Full Throttle

Joe Hill

Dedication

For Ryan King, the daydreamer. I love you.

Contents

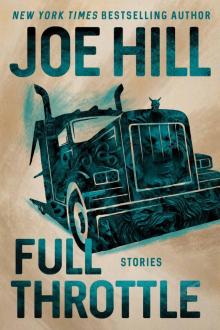

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction: Who’s Your Daddy?

Throttle (with Stephen King)

Dark Carousel

Wolverton Station

By the Silver Water of Lake Champlain

Faun

Late Returns

All I Care About Is You

Thumbprint

The Devil on the Staircase

Twittering from the Circus of the Dead

Mums

In the Tall Grass (with Stephen King)

You Are Released

Story Notes and Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Joe Hill

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Who’s Your Daddy?

WE HAD A NEW MONSTER every night.

I had this book I loved, Bring On the Bad Guys. It was a big, chunky paperback collection of comic-book stories, and as you might guess from the title, it wasn’t much concerned with heroes. It was instead an anthology of tales about the worst of the worst, vile psychopaths with names like The Abomination and faces to match.

My dad had to read that book to me every night. He didn’t have a choice. It was one of these Scheherazade-type deals. If he didn’t read to me, I wouldn’t stay in bed. I’d slip out from under my Empire Strikes Back quilt and roam the house in my Spider-Man Underoos, soggy thumb in my mouth and my filthy comfort blanket tossed over one shoulder. I could roam all night if the mood took me. My father had to keep reading until my eyes were barely open, and even then he could only escape by saying he was going to step out for a smoke and he’d be right back.

(My mother insists I developed childhood insomnia because of trauma. I took a snow shovel to the face at the age of five and spent a night in the hospital. In that era of lava lamps, shag carpets, and smoking on airplanes, parents weren’t allowed to stay overnight with their injured children at the hospital. The story goes that I woke, alone, in the middle of the night and couldn’t find them and tried to escape. Nurses caught me wandering the halls bare-assed and put me in a crib and strapped a net down over the top to keep me in. I screamed until my voice gave out. The story is so wonderfully horrible and gothic, I think we all need to assume it’s true. I only hope the crib was black and rusty and that one of the nurses whispered, “It’s all for you, Damien!”)

I loved the subhumans in Bring On the Bad Guys: demented creatures who shrieked unreasonable demands, raged when they didn’t get their way, ate with their hands, and yearned to bite their enemies. Of course I loved them. I was six. We had a lot in common.

My dad read me these stories, his fingertip moving from panel to panel so my weary gaze could follow the action. If you asked me what Captain America sounded like, I could’ve told you: he sounded like my dad. So did the Dread Dormammu. So did Sue Richards, the Invisible Woman—she sounded like my dad doing a girl’s voice.

They were all my dad, every one of them.

MOST SONS FALL INTO ONE of two groups.

There’s the boy who looks upon his father and thinks, I hate that son of a bitch, and I swear to God I’m never going to be anything like him.

Then there’s the boy who aspires to be like his father: to be as free, and as kind, and as comfortable in his own skin. A kid like that isn’t afraid he’s going to resemble his dad in word and action. He’s afraid he won’t measure up.

It seems to me that the first kind of son is the one most truly lost in his father’s shadow. On the surface that probably seems counterintuitive. After all, here’s a dude who looked at Papa and decided to run as far and as fast as he could in the other direction. How much distance do you have to put between yourself and your old man before you’re finally free?

And yet at every crossroads in his life, our guy finds his father standing right behind him: on the first date, at the wedding, on the job interview. Every choice must be weighed against Dad’s example, so our guy knows to do the opposite . . . and in this way a bad relationship goes on and on, even if father and son haven’t spoken in years. All that running and the guy never gets anywhere.

The second kid, he hears that John Donne quote—We’re scarce our fathers’ shadows cast at noon—and nods and thinks, Ah, shit, ain’t that the truth? He’s been lucky—terribly, unfairly, stupidly lucky. He’s free to be his own man, because his father was. The father, in truth, doesn’t throw a shadow at all. He becomes instead a source of illumination, a means to see the territory ahead a little more clearly and find one’s own particular path.

I try to remember how lucky I’ve been.

NOWADAYS WE TAKE IT FOR GRANTED that if we love a movie, we can see it again. You’ll catch it on Netflix or buy it on iTunes or splurge for the DVD box set with all the video extras.

But up until about 1980, if you saw a film in the theater, you probably never saw it a second time, unless it turned up on TV. You mostly rewatched pictures only in your memory—a treacherous, insubstantial format, although not entirely lacking in virtues. A fair number of films look best when seen in blurry memory.

When I was ten, my father brought home a Laserdisc machine, forerunner of the modern DVD player. He had also purchased three films: Jaws, Duel, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The movies came on these enormous, shimmering plates—they faintly resembled the lethal Frisbees that Jeff Bridges slung around in Tron. Each brilliant, iridescent platter had twenty minutes of video on each side. When a twenty-minute segment ended, my dad would have to get up and flip it over.

All that summer we watched Jaws, and Duel, and Close Encounters, again and again. Discs got mixed up: We’d watch twenty minutes of Richard Dreyfus scrabbling up the dusty slopes of Devil’s Tower to reach the alien lights in the sky, then we’d watch twenty minutes of Robert Shaw fighting the shark and getting bitten in half. Ultimately they became less like distinct narratives and more a single bewildering quilt of story, a patchwork of wild-eyed men clawing to escape relentless predators, looking to the star-filled sky for rescue.

When I went swimming that summer, and dived beneath the surface of the lake, and opened my eyes, I was sure I’d see a great white lunging out of the dark at me. More than once I heard myself screaming underwater. When I wandered into my bedroom, I half expected my toys to spring to antic, supernatural life, powered by the energy radiating from passing UFOs.

And every time I went for a drive with my father, we played Duel.

Directed by a barely twenty-year-old Steven Spielberg, Duel was about a nebbish everyman in a Plymouth (Dennis Weaver), driving frantically across the California desert, pursued by a nameless, unseen trucker in a roaring Peterbilt tanker. It was (and still is) a sun-blasted work of faux Hitchcock and a chrome-plated showcase for its director’s bottomless potential.

When my dad and I went out for a drive, we liked to pretend the truck was after us. When this imaginary truck hit us from behind, my dad would stomp on the gas to pretend we’d been struck or sideswiped. I’d fling myself around in the passenger seat, screaming. No seat belt, of course. This was maybe 1982, 1983? There’d be a six-pack of beer on the seat between us . . . and when my dad finished one can, the empty went out the window, along with his cigarette.

Eventually the truck would mash us and my dad would make a screaming-shrieking sound and weave this way and that along the road, to indicate we were dead. He might drive for a full minute with his tongue hanging out and his glasses askew to indicate the truck had schmucked him good. It was always a blast, dying on the road together, the father and the son and the unholy Eighteen-Wheeler of Evil.

MY DAD READ TO ME a

bout the Green Goblin, but my mother read to me about Narnia. Her voice was (is) as calming as the first snowfall of the year. She read about betrayal and cruel slaughter with the same patient certainty that she read about resurrection and salvation. She is not a religious woman, but to hear her read is to feel a little as if you’re being led into a soaring Gothic cathedral, filled with light and a roomy sense of space.

I remember Aslan dead on the stone and the mice nibbling at the ropes that bound his corpse. I think that provided me with my foundational sense of decency. To live a decent life is to be no more than a mouse nibbling at a rope. One mouse isn’t much, but if enough of us keep chewing, we may set something free that can save us from the worst. Maybe it will even save us from ourselves.

I also still believe that books operate along the same principles as enchanted wardrobes. You climb into that little space and come out the other side in a vast and secret world, a place both more frightening and more wonderful than your own.

MY PARENTS DIDN’T JUST READ stories—they wrote them, too, and as it happened, they were both very good at it. My dad was so successful at it they put him on the cover of Time magazine. Twice! They said he was America’s boogeyman. By then Alfred Hitchcock was dead, so somebody had to be. My dad didn’t mind. America’s boogeyman is a good-paying gig.

Directors were turned on by my father’s ideas, and producers were turned on by money, so a lot of the books were made into films. My father became friends with a well-regarded independent filmmaker named George A. Romero. Romero was the shaggy, rebel auteur who kind of invented the zombie apocalypse with his film Night of the Living Dead, who kind of forgot to copyright it, and who, as a result, kind of didn’t get rich off it. The makers of The Walking Dead will be forever grateful to Romero for being so good at directing and so bad at protecting his intellectual property.

George Romero and my father dug the same kind of comic books: the nasty, bloody ones that were published in the 1950s before a bunch of senators and shrinks teamed up to make childhood boring again. Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear.

Romero and my dad decided to make a film together—Creepshow—that would be like one of those horror comics, only in movie form. My dad even played a part in it: He was cast as a man who gets infected with an alien pathogen and begins turning into a plant. They were filming in Pittsburgh, and I guess Dad didn’t want to be lonely, so he brought me along, and they stuck me in the film, too. I played a kid who murders his father with a voodoo doll, after Dad takes his comic books away. In the movie my dad is Tom Atkins, who in real life is too affable and easygoing to murder.

The movie was full of big gross-out moments: severed heads, bodies swollen with cockroaches splitting in two, animated corpses dragging their way up out of the muck. Romero hired an artist of assassination to do the special makeup effects: Tom Savini, the same wizard of nasty who crafted the zombies in Dawn of the Dead.

Savini wore a black leather motorcycle jacket and motorcycle boots. He had a satanic goatee and arched, Spock-like eyebrows. There was a shelf of books in his trailer full of autopsy photos. He wound up with two jobs on Creepshow: doing special makeup effects, and babysitting me. I spent a whole week camped out in his trailer, watching him paint wounds and sculpt claws. He was my first rock star. Everything he said was funny and also, weirdly, true. He had gone to Vietnam, and he told me he was proud of what he accomplished there: not getting himself killed. He thought that revisiting slaughter in film was like therapy, only he got paid for it.

I watched him turn my dad into a swamp thing. He planted moss in my father’s eyebrows, attached shaggy brush to his hands, put an artful clump of grass on his tongue. For half a week, I didn’t have a dad, I had a garden with eyes. In my memory he smells of the wet soil beneath a heap of autumn leaves, but that’s probably my imagination working.

Tom Atkins had to fake-slap me, and Savini painted a hand-shaped bruise on my left cheek. The filming went late that night, and when we left the set, I was starved. My father drove me to a nearby McDonald’s. I was overtired and cranked up and hopping up and down, shouting that I wanted a chocolate milk shake, that he promised a milk shake. At some point my father realized that half a dozen McDonald’s employees were staring at us with haunted, accusing looks. I still had that handprint on my face, and he was out at one in the morning to get me a milk shake as . . . what? A bribe not to report him for child abuse? He got out of there before someone could call Child Protective Services on him, and we didn’t have McDonald’s again until after we left Pittsburgh.

By the time my dad had us heading for home, I knew two things. The first is that I probably had no real future as an actor, and neither did my dad (sorry, Dad). The second is that even if I couldn’t act to save a rat’s ass, I had nevertheless found my calling, a purpose in my life. I had spent seven solid days watching Tom Savini slaughter people artistically and invent unforgettable, deformed monsters, and that’s what I wanted to do, too.

And it is, actually, what I wound up doing.

Which is getting me around to what I wanted to say in this introduction: A child has only two parents, but if you’re lucky enough to get to be an artist for a living, ultimately you wind up with a few mothers and fathers. When someone asks a writer “Who’s your daddy?” the only honest answer is “That’s complicated.”

IN HIGH SCHOOL I KNEW jocks who read every issue of Sports Illustrated cover to cover and rockers who pored over each issue of Rolling Stone like the devout studying Scripture. Me, I read four years of Fangoria magazine. Fangoria—Fango to the faithful—was a journal dedicated to splatter flicks, pictures like John Carpenter’s The Thing, Wes Craven’s Shocker, and quite a few films with the name Stephen King featured in the title. Every issue of Fango included centerfolds, just like an issue of Playboy, only instead of some babe opening her legs, you had some psychopath opening a head with an ax.

Fango was my guidebook to the all-important sociopolitical debates of the 1980s, such as: Was Freddy Krueger too funny? What was the grossest picture ever made? And, crucially, would there ever be a better, nastier, more bone-splitting werewolf transformation than the one in American Werewolf in London? (The answers to the first two questions are open to debate—the answer to the third, is, simply, no.)

I was just about impossible to scare, but American Werewolf did the next best thing: It stirred in me a sense of dreadful gratitude. It seemed to me that the movie had put its hairy paw on an idea that lurks under the surface of all the truly great horror stories. Namely, that to be a human being is to be a tourist in a cold, unfriendly, and ancient country. Like all tourists we hope for a lark . . . a few laughs, a bit of adventure, a roll in the hay. But it’s so easy to get lost. The day ends so quickly, and the roads are so confusing, and there are things out there in the dark with teeth. To survive we might have to show some teeth of our own.

Around the time I started reading Fangoria, I also started to write, every day. To me it just seemed like the normal thing to do. After all, when I got home from school and wandered into the house, my mother was always at it, sitting behind her tomato-colored IBM Selectric, making stuff up. My father would be at it, too, hunched close to the screen of his Wang word processor, the most futuristic device he had brought home since the Videodisc player. The screen was the blackest black in the history of black, and the words on the monitor were rendered in green letters the color of toxic radiation in sci-fi films. At dinner the talk was all of make-believe, of characters, settings, twists, and scenarios. I observed my folks at work, listened in on their table talk, and came to a logical conclusion: If you sat by yourself and made things up for a couple hours every day, sooner or later someone would pay you a lot of money for your trouble. Which, as it happened, turned out to be true.

If you Google “How do I write a book?” you’ll get a million hits, but here’s the dirty secret: It’s just math. It’s not even hard math—it’s first-grade addition. Write three pages a day, every day

. In a hundred days, you’ll have three hundred pages. Type “The End.” Done.

I wrote my first book at fourteen. It was called Midnight Eats, and it was about a private academy where the elderly cafeteria ladies chopped up students and fed them to the rest of the kids in school for lunch. They say you are what you eat—I ate Fango and wrote something with all the literary merit of a straight-to-video splatter flick.

I don’t think anyone managed to read the thing all the way to the end, except possibly my mother. As I said, writing a book is just math. Writing a good book, that’s something else entirely.

I WANTED TO LEARN MY CRAFT, and I had not one but two brilliant writers living under the same roof with me—not to mention novelists of all stripes walking through the door every other day. Forty-Seven West Broadway, Bangor, Maine, had to be the world’s best unknown writing school, but it was mostly wasted on me, for two good reasons: I was a bad listener and a worse student. Alice, lost in Wonderland, observes that she often gives herself good advice but very rarely takes it. I get that. I heard a lot of great advice as a kid and never took any of it.

Some people are visual learners; some people can glean lots of helpful information from lectures or classroom discussion. Me, everything I ever figured out about writing stories, I learned from books. My brain doesn’t move fast enough for conversation, but words on a page will wait for me. Books are patient with slow learners. The rest of the world isn’t.

My parents knew I loved to write and wanted me to succeed and understood that sometimes trying to explain things to me was like talking to a dog. Our corgi, Marlowe, could understand a few important words, like “walk” and “eat,” but really, that was about it. I can’t say I was much more developed. So my folks bought me two books.

My mother got me Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury, and while the book is full of fine suggestions for unlocking one’s creativity, what really turned my head was the way it was written. Bradbury’s sentences went off like strings of firecrackers erupting on a hot July night. Discovering Bradbury felt a bit like that moment in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy steps out of the barn and into the world just over the rainbow—it was like moving from a black-and-white room into a land where everything is in Technicolor. The medium was the message.