him completely or didn’t have a choice, or didn’t want one. My mom takes care of their social lives.

Jay and I sit on opposite sides of the couch. I try my best to look composed.

Jay claps his hands together. “What’s up?”

I scoff. His attitude is so kiss-ass positive. Always so relaxed. It’s a man thing and I am a girl. I just hold on for dear life. Except I don’t. I know my dad. I know real estate. The difference is Jay and I can have the same things in life, but he won’t have to study.

My mom dabs at her shirt: boob-milk leakage.

“As you know, Dad will be in Denver for a while,” my mom says. “The attorneys think it’s best that I’m also at court. To show support. So we’ll both be going. We’ll stay at the Cheesman Park apartment.”

“Would it help if we were there, too?” I ask, and get a nasty look from Jay.

“No, sweetie,” my dad says. “It’ll be boring. You guys have a good break.”

My parents then stop and look at one another.

“You’re going to stay with Aunt Nicole and Uncle Skip while we’re away,” my mom says.

“What?” I ask. “Why?”

“That’s cool,” Jay says, most likely thrilled, since they live in Breckenridge and he can snowboard every day.

“Why can’t Jay and I stay here by ourselves? I can handle things just fine.” Better than you, I think.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “These are hard times, but we’ll make the best of it. This is all we can do.”

Really? I think. This is all we can do?

“Or, we can all just live together,” I say.

“It’s temporary,” my dad says. “The trial shouldn’t go on for long. A few weeks. If it’s longer, you may have to commute to school for a bit—”

“Commute? Why would we do that from Breckenridge and not Denver with you?”

“It’s going to be stressful,” he says, ignoring me. “Every day I’ll be prepping with lawyers. It’s best if you guys aren’t around all that.”

“It’s better . . . you’re away.” My mom gives us a brief, shaky smile, and I feel for her just then. She’s a fifty-year-old woman in teenager-like clothes. She’s had a face-lift and a boob “refill.” She has never had to work, and now this.

“What’s happening?” I ask. “You made it sound like this wouldn’t be a big deal. Everyone at school was staring at me, Mackenzie Miller made it seem like . . . like you’re some kind of criminal, and Cee won’t return my texts.”

My parents look at one another again.

“Her dad is testifying, that’s all,” my dad says. “She’s probably just concerned.”

“Testifying how?” I ask.

“Against us,” my mom says, and her words ring in my head and stay there: against us. Against us. We’re not on the same side, after all.

“Look,” my

dad says, and leans forward, as if we’re all in on something together. “The attorneys are confident, but the DA needs to make a statement and it could get uncomfortable. I can take it, but you guys shouldn’t have to, okay? Skip and Nicole are really looking forward to having you.”

Nicole is my mom’s younger sister, and all I know is they have some kind of ongoing feud, which is why this is so confusing.

“We don’t even know them,” I say. “Why can’t we stay with friends?”

“You don’t have any,” Jay says.

I’m about to throw a dig back, but his statement settles within me, finding its home. Cee is my friend, I want to say, but this sounds babyish, and right now it doesn’t seem like an option anyway.

“We should get a ruling by the end of your break. Perfect timing, and we’ll take it from there,” my mom says. She looks lost, as if she’s delivering a memorized speech that sounded good in her head but isn’t working out loud. She looks back at Sammy, then to us. “I want you to be able to have fun,” she says. “That may mean . . . you know, leaving here, and maybe . . . not telling anyone who you are.”

I’m hoping my dad will be mirroring my disbelief and disgust, but he’s not. He’s looking down at the floor.

“Nicole and Skip are going to say that you’re their niece and nephew, but from Skip’s side of the family—just in case anyone makes the connection or knows . . . the history.”

“Are you serious? That’s ridiculous.” I stand up and look down at her. “Why would we do that?”

“You’re Skip’s brother’s kids coming for a visit. You’re the Towns,” my dad says.

Jay laughs. “It’s not like we’re felons or something.”

“Just, please,” my mom yells, and Jay and I quickly lose our grins. “This is big news. There are a lot of angry people out there, and I want you to be safe.”

“Safe?” I ask.

“Not safe, but . . . I don’t want anyone judging you.” She looks down. “Alienating you. You just said everyone at school was staring.”