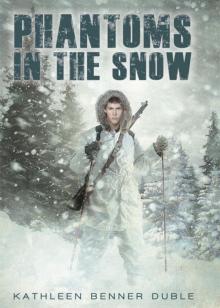

Phantoms in the Snow

Kathleen Benner Duble

KATHLEEN BENNER DUBLE

PHANTOMS IN THE SNOW

SCHOLASTIC PRESS/NEW YORK

FOR MY VERY OWN SPECIAL HERO,

BOTH IN WORLD WAR II

AND ALWAYS IN MY HEART:

MY UNCLE, LEONARD PALMER.

AND IN GRATITUDE TO THE MEN

OF THE TENTH MOUNTAIN DIVISION,

WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO PETER BINZEN,

MOUNT RIGA’S PHANTOM.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

REFERENCES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

Noah Garrett sat on the kitchen chair and listened to the rhythmic ticking of the hall clock echoing through the nearly empty rooms of his house and to the two lowered voices coming from behind the hastily shut door, the minister’s gentle and quiet, his neighbor’s shrill and determined.

Through the window, Noah could see the grass in the fields moving back and forth, the sight so familiar that his heart ached with each gust of wintry February wind. And in the distance, he could see the headstones, two of them, tall and forbidding in the midst of the rising grass. CELESTE GARRETT, LOVING WIFE, DEVOTED MOTHER, JANUARY 12, 1944, on one; MITCHELL GARRETT, LOVING HUSBAND, DEVOTED FATHER, JANUARY 17, 1944, on the other.

Noah sat rigid with worry on that kitchen chair and listened to those voices and the clock and the wind coming in through the cracks of his house. And he waited for his future to be decided.

CHAPTER TWO

The door to the train compartment was thrown open, and two boys in uniform, one short, the other tall, came tumbling in, laughing and poking each other.

After hours on the train riding alone, Noah was startled by their sudden appearance. The boys pulled up short, almost knocking into each other. The rhythm of the train made them sway as if they were deliberately rocking back and forth on their toes.

“Well, well,” said one boy. “What have we here?”

“A new recruit, it looks like,” the other boy said. “Say, kid, you coming to Denver to learn how to fly? Did you just join up to fight?”

Noah shook his head as the two boys flopped down on the seat across from him.

Fighting again, Noah thought, always fighting and the war. The war against Germany, Italy, and Japan had taken a firm hold on the country ever since the bombing of the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Everyone had rushed off to sign up and fight. Now, two years later, the battle seemed to have stalled. In Russia, the city of Leningrad was under siege, and America was losing more boys in the Pacific every day. Still, in spite of the bad news, Americans continued to sign up in droves to go and fight.

The taller of the two boys reached into his jacket and pulled out a flask. He took a swig and handed it to his buddy, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Where you headed, then?” the short one asked, taking a drink.

“Camp Hale,” Noah answered.

The two boys grinned at each other and burst into laughter.

“Now, why would you go and join a military skiing division?” the tall one asked. “You should have been smarter. You should have joined up with the Air Corps like us, been a pilot. It’s going to be us pilots, you know, who are going to whip those Germans and Japanese and win this war. That skiing division of yours won’t be of any use at all.”

“It’s not my skiing division,” Noah said. “I didn’t join. I’m only fifteen. I’m being sent there.”

“Sent to Camp Hale?” the tall one hooted. “Who would send a kid to Camp Hale?”

A minister and a neighbor, Noah thought, that’s who’d send a kid to Camp Hale; a minister and a neighbor who didn’t know what else to do with him. His parents were gone. His grandparents were dead, too. They said there was no other choice.

He thought of his mother and father — both pacifists. He remembered their talks with him about the war, how killing at any price was wrong. He imagined his mother’s horrified face if she knew he was being sent to a military camp. He imagined his father’s anguish.

He looked at the two boys across from him. Were they scared knowing that soon they would be sent to fight far from home? Had they even thought about dying or, like a lot of other boys who had signed up, did they see it all as one big adventure? Noah would never have signed up. Like his parents, Noah believed that war was not the answer to anything.

“You’re awful big for fifteen,” the short one said.

The soldier’s statement was nothing new. Everybody said the same thing to him. His father had been proud of Noah’s height. “We raise ’em big here in Texas,” his father had said, laughing. His father had always had a loud, booming laugh, one that had embarrassed Noah sometimes. Now Noah would have given anything to hear that laugh again.

“You staying for a while at Camp Hale?” the short one continued.

“Depends, I guess,” Noah said, looking out the train’s window.

“On what?” the tall one asked.

“On what my uncle and I decide once I get there,” Noah answered.

“Your uncle’s a Phantom?” the short one asked.

“Huh?” Noah said, turning from the window to face them, caught by the sudden strange word.

“Phantoms,” the tall one said. “That’s what we call them, the soldiers that ski. You can’t even see them when they’re in the mountains. They disappear like ghosts. They can ski and hike faster than normal people. It’s spooky.”

“Not that that will help us win the war.” The short one laughed. “I mean, we’re fighting those Germans in the sands of Africa for God’s sake. What are they going to do? Ski across the desert?”

“So,” the tall one persisted, “is your uncle a Phantom or not?”

Noah gazed at the older boys across from him, their uniforms starched and pressed perfectly, their shoes gleaming with polish. He thought of his uncle, the man he had never heard of until his parents died, the man he had never met. Noah felt a wave of loneliness wash over him.

“Yeah,” Noah said slowly, “I guess he is a Phantom.”

CHAPTER THREE

The two soldiers finally slumped off to sleep. Noah fidgeted on the uncomfortable wooden seat of the train and stared out the window, watching the landscape turn from flat and brown to rocky, high, and white. He thought about what lay ahead of him.

Would he ever get over losing his parents? Or would he feel this sense of loneliness forever? His whole life had been his mother, his father, and the farm.

And the future that now lay before him only increased his sense of loss. Who was this man he was being sent to? What would he be like? Why hadn’t his parents ever mentioned him?

And then there was the war issue. Even when his father had first taken him hunting, Noah had balked at shooting anything. “My gentle giant,” Mama had called him when he had returned that first day with nothing to show after having been gone for hours. Noah had liked hearing himself described that way. And though he had eventually learned to hunt with his father, he never relished the trips.

He looked at the boys asleep across the aisle from him. Wouldn’t German or Japanese boys look like that if he were sitting next to them? Wouldn’t their heads droop the same way as they slept? Wouldn’t their snores be soft and even, too? Noah could no more imagine shooting the boys across from him than he could imagine that they would shoot him back. How could they? Why would they? Why would anyone want to? It just didn’t make sense.

Looking out the window of the train at that vast expanse of white, he felt his feelings mirrored in the countryside that flew by him. It was cold and bleak.

Three hours later, the train pulled into the station at Denver. The two soldiers rose groggily from their seats, their caps askew on their heads, their pants slightly wrinkled.

“Good luck, kid,” the tall one said. “You’re going to need it with that bunch at Camp Hale.”

“Aw, don’t scare him like that,” the short one said, punching the tall one lightly on the arm. “He’ll be okay.”

He turned back to Noah. “Besides, I doubt they’ll let a fifteen-year-old stay. You’re too young yet to be on an army base. So don’t worry about it. In no time at all, you’ll probably be back home. Then when you turn sixteen, you can join up with a division that’s really going to do something. You can join us pilots!”

The short one smiled, and the tall one saluted as he straightened his cap. Noah watched the boys leave the compartment, and the train was off again.

The soldier’s statement surprised Noah. He hadn’t considered the fact that they may not let him stay at Camp Hale. But he couldn’t go back home. There was nothing there for him. Their house was for sale, the proceeds intended to pay off their farming debts. He would have to find a way to make the army let him stay, or he would have to come up with a plan to live by himself, a way to make it on his own.

Stay at Camp Hale or live alone. One or the other — those were the alternatives. An orphanage was not an option. This decided, Noah leaned his head back against the seat and fell asleep.

“Last stop! Camp Hale!” The conductor’s voice rang out as he made his way through the train, banging on each of the compartment doors.

Noah rose slowly to his feet, stretching out his muscles after the train ride from Denver. He pulled his duffel bag down from the shelf above him and threw it over his shoulder. He walked down the corridor to the door of the train.

“Off you go, then,” the conductor said, swinging the door open for him.

A rush of cold air and a foot of snow greeted Noah. He took three steps down, pulling his lightweight jacket tight around him.

Sprawled in front of him were hundreds of identical buildings. Row upon row stretched as far as he could see, whitewashed and dreary looking, a smoky fog curling just above the rooftops. And beyond the barracks rose the mountains, jagged and unyielding and yet strangely majestic. Noah had never seen so much snow or mountains like these, nor had he ever felt such cold.

A high, shrill whistle sounded, and the train began to pull away. Noah stood and watched it gather speed. A gust of wind blew through the train station.

The train rounded a bend, growing smaller and smaller. Noah suddenly felt horribly homesick.

He turned back to the barracks and the white mountains behind them. Snow swirled like dandelion fluff around him. No one was in sight.

He heard a creaking noise and turned to look. A wooden sign swung back and forth in the wind. WELCOME TO CAMP HELL, it said.

CHAPTER FOUR

Noah waited for his uncle. The snow picked up, until it was a wall of white, the flakes melting into dark spots on Noah’s pants and coat.

No one came, and the cold and wet soon penetrated Noah’s flimsy coat. He decided to walk into the camp by himself. He took several steps forward and then suddenly felt sick to his stomach. His head began to ache, and it was all he could do not to fall to his knees.

In front of him, in the middle of the swirling snow, a shape began to take form. It was white from head to toe, no face, no eyes, nothing. A ghost, Noah thought, too ill to feel fear.

Light-headedness swept over him, and Noah sank to the ground. The last thing he felt was the snow against his cheek.

He woke to the sound of laughter and the smell of coffee. He tried to sit up, but his head was pounding fiercely. He fell back against the bed he was lying on and moaned slightly.

Someone came and hovered above him. Noah focused on a man, a man who was deeply tanned and very tall with large bony hands and eyes with heavy wrinkles around them. His uncle?

“You okay, son?” he asked.

Noah tried to nod, then stopped. “My head hurts.”

The man smiled. “Yeah, it happens to a lot of new ones here. It’s the altitude, gives them headaches, makes them faint or dizzy. Don’t worry. You’ll get used to it.”

Noah wasn’t so sure. He couldn’t imagine anyone getting used to a drum being played in his head.

The man drew up a chair. “My name’s Harold Skeetman. Around here, they call me Skeeter. Can you tell me what you’re doing here? We weren’t due any new recruits for a while.”

“My name’s Noah Garrett,” Noah said, holding on to his head. It even hurt to talk. “Do you know my uncle? James Shelley?”

A cautious look crossed Skeeter’s face. “Yeah, I know him. Is he expecting you?”

Noah nodded. “I think so. My minister was supposed to write him that I was coming.”

Skeeter looked Noah up and down, his eyes carefully assessing him. “How old are you, Noah?”

Noah paused. He remembered the soldiers on the train and the fact that at least for the time being, until he could figure out a way to live alone, he had to find a way of staying here.

“I’m sixteen,” Noah answered. He was surprised at how easily the lie tripped off his tongue. He hoped his parents, if they were watching him now, would forgive him this small untruth. He would be sixteen soon enough.

“You visiting?” Skeeter asked.

“No,” Noah said and then paused. “My parents died so I was sent here. I’ve never met my uncle before.”

“Ah,” Skeeter breathed.

Noah looked quickly at Skeeter, but there was no pity there, just sadness and an odd look of understanding.

“My parents are dead, too,” Skeeter explained.

Noah nodded.

“Well,” Skeeter said finally, “why don’t you try and sit up? I’ll take you to your uncle, and we’ll straighten this all out.”

Skeeter helped Noah to his feet. Noah’s head pounded even harder. He felt like a complete weakling. Even his legs were shaking.

Skeeter handed him a wool coat, thick and warm. “You’ll need this. That jacket you brought won’t do you much good until early summer.”

Noah slipped the coat over his arm, picked up his duffel bag, and followed Skeeter into a room filled with tables. Boys, a little older than he was, sat in the room, laughing and drinking coffee. Their cheeks were bright with color and heavy with stubble.

On the walls were life-size pictures of Hitler and Hirohito, their faces marked by pinpricks from darts that h

ad been thrown their way.

As they walked by one of the tables, Noah heard someone say, “Yeah, the wind was so strong on that island that at night we tied our tent ropes to the wheels of our jeeps just to keep them down.”

Other boys, listening, nodded.

“So anyway,” the boy continued, waving his hands about as if he were a king holding court, “one morning, some soldier from another division gets up and forgets about those tents. And he gets in his jeep and drives off, pulling Wiley here” — he pointed to another boy sitting next to him with pale skin and a shock of red hair — “and his tent to the ground. So there was Wiley wiggling around inside like a worm and being dragged across the camp.”

The boys at the table burst out laughing. Noah couldn’t help it. In spite of his aching head, he laughed, too.

“Oh, you think that’s a good story,” the boy with the red hair retorted, putting his arm around the one who had told the tale. “Let me tell you one on Roger here.”

Skeeter pulled open a door and motioned Noah out. They stepped into the cold. The camp was strangely silent, blanketed with the newly fallen snow. Skeeter didn’t even pause but took off at a fast pace. Noah hurried to keep up with him, throwing on the heavy wool coat as he stumbled along. His feet sunk into the light powdery snow, and the thin air made the going difficult.

“Mr. Skeetman,” Noah called out, breathing heavily, “at the train station, when I was standing there, I thought I saw something, something all white.” He wasn’t about to add “something that looked like a ghost.”

Skeeter’s chuckle drifted back to Noah on the crisp air. “It’s Skeeter, son, just Skeeter, and that something was me. Our uniforms are all white. It keeps us invisible in the snow so we can escape or attack our enemy unseen.”

Noah thought about the pilots he had met on the train and their derogatory comments about the worthlessness of these skiing soldiers. He wondered if these boys had heard some of that kind of talk. Noah knew he would hate for people to think of him as completely useless. Did it bother these soldiers?