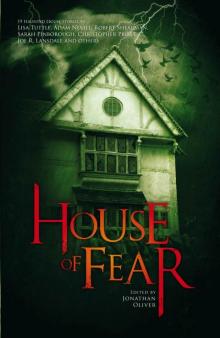

House of Fear

Joe R. Lansdale

House of Fear

Edited by Jonathan Oliver

Nineteen new stories of haunted houses and spectral encounters by:

Lisa Tuttle

Stephen Volk

Terry Lamsley

Adam L. G. Nevill

Weston Ochse

Rebecca Levene

Garry Kilworth

Chaz Brenchley

Robert Shearman

Nina Allan

Christopher Fowler

Sarah Pinborough

Paul Meloy

Christopher Priest

Jonathan Green

Nicholas Royle

Eric Brown

Tim Lebbon

Joe R. Lansdale

First published 2011 by Solaris, an imprint of Rebellion Publishing Ltd, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK

www.solarisbooks.com

ISBN (.epub): 978-1-84997-297-0

ISBN (.mobi): 978-1-84997-298-7

‘Objects in Dreams may be Closer than they Appear’

copyright © Lisa Tuttle 2011

‘Pied-à-terre’ copyright © Stephen Volk 2011

‘In the Absence of Murdock’ copyright © Terry Lamsley 2011

‘Florrie’ copyright © Adam L. G. Nevill 2011

‘Driving the Milky Way’ copyright © Weston Ochse 2011

‘The Windmill’ copyright © Rebecca Levene 2010, 2011

‘Moretta’ copyright © Garry Kilworth 2011

‘Hortus Conclusus’ copyright © Chaz Brenchley 2011

‘The Dark Space in the House in the House in the Garden

at the Centre of the World’ copyright © Robert Shearman 2011

‘The Muse of Copenhagen’ copyright © Nina Allan 2011

‘An Injustice’ copyright © Christopher Fowler 2011

‘The Room Upstairs’ copyright © Sarah Pinborough 2011

‘Villanova’ copyright © Paul Meloy 2011

‘Widow’s Weeds’ copyright © Christopher Priest, 2011

‘The Doll’s House’ copyright © Jonathan Green 2011

‘Inside/Out’ copyright © Nicholas Royle 2011

‘The House’ copyright © Eric Brown 2011

‘Trick of the Light’ copyright © Tim Lebbon 2011

‘What Happened to Me’ copyright © Joe R. Lansdale 2011

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

CONTENTS

Introduction, Jonathan Oliver

Objects in Dreams may be Closer than they Appear, Lisa Tuttle

Pied-à-terre, Stephen Volk

In the Absence of Murdock, Terry Lamsley

Florrie, Adam L. G. Nevill

Driving the Milky Way, Weston Ochse

The Windmill, Rebecca Levene

Moretta, Garry Kilworth

Hortus Conclusus, Chaz Brenchley

The Dark Space in the House in the House in the Garden at the Centre of the World, Robert Shearman

The Muse of Copenhagen, Nina Allan

An Injustice, Christopher Fowler

The Room Upstairs, Sarah Pinborough

Villanova, Paul Meloy

Widow’s Weeds, Christopher Priest

The Doll’s House, Jonathan Green

Inside/Out, Nicholas Royle

The House, Eric Brown

Trick of the Light, Tim Lebbon

What Happened to Me, Joe R. Lansdale

INTRODUCTION

I’ve never seen a ghost, I’ve never stayed in a haunted house, and I don’t believe in revenants seeking revenge from beyond the grave, yet the supernatural in fiction continues to fascinate me. There’s nothing better than the fright you get from a really good ghost story; certain scenes in Stephen King’s novel The Shining took my breath away and the last line of Ramsey Campbell’s classic ghost story, ‘The Trick,’ froze me with fear. However, while the ghost story has the fear of ‘the other’ at its heart, it is also fundamentally concerned with ourselves, for what are ghosts but the memories of lives lived and losses suffered? Grief and coping with loss are at the heart of several stories here: Chaz Brenchley explores the tragic death of a friend in ‘Hortus Conclusus’; in ‘An Injustice’ by Christopher Fowler, a haunting provides more than an intrepid group of ghost-hunters could have hoped for, while in ‘The Room Upstairs’ Sarah Pinborough explores a locked-room mystery through the sorrow of a grieving widow, and Eric Brown shows us that there is indeed a life after death in ‘The House.’

Revenge is often a theme that crops up in ghost stories and in this collection we have some unusual takes on this trope. ‘The Windmill’ by Rebecca Levene is a genuine howl of anger that speaks eloquently about crime and punishment; ‘Moretta’ by Garry Kilworth reveals an interesting twist that I certainly didn’t see coming the first time I read the tale, and while ‘Pied-à-terre’ by Stephen Volk isn’t necessarily a story of supernatural revenge, its warning from beyond certainly speaks of a desire for justice.

Ghosts as symbols of our own mortality also speak to us of ageing and the failure of the mortal flesh. This theme is chillingly and powerfully explored by two stories in this collection: ‘Florrie’ by Adam Nevill, in which the past tenant of a house draws the new owner into its influence, and ‘Trick of the Light’ by Tim Lebbon where the sight of a face at a window prompts a journey into darkness.

With two of our American contributors we have something a little more outré, an encounter with entities that may not be entirely human. The influence of Ray Bradbury is evident in a story that is really about a yearning for the hereafter and the fantastical, ‘Driving the Milky Way’ by Weston Ochse, while Joe R. Lansdale channels the spirit of Arthur Machen into a story that nevertheless has its roots in Texas. The figure of the unknowable other is also present in the Aickmanesque ‘The Muse of Copenhagen’ by the brilliant Nina Allan.

Let us not forget in our discussion of the supernatural, however, that the location of the haunting is often as important as the haunting itself. Lisa Tuttle’s unsettling ‘Objects in Dreams may be Closer than they Appear’ features a house that may or may not exist, but which still draws on the desires of the characters in the tale; ‘Villanova’ by Paul Meloy takes us on holiday to a static home in France, there to reveal a terrible family secret; ‘In The Absence of Murdock’ by Terry Lamsley features a very strange house and a haunting that verges on the comic and surreal; Jonathan Green takes us into the territory of gruesome horror with a visit to ‘The Doll’s House,’ while Robert Shearman’s ‘The Dark Space in the House in the House in the Garden at the Centre of the World’ sees our protagonists learning what it is to be human through their encounters with the supernatural.

Questions of what constitutes a haunting, and even what constitutes a house, are explored in the compelling and complex stories by Christopher Priest, ‘Widow’s Weeds’ in which a stage magician finds himself possessed by a most unusual haunting, and ‘Inside/Out’ by Nicholas Royle, where that which the protagonist perceives and the spaces he finds within and outside of himself comes together in a truly unsettling tale.

So now that you know what awaits you within, dear reader, it only remains for you to

step up the front door, knock and await for that which lives here to answer your call.

OBJECTS IN DREAMS MAY BE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR

Lisa Tuttle

Lisa Tuttle understands that, for a ghost story to work, it has to be as much about the human protagonists as any supernatural entities that arise. It’s all very well going for the scare or the sudden chill, but at the end of the day a house is a place where people live, whether it’s haunted or not. In the disturbing story that follows, Lisa writes about two people falling out of love and how the strange house they find affects them in a way they couldn’t even begin to imagine

Since we divorced twenty years ago, my ex-husband Michael and I have rarely met, but we’d always kept in touch. I wish now that we hadn’t. This whole terrible thing began with a link he sent me by e-mail with the comment, “Can you believe how much the old homestead has changed?”

Clicking on the link took me to a view of the cottage we had owned, long ago, for about three years – most of our brief marriage.

Although I recognized it, there were many changes. No longer a semi-detached, it had been merged with the house next-door, and also extended. It was, I thought, what we might have done ourselves given the money, time, planning permission and, most vitally, next-door neighbours willing to sell us their home. Instead, we had fallen out with them (they took our offer to buy as a personal affront) and poured too much money into so-called improvements, the work expensively and badly done by local builders who all seemed to be related by marriage if not blood to the people next-door.

Just looking at the front of the house on the computer screen gave me a tight, anxious feeling in my chest. What had possessed Michael to send it to me? And why had he even looked for it? Surely he wasn’t nostalgic for what I recalled as one of the unhappiest periods of my life?

At that point, I should have clicked away from the picture, put it out of my mind and settled down to work, but, I don’t know why, instead of closing the tab, I moved on down the road and began to discover what else in our old neighbourhood was different.

I’d heard about Google Earth’s ‘Street View’ function, but I’d never used it before, so it took me a little while to figure out how to use it. At first all the zooming in and out, stopping and starting and twirling around made me queasy, but once I got to grips with it, I found this form of virtual tourism quite addictive.

But I was startled by how different the present reality appeared from my memory of it. I did not recognize our old village at all, could find nothing I remembered except the war memorial – and that seemed to be in the wrong place. Where was the shop, the primary school, the pub? Had they all been altered beyond recognition, all turned into houses? There were certainly many more of those than there had been in the 1980s. It was while I was searching in vain for the unmistakable landmark that had always alerted us that the next turning would be our road, a commercial property that I could not imagine anyone converting into a desirable residence – the Little Chef – that it dawned on me what had happened.

Of course. The Okehampton bypass had been built, and altered the route of the A30. Our little village was one of several no longer bisected by the main road into Cornwall, and without hordes of holiday-makers forced to crawl past, the fast food outlet and petrol station no longer made economic sense.

Once I understood how the axis of the village had changed, I found the new primary school near an estate of new homes. There were also a couple of new (to me) shops: an Indian restaurant, wine bar, an oriental rug gallery, and a riding school. The increased population had pushed our sleepy old village slightly up-market. I should not have been surprised, but I suppose I was an urban snob, imagining that anyone living so deep in the country must be several decades behind the times. But I could see that even the smallest of houses boasted a satellite dish, and they probably all had broadband internet connections, too. Even as I was laughing at the garden gnomes on display in front of a neat yellow bungalow, someone behind those net curtains might be looking at my own terraced house in Bristol, horrified by what the unrestrained growth of ivy was doing to the brickwork.

Curious to know how my home appeared to others, I typed in my own address, and enjoyed a stroll around the neighbourhood without leaving my desk. I checked out a few less-familiar addresses, including Michael’s current abode, which I had never seen. So that was Goring-by-Sea!

At last I dragged myself away and wrote catalogue copy, had a long talk with one of our suppliers, and dealt with various other bits and pieces before knocking off for the day. Neither of us fancied going out, and we’d been consuming too many pizzas lately, so David whipped up an old favourite from the minimal supplies in the kitchen cupboard: spaghetti with marmite, tasty enough when accompanied by a few glasses of Merlot.

My husband David and I marketed children’s apparel and accessories under the name ‘Cheeky Chappies.’ It was exactly the sort of business I had imagined setting up in my rural idyll, surrounded by the patter of little feet, filling orders between changing nappies and making delicious, sustaining soups from the organic vegetables Michael planned to grow.

None of that came to pass, not even the vegetables. Michael did what he could, but we needed his income as a sales rep to survive, so he was nearly always on the road, which left me to take charge of everything at home, supervising the building work in between applying for jobs and grants, drawing up unsatisfactory business plans, and utterly failing in my mission to become pregnant.

Hard times can bring a couple together, but that is not how it worked for us. I grew more and more miserable, convinced I was a failure both as a woman and as a potential CEO. It did not help that Michael was away so much, and although it was not his fault and we needed the money, I grew resentful at having to spend so much time and energy servicing a house I’d never really wanted.

He’d drawn me into his dream of an old-fashioned life in the country, and then slipped out of sharing the major part of it with me. At the weekend, with him there, it was different, but most of the time I felt lonely and bored, lumbered with too many chores and not enough company, far from friends and family, cut off from the entertainments and excitement of urban existence.

Part of the problem was the house – not at all what we’d dreamed of, but cheap enough, and with potential to be transformed into something better. We’d been jumped into buying it by circumstances. Once Michael had accepted a very good offer on his flat (our flat, he called it, but it was entirely his investment) a new urgency entered into our formerly relaxed house-hunting expeditions. I had loved those weekends away from the city, staying in B&Bs and rooms over village pubs, every moment rich with possibility and new discoveries. I would have been happy to go on for months, driving down to the West Country, looking at properties and imagining what our life might be like in this house or that, but suddenly there was a time limit, and this was the most serious decision of our lives, and not just a bit of fun.

The happiest part of my first marriage now seems to have been compressed into half a dozen weekends, maybe a few more, as we travelled around, the inside of the car like an enchanted bubble filled with love and laughter, jokes and personal revelations and music. I loved everything we saw. Even the most impossible, ugly houses were fascinating, providing material for discussing the strangeness of other people’s lives. Yet although I was interested in them all, nothing we viewed actually tempted me. Somehow, I couldn’t imagine I would ever really live in the country – certainly not the practicalities of it. I expected our life to continue like this, work in the city punctuated by these mini-holidays, until we found the perfect house, at which point I’d stop working and start producing babies and concentrate on buying their clothes and toys and attractive soft furnishings and decorations for the house as if money was not and could never be a problem.

And then one day, travelling from the viewing of one imperfect property to look at another, which would doubtless be equally unsatisfactory in its own unique way, Blo

ndie in the cassette player singing about hanging on the telephone, we came to an abrupt halt. Michael stopped the car at the top of a hill, on one of those narrow, hedge-lined lanes that aren’t even wide enough for two normal sized cars to pass each other without the sort of jockeying and breath-holding maneuvers that in my view are acceptable only when parallel parking. I thought he must have seen another car approaching, and taken evasive action, although the road ahead looked clear.

“What’s wrong?”

“Wrong? Nothing. It’s perfect. Don’t you think it’s perfect?”

I saw what he was looking at through a gap in the hedge: a distant view of an old-fashioned, white-washed, thatch-roofed cottage nestled in one of those deep, green valleys that in Devonshire are called coombs. It was a pretty sight, like a Victorian painting you might get on a box of old-fashioned chocolates, or a card for Mother’s Day. For some reason, it made my throat tighten and I had to blink back sentimental tears, feeling a strong yearning, not so much for that specific house as for what it seemed to promise: safety, stability, family. I could see myself there, decades in the future, surrounded by children and grandchildren, dressed in clothes from Laura Ashley.

“It’s very sweet,” I said, embarrassed by how emotional I felt.

“It’s exactly what we’ve been looking for,” he said.

“It’s probably not for sale.”

“All it takes is the right offer.” That was his theory: not so much that everything had its price, as that he could achieve whatever goal he set himself. It was more about attitude than money.

“But what if they feel the same way about it as we do?”

“Who are ‘they’?”

“The people that live there.”

“But you feel it? What I feel? That it’s where we want to live?”