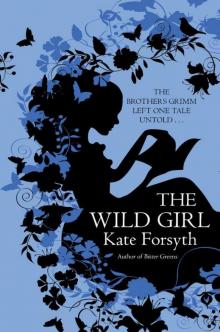

The Wild Girl

Kate Forsyth

THE WILD GIRL

Kate Forsyth

For my darling husband, Greg,

the Amen of my Universe

‘Every fairy tale had a bloody lining. Every one had teeth and claws.’

– Alice Hoffman

FOREWORD

The fairy tales collected and rewritten by the Grimm brothers in the early part of the nineteenth century have spread far and wide in the past two hundred years, inspiring many novels, poems, operas, ballets, films, cartoons and advertisements.

Most people imagine the brothers as elderly men in medieval costume, travelling around the countryside asking for tales from old women bent over their spinning wheels, or wizened shepherds tending their flocks. The truth is that they were young men in their twenties, living at the same time as Jane Austen and Lord Byron.

It was a time of war and tyranny and terror. Napoléon Bonaparte was seeking to rule as much of the world as he could, and the small German kingdom in which the brothers lived was one of the first to fall. Poverty-stricken, and filled with nationalistic zeal, Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm – the elder brothers of a family of six – decided to collect and save the old tales of princesses and goose girls, lucky fools and unlucky princes, poisonous apples and dangerous rose-briars, hungry witches and murderous sausages that had once been told and retold in houses both small and grand all over the land.

The Grimms were too poor to travel far from home; besides, the countryside was wracked by repeated waves of fighting as the great powers struggled back and forth over the German landscape. Luckily, Jakob and Wilhelm were to find a rich source of storytelling among the young women of their acquaintance. One of them, Dortchen Wild, grew up right next door.

This is her story.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Prologue: Briar Hedge

Part One: Into the Dark Forest

LANTERN IN THE NIGHT

OLD MARIE

THE WILD ONE

A RAIN OF DEATH

A BITTER BLOW

RED SUN OF AUSTERLITZ

BRAVELY GREEN

THE BLUE FLOWER

HOLLY THORNS

Part Two: Weaving Nettles

GREEN SAUCE

OLD TALES

THE THIRTEENTH DOOR

THE MERRY KIN

MIRROR, MIRROR

BROKEN AXLE

MIDSUMMER’S MORNING

OAK MOSS

A STROKE OF LUCK

Part Three: The Forbidden Chamber

SPANISH LACE

UPRISING

FIREWORKS

WINTER MELANCHOLY

MAY DAY

SPINDLE

COMMON RUE

THE STORY WIFE

GIRL IN ASHES

Part Four: The Singing Bone

THIEF IN THE NIGHT

THE OPIUM CHEST

MAIDEN WITH NO HANDS

CLAMOUR OF BELLS

HELTER-SKELTER

THE COMET

FIRE AND FROST

THE SINGING BONE

MIDSUMMER SWOON

Part Five: The Skin of Wild Beasts

THE MARCH AGAINST RUSSIA

ALMIGHTY FATHER

PRAYING

ALL-KINDS-OF-FUR

THE COLDEST WINTER

THE YELLOW DRESS

NO USE WEEPING

RED BLOOD, WHITE FEATHERS

THE BEAST WITHIN

Part Six: The Red Boundary Stone

THE FALL OF WESTPHALIA

THE RUSSIAN INVASION

UNKIND

RETURN OF THE PRINCE

IN THE VALLEY OF THE SHADOW

HEAD OF THE HOUSEHOLD

GO TO HELL

HER MASTER

AN EARLY GRAVE

Part Seven: The Singing, Springing Lark

IMPOSSIBLE DREAMS

A SHEATH OF ICE

GOLDEN LEAF

BLINDMAN’S BLUFF

WRITTEN IN THE STARS

A HIGH REGARD

DOG IN A MANGER

BY THE LIGHT OF THE NEW MOON

CORNFLOWERS

Epilogue: The True Bride

Afterword

Sources of the Grimms’ Stories

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By Kate Forsyth

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Briar Hedge

CASSEL

The Electorate of Hessen-Cassel, December 1814

And the maiden changed herself into a rose which stood in the midst of a briar hedge, and her sweetheart Roland into a fiddler. It was not long before the witch came striding up towards them, and said: ‘Dear musician, may I pluck that flower for myself?’ ‘Oh, yes,’ he replied, ‘I will play to you while you do it.’ As the witch crept into the hedge and reached to pluck the flower, he began to play, and she was forced to dance. The faster he played, the faster she danced, and the thorns tore her clothes from her body, pricking and wounding her till she bled. As he did not stop playing, the witch had to dance till she lay dead on the ground.

From ‘Sweetheart Roland’, a tale told by Dortchen Wild to Wilhelm Grimm on 19th January 1812

‘Wild by name and wild by nature,’ Dortchen’s father used to say of her. He did not mean it as a compliment. He thought her headstrong, and so he set himself to tame her.

The day Dortchen Wild’s father died, she went to the forest, winter-bare and snow-frosted, so no one could see her dancing with joy. She went to the place where she had last been truly happy, the grove of old linden trees in the palace garden. Tearing off her black bonnet, she flung it into the tangled twigs, and drew off her gloves, shoving them in her coat pocket. Holding out her bare hands, embracing the cold winter wind, Dortchen spun alone among the linden trees, her black skirts swaying.

Snow lay thick upon the ground. The lake’s edges were slurred with ice. The only colour was the red rosehips in the briar hedge, and the golden windows of the palace. Violin music lilted into the air, and shadows twirled past the glass panes.

It was Christmas Day. All through Cassel, people were dancing and feasting. Dortchen remembered the Christmas balls Jérôme Bonaparte had held during his seven-year reign as king. A thousand guests had waltzed till dawn, their faces hidden behind masks. Wilhelm I, the Kurfürst of Hessen, had won back his throne from the French only a little over a year ago. He would not celebrate Christmas so extravagantly. Soon the lights would be doused and the music would fade away, and he and his court would go sensibly to bed, to save on the cost of lamp oil.

Dortchen must dance while she could.

She lifted her black skirts and twirled in the snow. He’s dead, she sang to herself. I’m free!

Three ravens flew through the darkening forest, wings ebony-black against the white snow. Their haunting call chilled her. She came to a standstill, surprised to find she was shaking with tears as much as with cold. She caught hold of a thorny branch to steady herself. Snow showered over her.

I will never be free …

Dortchen was so cold that she felt as if she were made of ice. Looking down, she realised she had cut herself on the rose thorns. Blood dripped into the snow. She sucked the cut, and the taste of her blood filled her mouth, metallic as biting a bullet.

The sun was sinking away behind the palace, and the violin music came to an end. Dortchen did not want to go home, but it was not safe in the forest at night. She picked up her bonnet and began trudging back home, to the rambling old house above her father’s apothecary shop, where his corpse lay in his bedroom, swollen and stinking, waiting for her to wash it and lay it out.

The town was full of revellers. It was the first Christmas since Napol�

�on had been defeated and banished. Carol-singers in long red gowns stood on street corners, singing harmonies. A chestnut-seller was selling paper cones of hot chestnuts to the crowd clustered about his little fire, while potmen sold mugs of hot cider and mulled wine. All the young women were dressed in British red and Russian green and Prussian blue, trimmed with military frogging and golden braid – a vast change from the previous year, when all had worn the high-waisted white favoured by the Empress Joséphine. Dortchen’s severe black dress and bonnet made her look like a hooded crow among a vast flock of gaudy parrots.

At last she came to the Marktgasse, lit up with dancing light from a huge bonfire. Not one building matched another, crowded together all higgledy-piggledy around the cobblestoned square with its old pump and drinking trough outside the inn.

Only the apothecary’s shop was dark and shuttered, with no welcoming light above its door. Dortchen made her way through crowds buying sugar-roasted almonds, gingerbread hearts, wooden toys and small gilded angels at the market stalls. She slipped into the alley that ran down the side of the shop to its garden, locked away behind high walls.

‘Dortchen,’ a low voice called from the shadowy doorway opposite the garden gate.

She turned, hands clasped painfully tight together.

A tall, lean figure in black stepped out of the doorway. The light from the square flickered over the strong, spare bones of his face, making hollows of his eyes and cheeks.

‘I’ve been waiting for you,’ Wilhelm said. ‘No one knew where you had gone.’

‘I went to the forest,’ she answered.

Wilhelm nodded. ‘I thought you would.’ He put his arms about her, drawing her close.

For a moment Dortchen resisted, but she was so cold and tired that she could not withstand the comfort of his touch. She rested her cheek on his chest and heard the thunder of his heart.

A ragged breath escaped her. ‘He’s dead,’ she said. ‘I can hardly believe it.’

‘I know, I heard the news. I’m sorry.’

‘I’m not.’

He did not answer. She knew she had grieved him. The death of Wilhelm’s father had been the first great sorrow of his life; he and his brother Jakob had worked hard ever since to be all their father would have wanted. It was different for Dortchen, though. She had not loved her father.

‘You’re free now,’ he said, his voice so low it could scarcely be heard over the laughter and singing of the crowd in the square.

Dortchen had to look away. ‘It doesn’t change anything. There’s nothing left for me, not a single thaler.’

‘Wouldn’t Rudolf—’

Dortchen made a restless movement at the mention of her brother. ‘There’s not much left for him either. All the wars … and then my father’s illness … Well, Rudolf’s close to ruin as it is.’

There was a long silence. In the space between them were all the words Wilhelm could not say. I am too poor to take a wife … I earn so little at my job at the library … I cannot ask Jakob to feed another mouth when he has to support all six of us …

The failure of their fairy tale collection was a disappointment to him, Dortchen knew. Wilhelm had worked so hard, pinning all his hopes to it. If only it had been better received … If only it had sold more …

‘I’m so sorry.’ He bent his head and kissed her.

Dortchen drew away and shook her head. ‘I can’t … We mustn’t …’ He gave a murmur deep in his throat and tried to kiss her again. She wrenched herself out of his arms. ‘Wilhelm, I can’t … It hurts too much.’

He caught her and drew her back, and she did not have the strength to resist him. Once again his mouth found hers, and she succumbed to the old magic. Desire quickened between them. Her arms were about his neck, their cold lips opening hungrily to each other. His hand slid down to find the curve of her waist, and she drew herself up against him. His breath caught. He turned and pressed her against the stone wall, his hands trying to find the shape of her within her heavy black gown.

Dortchen let herself forget the dark years that gaped between them, pretending that she was once more just a girl, madly in love with the boy next door.

The church bells rang out, marking the hour. She remembered she was frozen to the bone, and that her father’s dead body lay on the far side of the wall.

‘It’s no use,’ she whispered, pulling herself out of Wilhelm’s arms. It felt like she was tearing away living flesh. ‘Please, Wilhelm … don’t make it harder.’

He held her steady, bending his head so his forehead met hers. ‘Our time will come.’

She shook her head. ‘It’s too late.’

‘Don’t say that. I cannot bear it, Dortchen. It’ll never be too late. I love you – you know that I do. Someday, somehow, we’ll be together.’

She sighed and tried once more to draw away. He gripped her forearms and said, in a low, intense voice, ‘I’ve been reading Novalis. Do you remember? He said the most beautiful thing about love. It’s given me new faith, Dortchen.’

‘What did he say?’ she asked, wanting to believe, if only for a minute.

‘Love works magic,’ Wilhelm said. ‘It is the final purpose of the world story, the “Amen” of the universe.’

She caught her breath in a sob and reached up to kiss him. For a long moment, the world stilled around them. Dortchen thought of nothing but the feel of his arms about her, his mouth on hers. But then the bonfire in the square flared up, sending the shadows racing away, and a great drunken cheer sounded out. Dortchen stepped back. ‘I must go.’

‘Must you?’ He tried to hold her still so he could kiss her again.

She turned her face away. ‘Wilhelm, we can’t do this any more,’ she said to the stones in the wall. ‘I … I need to make some kind of life for myself.’

He took a deep, unhappy breath. ‘What will you do?’

‘I’ll keep house for Rudolf, I suppose. And help my sisters. There’s always work for Aunty Dortchen.’ Her voice was bitter. At twenty-one years of age, she was an old maid, all her hopes of love and romance turned to ashes.

‘There must be a way. If the fairy tales would sell just a few more copies …’ His voice died away. They both knew that he would need to sell many thousands more before they could ever dream of being together.

‘One day people will recognise how wonderful the stories are,’ she said.

He took her hand and bent before her, pressing his mouth into her palm. She drew away from him, turning to the gate in the wall. She was shivering so hard she could scarcely lift the latch. She glanced back and saw him watching her, a tall, still shadow among shadows.

Happy endings are only for fairy tales, Dortchen thought, stepping through to her father’s walled garden. She raised her hand to dash away her tears. These days, there’s no use in wishing.

PART ONE

Into the Dark Forest

CASSEL

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, 1805–1806

So they walked for a long time and finally came to the middle of the great forest. There the father made a big fire and the mother says: ‘Sleep for a while, children, we want to go into the forest and look for wood, wait till we come back.’ The children sat down next to the fire, and each one ate its little piece of bread. They wait a long time until night falls, but the parents don’t come back.

From ‘Hänsel and Gretel’, a tale thought to have been told by Dortchen Wild to Wilhelm Grimm before 1810

LANTERN IN THE NIGHT

October 1805

Dortchen Wild fell in love with Wilhelm Grimm the first time she saw him.

She was only twelve years old, but love has never been something that can be constrained by age. It happened in the way of old tales, in an instant, changing everything forever. It was a fork in the path, the turn of a key, the kindling of a lantern.

That afternoon, Dortchen had gone with her friend Lotte to visit Lotte’s aunt, Henriette Zimmer, who was a lady-in-waiting to the Prin

cess Wilhelmine. They had been accompanied by Lotte’s mother, Frau Grimm, and three of her brothers, Karl, Ferdinand and Ludwig. It was a long walk back to the Marktgasse from the vast green park of the palace, but no one suggested hiring a carriage. The Grimms were poor, and Dortchen certainly had no money in her purse. It was both scary and wonderful to walk through the forest at twilight, imagining wolves and witches and bears and other wild beasts lurking in the shadows.

‘Look at Herkules,’ Lotte said. ‘He’s all lit up by the sun.’

Dortchen turned and walked backward, staring back up at the palace, square and grand on its low hill, with six heavy columns holding up a great stone pediment. On the crest of the mountain behind was an octagonal building of turreted stone, surmounted by a pyramid on which stood the immense statue of Herkules, symbol of the Kurfürst’s power. As the sun slid down behind the western horizon, Herkules sank back into shadow. Light drained away from the sky.

‘Hurry up, girls!’ Frau Grimm called. ‘It’ll be dark soon.’

Supper, Dortchen thought. She turned forward again and quickened her steps. ‘I mustn’t be late or Father will be angry.’

‘He won’t mind once he knows you’ve been with us, surely,’ Lotte said.

Dortchen did not like to say that her father did not approve of the Grimm family. There were far too many boys for his comfort, and, besides, they were as poor as church mice. Herr Wild had six girls to settle comfortably.

The shadowy forest gave way to parkland, then the long, straight road ran between wide plots of gardens, each confined behind stone walls, the gateposts carved with the initials of the owners’ long-dead ancestors. They approached Dortchen’s family’s garden plot, where she had been meant to spend all afternoon, weeding and hoeing. She ran in and caught up her basket and gardening gloves, then hurried to catch up with Lotte, who turned to wait for her, one hand clamped to her bonnet.