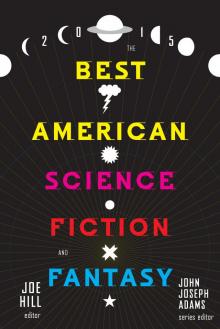

The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015

Joe Hill

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Foreword

Introduction: Launching Rockets

SOFIA SAMATAR, How to Get Back to the Forest

CARMEN MARIA MACHADO, Help Me Follow My Sister into the Land of the Dead

CAT RAMBO, Tortoiseshell Cats Are Not Refundable

KAREN RUSSELL, The Bad Graft

ALAYA DAWN JOHNSON, A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i

SEANAN MCGUIRE, Each to Each

SOFIA SAMATAR, Ogres of East Africa

THEODORA GOSS, Cimmeria: From the Journal of Imaginary Anthropology

JO WALTON, Sleeper

NEIL GAIMAN, How the Marquis Got His Coat Back

SUSAN PALWICK, Windows

ADAM-TROY CASTRO, The Thing About Shapes to Come

SAM J. MILLER, We Are the Cloud

DANIEL H. WILSON, The Blue Afternoon That Lasted Forever

NATHAN BALLINGRUD, Skullpocket

KELLY LINK, I Can See Right Through You

JESS ROW, The Empties

KELLY SANDOVAL, The One They Took Before

T. C. BOYLE, The Relive Box

A. MERC RUSTAD, How to Become a Robot in 12 Easy Steps

Contributors’ Notes

Other Notable Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories of 2014

Read More from The Best American Series®

About the Editors

Copyright © 2015 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

Introduction copyright © 2015 by Joe Hill

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Best American Series® is a registered trademark of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy™ is a trademark of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the proper written permission of the copyright owner unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. With the exception of nonprofit transcription in Braille, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt is not authorized to grant permission for further uses of copyrighted selections reprinted in this book without the permission of their owners. Permission must be obtained from the individual copyright owners as identified herein. Address requests for permission to make copies of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt material to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

ISBN 978-0-544-44977-0

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

eISBN 978-0-544-44984-8

v1.1015

“Skullpocket” by Nathan Ballingrud. First published in Nightmare Carnival, October 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Nathan Ballingrud. Reprinted by permission of Nathan Ballingrud.

“The Relive Box” by T. Coraghessan Boyle. First published in The New Yorker, March 17, 2014. Copyright © 2014 by T. Coraghessan Boyle. Reprinted by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc., on behalf of the author.

“The Thing About Shapes to Come” by Adam-Troy Castro. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, January 2014 (Issue 44). Copyright © 2014 by Adam-Troy Castro. Reprinted by permission of Adam-Troy Castro.

“How the Marquis Got His Coat Back” by Neil Gaiman. First published in Rogues. Copyright © 2014 by Neil Gaiman. Reprinted by permission of Neil Gaiman.

“Cimmeria: From the Journal of Imaginary Anthropology” by Theodora Goss. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, July 2014 (Issue 50). Copyright © 2014 by Theodora Goss. Reprinted by permission of Theodora Goss.

“A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i” by Alaya Dawn Johnson. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/August 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Alaya Dawn Johnson. Reprinted by permission of Alaya Dawn Johnson.

“I Can See Right Through You” by Kelly Link. First published in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, no. 48, December 2014, and reprinted in Get in Trouble: Stories by Kelly Link (Random House, 2015). Copyright © 2014 by Kelly Link. Reprinted by permission of Kelly Link.

“Help Me Follow My Sister into the Land of the Dead” by Carmen Maria Machado. First published in Help Fund My Robot Army!!! And Other Improbable Crowdfunding Projects. Copyright © 2014 by Carmen Maria Machado. Reprinted by permission of Carmen Maria Machado.

“Each to Each” by Seanan McGuire. First published in Lightspeed Magazine: Women Destroy Science Fiction!, June 2014 (Issue 49). Copyright © 2014 by Seanan McGuire. Reprinted by permission of Seanan McGuire.

“We Are the Cloud” by Sam J. Miller. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, September 2014 (Issue 52). Copyright © 2014 by Sam J. Miller. Reprinted by permission of Sam J. Miller/Lightspeed.

“Windows” by Susan Palwick. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, September 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Susan Palwick. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Tortoiseshell Cats Are Not Refundable” by Cat Rambo. First published in Clarkesworld Magazine, February 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Catherine Rambo. Reprinted by permission of Cat Rambo.

“The Empties” by Jess Row. First published in The New Yorker, November 3, 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Jess Row. Reprinted by permission of Denise Shannon Literary Agency, Inc.

“The Bad Graft” by Karen Russell. First published in The New Yorker, June 9, 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Karen Russell. Reprinted by permission of Denise Shannon Literary Agency, Inc.

“How to Become a Robot in 12 Easy Steps” by A. Merc Rustad. First published in Scigentasy, March 1, 2014 (Issue 4). Copyright © 2014 by A. Merc Rustad. Reprinted by permission of Merc Rustad, author.

“How to Get Back to the Forest” by Sofia Samatar. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, March 2014 (Issue 46). Copyright © 2014 by Sofia Samatar. Reprinted by permission of Sofia Samatar.

“Ogres of East Africa” by Sofia Samatar. First published in Long Hidden. Copyright © 2014 by Sofia Samatar. Reprinted by permission of Sofia Samatar.

“The One They Took Before” by Kelly Sandoval. First published in Shimmer Magazine, December 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Kelly Sandoval. Reprinted by permission of Kelly Sandoval.

“Sleeper” by Jo Walton. First published on Tor.com, August 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Jo Walton. Reprinted by permission of Jo Walton.

“The Blue Afternoon That Lasted Forever” by Daniel H. Wilson. First published in Carbide Tipped Pens, December 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Daniel H. Wilson. Reprinted by permission of Daniel H. Wilson.

Foreword

THE PRIMARY REASON this volume exists is a novel I read when I was eighteen years old: The Stars My Destination, by Alfred Bester.

I’d read a number of science fiction novels that I liked a great deal—books that I remember fondly to this day—but it wasn’t until The Stars My Destination that I realized the heights that science fiction could attain.

That prose!

Those ideas!

That goddamn sense of wonder!

My entire reading life was forever changed—it became all about finding other books like that one.

In Bester’s classic, there’s a paragraph early on that describes “common man” protagonist Gully Foyle’s state of mind. A disaster has stranded him, the lone survivor, on a spaceship for 170 days. On day 171 another ship approaches his, ignores his distress call, and leaves him there to die:

He had reached a dead end. He had been content to drift from moment to moment of existence for thirty years like some hea

vily armored creature [. . .] but now he was adrift in space for one hundred and seventy days, and the key to his awakening was in the lock.

In that moment Gully Foyle found new purpose and rebuilt his previously aimless existence into something entirely new.

That was the key to his awakening. I think of The Stars My Destination as mine.

This is a story I’ve told before—my origin story, if you will. The catalyst for what I was to become. Now my existence is all about finding stories that can make that same kind of impact—stories that are so good they make your eyes flicker with lightning, stories that demand you quote bits and pieces to your friends and to the larger world via social media, stories that once you read them, they become a part of you . . . stories that turn that key.

I’m new here, so let me introduce myself: I’m John Joseph Adams. I first started working in the science fiction and fantasy field in 2001, when I got a job as an editorial assistant at one of the genre’s leading magazines, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (founded in 1949, publisher of my all-time favorite story, “Flowers for Algernon”). In 2008 I published my first anthology, Wastelands; since then I’ve published more than twenty anthologies, launched two magazines (Lightspeed and Nightmare), cofounded Wired.com’s The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy podcast, and been nominated for—or edited stories that were nominated for—numerous awards and honors, including the World Fantasy, Hugo, and Nebula Awards. All of which led to my being selected to serve as the series editor of The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy.

Science fiction and fantasy are also new here, so let me introduce them as well.

Science fiction and fantasy (or SF/F as I will henceforth refer to them in this foreword) can be notoriously tricky to define—so much so that Damon Knight, founder of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (the professional SF/F writers’ organization, which presents the Nebula Awards), once famously said, “Science fiction is what we point to when we say it.”

Obviously that’s not a very useful definition, but it speaks to how thorny a proposition it is to provide a concrete definition of the genre. Also, Knight mentions only science fiction, but fantasy is essentially implied. Which might seem strange, since at first you might think that science fiction and fantasy are two distinct, and in some ways opposing, genres. But the more you drill down to their core attributes, the clearer it becomes that they’re part and parcel of the same whole—which is why they’re so often paired together, as they are in this volume.

SF/F—which sometimes is collectively referred to by the larger umbrella term “speculative fiction”—essentially comprises stories that start by asking the question What if . . . ? What if one of the fundamental operating principles of the universe didn’t work the way we actually think it does? What if technology existed that enabled you to upload your consciousness to a computer? What if the creatures from our myths and legends actually existed?

From there, SF/F is often broken down into subgenres, many of which even the most casual genre fan is likely aware of—if not by name, then by example. These include space opera (Star Wars), urban fantasy (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), military science fiction (Starship Troopers), epic fantasy (Lord of the Rings), dystopian fiction (1984), fairy tales (Once Upon a Time), postapocalyptic fiction (Mad Max), magical realism (Pan’s Labyrinth), time travel (12 Monkeys), steampunk (Wild Wild West), portal fantasy (Chronicles of Narnia), sword and sorcery (Conan the Barbarian), and many others.

(Obviously, I could have dropped a lot of deep-geek literary references there to describe these subgenres, but I tried to stick with examples from movie and television pop culture to help ensure that everyone groks what I mean. Well, except for that reference. Grok is science fiction geek for “understand,” as coined by Robert A. Heinlein in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land.)

Thus far I’ve talked about the similarities of science fiction and fantasy, but what of the differences between them? This question, too, is often difficult to answer and frequently fraught with debate.

Fantasy is generally the easier of the two to define clearly: fantasy stories are stories in which the impossible happens. The easiest (and perhaps most common) example to illustrate this is that magic is real and select humans can wield or manipulate it. Sometimes such stories take place in secondary worlds (as in Lord of the Rings), but other times they take place in a world very much like our own but with one or two key changes to the way the world works. To use one example from this anthology to illustrate the latter: you might have a world where everything is normal until suddenly, out of nowhere, people start having babies shaped like cubes and other geometrical objects.

Science fiction has the same starting point as fantasy—stories in which the impossible happens—but adds a crucial twist: science fiction is stories in which the currently impossible but theoretically plausible happens (or, in some cases, things that are currently possible but haven’t happened yet). The foremost pop culture example that probably leaps to the minds of most people is Star Trek—and indeed its idea of traveling among the stars on spaceships, seeking “strange new worlds,” is a common one in science fiction—but there’s much more variety to it than that. Science fiction runs the gamut from near-future scenarios like “What if you could record every moment of your life and replay memories any time you want?” to genetically engineering soldiers to operate better in alien environments to examining what life would be like after the artifice of human civilization crumbles.

But to talk about the definition of SF/F without discussing where it came from would be to do the genre a disservice. (And I hope hard-core genre fans and historians will forgive me as I gloss over large swaths of its history as I attempt to do the impossible and synopsize the development of two genres in a few hundred words.)

Several examples of proto–science fiction precede it, but our contemporary understanding of science fiction more or less begins in the nineteenth century, with notable early practitioners such as H. G. Wells (The Time Machine) and Jules Verne (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea). Many, such as SF author and historian Brian Aldiss, consider Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to be the first science fiction novel (though Shelley was not and is not generally thought of as a science fiction writer). The fantasy tradition has roots in myth and legends and thus can trace its origins as far back as classics like the Odyssey, but our understanding of modern fantasy is mostly shaped by the works of authors such as George MacDonald (The Princess and the Goblin), Lord Dunsany (The King of Elfland’s Daughter), L. Frank Baum (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz), and Lewis Carroll (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland).

But it was in the early twentieth century that the genres truly began to flourish as an art form, especially in the realm of short fiction, thanks in large part to the founding of the magazines Weird Tales (in 1923), which frequently published works by the likes of H. P. Lovecraft (“The Call of Cthluhu”) and Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian), and Amazing Stories (in 1926), by Hugo Gernsback (namesake of the genre’s Hugo Award). Editors such as John W. Campbell at Astounding (which continues to this day under the title Analog) went on to push and shape the genre, and a strong focus on literary storytelling emerged in 1949 with The Magazine of Fantasy (later The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction), under Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas. The field continued to develop and evolve over the years, with notable movements such as the New Wave, which sought to explore experimental narrative devices and placed a strong emphasis on literary quality. And any partial history of the development of SF/F would be incomplete without acknowledging the critical impact of the landmark anthology Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison, on the field.

This new Best American series is a major milestone for a genre that has at times struggled for literary respectability—despite the fact that it is the genre of the aforementioned “Flowers for Algernon,” that it is the genre of the innumerable classics of Ray Bradbury (“All Summer in a Day”), Ursula K. Le Guin (“The Ones Who Walk Aw

ay from Omelas”), Shirley Jackson (“The Lottery”), Harlan Ellison (“‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman”), Octavia E. Butler (“Bloodchild”), and Kurt Vonnegut (“Harrison Bergeron”).

But science fiction and fantasy literature is currently experiencing a golden age; there’s more high-quality genre literature being written now than ever before. And science fiction and fantasy themes have broken through the boundaries of other genres as well, figuring prominently in numerous mainstream bestsellers both in the literary fiction category and in film and television. That makes now the perfect time for SF/F to join the Best American family.

Many popular mainstream books in recent years have been infused with science fiction and fantasy elements—Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones, Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. Some, such as Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, have not only been popular but have won the Pulitzer Prize as well. Many readers would not classify some of these novels as genre books, yet it is undeniable that they are genre; if you removed the SF/F element from any of them, the stories would fall apart. Furthermore, within the SF/F community, these novels have already been accepted as part of the field.

Part of the scope of this anthology series will be to help define—and redefine—just what science fiction and fantasy is capable of. It is my opinion that the finest science fiction and fantasy is on a par with the finest works of literature in any genre, and the goal of this series is to prove it.

The stories chosen for this anthology were originally published between January 2014 and December 2014. The technical criteria for consideration are (1) original publication in a nationally distributed American or Canadian publication (that is, periodicals, collections, or anthologies, in print, online, or as an ebook); (2) publication in English by writers who are American or Canadian or who have made the United States their home; (3) publication as text (audiobooks, podcasts, dramatizations, interactive works, and other forms of fiction are not considered); (4) original publication as short fiction (excerpts of novels are not knowingly considered); (5) length of 17,499 words or less; (6) at least loosely categorized as science fiction or fantasy; (7) publication by someone other than the author (self-published works are not eligible); and (8) publication as an original work of the author (not part of a media tie-in/licensed fiction program).