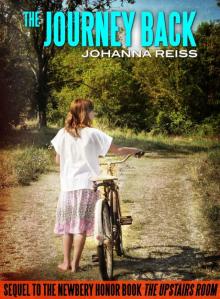

The Journey Back

Johanna Reiss

THE

JOURNEY BACK

JOHANNA REISS

To my daughters,

Julie and Kathy,

who were my guides

Contents

Part One: Usselo

1

2

3

4

Part Two: Summer

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Part Three: Fall And Winter

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Part Four: Spring

1

2

3

4

Johanna Reiss' Personal Photos

Interview With Johanna Reiss

Locations From The Book You Can Explore

About the Author

The house where Johanna Reiss and her sister hid for almost three years from the Nazis.

PART ONE

* USSELO *

*

1 *

It is not easy to find Usselo. On many maps of Holland you cannot find it at all, only on those that list every village, no matter how tiny. Not many people, however, care to know where Usselo is. Why, there is hardly anything there—fields, a café, a bakery, a school, a church and parsonage, a kind of dry-goods store in a house, and farmhouses, but only a handful of those. There’s no more than that in Usselo. Such a quiet little village, where life was orderly and pleasant for years and years and years.

Sometimes there would be a wedding, or a funeral to which every farmer went, walking two by two behind the hearse, talking in hushed and not so hushed voices.

“Quiet, he’s not buried yet.” “But what’s true’s true. He was as dumb as a pig’s ass. Take how he planted potatoes … no good … right smack next to each other … told’m so, too … wouldn’t listen. He could never have gotten as many basketfuls as he said he did. If you ask me, I’d say he was a liar.”

There were dances, too, in the café, where an accordion player pulled and pushed and pressed down on keys and buttons with fingers that were stiff from farmwork, while around him, legs waltzed and polkaed inside tight black pants and long black skirts, and lace caps slid off, showing hair that was stiff and shiny from sweet milk that had been rubbed on to make it so.

Year after year, every season, the same things happened in Usselo. In the winter pigs were slaughtered, and the farmers visited each other, sipping from glasses as they commented on the animal that was hanging from a ladder in front of them, cut open.

“She’s got a tasty border of fat on’r, not like Willem’s pig we just saw. …” “Some sausage this one will make— No, thanks, not another drop. Don’t forget, we’ve got three more calls to make today. All right, a little bit then, to wet the throat.”

And back on their bikes they’d go because soon it would be time to milk the cows.

During the rest of the year they saw each other, too, the farmers of Usselo. Outside, in the fields, behind plows and wielding sickles, on hay wagons, and as they were binding the sheaves of rye, wearing straw hats this time, against the sun; the women in white aprons with long sleeves but no gloves, their hands scratched and their nails broken. And they saw each other with baskets of seed potatoes on their arms, and turnips, and cabbage. They knew each other well. But then there were so few of them, not more than a handful.

The Oostervelds lived in Usselo, and had for over fifty years. Their farm was small. When Johan Oosterveld was a child, he went to the one-room schoolhouse, just like the few other children in Usselo. Sometimes he played soccer, as they did, but only sometimes and never for more than a short time. His father was sick; Johan was an only child, and even though the farm was small, there was a lot of work that had to be done.

“Johan, Joha-a-a-an, come home.” And his mother would give him a piece of bread on which she had sprinkled salt, so he’d be able to taste the thin layer of butter better; before she sent him to get the horse and plow. And off he would go, down the road, to where the fields were. “C’mon, horse; come, come, come.” It was not easy to make straight furrows in the soil. He was only eleven, Johan, and the plow was heavy.

His father continued to be sick for six more years. Johan no longer went to school at all, or played. He had no time.

“Too bad,” his teacher said when Johan didn’t come back. “That boy has brains, Vrouw Oosterveld. He could go far, become a teacher, like me. …” Instead it was “C’mon, horse; come, come, come” year after year after year. But I did not know any of this then. How could I? I was not even born yet.

When Johan was seventeen, his father died.

“Take it easy for a few days now,” his mother said. “Look around and find someone to marry. But, please, don’t choose a girl from the city. They don’t know what work is. Get someone with a good pair of hands, Johan, to help.”

“Leave it to me, Ma,” Johan said. “I’ll see what I can do.”

He looked around Usselo. Then in the next village, the one that was only half a mile away, he found Dientje. “Wait till you see her, Ma,” he said. “She’s got a real pair of hands on her—you won’t believe how big they are. We can both take it easy from now on. She’s a lot older than me, too. She must really know how to work. And I’ll tell you something else. We’re going to be rich. She’s got a real—what-d’you-call-it—dowry. Some bedding, and this you’ll love, Ma, five chickens and none of them scrawny. Maybe even a cow if I play my cards right. Eh?”

“My Johan,” his mother said proudly, wiping her eyes.

After the wedding the three of them lived in the little farmhouse—Johan, Dientje, and Johan’s mother—Opoe, as everyone called her, although she never did become a grandmother. And life went on. Orderly and pleasant enough, until—But not yet. There were more weddings and funerals to go to first, more plowing to do and harvesting and sausage making.

Johan and his mother still worked very hard. “It’s funny, Ma, with such hands who would’ve thought. … Dientje always wants to rest.”

While Johan, Dientje, and Opoe lived in Usselo, I was living with my family in another town, a much bigger one, Winterswijk, forty kilometers away, where my father was a cattle dealer. He used to take me with him in his car when he went to call on customers.

“De Leeuw, good to see you again,” they’d say. “That little black-and-white cow you sold us is doing well, is giving even more milk than you said she would, but the milk is watery and we feel we paid too much. Does Annie want a cookie?”

Sure. I’d take one. I did not even have to choose. They were always the same—yellow with sugar sprinkles. “Thank you,” I’d say to the farmer’s wife. I’d try not to stare at the container, which was always put back in the same place it had come from, a cabinet on the wall, behind glass. I’d wait for Father to be ready, so we could leave, drive to another farmer, to another cookie with sprinkles. I liked going with him.

I liked many things. Being home with my two sisters, Sini and Rachel, if they were nice to me. They were much older—adults almost. With Mother—only she was always sick. With Marie, our maid, who let me sit on her back as she cleaned the floors on all fours. And I liked being with other children, friends, with whom I climbed trees, ran, and laughed. Life went on for us, too, in Winterswijk, in the big house in which we lived.

*

2 *

Then the Second World War broke out in Europe. Adolf Hitler, chancellor of Germany, wanted his country to be big and powerful and glorious again, as it

had been many times in history. Many Germans agreed, and joined his Nazi party.

It was 1939 and autumn when Hitler’s army invaded Poland. “Go,” he said to his soldiers, “and don’t stop.”

In less than ten months they had occupied Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, and Holland. They even found Usselo. It was May 1940. The members of the royal House of Orange, which had been reigning over our country for hundreds of years, fled. The enemy stayed.

Our lives did not change much—not right away. Father still went out in his car; Mother was still sick; Rachel and Sini continued to work. I was in school now, in the second grade.

And in Usselo? They barely knew there was a war. Not until the farmers had trouble getting enough feed for their cattle, and the enemy demanded a cow from everyone. Hitler’s soldiers were hungry, and there were many of them.

“Goddammit, I think we’ve got a war on our hands, Ma, Dientje,” Johan said angrily. He was even surer when the enemy wanted still another cow; eggs now, too, and copper, which they turned into bullets. But apart from becoming even poorer and having begun to curse, Johan’s life had not changed: “C’mon, horse; come, come, come,” furrow after furrow.

The enemy hated many people: gypsies, Slavs, Communists, priests, and almost everyone who was not German or who dared to disagree. Above all, Hitler hated Jews, and in every country his soldiers occupied, he began to make life especially hard for them. He forbade them to work, travel, shop, go to school. He forbade them more, and more. Until—yes, now—Jews were being dragged out of their houses and off the streets and pushed into freight cars that were locked and cramped and without air.

“Go,” Hitler yelled to his soldiers. “Go, go. Don’t waste time.” The trains left on Tuesdays for Austria, Germany, and Poland, for camps that were hard to pronounce—Mauthausen, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Auschwitz. Where they were murdered, the Jews and the others who disagreed. But most of them were Jews.

The Oostervelds did not like to hear about this. “Goddammit, Dientje, Ma, what kind of people are those Germans?” But it all seemed far away. Johan had seen a Jew only once in his life. “That good-for-nothing cattle dealer Cohen from the city, who pinched our cow in the nose when I said he wasn’t offering enough money for her. She almost died.”

There was just as much work to be done in the fields and around the farm, but life was no longer the same, no longer orderly, or even a little bit pleasant.

There were no more weddings to go to. Those who did get married made nothing of it. There was not enough food to give a party. The enemy, you know. No more sausage making, either—no pigs. The enemy. … Only funerals were left, but even they were no longer the same. The farmers were afraid to say much. What if they complained about the war—it was hard not to— and someone overheard? Like Willem, who thought the Germans were wonderful—he might turn them in. The soldiers would come and take them away. … Two by two, they walked behind the hearse, the handful of farmers, with their mouths shut.

But their lives had not changed as much as ours. So much shouting at home. We were Jews. We didn’t want to end up on those trains that left on Tuesdays.

“We must hide,” Father said, “if I can find Gentile people who’ll take us in.” After a while he did find places for us. Secretly we left town, Father for a city near Rotterdam. “It will not be for long,” he said. Half the world seemed to be fighting against Hitler now, and against Germany’s partners, Italy and Japan. England was, France, Canada, Russia, the United States, other Allied countries. How long could the war last?

My sister Sini and I? We went to Usselo, to live with a family named Hannink. A few weeks later, Mother died and was hurriedly buried. Only then did Rachel leave, for a small village hours from Winterswijk. She was the last Jew from our town to do so. It was November, 1942.

*

3 *

After a few months we could no longer stay with the Hanninks. It was too dangerous, Mr. Hannink said. The Germans were suspicious of him; they thought he might be hiding Jews. “If they find you here, we’ll be murdered, too—my wife, my daughter, and myself. You must leave.”

Late one evening, when it was dark out and no one could see us, Sini and I arrived at the Oostervelds’ door. There they were, the three of them. Frightened, I looked at the man, Johan. He was big. His face was red, and he had brown hair that grew straight up. His cheeks were thin, hollow almost, as if for years the wind and rain had beaten on them and left dents.

“Hiya.” He smiled around a cigarette butt that hung from the corners of his mouth. “Two Jewish girls. I’ll be damned. Who would’ve thought it, Ma. Of all the farmers to choose from in Usselo, Mr. Hannink picked me. Ja, ja, girls, he’s an important man. I bet he thought I was brave enough to take this big risk. Because that’s what it is, a big risk. They could kill us all.” He shifted the cigarette butt to the other side of his mouth.

“Let’s see,” he went on, “that little one, Annie,must be about ten or eleven. The sister’s a lot older, I’d, say. Sure, Ma, look for yourself. About twenty, I’d guess.” He walked over to his mother and took her by the shoulders. “Ma, after all these years you’re really an Opoe. Eh? You like that?”

She did. She laughed up at him with her whole face, all her wrinkles, her toothless mouth. “Two girls at once, Johan. Nice ones, too.”

Now I could laugh. It was all right. They liked us.

“Ssht,” Dientje warned, “not so loud for God’s sake.” She looked scared. She reminded everybody of what Mr. Hannink had said. A few weeks, that was all. Then he’d take us back.

But Mr. Hannink never did. No one even mentioned it. Already we had been with the Oostervelds for months. Father had been wrong. Still the war. …

Sure, the Oostervelds were nice, very nice. But the days were long. So many hours in one day, so many days. On some, the sun was out; on others, not. Or it rained or not. We had to keep away from the window, so that no one could catch a glimpse of us and mention that the Oostervelds had strangers living upstairs. “I could swear to it. I looked up and there they were—two girls. Who can they be, I wonder? Eh?”

What if Willem heard? He’d tell the enemy. They’d come. “Wosind sie?” they’d scream, and take us away.

Clop, clop. There was a farmer going by, his wooden shoes stamping outside. He had a horse with him, too. I could hear the hooves. Which way were they going? To the left? To the right? Down the road or up, and how far? To another town? Which one? Which one?

From where I was sitting, I looked at Sini. She had not said a word for hours. I looked at the wall, the ceiling, the floor, which was covered with speckled linoleum and took no time to cross—five seconds. Someday I’d get up; I’d walk out of this room and I’d keep on walking forever, through fields and meadows and across ditches. … When they were gone, the soldiers, and it was safe.

Finally the Germans were beginning to lose, in Russia and in Africa. Maybe they’d keep on losing now. I could hear myself running down the stairs already—kla-bonk, kla-bonk—on my way home to Winterswijk.

Maybe Father could take us somewhere, to celebrate. Would we go to the little hotel by the ocean where we used to spend our vacations? Without Mother though? I swallowed. No, a brand-new place would be better. I knew of one, too. Yes, yes. Ssht, you almost made a noise. Can’t. Quiet. Willem. …

It was an island called Walcheren in the south-western part of Holland, not far from Belgium. I had seen pictures of it in a big book, colored pictures, of hedges with red and white flowers that grew around fields and gardens. Hardly any of the people wore ordinary clothes. No, they wore old-fashioned ones—black pants, long skirts. They wore a lot of golden ornaments and beads, too. It would take a whole day to get to Walcheren, but I wouldn’t mind. I’d sit close to Father, help him steer the car. “Careful, there’s a tree.” Oops.

Rachel would pack a picnic; there’d be pancakes with raisins for eyes. We’d stop by the side of the road—or, and this would even be nicer, we’d eat in

the woods, hear birds, see tiny animals. But I wouldn’t want to sit for long. I’d get up quickly to jump over the shafts of light that were coming through the trees. Here; no, there.

After a few minutes Father would want to leave. “C’mon,” he’d say, and with his mouth still full, he’d hurry back to the car. “Rachel, Sini, Annie—last chance.”

I smiled in the direction of the window. Father was a little impatient, but we hurried. We didn’t want to get there after dark, either!

There were dikes all around the island of Walcheren, high, high ones, to protect it from the North Sea. I’d climb up on one, up and up, to the top. And I’d stand sideways so that I could see everything, land as well as water. Look how the water sparkles in the sun! A boat sliding by as in a dream … and a bird, a speck of white—

“Careful, don’t fall!”

Silly Rachel. I wouldn’t. It is very windy though. My hair … I close my eyes to keep it out. Now I can even hear the water as it crashes against the bottom of the dike, far, far beneath me, swishing and splashing, never stopping. … “Look, it’s raining again,” Sini complained. “As if it isn’t already dark enough in the back of the room.”

At night it wasn’t dark. The minute the Oostervelds were finished with their work, they’d rush upstairs, pull the shades down, and turn on the light.

“That’s better, girls, right? Ja, ja, Dientje knows.” With a sigh she’d sit down, her hands folded on her stomach. Once in a while she’d bend forward and carefully touch my face. “I’m so glad you’re here, my little Annie,” she’d say, and nod.

“Sini,” Johan said, “I want you to tell me again what Winterswijk looks like so I get a good picture of it in my head.” Carefully he’d listen. “Here, Maand Dientje are always saying things I’ve heard for years. ‘Milk the cows, feed the horse, dig up the potatoes.’ Bah, I know it all by heart. This, I like. It’s giving me a new set of brains. Dientje, let’s have some more of that coffee even though it’s no good, and don’t tell me that’s because it’s a substitute. I remember how it tasted before.”