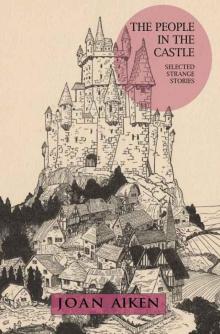

The People in the Castle: Selected Strange Stories

Joan Aiken

Table of Contents

Introduction by Kelly Link

The Power of Storytelling: Joan Aiken’s Strange Stories

A Leg Full of Rubies

A Portable Elephant

A Room Full of Leaves

Furry Night

Hope

Humblepuppy

Listening

Lob’s Girl

Old Fillikin

She Was Afraid of Upstairs

Some Music for the Wicked Countess

Sonata for Harp and Bicycle

The Cold Flame

The Dark Streets of Kimball’s Green

The Lame King

The Last Specimen

The Man Who Had Seen the Rope Trick

The Mysterious Barricades

The People in the Castle

Watkyn, Comma

Publication History

About the Author

Read More Joan Aiken collections from Small Beer Press: The Serial Garden

Read More Joan Aiken collections from Small Beer Press: The Monkey’s Wedding

Small Beer Press

Short Story Collections by Joan Aiken

All You’ve Ever Wanted

More Than You Bargained For

A Necklace of Raindrops

A Small Pinch of Weather

The Windscreen Weepers

Smoke from Cromwell’s Time

The Green Flash

A Harp of Fishbones

Not What You Expected

A Bundle of Nerves

The Faithless Lollybird

The Far Forests

A Touch of Chill

A Whisper in the Night

Up the Chimney Down

A Goose on Your Grave

A Foot in the Grave

Give Yourself a Fright

Shadows and Moonshine

A Fit of Shivers

The Winter Sleepwalker

A Creepy Company

A Handful of Gold

Moon Cake

Ghostly Beasts

The Snow Horse

The Serial Garden: The Complete Armitage Family Stories

The Monkey’s Wedding

THE PEOPLE

IN THE

CASTLE

SELECTED

STRANGE

STORIES

JOAN AIKEN

Small Beer Press

Easthampton, MA

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

The People in the Castle: Selected Strange Stories copyright © 2016 by Elizabeth Delano Charlaff

(joanaiken.com). All rights reserved. Page 254 of the print edition is an extension of the copyright page.

Small Beer Press

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

smallbeerpress.com

weightlessbooks.com

[email protected]

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aiken, Joan, 1924-2004, author. | Aiken, Lizza, writer of

introduction. | Link, Kelly, writer of introduction.

Title: The people in the castle : selected strange stories / Joan Aiken ;

introduction by Lizza Aiken and Kelly Link.

Description: First edition. | Easthampton, MA : Small Beer Press, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050134 (print) | LCCN 2016007991 (ebook) | ISBN

9781618731128 (hardback) | ISBN 9781618731135

Subjects: | BISAC: FICTION / Short Stories (single author). | FICTION /

Fantasy / Short Stories. | FICTION / Literary. | FICTION / Fairy Tales,

Folk Tales, Legends & Mythology.

Classification: LCC PR6051.I35 A6 2016 (print) | LCC PR6051.I35 (ebook) | DDC

823/.914--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050134

First edition 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Set in Centaur 12 pt.

Cover art “The Castle in the Air” by Joan Aikman, 1939. © Blue Lantern Studio/Corbis.

Paper edition printed on 50# Natures Natural 30% PCR recycled paper by the Maple Press in York, PA.

Introduction by Kelly Link

In 1924, Joan Aiken was born in a haunted house on Mermaid Street in Rye, England. Her father was the poet Conrad Aiken, perhaps most famous now for his short story “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” and her mother was Jessie MacDonald, who homeschooled Joan and filled her earliest years with Pinocchio, the Brontës, and the stories of Walter de la Mare, and much more. (Her stepfather Martin Armstrong was, as well, a poet; Joan Aiken’s sister and brother, Jane Aiken Hodge and John Aiken, like Joan, became writers.) Aiken wrote her first novel at the age of sixteen (more about that later) and sold her first story to the BBC around the same time. In the fifties and sixties, she worked on the short story magazine Argosy and from 1964 on, she wrote two books a year or more, roughly one hundred in all. She wrote gothics, mysteries, children’s novels, Jane Austen pastiches, and an excellent book for would-be authors, The Way to Write for Children. Her first book was the collection All You’ve Ever Wanted and Other Stories, followed by a second book of short stories More Than You Bargained For—stories from these collections were published in a kind of omnibus in the U.S., Not What You Expected, which was the first book by Aiken that I ever read. Her series of alternate history novels for children, a Dickensian sequence that starts with The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, has stayed in print, I believe, almost continuously since she began writing it, although I still remember being told by her agent, Charles Schlessiger, that when he delivered The Wolves of Willoughby Chase to her publisher, her editor asked if Aiken would consider sending them another collection instead. (Well: the world is a different place now.) The “Wolves” sequence is bursting to the seams with exiled royalty, sinister governesses, spies, a goose boy, and plucky orphans—and, of course, the eponymous wolves. The Telegraph said of Aiken that “her prose style drew heavily on fairy tales and oral traditions in which plots are fast-moving and horror is matter-of-fact but never grotesque.”

Many many years ago, I had a part-time job at a children’s bookstore, which mostly—and happily—entailed reading the stock that we carried so we could make recommendations to adults who came in looking to buy books for their children. (Our customers were almost never children.) I reread the still ongoing “Wolves” novels and then began to track down the Aiken collections that I had checked out of the Coral Gables library to read as a child—collections whose titles still enticed: The Far Forests, The Faithless Lollybird, A Harp of Fishbones. When, eventually, I moved to Boston, I got a job at another bookstore, this one a secondhand shop on Newbury Street—in part so that I had a firsthand shot at hunting down out-of-print books for myself. I can still remember the moment at which, standing at the top of a platform ladder on wheels to reach the uppermost shelf to find something for a customer, I found Joan Aiken’s first novel The Kingdom and the Cave as if it had only just appeared there (which it probably had. The Avenue Victor Hugo Bookshop’s owner, Vincent McCaffrey, bought dozens of books each day).

And now, of course, it’s quite possible to find almost any book that you might want online. (The world is a diff

erent place now.)

I recently spent a long weekend in Key West at a literary festival where the organizing theme was short stories. How delightful for me! There was much discussion on panels of the challenges that short stories present to their readers. The general feeling was that short stories could be difficult because their subject matter was so often grim; tragic. A novel you had time to settle into—novels wanted you to like them, it was agreed, whereas short stories were like Tuesday’s child, full of woe, and required a certain kind of moral fortitude to properly digest. And yet it has always seemed to me that short stories have a kind of wild delight to them even when their subject is grim. They come at you in a rush and spin you about in an unsettling way and then go rushing off again. There is a kind of joy in the speed and compression necessary to make something very large happen in a small space. In contemporary short fiction, sometimes it’s the language of the story that transmits the live-wire shock. Sometimes the structure of the story itself—the container—the way it unfolds—is the thing that startles or energizes or joyfully dislodges the reader. But: it does sometimes seem to me that for maybe the last quarter of the previous century, the subject matter of literary short fiction was somewhat sedate: marriage, affairs, the loss of love, personal tragedies, moments of self-realization. The weird and the gothic and the fanciful mostly existed in pockets of genre (science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery, children’s literature) as if literature were a series of walled gardens and not all the same forest. We had almost nothing in the vein of Joan Aiken’s short stories, which practically spill over with mythological creatures and strange incident and mordant humor. And yet at the time when she began to write them, in the 1950s, when Aiken was an editor at Argosy as well as a featured author, there were any number of popular fiction magazines publishing writers like John Collier, O’Henry, Elizabeth Bowen, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl. Magazines have smaller circulations now; there are fewer magazines with circulations quite so broad; and yet there are, once again, many established and critically acclaimed—as well as new and startlingly brilliant—writers working in the fantastic mode. The jolt that this kind of writing gives its reader is the pleasure of the unreal in the real; the joyful, collaborative effort that imagining an impossible thing requires of such a story’s reader as well as its writer. It seems the right moment to introduce the stories of Joan Aiken to a new audience.

The particular joys of a Joan Aiken story have always been her capacity for this kind of brisk invention; her ear for dialect; her characters and their idiosyncrasies. Among the stories collected in this omnibus, are some of the very first Joan Aiken stories that I ever fell in love with, starting with the title story “The People in the Castle,” which is a variation on the classic tales of fairy wives. “The Cold Flame” is a ghost story as is, I suppose, “Humblepuppy,” but one involves a volcano, a poet, and a magic-wielding, rather Freudian mother—while the other is likely to make some readers cry. In order to put together this omnibus, we went through every single one of Aiken’s collections, talked over our choices with her daughter Lizza, reworked the table of contents, and then I sat down and over the course of six months, typed out every single one. I’m sorry that we couldn’t include more—for example, two childhood favorites, “More Than You Bargained For” and “A Harp of Fishbones,” but there was a great pleasure in reading and then rereading and then transcribing stories like “Hope” in which a harp teacher goes down the wrong alley and encounters the devil. And “A Leg Full of Rubies” may be, in its wealth of invention, the quintessential Joan Aiken short story: a man named Theseus O’Brien comes into a small town with an owl on his shoulder, and unwillingly inherits a veterinary practice, a collection of caged birds including a malignant phoenix, and a prosthetic leg full of rubies which is being used to hold up the corner of a table. Joan Aiken is the heir of writers like Saki, Guy de Maupassant and all the masters of the ghost story—M. R. James, E. F. Benson, Marjorie Bowen—I can’t help but imagine that some readers will encounter these stories and come away with the desire to write stories as wild and astonishing and fertile as these.

In 2002, the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts invited Joan Aiken to be its guest. I went in order to hear her speak. She was so small that when it was time for her to give her lecture, she could not be seen over the podium—and so finally someone went and found a phone book and she stood on that. She talked about how her stepfather, Martin Armstrong, had been impatient in the morning at the breakfast table when the children wanted to tell their dreams. Other people’s dreams are, he said, boring. And then Joan Aiken proceeded, in her lecture, to tell the audience about a city that she visited in a series of recurring dreams. She said that it was not a city that existed in the real world, but that after walking its streets for so many years in dreams, she knew it as well as she knew London or New York. In this city, she said, was everyone she had ever loved, both the living and the dead. We all listened, riveted. Did she talk about anything else? I don’t remember. All I recall is her dream and the telephone book.

The Power of Storytelling: Joan Aiken’s Strange Stories

Joan Aiken once described a moment during a talk she was giving at a conference, when to illustrate a point she began to tell a story. At that moment, she said, the quality of attention in the room subtly changed. The audience, as if hypnotised, seemed to fall under her control.

“Everyone was listening, to hear what was going to happen next.”

From her own experience, whether as an addictive reader from early childhood or as a storyteller herself, learning to amuse a younger brother growing up in a remote village, by the time she was writing for a living to support her family, she had learned a great respect for the power of stories.

Like a sorcerer addressing her apprentice, in her heartfelt guide, The Way to Write for Children, she advises careful use of the storyteller’s power:

“From the beginning of the human race stories have been used—by priests, by bards, by medicine men—as magic instruments of healing, of teaching, as a means of helping people come to terms with the fact that they continually have to face insoluble problems and unbearable realities.”

Clearly this informed her desire to bring to her own stories as much richness, as many layers of meaning, and as much of herself, her extensive reading, and her own experience of life as she possibly could. Stories, she said, give us a sense of our own inner existence and the archetypal links that connect us to the past . . . they show us patterns that extend beyond ordinary reality.

Although she repudiated the idea that her writing contained any overt moral, nevertheless many of Joan Aiken’s stories do convey a powerful sense of the fine line between good and evil. She habitually made use of the traditional conventions of folk tales and myths, in which right is rewarded and any kind of inhumanity gets its just deserts. Her particular gift, though, was to transfer these myths into richly detailed everyday settings that we would recognise, and then add a dash of magic; a doctor holds his surgery in a haunted castle, and so a ghost comes to be healed.

What Aiken brings to her stories is her own voice—and the assurance that these stories are for you. By reading them, taking part in them, not unlike the beleaguered protagonists she portrays as her heroes—struggling doctors, impatient teachers or lonely children—you too can learn to take charge of your own experience. It is possible, she seems to say, that just around the corner is an alternative version of the day to day, and by choosing to unloose your imagination and share some of her leaps into fantasy you may find—as the titles of some of her early story collections put it—More than You Bargained For and almost certainly Not What You Expected . . .

One of the most poignant, hopeful, and uplifting stories in this collection—and hope, Aiken believed, was the most transforming force—is “Watkyn, Comma.” Here she uses the idea of a comma—in itself almost a metaphor for a short story—to express a sudd

en opening up of experience: “a pause, a break between two thoughts, when you take breath, reconsider . . .” and can seize the opportunity to discover something hitherto unimaginable.

In the course of one short story our expectations are confounded by the surprising ability with which Aiken generously endows her central character—to see something we would not have expected. By gently offering the possibility of previously unknown forces—our ability to develop new capacities, the will for empathy between the many creatures of our universe, our real will to learn to communicate—she leaves us feeling like the characters in the story—“brought forward.”

Aiken draws us into a moment of listening—gives an example of how a story works its magic—and invites us to join in the process of creative sharing, believing, asking:

“Could I do this?”

And hearing her answer:

“Oh, never doubt it.”

Aiken is perfectly capable of showing the dark side of the coin, of sharing our dangerous propensity to give in to nightmares and conjure monsters from the deep, but at her best and most powerful she allows her protagonists to summon their deepest strengths to confront their devils. In the story of this name, born from one of her own nightmares, even Old Nick is frustrated by a feline familiar called Hope.

This collection of stories, taken from her entire writing career, some of which I have known and been told since I was born, form a magical medicine chest of remedies for all kinds of human trials, and every form of unhappiness. The remedies are hope, generosity, empathy, humour, imagination, love, memory, dreams . . . Yes, sometimes she shows that it takes courage to face down the more hair-raising fantasies, and conquer our unworthy instincts, but in the end the reward is in the possibility of transformation. The Fairy Godmother is within us all.