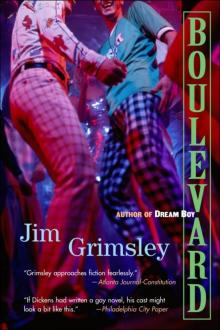

Boulevard

Jim Grimsley

JIM GRIMSLEY

Boulevard

A NOVEL

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

For Madeleine St. Romain

For if they do these things in a green tree,

what shall be done in the dry?

Luke 23:31

Contents

THE PORNOGRAPHER

THE GREEN TREE

LOUISIANA PURCHASE

PLEASURE FOR PAIN

REASON TO LIVE

The Pornographer

Newell took his duffel down from the baggage rack, slung the strap over his shoulder, and climbed off the bus onto the pavement. A breathless feeling, that first step into the open air. Stowing the bag in a coinoperated locker, he pocketed the key and unfolded the map of the city he had bought by special order from Ed White’s filling station in Pastel. The closest street sign read Tulane Avenue, and he found it on the map, the fact giving him a rush of happiness, to know the name of the street, to understand where it ran in relation to all the rest. He took one step away from the bus station, then another. He was walking along Tulane Avenue in the city of New Orleans.

That morning the city was new to him, and he could hardly imagine himself standing among such huge buildings as these, on streets with names like Carondelet, Gravier, Poydras, Magazine, St. Charles, words that ran through his head like notes of music. He guided himself through a tangle of streets and slivers of buildings, after only a couple of wrong turns, to Canal Street, where he took in the width of the thoroughfare—so many lanes for cars going each way, and more lanes down the middle, where city buses were running. He walked past shops, closed at this early hour, places to buy clothes, drugstores, fast food restaurants. Here was New Orleans early in the morning, hardly awake yet, but already it was like nothing he had ever seen.

The street he wanted lay on the other side of Canal, and he had said the name in his head a hundred times in the last few days, Bourbon Street, a place he had heard about from Flora and Jesse, who had come here twice for the Mardi Gras. If his dream came true today he would live on Bourbon Street, somewhere on it; and if that failed he would find some other place in the French Quarter, because he wanted that more than anything, not simply to live in the city but to live in the center of it. So he turned onto Bourbon Street from Canal, on the side of the street occupied by the wall of a store called Maison Blanche, beyond which, even at that hour, a fair number of people were walking around, some of them with the look that maybe they had been here since the night before.

He would get accustomed to this smell of vomit and piss, he thought, as he headed down the tilted sidewalks. Tired workers in uniforms were taking up street barricades, and traffic moved sluggishly along the cross streets. The buildings were low, decorated with ironwork, wooden doors sagging, stucco flaking and falling off; restaurants, Takee-Outee stands selling egg rolls, bars, more bars, places to buy nightgowns and underwear in multiple colors, more bars, with patios and balconies, bars where you could watch women strip off their clothes, and farther down, places where you could watch men and women. A marquee showed black-and-white glossy pictures of the strippers, Tammy and Nanette and Roberto, names he remembered for a moment, then forgot.

He walked a long way before he found a newspaper box, fumbled with the quarter before slipping it in the slot. The newspaper was called the Times-Picayune, and his copy was printed on green paper, a fact that so distressed him he rolled up the paper and hurried away from the vending box without reading the headlines. But at the next box he saw all those papers were green too, so he supposed it was all right.

On his map, in the center of the French Quarter on the river side, he had marked a place called Jackson Square, and now he headed toward it down St. Peter Street. He had only a vague notion of what a square might be but emerged from the street in front of a big gray church. Mist hung over the stone plaza in front of him, the stones covered with pigeons looking for something to eat, and he walked into the crowd of feathers and cooing, headed toward one of the iron benches in front of the church. He sat on the bench and looked around. The square was a big open space, but the buildings looked like nothing he had ever seen before, the church rising up gray and austere, stone buildings flanking it, proper and harmonious, with historical plaques about the builders and the history. Behind him, facing the church, lay a green park enclosed in an iron fence. The park gates stood open at the moment, but there was a sign giving the hours of business. He sat in the mist with the green newspaper in his lap and flocks of pigeons at his feet, the air so wet he could feel the moisture on his skin, the gray of the mist muting everything. A sound cut through the morning, a long lowing, and he understood it was a ship’s horn he was hearing because he had heard a ship’s horn on television before, but the real sound raised the hackles on his neck, the horn blew on and on. He could tell the sound was coming from behind him. That would be the river, he thought, and he started to walk toward it, because he knew what river it was.

He would learn the names: Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo, the Pontalba buildings, the Moonwalk, Jax Brewery, the French Market, Café du Monde, all these mysteries would be explained to him in time, but this was his first walk to the river, and once he stood on the levee, one could understand that the sight might move him, because it was the Mississippi, and this bend of the river had created the city behind him. He could feel the power of it, the river flowing past him, gray and sooty, wind lifting over the water, a white ship passing upriver with a tug for an escort, a seagull riding the breeze near the wharf. He stood there for a long time, looking at all of it, taking it in. After a spell of that, he sat on one of the benches along the Moonwalk, opened the paper, and started to read.

Skipping over the article about President Ford and the First Lady at Camp David, skipping over the article about Richard Nixon planting flowers in the garden at San Clemente, Newell searched for the classified ads about rooms for rent in the French Quarter. There were listings for Metairie and Elysian Fields and Gretna, but these were all for houses or apartments, and besides, he had no idea where any of those places might be. The rented room list was actually quite short, and he studied it closely, spreading out his map as best he could in the breeze off the river. Not a single room on Bourbon Street. But some of the addresses were close, according to his map, which had a special section on the French Quarter. He found rooms on St. Ann, Governor Nicholls, and Ramparts, and more across Ramparts and Esplanade, outside the French Quarter but close by. Was he ready? He folded the map and was heading for the first place, on St. Ann, until he remembered it was early, hardly anybody would be ready to rent a room at such an hour. So he tucked the map into his pocket and folded the newspaper section by section.

He sat with the river flowing past him, studying the tiny houses on the distant shore, reminding himself that this was the Mississippi River, that he was sitting in New Orleans, and this seemed to him a great accomplishment. Never mind the worry that now he had to find a room to rent, a place to stay. That he had to find a job and go to work. Never mind any of that, at this moment he could do nothing more than watch the river.

But he was hungry after the trip and decided he ought to eat something, so after a while he left the Moonwalk and retreated across the levee to the Café du Monde, where a lot of people were sitting and eating off little plates and drinking coffee. Since there were so many people and so many round white metal tables outside, he sat in a chair, and pretty quickly a girl about his own age rushed up to him to ask what he wanted. It turned out all the Café du Monde sold was coffee and doughnuts, except that the doughnuts were called something else, a word the waitress said three times, bay-nyays, with Newell simply looking at her, at which point she said, “They’re doughnuts with powdered sugar on them. And café au lait

.” She hurried off to take somebody else’s order, and finally he saw the word she was talking about, beignets, on a sign in one of the windows, and he took a deep breath. What he had really wanted was some fried eggs, but he would gladly eat the doughnuts instead. The city was already showing itself to be a complicated place. A restaurant that served nothing but doughnuts, full of people, laughing and chattering.

The doughnuts were hot and sweet, but he kept blowing the powdered sugar up his nose, at first. He got one order and another, and paid for each out of the bills in his pocket. He knew you were supposed to tip a waitress like this, but he could only guess how much, so he laid a quarter on the table and added a nickel as an afterthought. The coffee, which was what café au lait turned out to be, had a rich cream in it and ran smooth as silk down his throat. He hardly ever drank coffee, but he thought he might like this kind, after a while. His stomach felt better with something in it.

For an hour or so he walked, at first in a place called the French Market, where a lot of produce vendors had already opened for business, and later along Esplanade, a wide avenue darkened with trees, with a green median running down the center, which anyone who lived in New Orleans would have known to call a neutral ground. Newell crossed onto it and walked down it, among the trees and plantings, with traffic on both sides of him.

Newell arrived at the address on St. Ann by a roundabout route, and stood patiently at the door waiting for someone to answer. The woman who came to the door was well dressed and carried a tiny dog in the crook of her arm, and when she quoted the price of the rooms, the dog silently licked her wrist. Newell thanked her for her trouble and went away, because she was asking way too much money for a room, and he didn’t mind letting her know that. He walked to the place on Governor Nicholls, for which the price of the rent was listed in the paper, three hundred dollars a month, and the room turned out to be in the back of a service station across Ramparts from the Quarter. The room had only one tiny window, high up in the wall. The bathroom consisted of a toilet and sink and no shower or bathtub. A sweet, balding man in a sleeveless T-shirt was showing the room, and Newell looked for a polite moment or two, and then said he had some other places to see but might be back.

He walked from place to place, to all the listings in the newspaper, and found nothing under three hundred dollars a month, which was more than he could pay with no more money than he had. Jesse had told him to stay at the YMCA, which he could rent by the night, till he found a job, but Newell had balked at that suggestion. But he might need to stay there tonight, he thought, and by then he was hungry again, so he found a place to buy a sandwich, a roast beef po’ boy that dripped gravy and mayonnaise onto the wax paper in which it was wrapped. He wanted to ask for a phone book, but the people in the sandwich shop were too busy, so he finished his sandwich and wandered for a while.

He visited a few of the shops in the lower Quarter, pretending to browse like a real customer, a store full of used books, including some books by Robert Heinlein and Poul Anderson for a quarter apiece, a store full of old postcards and glassware, stores full of Mardi Gras masks and costumes, places such as he had never imagined, though he kept a poker face and acted as if he had seen it all before. He ambled along Barracks, nearing Decatur Street, when he walked into a shop near the corner, which turned out to be a junk shop, tables and shelves of junk everywhere you looked, and the ceilings must have been twenty feet at least, wall-papered with dark paper that had stained even darker with age. A sign had been lettered onto the front window by a careful hand, and the sign, in contrast to the building, was bright and well kept. “Hendeman’s Rare and Used,” the sign read, but what? Everything, apparently, including old ashtrays, a wooden baby carriage near collapse, several wooden buckets, jars of beads, masks hung on the walls and piled on the shelves. Across the room behind a counter a woman was watching him. She had broad shoulders and hips and a narrow waist, and was dressed in a light, flowered dress with a buff-colored sweater wrapped around her. A large cat prowled the counter near her elbow, fluffing against her hand, till finally she shoved it away in irritation.

She was as handsome as a man, he thought, when he was close enough to see her face. Square-faced, high cheekbones, a strong jaw, full flaring lips, heavy eyebrows, her hair done up in a loose bun. “Are you looking for something?” she asked in a pleasant, husky voice.

“Do you have a phone book?”

She lifted a white-covered directory to the counter and set it in front of him. “Do you want the phone?”

“No ma’am. I just need to look up the address of the YMCA.”

“Well, that’s on Lee Circle,” she said, “I can tell you that.”

“Lee Circle?”

“Yes. You take the streetcar uptown, and you get off at Lee Circle.”

“How do I know it’s Lee Circle?”

“Because it’s a circle,” she said, “and you know who Lee is, don’t you? Robert E. Lee.”

“Oh.” He was distracted, opening his map to see if he could find the place.

She found his map to be amusing, he could see by her smile. She had some papers she was looking at, and she went back to doing that, correcting something with a pencil. After a while she asked, “You’re looking for a place to stay?”

“Yes ma’am. I been looking all day. All the ads in the paper.”

She smiled at him, started to say something, changed her mind. Then changed her mind again. “Most people in the Quarter don’t put an ad in the paper if they have a room to rent.”

“Why not?”

“Because they don’t have to. And anyway, they would be afraid of tourists. Or out-of-town people. Most people from the Quarter would put out the word to their friends they had a room, and wait.”

“Well, there’s ads in this paper for rooms,” Newell fanned the paper up and down, “but there’s not a single place that’s fit to live in.”

She shrugged. “The YMCA is nice. You won’t mind it.”

“I know.”

After another moment, she walked into her office, a door behind some filing cabinets, and he figured she was tired of talking. He looked up “YMCA” anyway and wrote the number on a scrap of paper. He closed the phone book and laid it down, and as he turned away her voice stopped him. “Do you have a job?” She had put on a pair of glasses and had a ledger in her hand. She set the ledger on the counter and opened it to a page and started to make entries in it.

“No ma’am. Not yet.”

“Most people aren’t going to rent you a room if you don’t have a job.”

“I can get a job. It looks like there’s a lot of restaurants and places around here. I can do something. I worked in a grocery store in Pastel. And I graduated from high school.”

She wanted to smile, he could tell, and he supposed he had said something foolish. “Well, I’m sure you’ll be fine,” she said.

He headed for the door without thanking her, thinking she was making fun of him, but again her voice stopped him. She was looking at him with her hand on the cat’s back, smoothing its fur.

“I have a room, upstairs.”

He stopped and turned. There were no stairs anywhere in the room.

“Would you like to see it?”

He nodded.

She sighed and closed the ledger. Unlocking a drawer, she pulled out a ring of keys and put them in her pocket. She led him outside to the street, then unlocked a narrow door next to the store. This door, which looked like a tall piece of fencing, opened to a narrow passageway that led to the interior of the block. He followed her to a courtyard full of green, the sound of water running somewhere; he could see a fountain through a pair of archways, to the right of which rose stairs, and she led him up those to a narrow doorway. She gestured to another door down the gallery from the one she was unlocking, “There’s an apartment there, somebody’s living in it. This next one is the room that’s empty.”

The room was tall and narrow, with a single casement window at the front, an

d a set of narrow French doors leading to the balcony that ran along the front of the building. A ceiling fan hung from the ceiling, and when she flicked a switch on the wall it began to turn slowly. At the back of the room, behind a white door, stood a bathroom with a bathtub, a sink, and a toilet. High up in one wall of the bathroom was a window, admitting dingy light. The two rooms seemed dark to him, but the main room was clean and big enough, with a bed in it, and a wooden wardrobe, a chair, a small table, and a small refrigerator with a lamp on top of it.

“The last fellow who lived here skipped out on the rent,” she said. “He had owed me for two months. And he had a job.”

“It’s a nice room,” Newell said.

“My husband used it for an office, when he was an astrologer.”

Newell had no idea what to say. He wandered in the room and felt the money in his pocket and wished. When he turned around, she was watching him.

“If you can pay me two months rent in cash right now, I’ll let you move in,” she said.

“How much is that?”

“Two hundred fifty dollars a month. That’s five hundred dollars.”

This was nearly all he had. But he pulled the money out of his pocket at once and counted five hundred dollars into her hand.

“You pay me the rent in cash on the first of the month, beginning with July,” she said. “I keep this second month’s rent in case you skip out. You can have these last few days of May for nothing.”

He had less than a hundred dollars left. In a month he would have to give her two hundred fifty dollars more. If he didn’t, she would keep his extra two-fifty and kick him out in the street. Looking at her, he had no doubt she would do exactly that. The thought left his mouth dry. But he nodded and said, “That’s fine.”

“Come downstairs and show me some I.D.”