The Serial Garden: The Complete Armitage Family Stories

Joan Aiken

* * *

Small Beer Press

www.lcrw.net

Copyright ©2008 by Small Beer Press

First published in 2008, 2008

* * *

NOTICE: This work is copyrighted. It is licensed only for use by the original purchaser. Making copies of this work or distributing it to any unauthorized person by any means, including without limit email, floppy disk, file transfer, paper print out, or any other method constitutes a violation of International copyright law and subjects the violator to severe fines or imprisonment.

* * *

CONTENTS

Joan Aiken's Armitage Stories

Yes, But This Is An Armitage Story

Prelude

Yes, but Today Is Tuesday

Broomsticks and Sardines

The Frozen Cuckoo

Sweet Singeing in the Choir

The Ghostly Governess

Harriet's Birthday Present

Dragon Monday

Armitage, Armitage, Fly Away Home

Rocket Full of Pie

Doll's House to Let, Mod. Con.

Tea at Ravensburgh

The Land of Trees and Heroes

Harriet's Hairloom

The Stolen Quince Tree

The Apple of Trouble

The Serial Garden

Mrs. Nutti's Fireplace

The Looking-Glass Tree

Miss Hooting's Legacy

Kitty Snickersnee

Goblin Music

The Chinese Dragon

Don't Go Fishing on Witches’ Day

Milo's New Word

About the Author

The Armitage Family Stories

* * * *

The

Serial Garden

The Complete

Armitage Family

Stories

The Serial Garden

The Complete

Armitage Family Stories

Joan Aiken

* * * *

* * * *

with introductions by

Garth Nix

and

Joan Aiken's daughter

Lizza Aiken

Big Mouth House

Easthampton, MA

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this story are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

The Serial Garden: The Complete Armitage Family Stories copyright © 2008 by John

Sebastian Brown and Elizabeth Delano Charlaff. All rights reserved.

"Kitty Snickersnee,” “Goblin Music,” “The Chinese Dragon,” and “Don't Go Fishing on Witches’ Day” copyright © 2008 by John Sebastian Brown and Elizabeth Delano Charlaff. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1953, 1955, 1968, 1969, 1972 by Joan Aiken. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1977, 1984, 1998 by Joan Aiken Enterprises, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction by Elizabeth Delano Charlaff copyright © 2008 by Elizabeth Delano Charlaff. All rights reserved.

Introduction by Garth Nix copyright © 2008 by Garth Nix. All rights reserved.

Interior illustrations by Andi Watson copyright © 2008 by Andi Watson. All rights reserved.

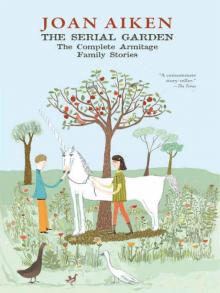

Cover art copyright © 2008 by Beth Adams (bethadams.net). All rights reserved.

Big Mouth House

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

www.bigmouthhouse.net [email protected]

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

First Edition

October 2008

Text set in Chaparral Pro. Titles set in Benjamin Franklin.

Printed on 50# Natures Natural FSC Mixed 30% post consumer recycled paper by Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aiken, Joan, 1924-2004.

The serial garden : the complete Armitage family stories / Joan Aiken ; introductions by her daughter, Lizza Aiken and Garth Nix.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Follows the adventures Mr. and Mrs. Armitage and their children, Harriet, Mark, and little Milo, as they try to find innovative ways to cope with a variety of extraordinary events including stray unicorns in the garden, lessons in magic that go awry, and eviction from their house to make way for a young magicians’ seminary.

ISBN 978-1-931520-57-7 (alk. paper)

[1. Magic—Fiction. 2. Family life—Fiction. 3. Humorous stories.] I. Aiken, Lizza. II. Nix, Garth. III. Title. IV. Title: Complete Armitage family stories. V. Title: Armitage family stories.

PZ7.A2695Se 2008

[Fic]—dc22

2008019985

Joan Aiken's Armitage Stories

* * * *

* * * *

Joan Aiken (1924-2004) began writing the Armitage Family stories when she was still in her teens and sold the first story, “Yes, but Today Is Tuesday,” to the BBC Children's Hour programme in 1944. This and another five stories about the Armitage children, Mark and Harriet, and their encounters with everyday magic, were included in her first published collection, All You've Ever Wanted, in 1953. Over the years Joan continued to add to their adventures, and the stories appeared in six further collections of fantastic tales during the next four decades. For the American collection Armitage, Armitage, Fly Away Home in 1968, Joan added a prelude introducing the Armitage parents on their honeymoon, and ensuring, by means of a wishing ring, that despite living “happily ever after” the family would never, never be bored. Before she died in 2004 she had completed four new Armitage stories, and had just sent them to her typist, together with all those from previous collections, with a letter saying that she hoped to try and have all of them gathered together and published in one volume. Here it is at last!

Joan was the daughter of writer Conrad Aiken, who was divorced from her mother, Jessie McDonald, when Joan was five. When Jessie married his friend, the writer Martin Armstrong, in 1929, the family moved from Joan's birthplace in the town of Rye to a tiny cottage in a village on the other side of Sussex. Armstrong was nearly fifty and had no children until Joan's half brother David was born in 1931, and she says: “I was rather nervous of him and he, probably rightly, found most of my remarks silly.” Nevertheless he was “immensely entertaining, both witty and erudite,” and life at the cottage was graceful in spite of the family's poverty, as Armstrong depended for their living on what he wrote. In those days there was no running water, it was drawn from a well, and no electricity, but oil lamps and fires to prepare daily. Joan always said that these formative years were lonely but happy; her friends were books.

Her brother John and sister Jane, twelve and seven years older, were sent away to school, but Jessie, who took a B.A. at McGill in her native Canada, and a Master's at Radcliffe in 1912, before marrying Conrad, was well able to teach Joan at home, and was herself a great reader. Armstrong was also an enormous influence on Joan's reading—his house was full of books—and on her writing, both by example and in his comments on her early work. All through the 1920s and 1930s Armstrong was producing novels, biographies, and poems, but perhaps his greatest gift was for short stories, and it is for his fantastic, often ghostly, and wildly imaginative stories that he will probably be best remembered. In the late 1930s the BBC invited him to write for their Children's Hour programmes, and he produced a series of stories called “Said the Cat to the Dog” about a middle-class English family and their rather extraordinary talking pets, which became an enormous success.

Joan was about sixteen and, as she says, “in a snobbish sort of teenage rebellious mood, and it seemed to me that they were terribly silly.” In fact

they probably were intentionally so, but this only reflects the difference between Joan's attitude to writing for children, and what her stepfather considered would be suitable (and indeed moral) fare for the young. “Silly” had been the most withering criticism he had levelled at her own early work, and this had clearly rankled.

"Just for fun I thought I would write a kind of skit on them, so I wrote a story, called ‘Yes, but Today Is Tuesday,’ calling my family Armitage instead of Armstrong, in which a lot of totally unexpected and horrendous things happened, sent it to the BBC, and to my amazement they took it!"

Martin Armstrong, born in 1882, public school and Cambridge educated, had served as an officer in the First World War; he was therefore not only an Edwardian, but a member of the gentry. In an English village of the 1930s there was an absolute social divide between the gentry and the villagers, and they would “meet: only on public occasions, but nevertheless they lived and worked closely together.” It seems incredible now that an “ordinary” family like the Jacksons in Armstrong's stories should of course have a “Cookie the Cook, Elsie the Maid, and Mr. Potts the Gardener” to look after them, but that they were also seen as part of the family—rather like the children of the period they would be expected to know their place and keep to it. Joan, daughter of Canadian double-graduate Jessie, must have felt as alienated as her mother in this hidebound society, and embarrassed to see it depicted in her stepfather's fiction. She describes being discouraged from playing with “the village children” who, teasing and hostile, would shout “Ginger!” at her red hair if they saw her in the road. Once when she had been reading about the Greek hero Perseus, she shouted back “I'll set Medusa on you!” She regretted it for years afterwards as she was pursued by cries of “Ooooo's Med-yoo-sa?” whenever they saw her. She does describe with great affection her relationship with Lily, the fourteen-year-old maid who helped in the house and with whom she shared stories about Mowgli and Tarzan and sometimes even movies; The Count of Monte Cristo and other films were occasionally shown in the tin-shack cinema in the small town of Petworth, five miles away, to which they had to walk. The village had one small shop, and a blacksmith. A carrier fetched supplies from Petworth with a horse and covered cart. It seems less surprising, then, that Joan's idea of an ordinary family living “happily ever after” in a delightful village should include some fairly oddly assorted characters, let alone dreadful old fairy ladies and Gorgons, as a matter of course.

From an early age, Joan had told stories to her half brother David while climbing and walking around the Sussex Downs behind the village. In the beginning these would be a string of fairly unrelated events, as, trying to spin the story out till they reached home again, she would add in a witch, a dragon, another disaster, or just the answer to the inevitable question “And then what happened?” She describes with delight the moment when she realised that she could in fact plot it all out so that it tied up satisfactorily, with the end relating to the beginning and with seeds laid along the way to bear fruit later. Despite the fact that the Armitage stories began at this time, and span a period of over fifty years, they have kept a consistent voice and retain the sense of atmosphere and period of her childhood home. While time and technology moved on and were incorporated with Aiken's usual mix of matter-of-fact and magic, the family characters remain essentially themselves, grappling with the more absurd twentieth century developments alongside the inconvenience of untimely curses and irritable local witches. Thanks to an extraordinarily wide range of reading in her early years, and her belief in the benefits of a powerful imagination, Joan was prepared for almost anything. Brought up on a diet of Dickens, Dumas, Austen, and the Brontës, Kipling, Stevenson, Nesbitt, Trollope, Scott, Victor Hugo, and many, many more, she was equipped, like the hero of a myth, with the tools, or, in her case, the imaginative power, to meet any contingency, and she was going to need it.

The Armitage stories in fact begin during the Second World War, when, having been sent to board at a small school in Oxford, Joan was unable to return home. When the school was forced to close down, she took what turned out to be an appallingly dull job ruling lines on cards for the BBC in an evacuated office in the middle of nowhere, as London was being bombed. Aiken's “The Fastness of Light” in the collection A Creepy Company describes this period fairly vividly, and “Albert's Cap” in Michael Morpurgo's anthology War describes London in the Blitz, but these are rare examples of her using material directly from her life. Although there are oblique references to wartime difficulties, for example the requisitioning of the Armitage house in “The Frozen Cuckoo,” or her brother David's enthusiasm for planes during National Service with the R.A.F. in “Dragon Monday,” it was her fantasy that sustained her during these bleak years. In fact the next fifteen years were to be almost impossibly difficult as she dealt with war, work, marriage, motherhood, and then becoming widowed, homeless, and insolvent all in quick succession. What did she do? She wrote, and by 1955 she had published her second fantasy collection, More Than You Bargained For, including four more Armitage stories. Although these might have to be written on trains, while feeding chickens, or, as she said, while peeling potatoes with the other hand, she described how they always came almost out of the blue, in a terrific and wonderful urge to get themselves written.

By 1960, she was at last settled in a house of her own, back in Petworth, and was able to plan and write full-length novels; she produced eight in quick succession. The Armitage stories, when they appeared again over ten years later, revisited happier memories from the village, adventures with her cousin Michael on holidays from Northumberland, the exploits of her older scientist brother and much admired older sister on their visits home, actual events like the lady gardener who tried to buy the quince tree, and finally, in “Milo's New Word,” the arrival of David the baby brother and the delight of having a smaller creature to care for. Written long after the death of her mother, Jessie, this has some of the most tender descriptions of “Mrs. Armitage,” perhaps to make up for a previous and uncharacteristically drastic piece of writing. In The Way to Write for Children, Joan writes about the degree of tragedy permissible in a work for children:

Children have tough moral fibre. They can surmount sadness and misfortune in fiction, especially if it is on a grand scale. And a fictional treatment may help inoculate them against the real thing. But let it not be total tragedy. Your ending must show some hope for the future.

One Armitage story stands out as unforgettable for many readers, and clearly Joan, too, felt she had to return to “The Serial Garden” and offer some hope of a happier ending, not just to poor Mr. Johansen and his lost princess, but perhaps also to those who, after reading the description of the appalling but unwitting destruction wreaked by Mrs. Armitage, are still reeling with shock that this kind of thing can indeed happen. Mr. Johansen reappears here in two more stories, and although clearly what was done cannot be undone, hope is offered for a solution. It was Joan's suggestion that this collection be called The Serial Garden, perhaps wishing to alert those readers who were still waiting for the promised “happily ever after” that she had not forgotten them.

Lizza Aiken, 2008

[Back to Table of Contents]

Yes, But This Is An Armitage Story

* * * *

* * * *

I used to wish for an Armitage Monday, a day when unicorns would overrun the garden, or I would be enlisted for aerial combat against a dragon, or that every potato in the house would turn into a beautiful Venetian glass apple. I also hoped that if these things did happen, my parents would accept it as a natural consequence of Mondays, and if they were turned into beetles they would just get on with their lives. I, of course, would ensure that everything would come out all right by the end of the day.

These marvelous Mondays never did happen for me, except in my imagination. Nor did I ever calm a storm with a model weather ship, or make a magical garden out of cardboard pieces from a breakfast cereal box. But I could feel as

if I did have these experiences, because I read about all these things and more as they happened to Harriet and Mark Armitage in the wonderful stories by Joan Aiken, collected here all together for the very first time. In fact, some of the stories have never been published before, and when I was sent them to read, I felt like I'd won the lottery, and a prize far better than mere money. A new Armitage family story is worth more than rubies to me, or even a gold piece combed from a unicorn's tail.

I have often returned to Joan Aiken's books and stories over the years, enjoying them again and again. I have a particular fondness for her novels Black Hearts in Battersea, The Cuckoo Tree, and Midnight is a Place. But of all her work, I think it is her short stories I love the most, and foremost among her short fiction it is the tales of the Armitage family that are closest to my heart.

Before writing this introduction I never paused to wonder why I love these stories; I just ate them up, so to speak, and wanted more and wanted to repeat the experience.

Reflecting on why these stories appeal to me so much, I think it is because they so skillfully blend a relatively normal 1950-ish English childhood with the fantastic, and Aiken makes the fantastic an everyday thing while still retaining its mysterious and mythological power.

It is very difficult to mix everyday life and the things of myth into a story. Often you end up making the myths ordinary and the ordinary stuff even duller than it was already. Aiken manages to do it without a false note, and creates a world—an Armitage world—that feels true and is a delight to visit.

But as I never needed to know this before, you don't need to know it now. It is enough that these are great stories. If you start to read one, you won't be able to stop, and now here is this wonderful volume that means you won't have to stop, but can visit the Armitages again and again.

But be careful if you're reading on a Monday....

Garth Nix, 2008