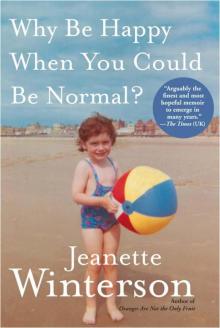

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

Jeanette Winterson

WHY BE HAPPY WHEN YOU

COULD BE NORMAL?

ALSO BY JEANETTE WINTERSON

Fiction

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit

The Passion

Sexing the Cherry

Written on the Body

Art & Lies

Gut Symmetries

The World and Other Places

The Powerbook

Lighthousekeeping

Weight

The Stone Gods

Nonfiction

Art Objects

Comic Book

Boating for Beginners

Children's Books

Tanglewreck

The King of Capri

The Battle of the Sun

The Lion, the Unicorn and Me

Screenplays

Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (BBC TV)

Ingenious (BBC TV)

Jeanette Winterson

Why Be Happy

When You Could

Be Normal?

Grove Press

New York

Copyright © 2011 by Jeanette Winterson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

‘Burnt Norton’ from Four Quartets by T.S. Eliot. Reproduced by kind permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.’The Rowing Endeth’ from The Complete Poems of Anne Sexton by Anne Sexton (Houghton Mifflin, 1981) ©Anne Sexton, reprinted by permission of Sterling Lord Literistic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Jonathan Cape,

The Random House Group, London

Printed in the United States of America

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

ISBN—13: 9780802194756

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

1 2 3 4 5 6 715 14 13 12 11

To my three mothers:

Constance Winterson

Ruth Rendell

Ann S.

With love and thanks to Susie Orbach

Thanks as well to Paul Shearer who traced the family tree.

To Beeban Kidron's helpline! To Vicky Licorish and

the kids: my family. To all my friends who stood by me.

To Caroline Michel — fantastic agent and fabulous friend.

Everyone at Grove for backing this book: Morgan Entrekin,

Elisabeth Schmitz, Deb Seager and Jodie Hockensmith.

And to Heather Schroder at ICM and to AM Homes.

CONTENTS

1The Wrong Crib

2My Advice to Anybody Is: Get Born

3In The Beginning Was The Word

4The Trouble With A Book . . .

5At Home

6Church

7Accrington

8The Apocalypse

9English Literature A—Z

10This Is The Road

11Art and Lies

Intermission

12The Night Sea Voyage

13This Appointment Takes Place In The Past

14Strange Meeting

15The Wound

Coda

1

The Wrong Crib

W

HEN MY MOTHER WAS ANGRY with me, which was often, she said, ‘The Devil led us to the wrong crib.’

The image of Satan taking time off from the Cold War and McCarthyism to visit Manchester in 1960 — purpose of visit: to deceive Mrs Winterson — has a flamboyant theatricality to it. She was a flamboyant depressive; a woman who kept a revolver in the duster drawer, and the bullets in a tin of Pledge. A woman who stayed up all night baking cakes to avoid sleeping in the same bed as my father. A woman with a prolapse, a thyroid condition, an enlarged heart, an ulcerated leg that never healed, and two sets of false teeth —matt for everyday, and a pearlised set for ‘best’.

I do not know why she didn't/couldn't have children. I know that she adopted me because she wanted a friend (she had none), and because I was like a flare sent out into the world — a way of saying that she was here — a kind of X Marks the Spot.

She hated being a nobody, and like all children, adopted or not, I have had to live out some of her unlived life. We do that for our parents — we don't really have any choice.

She was alive when my first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, was published in 1985. It is semi—autobiographical, in that it tells the story of a young girl adopted by Pentecostal parents. The girl is supposed to grow up and be a missionary. Instead she falls in love with a woman. Disaster. The girl leaves home, gets herself to Oxford University, returns home to find her mother has built a broadcast radio and is beaming out the Gospel to the heathen. The mother has a handle — she's called ‘Kindly Light’.

The novel begins: ’Like most people I lived for a long time with my mother and father. My father liked to watch the wrestling, my mother liked to wrestle.‘

For most of my life I've been a bare—knuckle fighter. The one who wins is the one who hits the hardest. I was beaten as a child and I learned early never to cry. If I was locked out overnight I sat on the doorstep till the milkman came, drank both pints, left the empty bottles to enrage my mother, and walked to school.

We always walked. We had no car and no bus money. For me, the average was five miles a day: two miles for the round trip to school; three miles for the round trip to church.

Church was every night except Thursdays.

I wrote about some of these things in Oranges, and when it was published, my mother sent me a furious note in her immaculate copperplate handwriting demanding a phone call.

We hadn't seen each other for several years. I had left Oxford, was scraping together a life, and had written Oranges young — I was twenty—five when it was published.

I went to a phone box — I had no phone. She went to a phone box — she had no phone.

I dialled the Accrington code and number as instructed, and there she was — who needs Skype? I could see her through her voice, her form solidifying in front of me as she talked.

She was a big woman, tallish and weighing around twenty stone. Surgical stockings, fiat sandals, a Crimplene dress and a nylon headscarf. She would have done her face powder (keep yourself nice), but not lipstick (fast and loose).

She filled the phone box. She was out of scale, larger than life. She was like a fairy story where size is approximate and unstable. She loomed up. She expanded. Only later, much later, too late, did I understand how small she was to herself. The baby nobody picked up. The uncarried child still inside her.

But that day she was borne up on the shoulders of her own outrage. She said, ‘It's the first time I've had to order a book in a false name.’

I tried to explain what I had hoped to do. I am an ambitious writer — I don't see the point of being anything; no, not anything at all, if you have no ambition for it. 1985 wasn't the day of the memoir — and in any case, I

wasn't writing one. I was trying to get away from the received idea that women always write about ‘experience’ — the compass of what they know — while men write wide and bold — the big canvas, the experiment with form. Henry James misunderstood Jane Austen's comment that she wrote on small pieces of ivory — i.e. tiny observant minutiae. Much the same was said of Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf. Those things made me angry. In any case, why could there not be experience and experiment? Why could there not be the observed and the imagined? Why should a woman be limited by anything or anybody? Why should a woman not be ambitious for literature? Ambitious for herself?

Mrs Winterson was having none of it. She knew full well that writers were sex—crazed bohemians who broke the rules and didn't go out to work. Books had been forbidden in our house — I'll explain why later — and so for me to have written one, and had it published, and had it win a prize . . . and be standing in a phone box giving her a lecture on literature, a polemic on feminism . . .

The pips — more money in the slot — and I'm thinking, as her voice goes in and out like the sea, ‘Why aren't you proud of me?’

The pips — more money in the slot — and I'm locked out and sitting on the doorstep again. It's really cold and I've got a newspaper under my bum and I'm huddled in my duffel coat.

A woman comes by and I know her. She gives me a bag of chips. She knows what my mother is like.

Inside our house the light is on. Dad's on the night shift, so she can go to bed, but she won't sleep. She'll read the Bible all night, and when Dad comes home, he'll let me in, and he'll say nothing, and she'll say nothing, and we'll act like it's normal to leave your kid outside all night, and normal never to sleep with your husband. And normal to have two sets of false teeth, and a revolver in the duster drawer . . .

We're still on the phone in our phone boxes. She tells me that my success is from the Devil, keeper of the wrong crib. She confronts me with the fact that I have used my own name in the novel — if it is a story, why is the main character called Jeanette?

Why?

I can't remember a time when I wasn't setting my story against hers. It was my survival from the very beginning. Adopted children are self—invented because we have to be; there is an absence, a void, a question mark at the very beginning of our lives. A crucial part of our story is gone, and violently, like a bomb in the womb.

The baby explodes into an unknown world that is only knowable through some kind of a story — of course that is how we all live, it's the narrative of our lives, but adoption drops you into the story after it has started. It's like reading a book with the first few pages missing. It's like arriving after curtain up. The feeling that something is missing never, ever leaves you — and it can't, and it shouldn't, because something is missing.

That isn't of its nature negative. The missing part, the missing past, can be an opening, not a void. It can be an entry as well as an exit. It is the fossil record, the imprint of another life, and although you can never have that life, your fingers trace the space where it might have been, and your fingers learn a kind of Braille.

There are markings here, raised like welts. Read them. Read the hurt. Rewrite them. Rewrite the hurt.

It's why I am a writer — I don't say ‘decided’ to be, or ‘became’. It was not an act of will or even a conscious choice. To avoid the narrow mesh of Mrs Winterson's story I had to be able to tell my own. Part fact part fiction is what life is. And it is always a cover story. I wrote my way out.

She said, ‘But it's not true . . .’

Truth? This was a woman who explained the flash—dash of mice activity in the kitchen as ectoplasm.

There was a terraced house in Accrington, in Lancashire — we called those houses two—up two—down: two rooms downstairs, two rooms upstairs. Three of us lived together in that house for sixteen years. I told my version — faithful and invented, accurate and misremembered, shuffled in time. I told myself as hero like any shipwreck story. It was a shipwreck, and me thrown on the coastline of humankind, and finding it not altogether human, and rarely kind.

And I suppose that the saddest thing for me, thinking about the cover version that is Oranges, is that I wrote a story I could live with. The other one was too painful. I could not survive it.

I am often asked, in a tick—box kind of way, what is ‘true’ and what is not ‘true’ in Oranges. Did I work in a funeral parlour? Did I drive an ice—cream van? Did we have a Gospel Tent? Did Mrs Winterson build her own CB radio? Did she really stun tomcats with a catapult?

I can't answer these questions. I can say that there is a character in Oranges called Testifying Elsie who looks after the little Jeanette and acts as a soft wall against the hurt(ling) force of Mother.

I wrote her in because I couldn't bear to leave her out. I wrote her in because I really wished it had been that way. When you are a solitary child you find an imaginary friend.

There was no Elsie. There was no one like Elsie. Things were much lonelier than that.

I spent most of my school years sitting on the railings outside the school gates in the breaks. I was not a popular or a likeable child; too spiky, too angry, too intense, too odd. The churchgoing didn't encourage school friends, and school situations always pick out the misfit. Embroidering THE SUMMER IS ENDED AND WE ARE NOT YET SAVED on my gym bag made me easy to spot.

But even when I did make friends I made sure it went wrong . . .

If someone liked me, I waited until she was off guard, and then I told her I didn't want to be her friend any more. I watched the confusion and upset. The tears. Then I ran off, triumphantly in control, and very fast the triumph and the control leaked away, and then I cried and cried, because I had put myself on the outside again, on the doorstep again, where I didn't want to be.

Adoption is outside. You act out what it feels like to be the one who doesn't belong. And you act it out by trying to do to others what has been done to you. It is impossible to believe that anyone loves you for yourself.

I never believed that my parents loved me. I tried to love them but it didn't work. It has taken me a long time to learn how to love — both the giving and the receiving. I have written about love obsessively, forensically, and I know/knew it as the highest value. I loved God of course, in the early days, and God loved me. That was something. And I loved animals and nature. And poetry. People were the problem. How do you love another person? How do you trust another person to love you?

I had no idea.

I thought that love was loss.

Why is the measure of love loss?

That was the opening line of a novel of mine — Written on the Body (1992). I was stalking love, trapping love, losing love, longing for love . . .

Truth for anyone is a very complex thing. For a writer, what you leave out says as much as those things you include. What lies beyond the margin of the text? The photographer frames the shot; writers frame their world.

Mrs Winterson objected to what I had put in, but it seemed to me that what I had left out was the story's silent twin. There are so many things that we can't say, because they are too painful. We hope that the things we can say will soothe the rest, or appease it in some way. Stories are compensatory. The world is unfair, unjust, unknowable, out of control.

When we tell a story we exercise control, but in such a way as to leave a gap, an opening. It is a version, but never the final one. And perhaps we hope that the silences will be heard by someone else, and the story can continue, can be retold.

When we write we offer the silence as much as the story. Words are the part of silence that can be spoken.

*

Mrs Winterson would have preferred it if I had been silent.

Do you remember the story of Philomel who is raped and then has her tongue ripped out by the rapist so that she can never tell?

I believe in fiction and the power of stories because that way we speak in tongues. We are not silenced. All of us, when in deep trauma, find we hesitate, we sta

mmer; there are long pauses in our speech. The thing is stuck. We get our language back through the language of others. We can turn to the poem. We can open the book. Somebody has been there for us and deep—dived the words.

I needed words because unhappy families are conspiracies of silence. The one who breaks the silence is never forgiven. He or she has to learn to forgive him or herself.

God is forgiveness — or so that particular story goes, but in our house God was Old Testament and there was no forgiveness without a great deal of sacrifice. Mrs Winterson was unhappy and we had to be unhappy with her. She was waiting for the Apocalypse.

Her favourite song was ‘God Has Blotted Them Out’, which was meant to be about sins, but really was about anyone who had ever annoyed her, which was everyone. She just didn't like anyone and she just didn't like life. Life was a burden to be carried as far as the grave and then dumped. Life was a Vale of Tears. Life was a pre—death experience.

Every day Mrs Winterson prayed,’ Lord, let me die.’ This was hard on me and my dad.

Her own mother had been a genteel woman who had married a seductive thug, given him her money, and watched him womanise it away. For a while, from when I was about three, until I was about five, we had to live with my grandad, so that Mrs Winterson could nurse her mother, who was dying of throat cancer.

Although Mrs W was deeply religious, she believed in spirits, and it made her very angry that Grandad's girlfriend, as well as being an ageing barmaid with dyed blonde hair, was a medium who held seances in our very own front room.

After the seances my mother complained that the house was full of men in uniform from the war. When I went into the kitchen to get at the corned beef sandwiches I was told not to eat until the Dead had gone. This could take several hours, which is hard when you are four.

I took to wandering up and down the street asking for food. Mrs Winterson came after me and that was the first time I heard the dark story of the Devil and the crib . . .