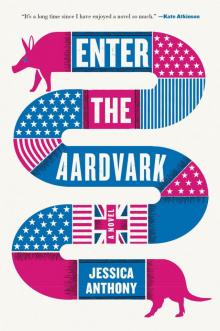

Enter the Aardvark

Jessica Anthony

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2020 by Jessica Anthony

Cover design by Gregg Kulick

Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

twitter.com/littlebrown

First ebook edition: March 2020

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Title page illustration by Louis Jones

ISBN 978-0-316-53613-4

E3-20200302-DA-NF-ORI

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter

1.

2.

3.

Months Later

Acknowledgments

Discover More

About the Author

To Thomas Shearman Anthony

and Susan Terrell Anthony

One of the inevitablest private miseries is this multitudinous efflux of oratory and psalmody from the universal human throat; drowning for the moment all reflection whatsoever, except the sorrowful one that you are fallen in an evil, heavy-laden, long-eared age, and must resignedly bear your part in the same.

—Thomas Carlyle, 1850

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

—a whirling mass of vapors is unhinged, shooting through outer space for an infinity until it collides with an ellipsis which does not let go, and after another infinity, the vapors boil into fire clouds, trapped by gravity, turning and returning until the boiling clouds, accepting fate, cool into a single mantle which cracks open in places, and here comes the lava, expanding, but there are also places where the expanding lava cannot escape and so it (the lava) pushes itself against itself and ta-da: mountains, new vapor rises up through the surface of the mantle, hitting the air, and it is all at once water, big water, and this big water hits the hot lava, steam shoots up, pluming, and it’s these watery plumes rising and falling ad nauseam that birth the oceans, and within the oceans are vast trenches paralleled by islands, which are cool rock formations from the hot lava varietals sludging obscenely over the mantle, itself now a whole globe of unmappable graywacke and chert, and the sun shines upon these waters until, in the shallowest banks, atolls and shelves, tumbling in the warm current, here come the flagellates, the plankton and phytoplankton, all tense, innumerous, ticking and rolling the floor-bottom, which is coated in algae and lampshells and pouchy glass sponges until here come the copepods, krill and medusae, the crab larvae, the pteropods, salps and heteropods, and the worms—my god, the arrow worms, something must be done about the freaking arrow worms—so enter the squirrelfish, enter the mantis shrimp, the flat/lantern/hatchet fish, enter the miniature squid, and some grow tails, and all have shells and mouths, they swallow everything, fattening into fish, and these plumpy fish grow long, swimmy, they shake the oceans into a state, and some of these fish hanging out at the edges of some of these pools are bumping their snouts into the earth, they want to dry off, go upland, and Lo, here begins the Great Creep, and will you look at them there ectothermic tetrapod vertebrates go!

All hail the Devonian nerds! The tiktaaliks and tulerpetons tossing back their flat heads, fuffing oxygen up through their watery tubes, eventually shedding their gills for skin, for open air, and still another infinity must pass as these miserable vertebrates scha-lump around the shifting plates until they at last settle the Karoo beds of southern Africa as bent-legged, flared-elbowed reptilians all mastering the art of double articulation, their planes of movement align, they hasten toward quickening until in their skulls a second bony palate is formed, foreshadowing the near-complete separation of food, of air, these therapsid temporal openings are migrating toward the top of the skull, and here’s the sagittal crest, the brain case and rostrum, they are the virgin class Mammalia, within which not long after emerges a clade of afrotherian mini-beasts, litters of sengis and tenrecs, shrews and hyraxes. Their tiny snouts toughen. Soft hides go real thick as the fur thins, showing off the tough hide, which is pinkish-yellow in hue, gleaming under the sun, and what’s there to eat, there’s nothing to eat, we must find something to eat, and so they dig. A hoof appears.

But the hoof is lousy at digging. It cleaves thrice and voilà! Lose the pollex, enter the claws, each a thick spoon. Enter the ears, long, soft and tubular. Enter the buccal snout, twice as long as a pig’s, half as long as an anteater’s, but it is not an anteater’s; this particular snout holds nine olfactory bulbs, best of anybody out there on the grasslands, stampeding the hot, bitchy savanna—and after another infinity, through the parallel evolution of a far less sturdy mammal, Modern Man, one of whom goes by the name Sir Richard Ostlet (but what are names), and Sir Richard Ostlet assigns to them in 1875 (but what is time) the order Edentata, “without teeth,” before realizing he’s wrong; the creature is, in fact, Tubulidentata. The teeth are there, at the back, by the throat. These dentine tubes, they serve the tongue, which is itself slender, protractile, and covered with a thick, viscous substance to which ants and termites clawed up from the ground will all, from here on out, helplessly adhere—

“Enter Orycteropus into the log,” Ostlet tells his assistant as he examines the claws. “That’s from the Greek. Do you know what it means?”

The young man shakes his head.

“Digging footed,” says Ostlet. “With the ears of a rabbit and snout like a pig. But what to call it?” He begins pacing. “Enter ‘the hare pig.’ The ears and snout tell us they’re guided by hearing and smell—No, wait. Enter ‘the ant bear,’” he says.

But that’s still not right.

He asks one of the African hunters what they call these beasts.

“Aarde vaarke,” the hunter says, and the hunter, black and handsome, does not know that his people adopted the word centuries ago from Dutch colonists as he points: “Earth pig.”

Ostlet nods vigorously. “Enter ‘the aardvark,’” he says, which the young assistant, a student of his in the Department of Naturalism at the University of Edinburgh, obediently enters.

1.

It is August. Congress is in recess. You are not in recess. You are running a reelection campaign for the First Congressional District in Virginia. Your opponent’s name is Nancy Beavers, and you have made up your mind that from here on out there will be no more days off. If you are going to lose your job, it is not going to be to a woman. Not a woman named Nancy. Not a woman named Nancy. Fucking. Beavers.

So you had no intention of taking today off, but today there�

��s a heat wave. Grids are out all over the city. Your grid is one of the ones that are out.

The A/C is not working. The internet is not working. The TV is not working. Nothing is working. You are not working.

You are reposed upon a Victorian sofa the color of canaries that your assistant purchased for you three days ago at a street antique fair for $1900, flipping through the book Images of Greatness: An Intimate Look at the Presidency of Ronald Reagan until you find what you’re looking for: a photograph of the Gipper reclined upon a canary-yellow velvet Victorian sofa.

Important-looking papers cross his chest.

You have looked at this photograph many times—it is the reason why you purchased this sofa, and now that you have it, you are lying on the exact same sofa in the exact same position as Ronald Wilson Reagan.

You turn the page.

There is Dutch, the Gipper, on his ranch, riding a horse chased by piebald foxhounds, the paunch of his stomach outlining a lightweight denim cowboy shirt, and you bought that exact same shirt at the exact same antique fair, and how the flaps of his tan riding pants do crest the tops of his riding boots, you think, and consider sending your assistant to return to the fair to seek out those boots, when the doorbell rings.

Your doorbell is not a buzzer, it’s something more ancient. Like from the Eighties. You wonder who it could be because no one ever comes to your door. Everyone always comes to your office. Then you wonder how the doorbell is working when nothing else is. The doorbell, you realize, is not attached to the grid.

This freaks you out.

It could be Rutledge or Olioke, you think, the two congressmen who stay with you during the week in the extra rooms of your townhouse near the Capitol while Congress is in session, but that’s highly unlikely: Representative William “Billy” Rutledge (D) is back on his farm with his wife and five sons. He left two days ago and won’t be back ’til September. Representative Solomon “Sammy” Olioke (R) is at some cottage with his wife and five daughters. Some crappy cottage by some crappy lake, and Olioke leaves his crap everywhere in your townhouse, he’s crappy at governing, he’s from Rhode Island, he’s been reelected four times, so even though he’s a Republican, you kind of hate Olioke.

The doorbell rings again.

You have no wife, no children. You, like Representative Rutledge, are young, white and handsome, however you are a bachelor. You are fine with this. This was the hallmark of your first campaign (this and abortion). It’s how people know you. But now that you are facing reelection, your aides are not fine with this: your Favorability Rating is currently holding steady at 52%, which, although good, is not as good as it could be, and as of late your aides have been telling you to Find A Wife.

If you Find A Wife, they say, your Favorability Rating will improve, because although you are neck and neck with Nancy Fucking Beavers, a middle-aged woman with an ass like two neighborly cast-iron skillets who wears these unbelievable pantsuits—Nancy Fucking Beavers is not fucking single. She has fucking children. Your platform is Bachelor and her platform is Children, and you are trying to wrap your brain matter around the fact that many people who should constitute your electorate will actually trust Nancy Fucking Beavers more than they trust you simply because she has children, roundly discarding the fact that her only experience in government is losing a local mayoral campaign by a hair, when the doorbell rings a third time.

You go upstairs. You put on your bathrobe.

Your bathrobe is navy blue with red piping and cost $398. It is monogrammed “APW” in Chancery on the breast pocket and is Egyptian cotton from Bill Blass, Ronald Reagan’s favorite designer. There is a picture of Reagan wearing the bathrobe in Images of Greatness, from when he got shot, and you always feel pretty good wearing the bathrobe, which is why, even though it’s so hot out, you put on the bathrobe.

You wear an oxford underneath. Like Reagan. Even after he got shot, he wore an oxford underneath.

You are less of a man than Ronald Reagan, you know this, but no one will ever be able to say about you that your goals were not lofty, you think as you return downstairs and open the door.

1875

Sir Richard Ostlet, a fifty-year-old, richly mustachioed zoological naturalist, is in the Karoo beds of southern Africa, an area that will one day be known as Namibia, searching for strange mammals to bring home to Britain, and these particular mammals, the aardvarks, despite the fact that they have lived for several thousand millennia before Richard Ostlet, to him, fit the bill.

They look like some kind of joke, Ostlet thinks, like some kind of accident, part rabbit, part pig, or even part kangaroo, but in reality, the aardvark is none of these things; nor is it strange to the two African hunters working for Ostlet who kill these beasts regularly, for sport and/or meat, and who are, at this moment, presenting him with three high-quality specimens rooted out from their long, sandy tunnels last night.

Of the three specimens, one immediately stands out to Ostlet. Marvelously humpbacked, profoundly clawed, she is the oldest and therefore largest of the three, and reminds the naturalist of something but he cannot say what. For whatever it is, it’s neither the hypotrichous skin, yellow-pink, nor the four earth-colored limbs—plantigrade at the front, digitigrade at the back—and it’s not the round, wrinkled scalp common to Ungulata and other hooved mammals, nor the ears, folded like silk, nor the stretched piggy snout with its coarse whiskers that cluster the nostrils, bridge the nose and even sprout from the cheeks—it’s something in the eyes, he thinks, which are soft, long-lashed, making her expression flirtatious yet noble, like an intelligent dog, and as the others leave Ostlet to dine in a nearby tent, he continues to stare at the dead aardvark, surprising himself when he sees in the face a kind of melancholy, he hasn’t felt this sad in years, and the burden is so sudden, so heavy, his first instinct is to share it, to split it with someone.

But there is no one there with whom to split it.

For Ostlet cannot say to his assistant “enter the melancholy, like a reckoning” or “enter the malaise, like a frozen groundswell,” and so: a plan is formed. This aardvark is selected. The carcass will be preserved for the boat back to England, and the skin, skeleton, notes and all sketches, will be delivered to Ostlet’s close friend, the taxidermist Mr. Titus Downing of Royal Leamington Spa, the only man in the world, Sir Richard Ostlet believes, who might actually be able to do the aardvark justice.

The aardvark will make it to Leamington Spa.

Ostlet will not.

Late that night, the man, who is newly married to a slim, pretty botanist named Rebecca, and who, mere months ago, signed a lease on a lovely new flat on the lovely Gloucester Walk between Holland and Hyde, two of the loveliest parks in London; the man who participates in all the social “field clubs” such as the Midland Union, the Yorkshire Naturalists Union, the prestigious Cotteswold Club, which serves its members seedcakes and champagne; the man who, up to this moment, has been considered by all he knows to be wholly openhearted, privileged with a preternaturally optimistic disposition, one he has enjoyed since his youth, will find himself awake in the dark tent in Africa, driven out of his dreams.

Richard Ostlet will rise from his cot and root through his small wooden cabinet of gear, which is five rows of cork-lined drawers, each papered and stuffed with the accoutrements général of any naturalist: the chalk tins and marking pins, the white gum erasers, round prickly sponges, lidded glass jars, brown bottles of chloroform, and above all, numerous white lumps of camphor, which are necessary for the preservation of the specimens; and this is an irony Ostlet does not consider as he removes the camphor lumps from their drawers, grabs a bottle of whiskey, and, one by one, ingests them, pill-like, to his death.

* * *

The man at the door is wearing a purple and black FedEx uniform. He is carrying a FedEx clipboard and behind him, a white FedEx truck hums in the heat. It’s FedEx.

“Representative Wilson?” he says.

“Yes,” you say.

“Sign here,” he says.

The man is an average height, a bit on the round side maybe, and sports a long brown beard, these funny-looking thick eyeglasses, and you will swear that these are the only details about him you are able to recall when you are seated in front of a congressional committee for your impeachment hearing—but that has not happened yet. That will not happen for another six weeks. Right now your only concern is the very large cardboard box with your name on it, which is standing, upright, behind the FedEx man. There is no return address.

“What is it,” you say. “Who’s it from.”

The FedEx man does not answer. He checkmarks the clipboard, walks quickly back to the delivery truck and climbs into the driver’s seat. He drives away.

In the playground across the street where local children go to scream, a chubby black boy stands alone, apart from the others. He is not screaming. He is watching you. He wants to see what’s in the box, and you can hardly blame him: the box is, after all, like, really big. It takes up your whole stoop.

You try and lift it. You cannot lift it.

The boy watches as you try and lift it.

How the hell did the FedEx man carry this thing to your stoop by himself, you wonder, and decide that you need to work out more. Stop eating carbs.

Your assistant, Barb Newberg, eats carbs all the time, but she doesn’t like to eat carbs by herself, so she hauls into your office endless plastic bins of Panera. Oily danish and muffins. Barb and her carbs. Like so many middle-aged women you know, Barb Newberg confuses kindness and gluttony, and it’s really time for a new secretary you think as you examine the box, which is certainly big and certainly heavy and all blank but for the taped seams, your name and your address in Foggy Bottom, which is 2486 Asher Place in the fine and fair city of Washington, DC.

You stop for a second and consider: maybe you shouldn’t bring something inside the house without knowing its makeup or origin (the post-9/11 Amerithrax scare when you were an intern has never quite left you), and that is why, standing out here in your bathrobe on the landing of Asher Place Townhouses across the street from the city playground with a chubby black boy staring at you now very intently on one of the hottest days of the year, you leave the box on your stoop, hustle inside to the kitchen and rummage the drawers until you find what you’re looking for: a knife, and it is a small, rust-dotted paring knife belonging to Olioke, which you carry in one hand as you return to the box.