The Monkey's Wedding

Joan Aiken

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Making of a Storyteller

A Mermaid Too Many

Reading in Bed

Model Wife

Second Thoughts

Girl in a Whirl

Hair

Red-Hot Favourite

Spur of the Moment

The Paper Queen

Octopi in the Sky

The Magnesia Tree

Honeymaroon

Harp Music

The Sale of Midsummer

The Helper

The Monkey’s Wedding

Wee Robin

The Fluttering Thing

Water of Youth

Acknowledgments

Publication History

The Monkey’s Wedding

and other

stories

Joan Aiken

with Introductions from

Joan Aiken and Lizza Aiken

Small Beer Press

Easthampton, MA

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed

in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

The Monkey’s Wedding and Other Stories copyright © 2011 by Joan Aiken Estate (John Sebastian Brown & Elizabeth Delano Charlaff). All rights reserved.

“Model Wife,” “Girl in a Whirl,” “A Mermaid Too Many,” “Red-Hot Favourite,” “Spur of the Moment,” “Octopi in the Sky,” “Honeymaroon,” “Water of Youth” copyright © 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961 by Joan Aiken. All rights reserved.

“The Sale of Midsummer,” “Introduction,” “The Monkey’s Wedding,” “The Helper,” “Wee Robin” copyright © 1976, 1996, 1996, 1979, 2002 by Joan Aiken Enterprises. All rights reserved.

“Reading in Bed,” “Hair,” “Harp Music,” “The Magnesia Tree,” “Second Thoughts,” “The Paper Queen,” “The Fluttering Thing” copyright © 2011 by Joan Aiken Estate (John Sebastian Brown & Elizabeth Delano Charlaff). All rights reserved.

“Introduction by Lizza Aiken” copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth Delano Charlaff. All rights reserved.

Small Beer Press

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

smallbeerpress.com

weightlessbooks.com

[email protected]

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aiken, Joan, 1924-2004.

The monkey’s wedding, and other stories / Joan Aiken. -- 1st ed.

p. cm.

isbn 978-1-931520-74-4 (alk. paper)

I. Title.

pr6051.i35m66 2011

823’.914--dc22

2011004625

First edition 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Text set in Minion 12 pt.

The trade cloth edition of this book was printed on 30% PCR recycled paper by Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI.

Author photo © Rod Delroy.

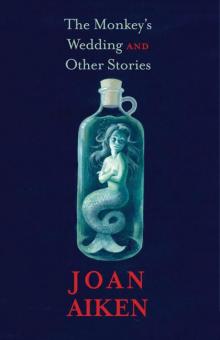

Cover painting by Shelley Jackson (ineradicablestain.com).

Introduction

Writing short stories has always been my favourite occupation ever since I was small, when I used to tell stories to my younger brother on walks we took through the Sussex woods and fields. At first I told him stories out of books we had in the house and then, running low on these, I began to invent, using the standard ingredients, witches, dragons, castles. Then doors began to open: in my mind, I realised that the stories could be enriched and improved by mixing in everyday situations, people catching trains, mending punctures in bicycle tyres, winning raffles, getting medicine from the doctor. Then I began mixing in dreams. I have always had wonderful dreams—not as good as those of my father Conrad Aiken, who was the best dreamer I ever met, but very striking and full of mystery and excitement. The first story I ever finished, written at age six or seven, was taken straight from a dream. It was called Her Husband was a Demon. And one of my full-length books, Midnight is a Place, was triggered off by a formidable dream about a carpet factory. Most of my short stories have some connection with a dream. When I wake I jot down the important element of the dream in a small notebook. Then weeks, months, even years may go by before I use it, but in the end a connection will be made with something that is happening now, and that sets off a story. It is rather like mixing flour and yeast and warm water. All three ingredients, on their own, will stay unchanged, but put them together and fermentation begins. A short story is not planned, in the way that a full-length novel is planned, episode by episode, with the end I sight; a short story is given, straight out of nowhere: suddenly two elements combine and the whole pattern is there, in the same way as, I imagine, painters get a vision of their pictures, before work starts. A short story, to me, always has a mysterious component, something that appears inexplicably from nowhere. Inexplicably, but inevitably; for if you check back through the pattern of the story, you can see that the groundwork has already been laid for it. The story of “The Monkey’s Wedding,” for example, was set in motion by a dream about an acerbic old lady hunting about her house for lost things and buried memories, combined with a news story about a valuable painting found abandoned in a barn; only after I had begun the story did I realise that the last ingredient was going to be a grandson she didn’t even know she had lost.

Joan Aiken, 1995

The Making of a Storyteller

This collection of stories, some of which have never been published before, is taken mostly from Joan Aiken’s earliest writing years in the 1950s and 1960s when she was working for the English short-story magazine, Argosy. They demonstrate her wide ranging stylistic ability, with subjects as diverse as a spinster castaway on an island of talking mice, a doctor’s cure for a glamorous man-hating motorcycle stunt rider, a village that appears only for three days a year, or a vicar happily reincarnated as a devilish cat. All these ideas seem to pour out of an endless imagination, making bold use of eccentric and unexpected settings and characters, and at the same time demonstrating an evident delight in parodying a variety of literary styles from gothic to comedy, fantasy to folktales. But Joan always repudiated the suggestion that she was “a born storyteller.” She would always argue furiously that writing was a craft, like oil painting or cabinetmaking, that she had learned, practiced, and developed over the years. She described this period of her life as a single-minded engagement with the writer’s craft; and her grasp of the short-story form as the foundation of her literary career.

What is far from apparent from these wildly inventive and freewheeling tales is that this was in fact a bitterly difficult period of her life, when not long after the end of the Second World War she was left widowed and homeless with two young children. Having made the brave decision to try and support herself and her family by writing, she applied for a job at a popular short-story magazine. In many ways, as she often said subsequently, this period spent working at Argosy could not have been bettered, both as a wonderful distraction and consolation during a bad time, and as an unbeatable apprenticeship in the craft of writing.

Joan’s work on the magazine, as a very junior jack-of-all-trades, gave her a thorough editorial training while teaching her more than she had ever learned at school about the basics of grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Her chief task was to read dozens of stories from the hundreds of submissions that arrived in daily bales, and then to reply to the unsuccessful budding authors. She gave critical feedback and advice, while also learning a good deal in the process about what made a good story. Joan also met and interviewed for Argosy many of the successful authors of the time, talking to writers such as H. E. Bates, Paul Gallico, Ray Bradbury, and Geoffrey Household about their working methods. Finally, she was also able to supplement her fairly meag

er income by contributing all kinds of articles to the magazine: editorial pieces, poems, anthology features, and eventually, also the short stories she was starting to write herself. It was this fertile mix of potboilers and random pieces, rapidly invented space fillers, articles written to go with leftover illustrations, and cheerfully ironic commentaries on unusual news stories or eccentric scientific inventions, which really began to inform Joan’s fiction and ignite her practically unstoppable powers of invention.

Under a variety of pen names, including the nicely tongue-in-cheek John Silver—a name stolen from the pirate in Treasure Island—Joan created some of her taller tales. Among these was a piece imagining, for example, the plot for a stage musical constructed entirely from the personal columns of a daily paper:

“Nick Lochinvar, a young Scot, is broke and broken-hearted. Owing to a revolution he has had to leave the independent Indian kingdom of Pawncore, where he was agent-general, and Kate, the girl he adored, who has stayed to look after the little prince, and taking only his pet mamba, Amanda. (Yes yes, we know you don’t get mambas in India, but he had been in Africa first.) In a mood of black despair he turns to studying the psychology of donkeys. Finally, reduced to selling either his Scottish evening full-dress regalia or the faithful Amanda, he spots an advertisement for a snake-charming competition the prize for which, five thousand pounds, would allow him to restore his fortunes with Kate . . .”

—and much more, material enough for a sackful of stories. Suggested lyrics to the songs are included of course, for example “the tune that he croons in the rainy monsoon—‘I’ve a bungalow deep in the jungle-o . . .’” which also pour out in the astonishing flow of her invention.

Joan imagined the publication of a simple ‘First Reader’ for the educational improvement of long-term prison inmates, with lines like:

“Has Dan got a hot rod?”

“No, but Ned can do a ton in his van. . . .”

“Run Jim run! I saw a cop pop out of the pub!”

Or she would create and describe entirely fictitious manuals, with names such as Popular Errors Explained, from which she would list an astonishing selection of ‘quotations’ from topics in the index—‘Crocodile, Death foreboded by sight of,’ or ‘Nine of Diamonds, the curse of Scotland,’ or simply ‘Absurd Notions, Universal . . .’ All, of course, were invented to tickle the imagination of the reader, but at the same time such pieces were developing possibilities for mad plots in her own fiction.

This need for quick-fire creativity clearly fed Joan’s fertile mind and produced endlessly zany plots, as can be seen from the subjects of the tall tales included in this collection—a sailor who brings home a mermaid in a bottle, the murderous nightmares of the advertising jingle writer. Every story is surprising in its premise but promises an even more extraordinary outcome, once you are acclimatized to the Aiken imagination.

Reading dozens of stories daily provided a perfect opportunity to study both what made appealing story content, and also what made a story memorable. Joan summed up the story-writing formula she worked out for the necessary combination of elements as “exotic background, touch of sex, twist ending, and a touch of humor if possible”—a formula that would enable her to sell as many stories as she could in order to keep the family afloat.

As well as learning to write fast and efficiently, Joan was also working to perfect her style. In her interview with H. E. Bates, she notes a remark of his that became one of her key precepts for short-story writing. She writes:

“Besides inspiration and a lot of sheer hard labor, a story requires, for its germination, at least two separate ideas which, fusing together, begin to work and ferment and presently produce a plot.”

Apart from scanning the small ads for inspiration, Joan always recommended keeping a notebook to record odd sights and overheard conversations, dreams and news items that would presently gel into a plot. She found that this moment of congruence often came, in her case, while she was dealing with household chores, although she noted wryly that “other writers like Coleridge took laudanum, Kipling sharpened pencils, or Turgenev sat with his feet in a bucket of hot water” while waiting for the inspiration to strike.

Beyond thoughts on plots, Joan records very definite principles on style, for example comparing the construction of a short story to that of a small fire:

“You are trying to kindle the reader’s interest, feeding it with little nourishing bits of fuel, not dumping on too much at once. Lots of people when they begin writing make the mistake of putting in too much description—describing is lovely—but the reader can only take so much at one time, and he will begin to skip.”

Another basic piece of advice she gives is to “show things—don’t just tell the reader about them. If your hero is stingy and selfish—or if the house where he lives is haunted—show it, show what happens” and this she carries out with relish. With true economy she will show her heroine ordering a length of rope long enough to hang herself, “staring straight in front of her like Boadicea” while the hero attempts to distract her from her apparently suicidal intention by telling a wild story of his own about the naming of his dog Raoul:

“After the Vicomte de Bragelonne,” panted Richard. “He was the son of Athos, you remember. He was jilted by Louise de la Vallière.”

“And has Raoul been jilted?” gasped Julia, much interested.

Show things she certainly does, while leaping from scene to scene with astonishing fluidity, garnishing the forward pace of the action with extravagant detail and often extraordinary dialogue, and evidently with no thought of restricting her self to the basic two necessary elements.

Describing one piece of early work she wrote:

“‘This is too improbable,’ an editor once said to me. ‘I like this story but it is just too hard to swallow.’ He was talking about the only story I ever wrote, flat, from real life, and it taught me a useful lesson about the risks of using unvarnished experience.”

This must have been a turning point, as demonstrated by the wealth of wild improbabilities displayed in most of Joan’s fiction from that time onward. Undaunted by years of struggle and relishing her hard-earned early success, selling these stories for twenty-five pounds a time, after many late night hours of honing, crafting, and rewriting, she certainly earned her reputation as a storyteller of wonderful skill.

Joan concludes:

“I suppose these lessons are the writer’s next best reward after the act of writing itself, because they fill one with the impetus to start on another piece of work at once, and the resolve to avoid every pitfall and do it all much better this time.”

Lizza Aiken, 2011

A Mermaid Too Many

It was always the same when George came home at the end of a voyage. As soon as the Katharina dropped anchor by the quay and the news spread through the town, Janet left whatever she was doing—today she was bathing the cat in the dish-tub—and rushed to buy the ingredients for George’s favourite supper of shrimp-and-watercress soup followed by chitterling pie. That done, and after seeing that the whole house was as clean as a pin, which it always was, she put on the dark-blue Indian silk, the earrings George had brought her from Venice, and the Japanese slippers; then she strolled through a spray of the scent he’d found in Valparaiso, which was so potent that more than a dab of it brought all the males of the town howling round Janet’s doorstep like timber wolves. Then she settled down to wait for George.

After supper they always sat on the sofa for a little, in front of the fire, and then George would get fidgety and say, “Let’s go to bed, shall we?” And Sam the cat would be shut up in the kitchen—much to his rage, for while George was at sea, Sam slept on Janet’s bed.

So it was this time. A gale was getting up, a dry gale; the little town rocked on its base, and the wind humping along the High Street made the cobbles heave, knocked the stars about in the sky, slammed windows and doors.

George swung up Harbour Lane with his duffel bag over his sh

oulder and Janet’s present under the other arm. He was hungry, and happy to be home after months of water and salt wind; his sealegs were still under him, and the narrow, walled lane pushed him from side to side like a ninepin. Next trip he was to have command of the Katharina, and he was in a hurry to tell Janet about it.

“You murdering sod!” he shouted happily at a cyclist who shot past, brakeless, down the hairpin alley. He hitched his heavy load to the left arm and went on up to Bell Cottage, pushing open the door with his knee.

“George!” Janet’s arms were round him, and he noticed with pleasure the smoothness of the Indian silk, the scent of new-washed rush matting, Sam the cat sitting clean and furious by the fire, the weight and darkness of Janet’s coiled hair, and the bowls ready on the table for shrimp-and-watercress soup.

“Lovely,” he said, burying his nose and this time getting a tang of Valparaiso along with the shrimps and the matting.

After the first embrace they held away a little and scanned each other thirstily: Janet for any cuts or bruises that needed explaining or treatment, George to remind hnnself again of her beauty, which he had never forgotten, her beauty that held the warmth and darkness of wine.

Suddenly Janet’s eyes fixed.

“What’s that?”

“That’s my present for you!” said George proudly, and he lifted it, with a bit of an effort, onto the mantelpiece: an outsize bottle containing a fullsize mermaid. At least she was a three-foot mermaid, and that’s as large as they need to come.

George tipped the bottle in lifting it, and the mermaid sank to the bottom, but she slowly righted herself, levelled, and undulated from stem to stern.