When I Was Mortal

Javier Marías

PRAISE FOR Javier Marías

“Marías is one of the best contemporary writers.”

—J. M. Coetzee

“By far Spain’s best writer today.”

—Roberto Bolaño

“One of the writers who should get the Nobel Prize is Javier Marías.”

—Orhan Pamuk

“Stylish, cerebral.… Marías is a startling talent.… His prose is ambitious, ironic, philosophical and ultimately compassionate.”

—The New York Times

“It is a rare gift, to be offered a writer who lives in our own time but speaks with the intensity of the past, who comes with the extra richness lent by a foreign history and nonetheless knows our own culture inside out. Yet, strangely, Javier Marías—who is famous in Spain and garlanded with prizes from the rest of Europe—remains almost unknown in America. What are we waiting for?”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Javier Marías is one of the greatest living authors. I cannot think of one single contemporary writer that reaches his level of quality. If I had to name one, it would be García Márquez.”

—Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Das Literarische Quartett

“Javier Marías is such an elegant, witty and persuasive writer that it is tempting simply to quote him at length.”

—The Scotsman

“A supreme stylist.”

—The Times (London)

“Marías uses language like an anatomist uses the scalpel to cut away the layers of the flesh in order to lay bare the innermost secrets of that strangest of species, the human being.”

—W. G. Sebald

“His prose possesses an exquisite, almost uncanny observation, re-creating moments and moods in hypnotic depth.”

—The Telegraph (London)

“Javier Marías is a novelist with style.… His readers enter, through him, a strikingly and disturbingly foreign world.”

—Margaret Drabble

“Marías writes the kind of old-fashioned speculative prose we associate with Proust and Henry James.… But he also deals in violence, historical and personal, and in the movie titles, politicians, and brand names and underwear we connect with quite a different kind of writer.”

—London Review of Books

Javier Marías

WHEN I WAS MORTAL

Javier Marías was born in Madrid in 1951. He has published thirteen novels, two collections of short stories, and several volumes of essays. His work has been translated into forty-two languages, in fifty-two countries, and won a dazzling array of international literary awards, including the prestigious Dublin IMPAC award for A Heart So White. He is also a highly practiced translator into Spanish of English authors, including Joseph Conrad, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Thomas Browne, and Laurence Sterne. He has held academic posts in Spain, the United States, and in Britain, as Lecturer in Spanish Literature at Oxford University.

ALSO BY JAVIER MARÍAS

(in order of US publication)

All Souls

Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me

A Heart So White

Dark Back of Time

The Man of Feeling

Your Face Tomorrow 1: Fever and Spear

Written Lives

Voyage Along the Horizon

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream

Your Face Tomorrow 3: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell

Bad Nature, or with Elvis in Mexico

While the Women Are Sleeping

A VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, APRIL 2013

Translation copyright © 1999 by Margaret Jull Costa

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Spain as Cuando fui mortal by Editorial Alfaguara, Madrid, in 1996. Copyright © 1996 by Javier Marías. This translation originally published in slightly different form in Great Britain by The Harvill Press, London, in 1999.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95109-0

www.vintagebooks.com

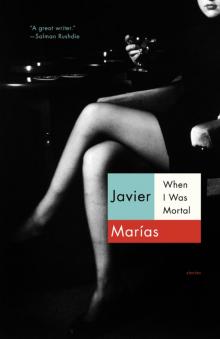

Cover design by Katya Mezhibovskaya

Cover photograph © Nancy Honey / Milenium Images, UK

v3.1

The translator would like to thank Javier Marías, Annella McDermott, and Ben Sherriff for all their help and advice.

M.J.C.

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

The Night Doctor

The Italian Legacy

The Honeymoon

Broken Binoculars

Unfinished Figures

Flesh Sunday

When I Was Mortal

Everything Bad Comes Back

Fewer Scruples

Blood on a Spear

In Uncertain Time

No More Love

PREFACE

Of the twelve stories that make up this volume, I think eleven were commissioned. That means that I did not have absolute freedom when writing those eleven, especially as regards length. Three pages here, ten pages there, forty or so there, the requests are very varied and one tries to fulfil these requirements as best one can. I know that in two of the stories, I found the limitations constraining, which is why they appear here in expanded form, with the space and rhythm which – once begun – they should have had. As for the rest, including those that fulfilled some other external requirement, I don’t think that the commission compromised them in any way, at least not after a time and now that I’ve grown accustomed to them as they are. You can write an article or a story on commission (though not, in my case, a whole book); sometimes even the subject matter may be given and I see nothing wrong in that as long you manage to make the final product yours and you enjoy writing it. Indeed, I can only write something if I’m enjoying myself and I can only enjoy myself if I find the project interesting. It goes without saying that none of these stories would have been written if I had felt no interest in them. It is perhaps worth reminding those sentimental purists who believe that, in order to sit down in front of the typewriter, you have to experience grandiose feelings such as a creative “need” or “impulse”, which are always “spontaneous” or terribly intense, that the majority of the sublime works of art produced over the centuries – especially in painting and music – were the result of commissions or of even more prosaic or servile stimuli.

In the circumstances, however, it may not be out of place to detail briefly how and when these stories were published for the first time and to comment on some of the impositions that soon became absorbed into them and are as much part of the story as any other chosen element. They are arranged in strict chronological order of publication, which does not always coincide with the order in which they were written.

“The Night Doctor” appeared in the magazine Ronda Iberia (Madrid, June 1991).

“The Italian Legacy” was published in the literary supplement of the newspaper El Sol (Madrid, 6 September, 1991).

“The Honeymoon” appeared in the magazine Balcón (special Frankfurt edition, Madrid, October 1991). This story shares the central plot and several paragraphs with a few pages from my novel Corazón tan blanco, 1992 (English transl

ation: A Heart So White, Harvill, 1995). The scene in question continues in the novel, whereas here it breaks off, allowing a different resolution, which is what makes of the text a story. It’s a demonstration of how the same pages may not necessarily be the same pages, as Borges showed, better than anyone, in his story: “Pierre Menard, autor de El Quijote” (“Pierre Menard, author of Don Quixote”).

“Broken Binoculars” was published in the ephemeral magazine La Capital (Madrid, July 1992) with the worst printer’s error ever perpetrated on one of my texts: they failed to print the first page of my typescript, so that the story was published incomplete and starting abruptly in media res. Despite that, it seemed to survive the mutilation. I was asked to write a story with a Madrid setting, although, to be honest, I don’t really know what that means.

“Unfinished Figures” appeared in El País Semanal (Madrid and Barcelona, 9 August, 1992). On this occasion, the commission was positively sadistic. In a very short space I had to include five elements, which were, if I remember rightly: the sea, a storm, an animal … I’ve forgotten the other two, proof that they are now completely absorbed into the story.

“Flesh Sunday” appeared in El Correo Español-El Pueblo Vasco and in Diario Vasco (Bilbao and San Sebastián, 30 August, 1992). In this very short story, the one requirement was, I believe, that it should have a summer setting.

“When I Was Mortal” was published in El País Semanal (Madrid and Barcelona, 8 August, 1993).

“Everything Bad Comes back” formed part of the book Cuentos europeos (Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 1994; published in English as The Alphabet Garden: European Short Stories, ed. Pete Ayrton, Serpent’s Tail, 1994). It’s probably the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written, as will become clear if you read my article “La muerte de Aliocha Coll” included in Pasiones pasadas (Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 1991).

“Fewer Scruples” appeared in the free publication La condición humana (FNAC, Madrid, 1994). This is one of the two stories I have expanded for this edition, by about fifteen per cent.

“Blood on a spear” was published in instalments by El País (27, 28, 29, 30 and 31 August and 1 September 1995). The requirement for this story was that it had to belong more or less to the genre of crime novel or thriller. This is the other story I have since expanded, by about ten per cent.

“In Uncertain Time” was included in the book Cuentos de fútbol, ed. Jorge Valdano (Alfaguara, Madrid, 1995). Obviously, the requirement here was that the story should be about football.

Lastly, “No More Love” is published here for the first time, although the story it tells was contained – in compressed form – in an article, “Fantasmas leídos”, in my collection Literatura y fantasma (Ediciones Siruela, Madrid, 1993). There the story was attributed to a non-existent “Lord Rymer” (in fact, the name of a secondary character in my novel Todas las almas [Editorial Anagrama Barcelona, 1989; English translation: All Souls, Harvill, 1992], the hard-drinking warden of an Oxford college), supposedly an expert and an investigator of real ghosts, if that is not a contradiction in terms. I didn’t like the idea that this short story should remain buried alone in the middle of an article and in almost embryonic form, which is why I have expanded it into this new story. It contains conscious, deliberate and acknowledged echoes of a film and of another story: The Ghost and Mrs Muir by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, about which I wrote an article in my book Vida del fantasma (El País-Aguilar, Madrid, 1995) and “Polly Morgan” by Alfred Edgar Coppard which I included in my anthology Cuentos únicos (Ediciones Siruela, 1989). It’s all perfectly above board, and there’s no question of trying to deceive anyone, which is why the main character of the story is called quite plainly “Molly Morgan Muir”.

These twelve stories were written later than those published in my other volume of short stories, Mientras ellas duermen (Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 1990). There are still a few scattered elsewhere, written very freely or without any commission: it seems advisable to me, however, that they should either remain in obscurity or else scattered.

November 1995

THE NIGHT DOCTOR

For LB, in the present,

And DC, in the past

NOW THAT I know my friend Claudia is a widow – following her husband’s death from natural causes – I keep remembering one particular night in Paris six months ago: I had left at the end of a supper party for seven in order to accompany one of the guests home – she had no car, but lived close by, fifteen minutes there and fifteen minutes back. She had struck me as a somewhat impetuous, rather nice young woman, an Italian friend of my hostess Claudia, who is also Italian, and in whose Paris flat I was staying for a few days, as I had on other occasions. It was the last night of my trip. The young woman, whose name I cannot now remember, had been invited for my benefit, as well as to add a little variety to the supper table or, rather, so that the two languages being spoken were more evenly spread.

During the walk, I had to continue muddling through in my fractured Italian, as I had during half the supper. During the other half, I had muddled through in my even more fractured French, and to tell the truth I was fed up with being unable to express myself correctly to anyone. I felt like compensating for this lack, but there would, I thought, be no chance to do so that night, for by the time I got back to the flat, my friend Claudia, who spoke fairly convincing Spanish, would already have gone to bed with her ageing giant of a husband, and there would be no opportunity until the following morning to exchange a few well-chosen and clearly enunciated words. I felt the stirring of verbal impulses, but I had to repress them. I switched off during the walk: I allowed my Italian friend’s Italian friend to express herself correctly in her own language, and I, against my will and my desire, merely nodded occasionally and said from time to time: “Certo, certo,” without actually listening to what she said, weary as I was with the wine and worn out by my linguistic efforts. As we walked along, our breath visible in the air, I noticed only that she was talking about our mutual friend, which was, after all, quite normal, since, apart from the supper party for seven that we had just left, we had nothing much else in common. Or so I thought. “Ma certo,” I kept saying pointlessly, while she, who must have realized I wasn’t listening, continued talking as if to herself or perhaps out of mere politeness. Until suddenly, still talking about Claudia, I heard a sentence which I understood perfectly as a sentence, but not its meaning, because I had understood it unwittingly and completely out of context. “Claudia sarà ancora con il dottore,” was what I thought her friend said. I didn’t take much notice, because we were nearly at her door, and I was anxious to speak my own language again or at least to be alone so that I could think in it.

There was someone waiting in the doorway, and she added: “Ah no, ecco il dottore,” or something of the sort. It seems the doctor had come to see her husband, who had been too ill to accompany her to the supper party. The doctor was a man of my age, almost young, and he turned out to be Spanish. That may have been why we were introduced, albeit briefly (they spoke to each other in French, my compatriot in his unmistakably Spanish accent), and although I would have happily stayed there for a while chatting to him in order to satisfy my longing for some correct verification, my friend’s friend did not invite me in, but instead bade me a hasty goodbye, giving me to understand or saying that Dr Noguera had been there for some minutes waiting for her. My compatriot the doctor was carrying a black case, like the ones doctors used to have, and he had an old-fashioned face, like someone out of the 1930s: a good-looking man, but gaunt and pale, with the fair, slicked-back hair of a fighter pilot. It occurred to me that there must have been many like him in Paris after the Spanish Civil War, exiled Republican doctors.

When I got back to the apartment, I was surprised to see the light still on in the studio, for I had to pass by the door on my way to the guest room. I peered in, assuming that it had been left on by mistake, and was ready to turn it off, when I saw my friend was still up, curled in an armch

air, in her nightdress and dressing gown. I had never seen her in her nightdress and dressing gown before, despite, over the years, having stayed at her various apartments each time I went to Paris for a few days: both garments were salmon pink, and very expensive. Although the giant husband she had been married to for six years was very rich, he was also very mean, for reasons of character, nationality or age – a relatively advanced age in comparison with Claudia – and my friend had often complained that he only ever allowed her to buy things to further embellish their large, comfortable apartment, which was, according to her, the only visible manifestation of his wealth. Otherwise, they lived more modestly than they needed to, that is, below their means.

I had had barely anything to do with him, apart from the odd supper party like the one that night, which are perfect opportunities for not talking to or getting to know anyone that you don’t already know. The husband, who answered to the strange and ambiguous name of Hélie (which sounded rather feminine to my ears), I saw as an appendage, the kind of bearable appendage that many still attractive, single or divorced women have a tendency to graft onto themselves when they touch forty or forty-five: a responsible man, usually a good deal older, with whom they share no interests in common and with whom they never laugh, but who is, nevertheless, useful to them in their maintaining a busy social life and organizing suppers for seven as on that particular night. What struck one about Hélie was his size: he was nearly six foot five and fat, especially round the chest, a kind of Cyclopean spinning top poised on two legs so skinny that they looked like one; whenever I passed him in the corridor, he would always sway about and hold out his hands to the walls so as to have something to lean on should he slip; at suppers, of course, he sat at one end of the table because, otherwise, the side on which he was installed would have been filled to capacity by his enormous bulk and would have looked unbalanced, with him sitting alone opposite four guests all crammed together. He spoke only French and, according to Claudia, was a leading light in his field – the law. After six years of marriage, it wasn’t so much that my friend seemed disillusioned, for she had never shown much enthusiasm anyway, but she seemed incapable of disguising, even in the presence of strangers, the irritation we always feel towards those who are superfluous to us.