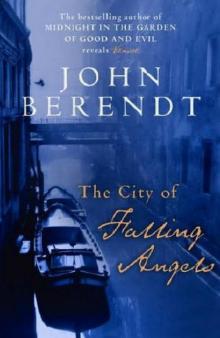

The City of Falling Angels

John Berendt

Table of Contents

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

{1} - AN EVENING IN VENICE

{2} - DUST & ASHES

{3} - AT WATER LEVEL

{4} - SLEEPWALKING

{5} - SLOW BURN

{6} - THE RAT MAN OF TREVISO

{7} - GLASS WARFARE

{8} - EXPATRIATES: THE FIRST FAMILY

{9} - THE LAST CANTO

{10} - FOR A COUPLE OF BUCKS

{11} - OPERA BUFFA

{12} - BEWARE OF FALLING ANGELS

{13} - THE MAN WHO LOVED OTHERS

{14} - THE INFERNO REVISITED

{15} - OPEN HOUSE

GLOSSARY

PEOPLE, ORGANIZATIONS, AND COMPANIES

NAMES OF BUILDINGS AND PLACES

Acknowledgements

Praise for The City of Falling Angels by John Berendt

Voted one of the Best Books of the Year by Publishers Weekly,

USA Today, Amazon, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post,

Chicago Tribune, Detroit Free-Press, Rocky Mountain News,

The Baltimore Sun, The Salt Lake Tribune

“Surely as he arrived in Venice, Berendt was . . . looking for something to write about, something that would not be a letdown for him or his readers after the incredible success of Midnight. Not to keep you in suspense: He found it. . . . [T]he story of the Fenice fire and its aftermath is exceptionally interesting, the cast of characters is suitably various and flamboyant, and Berendt’s prose, now as then, is precise, evocative and witty.”—Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post

“Once again, Mr. Berendt makes erudite, inquisitive, nicely skeptical company as he leads the reader through the shadows of what was heretofore better known as a tourist attraction. . . . [H]e delivers an urbane, beautifully fashioned book with much exotic charm.”

—Janet Maslin, The New York Times

“An intriguing tour of mysterious Venice and its most fascinating residents. . . . Venice may be sinking, but in Berendt’s capable hands, the city has never seemed more colorful, perplexing and alluring . . . an engaging journey in which the author navigates Venice’s shadowy politics, its tangled bureaucracy and its elegant high-society nightlife with a discerning, sanguine touch.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“John Berendt once again captures the marvelous seamy side of midnight society.”—Vanity Fair

“In Berendt’s hands, the reader comes to know the city as an almost organic thing—an ancient creature . . . bearing generations of Venetians.”

—The Buffalo News

“Berendt has given us something uniquely different. . . . Thanks to [his] splendid city-portrait, even those of us far from Venice can marvel.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“I cannot stop haunting travel Web sites in search of cheap fares to Italy. Angels is that good. . . . Berendt proves himself to be a masterful writer. . . . [He] crafts a lean and elegant narrative. . . . Berendt is that rare writer devoured by millions.”—USA Today

“This is a book to carry you away . . . a haunting book.”

—The Observer

“Fascinating . . . [T]here’s been a lot of talk about the art of the nonfiction ‘novel,’ a literary form credited to Truman [Capote]. These days we have Mr. Berendt. . . . This tale of the glamorous, fetid, mythic, schizophrenic slowly sinking city on the Adriatic Sea—along with its evasive denizens—makes for a hypnotic read. Berendt is the best at what he does.”—Liz Smith, New York Post

“If Berendt seems unusually calm for all the expectations placed on The City of Falling Angels, it is perhaps because he has written a book better than his first: a kaleidoscopic, vibrant, deeply human portrait of Venice, Italy, and, more specifically, the people who live there—poets, arsonists, poison makers, glass blowers, questionable ex-pats, performance artists. It is a detective story, a book of puzzles, a comic tale of sorrow, a poignant narrative of absurdity. . . . The book, like its author, crackles with life, color, and passion.”

—Pages

“As refreshing as a chilly Bellini on a humid afternoon, The City of Falling Angels captures Venice’s inhabitants and intrigues through a series of sharp, well-defined sketches and explores the amusing stink of its bureaucratic corruption, high society skirmishes and daring artistic feats. Berendt immerses us deeply in the city’s culture and we emerge sputtering and thrilled.”

—The Miami Herald

“Both by happenstance and design, Berendt finds himself in an atmosphere rich with personalities, and he takes full advantage of them in crafting an elegant, and elegiac, narrative.”

—St. Petersburg Times (Florida)

“After Byron’s lascivious Venice, Henry James’s sepulchral Venice, and Thomas Mann’s sickly sweet Venice, is there room for yet another exhumation of the city’s corpse? Mr. Berendt proves that there is ... [in this] fast-paced, entertaining narrative that serves up course after course of human folly.”—The New York Sun

“How lucky we are to have John Berendt. . . . Venice is the gorgeous subject of [his] latest tour de force of social observation. . . . Lovers of Midnight have waited twelve years for Berendt to offer another book, and I’m glad to say the wait has been worth it. . . . Berendt reports and writes so beautifully, so seamlessly, that a reader might think the work was easy.”—Detroit Free Press

“Berendt is at his best when he writes about the internecine grudges and eccentricities of Venice’s movers and shakers.”

—Orlando Sentinel

“Berendt’s storytelling skills sparkle.”—The Gazette (Montreal)

“In documenting the Fenice fire and rebuilding, Berendt adds a necessary chapter to the literary oeuvre about Venice. No doubt both Venice lovers and Berendt fans will devour this book.”

—Edmonton Journal (Alberta)

“Berendt has worked hard to tie together not merely all the strands of a complicated story but also the various aspects of Venice . . . rarely seen by the tourists who swarm through the beautiful old city. His prose . . . is a pleasure to read.”

—Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Book World

“This is journalism at its most accomplished; it is creative nonfiction as enveloping and heart embracing as good fiction.”—Booklist

“Once again Berendt proves himself a stylist with an uncanny talent for holding reader interest.”—Star-Tribune (Minneapolis)

“Richly atmospheric, entertaining and informative.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“Berendt delivers yet another book so readable the pages almost seem to turn themselves.”—Rocky Mountain News

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Berendt has been a columnist for Esquire, the editor of New York magazine, and the author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which was a finalist for the 1995 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction. He lives in New York.

To request Penguin Readers Guides by mail (while supplies last), please call (800) 778-6425 or e-mail [email protected]. To access Penguin Readers Guides online, visit our Web site at www.penguin.com

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Cam

berwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2005

Published in Penguin Books 2006

Copyright © High Water, Incorporated, 2005

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following selections:

“Fragment (1966)” from The Cantos of Ezra Pound by Ezra Pound.

Copyright © 1934, 1937, 1940, 1948, 1956, 1959, 1962, 1963, 1966, 1968 by Ezra Pound.

.

“Ciao Cara” from Ezra Pound, Father and Teacher: Discretions by Mary de Rachewiltz.

Copyright © 1971, 1975 by Mary de Rachewiltz.

.

Excerpt from the diary of Daniel Sargent Curtis. .

“Dear [Sir]” letter from Olga Rudge to lawyer, April 24, 1988.

.

“Dearest Mother” letter from Mary de Rachewiltz to her mother, Olga Rudge, February 24, 1988.

.

eISBN : 978-1-436-28735-7

1. Venice (Italy)—Description and travel. 2. Venice (Italy)—Social life and customs.

I. Title

DG674.2.B47 2005

945’.31—dc22 2005047661

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only

authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy

of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For Harold Hayes and Clay Felker

BEWARE OF FALLING ANGELS

—Sign posted outside the Santa Maria della Salute Church in Venice in the early 1970s, before restoration of its marble ornaments

AUTHOR’S NOTE

THIS IS A WORK OF NONFICTION. All the people in it are real and are identified by their real names. There are no composite characters. For the reader’s convenience, a partial list of people and places appears at the end of the book, along with a glossary of Italian words used frequently in the text.

PROLOGUE:

THE VENICE EFFECT

EVERYONE IN VENICE IS ACTING,” Count Girolamo Marcello told me. “Everyone plays a role, and the role changes. The key to understanding Venetians is rhythm—the rhythm of the lagoon, the rhythm of the water, the tides, the waves. . . .”

I had been walking along Calle della Mandola when I ran into Count Marcello. He was a member of an old Venetian family and was considered an authority on the history, the social structure, and especially the subtleties of Venice. As we were both headed in the same direction, I joined him.

“The rhythm in Venice is like breathing,” he said. “High water, high pressure: tense. Low water, low pressure: relaxed. Venetians are not at all attuned to the rhythm of the wheel. That is for other places, places with motor vehicles. Ours is the rhythm of the Adriatic. The rhythm of the sea. In Venice the rhythm flows along with the tide, and the tide changes every six hours.”

Count Marcello inhaled deeply. “How do you see a bridge?”

“Pardon me?” I asked. “A bridge?”

“Do you see a bridge as an obstacle—as just another set of steps to climb to get from one side of a canal to the other? We Venetians do not see bridges as obstacles. To us bridges are transitions. We go over them very slowly. They are part of the rhythm. They are the links between two parts of a theater, like changes in scenery, or like the progression from Act One of a play to Act Two. Our role changes as we go over bridges. We cross from one reality . . . to another reality. From one street . . . to another street. From one setting . . . to another setting.”

We were approaching a bridge crossing over Rio di San Luca into Campo Manin.

“A trompe l’oeil painting,” Count Marcello went on, “is a painting that is so lifelike it doesn’t look like a painting at all. It looks like real life, but of course it is not. It is reality once removed. What, then, is a trompe l’oeil painting when it is reflected in a mirror? Reality twice removed?

“Sunlight on a canal is reflected up through a window onto the ceiling, then from the ceiling onto a vase, and from the vase onto a glass, or a silver bowl. Which is the real sunlight? Which is the real reflection?

“What is true? What is not true? The answer is not so simple, because the truth can change. I can change. You can change. That is the Venice effect.”

We descended from the bridge into Campo Manin. Other than having come from the deep shade of Calle della Mandola into the bright sunlight of the open square, I felt unchanged. My role, whatever it was, remained the same as it had been before the bridge. I did not, of course, admit this to Count Marcello. But I looked at him to see if he would acknowledge having undergone any change himself.

He breathed deeply as we walked into Campo Manin. Then, with an air of finality, he said, “Venetians never tell the truth. We mean precisely the opposite of what we say.”

{1}

AN EVENING IN VENICE

THE AIR STILL SMELLED OF CHARCOAL when I arrived in Venice three days after the fire. As it happened, the timing of my visit was purely coincidental. I had made plans, months before, to come to Venice for a few weeks in the off-season in order to enjoy the city without the crush of other tourists.

“If there had been a wind Monday night,” the water-taxi driver told me as we came across the lagoon from the airport, “there wouldn’t be a Venice to come to.”

“How did it happen?” I asked.

The taxi driver shrugged. “How do all these things happen?”

It was early February, in the middle of the peaceful lull that settles over Venice every year between New Year’s Day and Carnival. The tourists had gone, and in their absence the Venice they inhabited had all but closed down. Hotel lobbies and souvenir shops stood virtually empty. Gondolas lay tethered to poles and covered in blue tarpaulin. Unbought copies of the International Herald Tribune remained on newsstand racks all day, and pigeons abandoned sparse pickings in St. Mark’s Square to scavenge for crumbs in other parts of the city.

Meanwhile the other Venice, the one inhabited by Venetians, was as busy as ever—the neighborhood shops, the vegetable stands, the fish markets, the wine bars. For these few weeks, Venetians could stride through their city without having to squeeze past dense clusters of slow-moving tourists. The city breathed, its pulse quickened. Venetians had Venice all to themselves.

But the atmosphere was subdued. People spoke in hushed, dazed tones of the sort one hears when there has been a sudden death in the family. The subject was on everyone’s lips. Within days I had heard about it in such detail I felt as if I had been there myself.

IT HAPPENED ON MONDAY EVENING, January 29, 1996.

Shortly before nine o’clock, Archimede Seguso sat down at the dinner table and unfolded his napkin. Before joining him, his wife went into the living room to lower the curtains, which was her longstanding evening ritual. Signora Seguso knew very well that no one could see in through the windows, but it was her way of enfolding her family in a domestic embrace. The Segusos lived on the third floor of Ca’ Capello, a sixteenth-century house in the heart of Venice. A narrow canal wrapped around two sides of the building before flowing into the Grand Canal a short distance away.

Signor Seguso waited patiently at

the table. He was eighty-six—tall, thin, his posture still erect. A fringe of wispy white hair and flaring eyebrows gave him the look of a kindly sorcerer, full of wonder and surprise. He had an animated face and sparkling eyes that captivated everyone who met him. If you happened to be in his presence for any length of time, however, your eye would eventually be drawn to his hands.