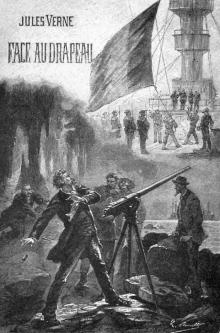

Face au drapeau. English

Jules Verne

Produced by Norm Wolcott and PG Distributed Proofreaders

Facing the Flag by Jules Verne

[Redactor's Note: _Facing the Flag_ {number V044 in the T&M listing ofVerne's works} is an anonymous translation of _Face au drapeau_ (1896)first published in the U.S. by F. Tennyson Neely in 1897, and later(circa 1903) republished from the same plates by Hurst and F.M. Lupton(Federal Book Co.). This is a different translation from the onepublished by Sampson & Low in England entitled _For the Flag_ (1897)translated by Mrs. Cashel Hoey.]

------------------------------------------------------------------------

FACING THE FLAG

BY

J U L E S V E R N E

AUTHOR OF "AROUND THE WORLD IN EIGHTY DAYS"; "TWENTYTHOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA"; "FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON," ETC.

New York

THE F. M. LUPTON PUBLISHING COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

------------------------------------------------------------------------

1897

------------------------------------------------------------------------

CONTENTS

CHAP

I. Healthful House

II. Count d'Artigas

III. Kidnapped

IV. The Schooner "Ebba"

V. Where am I.--(Notes by Simon Hart, the Engineer.)

VI. On Deck

VII. Two Days at Sea

VIII. Back Cup

IX. Inside Back Cup

X. Ker Karraje

XI. Five Weeks in Back Cup

XII. Engineer Serko's Advice

XIII. God Be with It

XIV. Battle Between the "Sword" and the Tug

XV. Expectation

XVI. Only a few more Hours

XVII. One against Five

XVIII. On Board the "Tonnant"

------------------------------------------------------------------------

FACING THE FLAG.

CHAPTER I.

HEALTHFUL HOUSE.

The _carte de visite_ received that day, June 15, 189-, by thedirector of the establishment of Healthful House was a very neat one,and simply bore, without escutcheon or coronet, the name:

COUNT D'ARTIGAS.

Below this name, in a corner of the card, the following address waswritten in lead pencil:

"On board the schooner _Ebba_, anchored off New-Berne, Pamlico Sound."

The capital of North Carolina--one of the forty-four states of theUnion at this epoch--is the rather important town of Raleigh, which isabout one hundred and fifty miles in the interior of the province. Itis owing to its central position that this city has become the seatof the State legislature, for there are others that equal andeven surpass it in industrial and commercial importance, such asWilmington, Charlotte, Fayetteville, Edenton, Washington, Salisbury,Tarborough, Halifax, and New-Berne. The latter town is situated onestuary of the Neuse River, which empties itself into Pamlico Sound, asort of vast maritime lake protected by a natural dyke formed by theisles and islets of the Carolina coast.

The director of Healthful House could never have imagined why the cardshould have been sent to him, had it not been accompanied by anote from the Count d'Artigas soliciting permission to visit theestablishment. The personage in question hoped that the director wouldgrant his request, and announced that he would present himself in theafternoon, accompanied by Captain Spade, commander of the schooner_Ebba_.

This desire to penetrate to the interior of the celebrated sanitarium,then in great request by the wealthy invalids of the United States,was natural enough on the part of a foreigner. Others who did not bearsuch a high-sounding name as the Count d'Artigas had visited it, andhad been unstinting in their compliments to the director. The lattertherefore hastened to accord the authorization demanded, and addedthat he would be honored to open the doors of the establishment to theCount d'Artigas.

Healthful House, which contained a select _personnel_, and was assuredof the co-operation of the most celebrated doctors in the country, wasa private enterprise. Independent of hospitals and almshouses, butsubjected to the surveillance of the State, it comprised all theconditions of comfort and salubrity essential to establishments ofthis description designed to receive an opulent _clientele_.

It would have been difficult to find a more agreeable situation thanthat of Healthful House. On the landward slope of a hill extended apark of two hundred acres planted with the magnificent vegetation thatgrows so luxuriantly in that part of North America, which is equal inlatitude to the Canary and Madeira Islands. At the furthermost limitof the park lay the wide estuary of the Neuse, swept by the coolbreezes of Pamlico Sound and by the winds that blew from the oceanbeyond the narrow _lido_ of the coast.

Healthful House, where rich invalids were cared for under suchexcellent hygienic conditions, was more generally reserved for thetreatment of chronic complaints; but the management did not decline toadmit patients affected by mental troubles, when the latter were notof an incurable nature.

It thus happened--a circumstance that was bound to attract a good dealof attention to Healthful House, and which perhaps was the motivefor the visit of the Count d'Artigas--that a person of world-widenotoriety had for eighteen months been under special observationthere.

This person was a Frenchman named Thomas Roch, forty-five years ofage. He was, beyond question, suffering from some mental malady, butexpert alienists admitted that he had not entirely lost the use ofhis reasoning faculties. It was only too evident that he had lost allnotion of things as far as the ordinary acts of life were concerned;but in regard to subjects demanding the exercise of his genius, hissanity was unimpaired and unassailable--a fact which demonstrates howtrue is the _dictum_ that genius and madness are often closelyallied! Otherwise his condition manifested itself by complete lossof memory;--the impossibility of concentrating his attention uponanything, lack of judgment, delirium and incoherence. He no longereven possessed the natural animal instinct of self-preservation, andhad to be watched like an infant whom one never permits out of one'ssight. Therefore a warder was detailed to keep close watch over himby day and by night in Pavilion No. 17, at the end of Healthful HousePark, which had been specially set apart for him.

Ordinary insanity, when it is not incurable, can only be cured bymoral means. Medicine and therapeutics are powerless, and theirinefficacy has long been recognized by specialists. Were these moralmeans applicable to the case of Thomas Roch? One may be permittedto doubt it, even amid the tranquil and salubrious surroundings ofHealthful House. As a matter of fact the very symptoms of uneasiness,changes of temper, irritability, queer traits of character,melancholy, apathy, and a repugnance for serious occupations weredistinctly apparent; no treatment seemed capable of curing or evenalleviating these symptoms. This was patent to all his medicalattendants.

It has been justly remarked that madness is an excess of subjectivity;that is to say, a state in which the mind accords too much to mentallabor and not enough to outward impressions. In the case of ThomasRoch this indifference was practically absolute. He lived but withinhimself, so to speak, a prey to a fixed idea which had brought him tothe condition in which we find him. Could any circumstance occurto counteract it--to "exteriorize" him, as it were? The thing wasimprobable, but it was not impossible.

It is now necessary to explain how this Frenchman came to quit France,what motive attracted him to the United States, why the Federalgovernment had judged it prudent and necessary to intern him in thissanitarium, where every utt

erance that unconsciously escaped himduring his crises were noted and recorded with the minutest care.

Eighteen months previously the Secretary of the Navy at Washington,had received a demand for an audience in regard to a communicationthat Thomas Roch desired to make to him.

As soon as he glanced at the name, the secretary perfectly understoodthe nature of the communication and the terms which would accompanyit, and an immediate audience was unhesitatingly accorded.

Thomas Roch's notoriety was indeed such that, out of solicitude forthe interests confided to his keeping, and which he was bound tosafeguard, he could not hesitate to receive the petitioner and listento the proposals which the latter desired personally to submit to him.

Thomas Roch was an inventor--an inventor of genius. Several importantdiscoveries had brought him prominently to the notice of theworld. Thanks to him, problems that had previously remained purelytheoretical had received practical application. He occupied aconspicuous place in the front rank of the army of science. It will beseen how worry, deceptions, mortification, and the outrages with whichhe was overwhelmed by the cynical wits of the press combined to drivehim to that degree of madness which necessitated his internment inHealthful House.

His latest invention in war-engines bore the name of Roch'sFulgurator. This apparatus possessed, if he was to be believed, suchsuperiority over all others, that the State which acquired it wouldbecome absolute master of earth and ocean.

The deplorable difficulties inventors encounter in connection withtheir inventions are only too well known, especially when theyendeavor to get them adopted by governmental commissions. Several ofthe most celebrated examples are still fresh in everybody's memory.It is useless to insist upon this point, because there are sometimescircumstances underlying affairs of this kind upon which it isdifficult to obtain any light. In regard to Thomas Roch, however,it is only fair to say that, as in the case of the majority of hispredecessors, his pretensions were excessive. He placed such anexorbitant price upon his new engine that it was practicablyimpossible to treat with him.

This was due to the fact--and it should not be lost sight of--that inrespect of previous inventions which had been most fruitful in result,he had been imposed upon with the greatest audacity. Being unableto obtain therefrom the profits which he had a right to expect, histemper had become soured. He became suspicious, would give up nothingwithout knowing just what he was doing, impose conditions thatwere perhaps unacceptable, wanted his mere assertions accepted assufficient guarantee, and in any case asked for such a large sum ofmoney on account before condescending to furnish the test of practicalexperiment that his overtures could not be entertained.

In the first place he had offered the fulgurator to France, and madeknown the nature of it to the commission appointed to pass upon hisproposition. The fulgurator was a sort of auto-propulsive engine,of peculiar construction, charged with an explosive composed of newsubstances and which only produced its effect under the action of adeflagrator that was also new.

When this engine, no matter in what way it was launched, exploded, noton striking the object aimed at, but several hundred yards from it,its action upon the atmospheric strata was so terrific that anyconstruction, warship or floating battery, within a zone of twelvethousand square yards, would be blown to atoms. This was the principleof the shell launched by the Zalinski pneumatic gun with whichexperiments had already been made at that epoch, but its results weremultiplied at least a hundred-fold.

If, therefore, Thomas Roch's invention possessed this power, itassured the offensive and defensive superiority of his native country.But might not the inventor be exaggerating, notwithstanding that thetests of other engines he had conceived had proved incontestably thatthey were all he had claimed them to be? This, experiment could aloneshow, and it was precisely here where the rub came in. Roch wouldnot agree to experiment until the millions at which he valued hisfulgurator had first been paid to him.

It is certain that a sort of disequilibrium had then occurred in hismental faculties. It was felt that he was developing a condition ofmind that would gradually lead to definite madness. No governmentcould possibly condescend to treat with him under the conditions heimposed.

The French commission was compelled to break off all negotiations withhim, and the newspapers, even those of the Radical Opposition, had toadmit that it was difficult to follow up the affair.

In view of the excess of subjectivity which was unceasingly augmentingin the profoundly disturbed mind of Thomas Roch, no one will besurprised at the fact that the cord of patriotism gradually relaxeduntil it ceased to vibrate. For the honor of human nature be it saidthat Thomas Roch was by this time irresponsible for his actions. Hepreserved his whole consciousness only in so far as subjects bearingdirectly upon his invention were concerned. In this particular he hadlost nothing of his mental power. But in all that related to the mostordinary details of existence his moral decrepitude increased dailyand deprived him of complete responsibility for his acts.

Thomas Roch's invention having been refused by the commission, stepsought to have been taken to prevent him from offering it elsewhere.Nothing of the kind was done, and there a great mistake was made.

The inevitable was bound to happen, and it did. Under a growingirritability the sentiment of patriotism, which is the very essence ofthe citizen--who before belonging to himself belongs to his country--became extinct in the soul of the disappointed inventor. His thoughtsturned towards other nations. He crossed the frontier, and forgettingthe ineffaceable past, offered the fulgurator to Germany.

There, as soon as his exorbitant demands were made known, thegovernment refused to receive his communication. Besides, it sohappened that the military authorities were just then absorbed by theconstruction of a new ballistic engine, and imagined they could affordto ignore that of the French inventor.

As the result of this second rebuff Roch's anger became coupled withhatred--an instinctive hatred of humanity--especially after his_pourparlers_ with the British Admiralty came to naught. The Englishbeing practical people, did not at first repulse Thomas Roch. Theysounded him and tried to get round him; but Roch would listen tonothing. His secret was worth millions, and these millions he wouldhave, or they would not have his secret. The Admiralty at lastdeclined to have anything more to do with him.

It was in these conditions, when his intellectual trouble was growingdaily worse, that he made a last effort by approaching the AmericanGovernment. That was about eighteen months before this story opens.

The Americans, being even more practical than the English, did notattempt to bargain for Roch's fulgurator, to which, in view of theFrench chemist's reputation, they attached exceptional importance.They rightly esteemed him a man of genius, and took the measuresjustified by his condition, prepared to indemnify him equitably later.

As Thomas Roch gave only too visible proofs of mental alienation,the Administration, in the very interest of his invention, judged itprudent to sequestrate him.

As is already known, he was not confined in a lunatic asylum, but wasconveyed to Healthful House, which offered every guarantee for theproper treatment of his malady. Yet, though the most careful attentionhad been devoted to him, no improvement had manifested itself.

Thomas Roch, let it be again remarked--this point cannot be too ofteninsisted upon--incapable though he was of comprehending and performingthe ordinary acts and duties of life, recovered all his powers whenthe field of his discoveries was touched upon. He became animated, andspoke with the assurance of a man who knows whereof he is descanting,and an authority that carried conviction with it. In the heat of hiseloquence he would describe the marvellous qualities of his fulguratorand the truly extraordinary effects it caused. As to the nature of theexplosive and of the deflagrator, the elements of which the latter wascomposed, their manufacture, and the way in which they were employed,he preserved complete silence, and all attempts to worm the secret outof him remained ineffectual. Once or twice, during the height of theparox

ysms to which he was occasionally subject, there had been reasonto believe that his secret would escape him, and every precaution hadbeen taken to note his slightest utterance. But Thomas Roch hadeach time disappointed his watchers. If he no longer preserved thesentiment of self-preservation, he at least knew how to preserve thesecret of his discovery.

Pavilion No. 17 was situated in the middle of a garden that wassurrounded by hedges, and here Roch was accustomed to take exerciseunder the surveillance of his guardian. This guardian lived in thesame pavilion, slept in the same room with him, and kept constantwatch upon him, never leaving him for an hour. He hung uponthe lightest words uttered by the patient in the course of hishallucinations, which generally occurred in the intermediary statebetween sleeping and waking--watched and listened while he dreamed.

This guardian was known as Gaydon. Shortly after the sequestration ofThomas Roch, having learned that an attendant speaking French fluentlywas wanted, he had applied at Healthful House for the place, and hadbeen engaged to look after the new inmate.

In reality the alleged Gaydon was a French engineer named Simon Hart,who for several years past had been connected with a manufactory ofchemical products in New Jersey. Simon Hart was forty years of age.His high forehead was furrowed with the wrinkle that denoted thethinker, and his resolute bearing denoted energy combined withtenacity. Extremely well versed in the various questions relating tothe perfecting of modern armaments, Hart knew everything that had beeninvented in the shape of explosives, of which there were over elevenhundred at that time, and was fully able to appreciate such a manas Thomas Roch. He firmly believed in the power of the latter'sfulgurator, and had no doubt whatever that the inventor had conceivedan engine that was capable of revolutionizing the condition of bothoffensive and defensive warfare on land and sea. He was aware that thedemon of insanity had respected the man of science, and that in Roch'spartially diseased brain the flame of genius still burned brightly.Then it occurred to him that if, during Roch's crises, his secret wasrevealed, this invention of a Frenchman would be seized upon by someother country to the detriment of France. Impelled by a spirit ofpatriotism, he made up his mind to offer himself as Thomas Roch'sguardian, by passing himself off as an American thoroughly conversantwith the French language, in order that if the inventor did at anytime disclose his secret, France alone should benefit thereby. Onpretext of returning to Europe, he resigned his position at the NewJersey manufactory, and changed his name so that none should know whathad become of him.

Thus it came to pass that Simon Hart, alias Gaydon, had been anattendant at Healthful House for fifteen months. It required no littlecourage on the part of a man of his position and education to performthe menial and exacting duties of an insane man's attendant; but, ashas been before remarked, he was actuated by a spirit of the purestand noblest patriotism. The idea of depriving Roch of the legitimatebenefits due to the inventor, if he succeeded in learning his secret,never for an instant entered his mind.

He had kept the patient under the closest possible observation forfifteen months yet had not been able to learn anything from him,or worm out of him a single reply to his questions that was of theslightest value. But he had become more convinced than ever of theimportance of Thomas Roch's discovery, and was extremely apprehensivelest the partial madness of the inventor should become general, orlest he should die during one of his paroxysms and carry his secretwith him to the grave.

This was Simon Hart's position, and this the mission to which he hadwholly devoted himself in the interest of his native country.

However, notwithstanding his deceptions and troubles, Thomas Roch'sphysical health, thanks to his vigorous constitution, was notparticularly affected. A man of medium height, with a large head,high, wide forehead, strongly-cut features, iron-gray hair andmoustache, eyes generally haggard, but which became piercing andimperious when illuminated by his dominant idea, thin lips closelycompressed, as though to prevent the escape of a word that couldbetray his secret--such was the inventor confined in one ofthe pavilions of Healthful House, probably unconscious of hissequestration, and confided to the surveillance of Simon Hart theengineer, become Gaydon the warder.