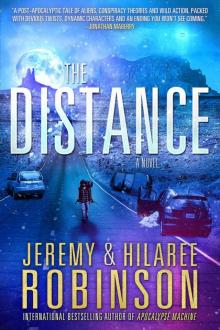

The Distance

Jeremy Robinson

THE DISTANCE

By Jeremy & Hilaree Robinson

Description:

THEIR JOURNEY BEGINS...

The human race has turned to dust. August Morrison faces it after rising from the depths of a dark matter research facility in Arizona. His co-workers. His daughter. All of them: dust. Friends and colleagues around the world don’t answer their phones. The city of Phoenix burns. He is alone. As a world without mankind starts to crumble, August fights not just for survival, but for his very sanity.

On the other side of the country, Poe McDowell watches her parents crumble into dust just moments after being shoved inside a coffin-like device that spares her from the same fate. She emerges to find not just her mother and father, but also her neighbors—her entire town’s human population—reduced to grit. Unlike August, she’s not entirely alone, but the life growing in her belly isn’t much company.

Then, hope. A drunken and desperate August broadcasts over the ham radio network and connects with his fellow survivor, Poe, alone and pregnant in a snow blanketed New Hampshire. Determined to reach her, August sets out on a cross country trek. But the world is not as empty as it seems. Lights in the sky reveal that they are not alone. The human race’s demise was not natural—and the architects are searching for survivors.

...AT THE END.

Jeremy Robinson, whose stories have been compared to Michael Crichton, James Rollins and Stephen King, is the international bestselling master of stories featuring mind-bending imagination, terrifying monsters and high-octane action. With The Distance, he is joined by his wife, Hilaree Robinson, whose passionate writing and characters make this novel a truly unique and exciting experience that will leave readers both enthralled and moved.

THE DISTANCE

Jeremy & Hilaree

Robinson

Table of Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

A NOTE FROM JEREMY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ALSO by JEREMY ROBINSON

For Hil, you’ve taken your first brave step.

Now it’s time to run.

—Jeremy

To Jeremy, my husband of twenty-one adventurous, creative years,

and to my Dad, who when I was seventeen years old said

he wanted the first copy of my first book.

—Hilaree

1

POE

I scream in pain, gripped by his loving-turned-violent hands. He drags me down the stairs, into the basement. My legs bounce over the steps, loose and rubbery, lacking motivation to fight or kick. I’m lost. Confused. She follows us down, her face twisted in an expression I can’t understand beyond a single word: crazy.

They’ve gone mad.

My shin cracks into the corner of the railing’s support post, snapping my mind into crystal clear focus for a moment that drags out, stretched like a rubber band. As I’m forced and shoved downward, time slows enough for me to wonder, how did this happen?

My mind flits back a few hours. I’m sitting on the living room couch, and for some reason, thinking about Todd.

I told him to leave. Actually, that’s not true. I told him to hang himself from a coat rack and die, but the message was essentially the same: go away.

Why? I could give a long list of reasons. The usual trite bullshit that marks the end of every relationship. But the truth is, it’s a long time trait. Probably genetic, skipping a generation, like baldness, but more surly and vocal.

As a short-for-my-age five year old, when adults, bending at the waist, infuriated me with the question of what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said in my tiny squeak, “A hermit on a mountaintop”.

But that never stopped them from trying to pull more words out of me. What I wanted most was the uninterrupted benevolence of solitude. I wanted to draw. I wanted to read. I wanted to observe. I loved the furious insides of my own small head, the container for my big thoughts. Even then, total introversion’s beautiful appeal gripped my imagination, and my self-image materialized as a small, capable pioneer. Alone, on purpose.

I wanted silence. I still do.

And now, wrapped in an ancient, granny-squared afghan in my parents’ living room, feet up on the cracked leather hassock, sketchbook resting beside me, I know why I told the father of my child that he didn’t need to stick around. Because there’s nothing better than autonomy. Because my tiny frame, already showing the no-bigger-than-a-raspberry child, will do just fine on its own.

The crackling woodstove draws me up to a sitting position, heating the living room of the house I grew up in. Fire attracts me. I lift my hands toward the warmth. Dried blue paint clings around my cuticles. Scribbled notes tattoo the back of my left hand. Important things to remember or considerations for in-progress paintings. Call gallery. Emphasize strength—red? Get prenatal vitamins.

I’ll raise that kid myself.

“Woodstoves smell like Frost’s poetry sounds,” my father says, coming in from the barn. The night is black and white behind him, through the open kitchen door; a blizzard swirls through New Hampshire’s forested evening. He stamps his boots against the doorframe, freeing clumps of snow, and hangs his red parka on the hook near the stove.

My mother perches on the edge of a kitchen chair at the table, peeling squash. Quick little movements. Shards of peel fall orange around her feet, somehow missing the table, her mind several steps ahead of her present state. “How’s our little calf?” she asks, not looking back to see if Dad is listening. “Can you get me two more butternuts from the cellar? We’ll have to plant more this year, they grew so well. Maybe more potatoes, too.” She peels, lightning fast. “What did we use for fertilizer this year? Straight manure, right? I was thinking we could try crab meal next year.”

I take the seven steps it requires to reach the kitchen from the couch, and sit across from her at the table, afghan around my shoulders. “Mmm…maybe you could feed the entire town, Mom. That squash smells so weird.” I lean over to sniff it. “Dad didn’t hear you, he’s down cellar already.”

“Poe. You’ve got a little bun in the oven, honey. Everything will smell weird.” She glances over her glasses at me. “And make you want to throw up.”

My father emerges from the cellar and sets the squash down on the table. So he did hear her. Or read her mind, which is more likely. “Make you want to throw up…like being locked in a room, forced to watch reality TV.” He looks off into the middle distance. “No. That doesn’t quite work.”

We stare at each other, thinking. “Like riding a roller coaster,” he says. “In July.” My father and I ponder in images, analyze and articulate with visual illustrations of our thoughts. W

e’re cute together that way, and have formed careers out of our commonality—mine as a painter, his as a poet.

“Riding a roller coaster in July,” I say, “next to a fat guy who smells of cheese dogs, spilled beer and mustard, and whose tight white T-shirt is soaked through with sweat.”

“Perfect!” He ambles off to the living room, all elbows, knees and shoulders, smiling.

My mother, mentally filtering out our visual aid, continues where she left off. “Obviously we’ll need more tomatoes, maybe more cherry. Those sweet ones you like, Poe. Can just pop them in your mouth.” The endless provider of food tips her gray ponytailed head, thinking.

I grab a second peeler from the drawer and start in on squash number two, not because I’m helpful, or hungry, but because I want the smell to go away, and that’s not going to happen until these gourds are stripped naked, diced, boiled, buttered and consumed.

Toward the end of dinner, the inevitable.

“You really should consider just moving back here with us, Poesy,” my father half mumbles, using my lifelong nickname, his mouth full of chicken they raised and butchered themselves. “With the little squirt. It doesn’t matter how old you are. Who cares? The shit’s going to hit the fan before you know it. We’re under constant threat. Humanity is vulnerable, although we think we’re not.” He leans back in his chair, hands behind his head, arms creating huge triangle wings, convinced and casual about it.

Here we go, I think. During my late teenagehood, my parents began dabbling in all things supernatural and weird, whether it was crop circles, ghosts, or time travel. You name it. Aliens were the big topic. UFOs. Abductions. Crazy stuff, like those people on Unsolved Mysteries, but without the far off look in their eyes. That was always the difference. Despite the crazy, my parents always seemed lucid and thoughtful.

I went to college at MassArt in Boston, and was happy to leave them a few hours behind me, up north, getting embroiled in their ‘research.’ It affected their political leanings and their relation-ships with friends. Ten years later, their superstitions and concerns for humanity’s well-being are causing them to seriously consider becoming survivalists. They bought the cow this past year. Of course, when I mention all this to friends, they say I’m lucky to have such sane parents. I can see their point. They’re not angry. They hardly ever fight.

My mother fiddles with her burgundy prayer shawl, one her sister knitted for her, adjusting it over her thin frame. Wisps of gray hair are tucked behind her ears, girlish. She leans forward and extends her hand to me. I let her squeeze my fingers. “How many people have the Hochman’s now? Poe? How many?”

I don’t answer.

Not because I can’t, but because the number numbs me. Over ten thousand cases of the disease worldwide, spread by a virus. Ten thousand, including the dead and dying. Compared to the flu, it still wasn’t the world’s number one killer virus, but it was the most deadly. While the very young and very old are at mortal risk from the flu, Hochman’s kills everyone, even the healthiest of us. Here in New Hampshire, there hasn’t been a single reported case. Yet. Massachusetts is up to thirty, so it probably won’t be long before it crosses the border, a refugee looking for a new home, always looking for a new home. Each host dies within five days. But maybe our smaller and more spread out population will slow it down?

My mother continues, doom and gloom like mist in the air, thick. “You honestly think we’re all going to be just fine?”

I want to get up and leave; I feel irritated, pregnant and tired. I want to go back to my quiet apartment and work on a painting, but one look outside, at the raging blizzard, reminds me why I came here tonight. My crappy apartment building, with its crumbling brick façade and old, drafty horsehair plaster walls insulated by centuries-old layers of wallpaper, will likely lose power. A heatless home in central NH, in February, gets too cold fast. My pipes will probably be frozen when I return.

My parents, of course, have a generator, with enough propane to blow up the state. And there’s always the woodstove. Many chilly childhood nights, before the generator purchase, were spent camping in the living room, woodstove raging, a line of sleeping bags on the braided rug.

“I’m having a baby,” I tell my mother, and stand up, clearing dishes and avoiding the sour subject. My mother understands. Any woman who has carried a baby would. A bleak future cannot be considered lightly, over a meal, while growing a soul that will have to deal with whatever hell awaits. She gives me a nimble pat on the back, freeing me from the conversation, and heads to her chair in the living room. Then she sits down and picks up her knitting, knowing I’ll insist on doing all the dishes.

I watch my mother while rinsing dishes, the fork clanking loudly as I scrape clinging potatoes into the garbage disposal. I can see her from the kitchen sink, her legs folded beneath her on the chair. We sit the same way, our light, muscular frames always bent into pretzels. She’s knitting socks, beautiful already, terra cotta orange yarn, flecks of green, her hands ever busy. She’s tiny and energetic, like me. Our hands constantly create. This is what I’ll look like thirty years from now, my child cleaning the dishes.

“Dad, you write anything new recently?” I run the hot water, filling the deep, white porcelain sink with bubbles. Five years ago, my father was nominated for the Pulitzer in poetry. He lost to a woman from Nigeria.

I shiver a little—it’s cold in the kitchen, despite the crackling woodstove. I roll up my sweater sleeves and sink my arms deep into the water. “You guys should put some plastic up over these windows.”

My father steps up beside me, eying the goodies on the stovetop. “Eh, we’ll see. I’ve got a few pieces in the works. How about you? Is that gallery in Portsmouth showing your new series or some of your older stuff?” He helps himself to another piece of strawberry rhubarb pie, one of two featured pies at dinner. This one he baked himself, the strawberries and rhubarb from their prodigious garden, waiting in the freezer for a year.

The television in the living room comes on, my mother blinking at the bright screen. She’s watching the news. I have to talk over it.

“The exhibit’s next week, actually. My new stuff. You know, the really huge canvases. They want six of them, which is amazing. They’ll take up the whole gallery.”

A weatherman drones on, like we didn’t already know about the snow. Been snowing all day. It’ll continue heavily through the night. Storm of the year. Potential for three feet. I hear the channel change to some sitcom rerun. Seinfeld. An episode where Jerry finds out yet another new woman in his life is minutely flawed and runs the other way. Screw you, Jerry, I think. Who needs you? I don’t even watch your damn show.

My father brings more plates to the sink. Pie crust crumbs cling to his short white beard. “You’re a mess,” I say, and I brush him off, my wet hand dripping water on his blue plaid flannel shirt. The shirt matches his eyes. He taps my nose once with his fingertip, and I turn back to the soapy water. Snow is beginning to stick to the kitchen window above the sink, a ring of white.

He leans against the counter and wipes the old dishes, stacking them dry on the table. “I think those are some of your best. The colors are so vivid. You’re like a young Frida Kahlo. My little Poesy.”

I feel shy. He’s never complimented my painting in that way before. “But without the bushy unibrow.” I hand him a rinsed plate.

He snorts. “Like Kahlo if she…” he starts, when my mother screams from the other room.

“Calvin! It’s happening. I think it’s happening!”

The plate slips from his fingers and drops to the oak floor. It shatters. Shards slide across the kitchen, under the table, under the refrigerator. He ignores them and crunches right over the pieces in his LL Bean moccasins, straight to my mother. She’s standing in front of the television, her knitting needles in one hand, half-finished orange sock in the other.

I follow my father. “Dad, you broke a plate!”

He ignores me and stands there next to my mother, e

yes wide, focused on their television.

I’m annoyed and confused. Waves of pixilation distort Jerry Seinfeld’s face, like he’s melting into squares. The storm. We’ll lose power soon, if the dish on the roof is being affected—an indicator of snow accumulation and windy conditions.

“I can feel it,” my mother says. “Can’t you?”

My father nods, but it’s non-committal.

I want to shake them. What’s the big deal? We’re a bunch of hardy old New Englanders.

“Okay, so…Dad, you want me to help hook up the generator? I’m gonna clean up that plate first, though.” They ignore me. I’m invisible. I’ve seen them like this before, at the height of their UFO ramblings. But it’s been years since they got this bad.

My mother picks up the remote and changes the channel to a live news report. Local, snowy, a woman in full blizzard gear reporting from the seacoast, twenty miles away.

“In addition to severe snow accumulations ranging from thirty to forty inches, the area is experiencing an audible phenomenon that is slowly increasing in volume…” The reporter flicks in and out of pixilation. And then I hear it. At first I think it’s coming from the report, but no. The electricity flickers and a low grinding noise, like tires stuck on ice—a revving engine—tickles my ears. I head back into the kitchen, to the window, and peer out at the darkened driveway.

There’s no one here, no car, no stuck snowplow. The grinding increases in volume, and I open the kitchen door, squinting into the yard. The barn’s outline is visible through the swirling snow. Wind smacks me in the face, the temperature below zero. I stand there, already shivering, trying to figure out where the noise is coming from, when I hear my parents’ urgent whispering from the other room.

I close the door. The grinding noise now fills the house. I crunch back over the broken plate, lights flickering like a horror movie and start to joke, “Guys, remember that creepy film with—”