The Thurber Carnival

James Thurber

James Thurber

THE THURBER CARNIVAL

Contents

Foreword

Preface: My Fifty Years with James Thurber

1

The Thurber Merry-Go-Round

The Lady on 142

The Catbird Seat

Memoirs of a Drudge

The Cane in the Corridor

The Secret Life of James Thurber

Recollections of the Gas Buggy

2

From My World and Welcome to it:

What Do You Mean It Was Brillig?

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

Here Lies Miss Groby

The Man Who Hated Moonbaum

The Macbeth Murder Mystery

A Ride with Olympy

3

From Let Your Mind Alone:

Destructive Forces in Life

Sex Ex Machina

The Breaking Up of the Winships

The Admiral on the Wheel

A Couple of Hamburgers

Bateman Comes Home

Doc Marlowe

The Wood Duck

4

From The Middle-Aged Man on the Flying Trapeze:

The Departure of Emma Inch

There’s an Owl in My Room

The Topaz Cufflinks Mystery

Snapshot of a Dog

Something to Say

The Kerb in the Sky

The Black Magic of Barney Haller

If Grant had been Drinking at Appomattox

The Remarkable Case of Mr Bruhl

The Luck of Jad Peters

The Greatest Man in the World

The Evening’s at Seven

One is a Wanderer

5

My Life and Hard Times:

Preface to a Life

The Night the Bed Fell

The Car We Had To Push

The Day The Dam Broke

The Night The Ghost Got In

More Alarms at Night

A Sequence of Servants

The Dog That Bit People

University Days

Draft Board Nights

A Note at the End

6

From Fables for Our Time and Illustrated Poems:

The Birds and the Foxes

The Little Girl and the Wolf

The Scotty Who Knew Too Much

The Very Proper Gander

The Bear Who Let It Alone

The Shrike and the Chipmunks

The Seal Who Became Famous

The Crow and the Oriole

The Moth and the Star

The Glass in the Field

The Rabbits Who Caused All The Trouble

The Owl Who Was God

The Unicorn in the Garden

Excelsior

Oh When I Was …

Barbara Frietchie

The Sands O’ Dee

Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight

7

From The Owl in the Attic:

The Pet Department

8

From The Seal in the Bedroom:

‘With You I Have Known Peace, Lida, and Now You Say You’re Going Crazy’

‘Are You the Young Man That Bit My Daughter?’

‘Here’s a Study for You, Doctor – He Faints’

‘Mamma Always Gets Sore and Spoils the Game for Everybody’

‘For the Last Time – You and Your Horsie Get Away from Me and Stay Away!’

‘Well, What’s Come Over You Suddenly?’

‘Have You People Got Any ·38 Cartridges?’

‘The Father Belonged to Some People Who Were Driving Through in a Packard’

‘Stop Me!’

‘I Don’t Know. George Got It Somewhere’

‘All Right, Have It Your Way – You Heard a Seal Bark’

The Bloodhound and the Bug

9

From Men, Women and Dogs:

‘This Is Not the Real Me You’re Seeing, Mrs Clisbie’

‘What’s Come Over You Since Friday, Miss Schemke?’

‘Hello, Darling – Woolgathering?’

‘It’s a Naïve Domestic Burgundy Without Any Breeding, But I Think You’ll Be Amused by Its Presumption’

‘Oh, Doctor Conroy – Look!’

‘I’d Feel a Great Deal Easier If Her Husband Hadn’t Gone to Bed’

‘Touché!’

‘And This Is Tom Weatherby, an Old Beau of Your Mother’s. He Never Got to First Base’

‘Perhaps This Will Refresh Your Memory’

‘… And Keep Me a Normal, Healthy Girl’

‘It’s Parkins, Sir; We’re ’Aving a Bit of a Time Below Stairs’

‘Darling, I Seem to Have This Rabbit’

‘That’s My First Wife Up There, and This Is the Present Mrs Harris’

‘You’re Not My Patient, You’re My Meat, Mrs Quist’

‘She Has the True Emily Dickinson Spirit Except That She Gets Fed Up Occasionally’

‘I Said the Hounds of Spring Are on Winter’s Traces – But Let It Pass, Let It Pass!’

‘For Heaven’s Sake, Why Don’t You Go Outdoors and Trace Something!’

‘I Don’t Want Him to Be Comfortable If He’s Going to Look Too Funny’

‘Yoo-hoo, It’s Me and the Ape Man’

‘Look Out! Here They Come Again!’

‘You Wait Here and I’ll Bring the Etchings Down’

‘Well, Who Made the Magic Go Out of Our Marriage – You or Me?’

House and Woman

‘Well, If I Called the Wrong Number, Why Did You Answer the Phone?’

‘This Gentleman Was Kind Enough to See Me Home, Darling’

‘I Come From Haunts of Coot and Hern!’

‘Well, I’m Disenchanted, Too. We’re All Disenchanted’

‘What Do You Want to Be Inscrutable for, Marcia?’

‘You Said a Moment Ago That Everybody You Look at Seems to Be a Rabbit. Now Just What Do You Mean by That, Mrs Sprague?’

‘Why, I Never Dreamed Your Union Had Been Blessed With Issue!’

‘Have You Seen My Pistol, Honey-bun?’

‘It’s Our Own Story Exactly! He Bold as a Hawk, She Soft as the Dawn’

‘You and Your Premonitions!’

‘All Right, All Right, Try It That Way! Go Ahead and Try It That Way!’

‘Well, It Makes a Difference to Me!’

‘There’s No Use You Trying to Save Me, My Good Man’

Man in Tree

‘What Have You Done With Dr Millmoss?’

The War Between Men and Women

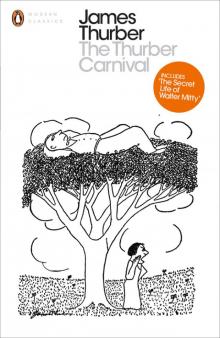

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

THE THURBER CARNIVAL

James Thurber was born in 1894 at Columbus, Ohio, where, as he once said, so many awful things happened to him. After university (Ohio State) he worked at the American Embassy in Paris from 1918 to 1920, and then turned to journalism. From 1927 onwards he was on the staff of the New Yorker, and first published much of his work in it.

Thurber’s art was easy to recognize but hard to define. He created a world in which mournfully sagacious hounds loom over frightened little men who are trying desperately to master life’s problems. His drawings and prose alike were marked by economy, wry humour, and an inimitable blend of precision and fantasy. Perhaps his most justly famous character was Walter Mitty, whose Secret Life gloriously makes up for the shy young man’s failures in competitive real life.

In later life James Thurber became increasingly blind. He died in New York in 1961. In an Observer appreciation, Paul Jennings wrote that ‘he somehow gave us a sense of revelation … He created a genre and was a giant in it.’

For

HAROLD ROSS

with increasing admiration,

won

der, and affection

Foreword

FOR their helpful advice and criticism I want to thank Helen Thurber, Gus Lobrano, Kenneth MacLean, and John McGiffert. I am indebted to The New Yorker for permission to include many of the pieces and drawings which originally appeared in that magazine.

Most of the books represented here were published in America under the supervision of the late Gene Saxton, and this anthology was his idea. I salute the memory of a good friend and a wise and kindly counsellor.

Preface

My Fifty Years with James Thurber

I have not actually known Thurber for fifty years, since he was only forty-eight on his last birthday, but the publishers of this volume felt that ‘fifty’ would sound more effective than ‘forty-eight’ in the title of an introduction to so large a book, a point which I was too tired to argue about.

James Thurber was born on a night of wild portent and high wind in the year 1894, at 147 Parsons Avenue, Columbus, Ohio. The house, which is still standing, bears no tablet or plaque of any description, and is never pointed out to visitors. Once Thurber’s mother, walking past the place with an old lady from Fostoria, Ohio, said to her, ‘My son James was born in that house’, to which the old lady, who was extremely deaf, replied, ‘Why, on the Tuesday morning train, unless my sister is worse.’ Mrs Thurber let it go at that.

The infant Thurber was brought into the world by an old practical nurse named Margery Albright, who had delivered the babies of neighbour women before the Civil War. He was, of course, much too young at the time to have been affected by the quaint and homely circumstances of his birth, to which he once alluded, a little awkwardly, I think, as ‘the Currier and Ives, or old steel engraving, touch, attendant upon my entry into this vale of tears’. Not a great deal is known about his earliest years, beyond the fact that he could walk when he was only two years old, and was able to speak whole sentences by the time he was four.

Thurber’s boyhood (1900–13) was pretty well devoid of significance. I see no reason why it should take up much of our time. There is no clearly traceable figure or pattern in this phase of his life. If he knew where he was going, it is not apparent from this distance. He fell down a great deal during this period, because of a trick he had of walking into himself. His gold-rimmed glasses forever needed straightening, which gave him the appearance of a person who hears somebody calling but can’t make out where the sound is coming from. Because of his badly focused lenses, he saw, not two of everything, but one and a half. Thus, a four-wheeled wagon would not have eight wheels for him, but six. How he succeeded in preventing these two extra wheels from getting into his work, I have no way of knowing.

Thurber’s life baffles and irritates the biographer because of its lack of design. One has the disturbing feeling that the man contrived to be some place without actually having gone there. His drawings, for example, sometimes seem to have reached completion by some other route than the common one of intent.

The writing, is, I think, different. In his prose pieces he appears always to have started from the beginning and to have reached the end by way of the middle. It is impossible to read any of the stories from the last line to the first without experiencing a definite sensation of going backward. This seems to me to prove that the stories were written and did not, like the drawings, just suddenly materialize.

Thurber’s very first bit of writing was a so-called poem entitled ‘My Aunt Mrs John T. Savage’s Garden at 185 South Fifth Street, Columbus, Ohio’. It is of no value or importance except insofar as it demonstrates the man’s appalling memory for names and numbers. He can tell you to this day the names of all the children who were in the fourth grade when he was. He remembers the phone numbers of several of his high-school chums. He knows the birthdays of all his friends and can tell you the date on which any child of theirs was christened. He can rattle off the names of all the persons who attended the lawn fête of the First M.E. Church in Columbus in 1907. This ragbag of precise but worthless information may have helped him in his work, but I don’t see how.

I find, a bit to my surprise, that there is not much else to say. Thurber goes on as he always has, walking now a little more slowly, answering fewer letters, jumping at slighter sounds. In the past ten years he has moved restlessly from one Connecticut town to another, hunting for the Great Good Place, which he conceives to be an old Colonial house, surrounded by elms and maples, equipped with all modern conveniences, and overlooking a valley. There he plans to spend his days reading Huckleberry Finn, raising poodles, laying down a wine cellar, playing boules, and talking to the little group of friends which he has managed somehow to take with him into his crotchety middle age.

This book contains a selection of the stories and drawings the old boy did in his prime, a period which extended roughly from the year Lindbergh flew the Atlantic to the day coffee was rationed. He presents this to his readers with his sincere best wishes for a happy new world.

JAMES THURBER

1

THE THURBER MERRY-GO-ROUND

The Lady on 142

The train was twenty minutes late, we found out when we bought our tickets, so we sat down on a bench in the little waiting room of the Cornwall Bridge station. It was too hot outside in the sun. This midsummer Saturday had got off to a sulky start, and now, at three in the afternoon, it sat, sticky and restive, in our laps.

There were several others besides Sylvia and myself waiting for the train to get in from Pittsfield: a coloured woman who fanned herself with a Daily News, a young lady in her twenties reading a book, a slender, tanned man sucking dreamily on the stem of an unlighted pipe. In the centre of the room, leaning against a high iron radiator, a small girl stared at each of us in turn, her mouth open, as if she had never seen people before. The place had the familiar, pleasant smell of railroad stations in the country, of something compounded of wood and leather and smoke. In the cramped space behind the ticket window, a telegraph instrument clicked intermittently, and once or twice a phone rang and the stationmaster answered it briefly. I couldn’t hear what he said.

I was glad, on such a day, that we were going only as far as Gaylordsville, the third stop down the line, twenty-two minutes away. The stationmaster had told us that our tickets were the first tickets to Gaylordsville he had ever sold. I was idly pondering this small distinction when a train whistle blew in the distance. We all got to our feet, but the stationmaster came out of his cubby-hole and told us it was not our train but the 12.45 from New York, northbound. Presently the train thundered in like a hurricane and sighed ponderously to a stop. The stationmaster went out on to the platform and came back after a minute or two. The train got heavily under way again, for Canaan.

I was opening a pack of cigarettes when I heard the stationmaster talking on the phone again. This time his words came out clearly. He kept repeating one sentence. He was saying, ‘Conductor Reagan on 142 has the lady the office was asking about.’ The person on the other end of the line did not appear to get the meaning of the sentence. The stationmaster repeated it and hung up. For some reason, I figured that he did not understand it either.

Sylvia’s eyes had the lost, reflective look they wear when she is trying to remember in what box she packed the Christmas-tree ornaments. The expressions on the faces of the coloured woman, the young lady, and the man with the pipe had not changed. The little staring girl had gone away.

Our train was not due for another five minutes, and I sat back and began trying to reconstruct the lady on 142, the lady Conductor Reagan had, the lady the office was asking about. I moved nearer to Sylvia and whispered, ‘See if the trains are numbered in your timetable.’ She got the timetable out of her handbag and looked at it. ‘One forty-two,’ she said, ‘is the 12.45 from New York.’ This was the train that had gone by a few minutes before. ‘The woman was taken sick,’ said Sylvia. ‘They are probably arranging to have a doctor or her family meet her.’

The coloured woman looked around at her briefly. The youn

g woman, who had been chewing gum, stopped chewing. The man with the pipe seemed oblivious. I lighted a cigarette and sat thinking. ‘The woman on 142,’ I said to Sylvia, finally, ‘might be almost anything, but she definitely is not sick.’ The only person who did not stare at me was the man with the pipe. Sylvia gave me her temperature-taking look, a cross between anxiety and vexation. Just then our train whistled and we all stood up. I picked up our two bags and Sylvia took the sack of string beans we had picked for the Connells.

When the train came clanking in, I said in Sylvia’s ear, ‘He’ll sit near us. You watch.’ ‘Who? Who will?’ she said. ‘The stranger,’ I told her, ‘the man with the pipe.’

Sylvia laughed. ‘He’s not a stranger,’ she said. ‘He works for the Breeds.’ I was certain that he didn’t. Women like to place people; every stranger reminds them of somebody.

The man with the pipe was sitting three seats in front of us, across the aisle, when we got settled. I indicated him with a nod of my head. Sylvia took a book out of the top of her overnight bag and opened it. ‘What’s the matter with you?’ she demanded. I looked around before replying. A sleepy man and woman sat across from us. Two middle-aged women in the seat in front of us were discussing the severe griping pain one of them had experienced as the result of an inflamed diverticulum. A slim, dark-eyed young woman sat in the seat behind us. She was alone.

‘The trouble with women,’ I began, ‘is that they explain everything by illness. I have a theory that we would be celebrating the twelfth of May or even the sixteenth of April as Independence Day if Mrs Jefferson hadn’t got the idea her husband had a fever and put him to bed.’

Sylvia found her place in the book. ‘We’ve been all through that before,’ she said. ‘Why couldn’t the woman on 142 be sick?’

That was easy. I told her. ‘Conductor Reagan,’ I said, ‘got off the train at Cornwall Bridge and spoke to the stationmaster. “I’ve got the woman the office was asking about,” he said.’

Sylvia cut in. ‘He said “lady”.’