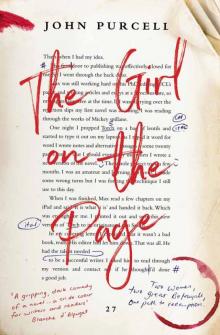

The Girl On the Page

John Purcell

Dedication

For Tamsin

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1: Wednesday, 27 July 2016

Chapter 2: Past Engagement

Chapter 3: #AHundredWays

Chapter 4: A Good Hard Edit

Chapter 5: Retirement

Chapter 6: American Psycho

Chapter 7: Google ‘Helen Owen News’

Chapter 8: Leather Notebook

Chapter 9: Intermission

Chapter 10: Brighton 1979

Chapter 11: Seelenlos

Chapter 12: Women Writers’ Guild Awards

Chapter 13: The Lodger

Chapter 14: A Work Thing

Chapter 15: Bleach, Lemon and Death

Chapter 16: They Shouldn’t Be Much Longer

Chapter 17: Don’t Fuck the Boss

Chapter 18: A Little Charity

Chapter 19: Whatever Is Necessary

Chapter 20: Amy’s Decision

Chapter 21: Did You Say a Million?

Chapter 22: I’d Forgotten His Ways

Chapter 23: Publish This

Chapter 24: Because You Owe Me

Chapter 25: So You Think I Should Publish It?

Chapter 26: I Think They Cleared Your Desk

Chapter 27: You Wouldn’t Say That

Chapter 28: This Is My Inheritance

Chapter 29: Sorry, but It’s Too Hot in Here for Clothes

Chapter 30: Too Good for Them

Chapter 31: You Know Me Better Than Anyone

Chapter 32: He Couldn’t Tell

Chapter 33: Not Like Hers

Chapter 34: We Tried Our Best

Chapter 35: Tuesday, 13 September 2016

Chapter 36: Nothing to Be Ashamed of

Chapter 37: Max’s Notes I

Chapter 38: It’s Perfectly Fine as It Is

Chapter 39: All the Light Had Gone Out

Chapter 40: The Truth Is Just Fucking Fine

Chapter 41: Daniel on the Road

Chapter 42: Max’s Notes II

Chapter 43: Sometimes It’s Hard to Let Go

Chapter 44: One Hundred Per Cent behind the Book

Chapter 45: Max’s Notes III

Chapter 46: Malcolm Taylor Is Here

Chapter 47: Liam Messages Amy

Chapter 48: A Bridge Too Far

Chapter 49: Amy Messages Max

Chapter 50: How Are the Boys?

Chapter 51: In the Newspaper

Chapter 52: Try Writing about It

Chapter 53: Nothing

Chapter 54: Who Were You to Him?

Chapter 55: Just One More Drink?

Chapter 56: You’ve Been Sleeping

Chapter 57: Retail Therapy

Chapter 58: Have You Written Your Speech?

Chapter 59: Booker Night

Chapter 60: More Than Any Book

Chapter 61: Don’t Do This

Chapter 62: The Notebook

Chapter 63: Knowing What We Know

Chapter 64: But Who Would Do Such a Thing?

Chapter 65: Phone Message

Chapter 66: Max’s Article

Chapter 67: All Too Human

Epilogue

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

Prologue

‘Amy, what are you doing?’

I was sitting naked on his loo with his laptop. It was 4 am and I’d only met him the night before. The question was reasonable.

He’d remembered my name, which was cute.

‘The edits on the new Archer,’ I answered, without looking up from the screen. ‘He’s not mine, but a friend called in a favour.’

I saved my work to the cloud, trying to remember if he had been a guest at the book launch, in which case he’d know what I’d meant by ‘the new Archer’, or a member of the bar staff. One quick glance at him confirmed it for me. He was standing there completely naked – tats, six-pack, stubble, enormous package – definitely bar staff.

‘What? How’d you log in?’

‘I’m on as a guest. Don’t worry,’ I said, logging out and closing the lid, ‘I haven’t been going through your porn collection. I mean I would have been, but I couldn’t get in. Go back to bed. I’ll let myself out.’

‘Are you going?’ he asked, stepping forward and taking my hand in his.

I handed him the laptop and looked up. Nope, I couldn’t for the life of me remember tattoo boy’s name.

‘If I stay, can I take a photo of your cock for my blog?’

His cock stirred and he smiled.

‘Check your phone. You took a million already.’

And so that is how it is with me. I’m an insomniac. I drink way too much. I take naughty pics. I like to fuck strangers. And I’m a workaholic who will edit books on any computer I can break into.

Chapter 1

Wednesday, 27 July 2016

‘They’re here,’ said Helen, who had been watching from the window of her West London terrace. Her husband, Malcolm, was standing in the doorway to the sitting room waiting for this news. He strode down the corridor and pulled open the front door.

Parked outside the house was a black Citroën estate car. A man in his late forties with sparse sandy hair was standing by the open driver’s door, arms raised in a luxurious stretch. He began to yawn and then saw Malcolm walking towards the front gate.

‘Hi, Dad,’ he said, mid yawn, adding, ‘Hi, Mum,’ when he saw Helen at the door.

‘Good trip, Daniel?’ asked Malcolm.

‘Fair,’ he answered. He opened the back door, reached in, took out his tan blazer and put it on. ‘The weather’s better here. It’s been miserable in Edinburgh. This is glorious.’ He glanced briefly at the blue sky. When his gaze returned to Malcolm, he added, ‘You’ve had the house painted. Looks like all the others now. I didn’t recognise it. Lucky I remembered the number.’

Malcolm nodded and was about to say something when the passenger door opened and a woman in her late twenties emerged. She gave Malcolm and Helen a tight smile and then opened the back door and helped two little boys out. The boys stood on the pavement in matching jeans and ruby red jumpers and stared up at Malcolm. They looked like they had been woken from a nap.

Helen opened the gate and crouched down. ‘Hello, boys!’

The boys stared at Helen, expressionless. After a moment, the younger of the two decided it was best to bury his face in the heavy material of his mother’s charcoal skirt.

‘Hello, Geraldine,’ said Malcolm as he watched his wife try to coax the remaining boy into a smile.

Geraldine stepped forward awkwardly, the little boy still clinging to her, and gave Malcolm a quick kiss on the cheek. ‘The boys and I have been asleep.’

‘It’s a long drive,’ said Helen, admitting defeat with the boys and standing up. She was struck by how much Daniel had aged. He was almost twenty years older than Geraldine and it was more evident than ever. Geraldine, always attractive, had become a dark beauty. Her face was thinner and more defined. And though shy in this moment, her eyes showed that she had matured and was more herself than ever.

‘We did it in seven hours,’ said Daniel. ‘And we stopped for lunch. The boys can watch DVDs in the back. They were great, weren’t they?’ Geraldine nodded. ‘What’s the best movie ever, Charlie?’ he asked touching the boy’s shoulder.

‘Frozen,’ came the muffled reply from within the folds of his mother’s skirt.

‘Geraldine, go in with the boys. I’ll help Daniel with the bags.’

‘No rush, Dad, we’ll get them later. I’d kill for a cup of tea.’

Malco

lm ushered the visitors into the front room, while Helen went off to make tea. Entering the room, he pointed out the train set Helen had set up on the floor for the boys. The boys clung to their parents tenaciously.

‘That was once Daddy’s train, Samuel,’ said Daniel, leading the elder of the two by the hand, ‘from when I was a little boy like you.’

Both Geraldine and Malcolm watched in silence, still standing by the door, as Daniel got down on his haunches and showed Samuel how it worked. Charlie left his mother’s skirt and went over to see, too.

When Helen returned with a full tray of tea things, Malcolm and Geraldine still hadn’t thought to sit down. It became obvious to both that they had been behaving awkwardly. Malcolm hastened off to the window, passing his son and grandsons on his way, and proceeded to check the weather. Geraldine took the tray from Helen and placed it on the coffee table, allowing Helen to return to the kitchen to see to the now boiling kettle.

Once the tea was poured, and everyone was settled, the adults watched the two boys playing with the train. Daniel had remained on the floor but now turned to the coffee table to stir his tea and take a few tentative sips.

‘I’m sorry we couldn’t get down for Christmas. Geraldine’s parents always put on a big family Christmas and the look of disappointment on their faces when I floated the idea of spending Christmas in London was too much. I know your views on religious ceremonies and thought you both wouldn’t mind too much,’ said Daniel, his eyes travelling from Geraldine, alone on the sofa to his right, to his mother and father, seated on his left.

Helen almost spoke. She almost said that it didn’t matter. Her head and shoulders lifted almost imperceptibly, in order to speak. But it had mattered. And consciousness of this fact kept her silent.

Malcolm, thinking he was about to hear the words he knew Helen must say, remained silent, too. So real was his premonition of her speech, he’d thought he’d heard it. But only for the shortest of moments.

‘We didn’t handle it well,’ admitted Geraldine. ‘To make arrangements with you and then to break them at the last minute wasn’t . . .’ Her words died on her lips.

Daniel gave his wife a reassuring smile. He was glad she hadn’t said anything more. He knew his parents were waiting for an apology and Geraldine had almost given them one. But he knew better than anyone how much she had been dreading that Christmas visit to London, almost as much as she had been dreading this current visit. If anyone deserved an apology it was Geraldine. His parents had never made any effort to get to know her.

‘It was difficult,’ said Malcolm.

‘I don’t want to speak about it,’ said Helen, instead of the words that had come to mind. These had made her feel uncomfortable. They were so ordinary. We were both hurt, she might have said. But she recoiled from the idea. They weren’t people who said such things. Or felt such things. She was facing behaviour that was so distressingly ordinary that only ordinary speech and emotion applied. But she wouldn’t stoop. Daniel and Geraldine were singularly selfish and unrepentant. To proceed, that fact would have to be agreed upon by all present. And that wasn’t going to happen.

‘What can we speak about then?’ asked Daniel. Helen knew the tone of this question well. It never took long before the facade of the good son crumbled.

‘I read your article on the library closures in Scotland,’ said Malcolm.

‘We both did,’ said Helen.

‘I don’t want to discuss my writing with either of you. I was compelled to write. In my work I see first-hand the deterioration of literacy standards. But writing, I have no ambitions in that direction.’

Geraldine, alert to her husband’s tone, spoke before either Helen or Malcolm could. ‘Daniel said you’ll be celebrating your fiftieth wedding anniversary in October.’

‘Yes, we will,’ answered Malcolm, unhelpfully.

‘And your work, Geraldine, will you be returning now the boys are older?’ asked Helen.

‘I never really stopped. Clients still come to the house. The boys are very good. They know when I’m working. Sometimes they join in. I’m now thinking about running yoga classes designed specifically for children.’

Neither Helen nor Malcolm could find a reply to this. Helen wondered why she had asked. She looked down at the boys and felt none of the joy she had expected to feel. The excitement generated by the anticipation of the visit was smothered by the reality.

Daniel was adept at reading the direction of his mother’s thoughts. He was not so adept at comprehending their cause. He didn’t need to look at his wife to know that she’d be hurt by his parents’ failure to show sustained interest in her. The visit was going just as he had expected it to.

As the silence lengthened it grew uncomfortable.

‘No one would ask for you two as parents,’ Daniel said quietly, looking at the surface of the coffee table. He glanced up at Malcolm and added, ‘Some might, I suppose, not knowing you. Thinking they know you. But they don’t know you.’

Malcolm sighed and sank back into the sofa while observing Helen closely. The expression on his wife’s face pained him. With a hint of weariness, he said, ‘The same old Daniel. Desperate to be a real boy.’

‘Why shouldn’t I want that? I know the difference now,’ Daniel continued. ‘I’ve seen what I’ve missed. My boys won’t miss out. I won’t refuse my sons the privilege of normality.’

Malcolm repeated the phrase to himself softly, ‘Privilege of normality.’

‘They’ll miss out,’ said Helen, sharply, ‘just as you have. Not on the things you’re referring to. Whatever your concept of normality is. But that doesn’t matter. It really doesn’t. Not these days. Perhaps not ever.’ She had failed to convey her meaning. She blamed her audience. She didn’t know how to talk to Daniel when he was being so wilfully obtuse. She lifted the plate of biscuits and held them out to the boys. Each took a chocolate one.

‘I didn’t want exceptional parents. I don’t want exceptional parents. I want a normal mum and dad.’

‘So you’ve said. An unvarying insistence since you were about fifteen. We were unequal to your tenacity. Normality, any kind, was impossible in those circumstances. Every single thing we did had to be abnormal in your eyes. And then as soon as you could, you left. Moved to Edinburgh. We haven’t seen you. Any of you. You would have spent more time with your dentist than us in the last twenty-five years. And now you expect this to be normal?’ asked Malcolm, with a grim smile. He had been hopeful of some change after reading Daniel’s article. The article had mentioned both Helen and Malcolm and spoke of the importance of having been brought up surrounded by books and conversation. How he had been a regular visitor to Brixton Library as a child and the impact this had had on him. But now it was obvious their shared history had been important to his argument and nothing more.

‘You know what to expect when you visit us,’ said Helen. ‘I don’t know why we come as such a shock time and time again. Isn’t it time to accept us as we are?’

‘No. And I don’t think I will ever be able to convince you why I think this. But if you had been with us at Geraldine’s family’s Christmas, you would have seen what I mean. We all had such a marvellous time. There were twenty-five of us in total. A real Christmas, with a tree, tinsel, carols, terrible jumpers, presents and children squealing with delight.’

‘It was lovely. I wish you’d been there,’ said Geraldine, without conviction.

‘Really lovely,’ continued Daniel. ‘I couldn’t bring Geraldine and the boys here. They’d miss out on all that. It wouldn’t be fair.’

‘What did you two do for Christmas?’ asked Geraldine.

‘Salman Rushdie joined us for dinner,’ answered Malcolm, drily.

‘That’s what I’m talking about! Who does that?’ asked Daniel, standing.

‘I’ll help you get the bags,’ said Malcolm, standing as well.

‘We’re not staying,’ said Daniel.

Both Malcolm and Helen stared in disbelief. D

aniel and his family had just driven seven hours and had been planning to stay a week.

‘We’ve booked a hotel,’ chimed in Geraldine. ‘We’ve plans to see some old friends while we’re here.’

‘We’ve prepared the flat below,’ said Helen. ‘Separate entrance. You can come and go as you please.’

‘You’ll be entirely independent,’ said Malcolm. ‘Kitchenette, bathroom, two double beds. You’ll have everything you need.’

‘No, we won’t,’ said Daniel, shaking his head slowly. ‘No, we won’t.’

He bent down and lifted Samuel. The child was clutching a train engine. He rested him on his hip.

‘Don’t go. This is madness,’ said Helen. ‘How do you think any of this will get better?’

‘We need to spend some time together,’ added Malcolm with feeling.

Daniel looked around the room. He had seen the house before, just after they’d bought it and before they’d moved in. They’d spent money on it since then, he could see. Painted and decorated. While they’d talked he had noted the paintings, the ornaments on the shelves, the books, the two sofas, the sleek television, the coffee table. All of it appeared to be new.

‘You lived in Brixton in the same squalid flat for fifty years – my entire life – and now this . . .’ He carried the boy to the door. He looked directly at Helen, adding, ‘You might have sold out earlier.’

Geraldine followed him to the door with Charlie, who wasn’t very pleased to leave the train set. He started to resist and then cried. Helen picked up one of the engines and gave it to him. He wouldn’t look at her, but took it all the same.

‘Let them go,’ said Malcolm, when he saw that Helen was following them out.

‘I don’t want them to go,’ she said, visibly shaken.

‘You think I do?’

They went to the window and watched the young family get into the car, buckle up and drive off.

‘They had no intention of staying,’ said Malcolm, placing his hand on Helen’s shoulder.

‘If we’d been different . . .’ she began, then sighed, knowing where their self-recriminations always led, and moved away from Malcolm and the window.

Malcolm followed.

Helen started clearing away the tea things.