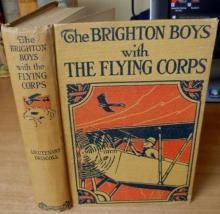

Brighton Boys with the Flying Corps

James R. Driscoll

Produced by Jim Ludwig

THE BRIGHTON BOYS WITH THE FLYING CORPS

by Lieutenant James R. Driscoll

CONTENTS

CHAPTERS I. The Brighton Flying Squadron II. First Steps III. In the Air IV. Off for the Front V. Jimmy Hill Startles the Veterans VI. The Fight in the Air VII. Parker's Story VIII. Thrills of the Upper Reaches IX. In the Enemy's Country X. Planning the Escape XI. Through the Lines XII. Pluck and Luck XIII. The Raid on Essen XIV. A Furious Battle

CHAPTER I

THE BRIGHTON FLYING SQUADRON

"The war will be won in the air."

The headlines in big black type stared at Jimmy Hill as he stood besidethe breakfast table and looked down at the morning paper, which layawaiting his father's coming.

The boys of the Brighton Academy, among whom Jimmy was an acknowledgedleader, had been keenly interested in the war long before the UnitedStates joined hands with the Allies in the struggle to save smallnations from powerful large ones---the fight to ensure freedom andliberty for all the people of the earth.

A dark, lithe, serious young French lad, Louis Deschamps, whose motherhad brought him from France to America in 1914, and whose father wasa colonel of French Zouaves in the fighting line on the Western Front,was a student at the Academy. Interest in him ran high and with itran as deep an interest in the ebbing and flowing fortunes of France.The few letters Mrs. Deschamps received from Louis' soldier fatherhad been retailed by the proud boy to his fellows in the school untilthey knew them by heart.

Bob Haines' father, too, had helped fan the war-fire in the hearts ofthe boys. Bob was a real favorite with every one. He captained thebaseball team, and could pitch an incurve and a swift drop ball thatmade him a demi-god to those who had vainly tried to hit his twisters.Bob's father was a United States Senator, who, after the sinking ofthe _Liusitania_, was all for war with Germany. America, in his eyes,was mad to let time run on until she should be dragged into theworld-conflict without spending every effort in a nationalgetting-ready for the inevitable day. Senator Haines' speeches werematter-of-fact----just plain hammering of plain truths in plainEnglish. Many of his utterances in the Senate were quoted in thelocal papers, and Bob's schoolmates read them with enthusiasm whenthey were not too long.

Then, too, a number of the Brighton boys had already entered theservice of Uncle Sam. Several were already at the front and hadwritten thrilling letters of their experiences in the trenches, atclose grip with the Boches. Still more thrilling accounts had comefrom some of their former classmates who were in the Americansubmarine service. Other Brighton boys who had gone out from theiralma mater to fight the good fight for democracy had helped to fanthe flame of patriotism.

So the school gradually became filled with thoughts of war, and almostevery boy from fourteen years of age upward planned in his heart ofhearts to one day get into the fray in some manner if some longed-foropportunity ever presented itself.

Jimmy Hill---who was fortunate in that his home was within walkingdistance of the Academy---commenced his breakfast in silence. Mr.Hill read his paper and Mrs. Hill read her letters as they proceededleisurely with the morning meal. The porridge and cream and then twoeggs and a good-sized piece of ham disappeared before Jimmy's appetitewas appeased, for he was a growing boy, who played hard when he wasnot hard at some task. Jimmy was not large for his age, and hisrather slight figure disguised a wiriness that an antagonist of hissize would have found extraordinary. His hair was red and his faceshowed a mass of freckles winter and summer. Jimmy was a bright,quick boy, always well up in his studies and popular with his teachers.At home Jimmy's parents thought him quite a normal boy, with anunusually large fund of questions ever at the back of his nimbletongue.

Breakfast went slowly for Jimmy that morning when once he had finishedand sat waiting for his parents. Mr. Hill was scanning the back pageof the paper in deep concentration. Again the big black letters staredout at Jimmy. "The war will be won in the air." Jimmy knew wellenough what that meant, or at least he had a very fair idea of itsmeaning. But he had sat still and quiet for a long time, it seemed tohim. Finally his patience snapped.

"Father," he queried, "how will the war be won in the air?"

"It won't," was his father's abrupt reply. Silence again reigned, andMrs. Hill glanced at her boy and smiled. Encouraged, Jimmy returnedto the charge.

"Then why does the paper say it will?"

"For want of something else to say," replied Mr. Hill. "The airshipsand flying machines will play their part, of course, and it will be abig part, too. The real winning of the war must be done on the ground,however, after all. One thing this war has shown very clearly. Noone arm is all-powerful or all necessary in itself alone. Everybranch of the service of war must co-operate with another, if not withall the others. It is a regular business, this war game. I have readenough to see that. It is team-work that counts most in the bigmovements, and I expect that it is team-work that counts most allthe way through, in the detailed work as well."

Team-work! That had a familiar ring to Jimmy. Team-work was what thefootball coach had forever pumped into his young pupils. Team-work!Yes, Jimmy knew what that meant.

"I can give you a bit of news, Jimmy," added Mr. Hill. "If you are sointerested in the war in the air you will be glad to hear that the oldFrisbie place a few miles out west of the town is to be turned into anairdrome---a place where the flying men are to be taught to fly. Iexpect before the war is over we will be so accustomed to seeingaircraft above us that we will not take the trouble to look upward tosee one when it passes."

Jimmy's heart gave a great leap, and then seemed to stand still. Onlyonce, at the State Fair, had he seen a man fly. It had so touched hisimagination that the boy had scoured the papers and books in thepublic library ever since for something fresh to read on the subjectof aviation. As a result Jimmy had quite a workable knowledge ofwhat an aeroplane really was and the sort of work the flying menwere called upon to do at the front.

The Brighton boys were all keen on flying. What boys are not? Theirinterest had been stimulated particularly, however, by the news, theyear before, that Harry Corwin's big brother Will, an old Brighton boyof years past, had gone to France with the American flying squadronattached to the French Army in the field. True, Will was only anovice and the latest news of him from France told that he had not asyet actually flown a machine over the German lines, but he was atangible something in which the interest of the schoolboys could center.

An airdrome near the town! What wonders would be worked under his veryeyes, thought Jimmy. Flying was a thing that no one could hide behinda tall fence. Besides, there were no high fences around the Frisbieplace. Well Jimmy knew it. Its broad acres and wide open spaces werewell known to every boy at Brighton Academy, for within its boundarieswas the finest hill for coasting that could be found for miles. Inwinter-time, when the hillsides were deep with snow, Frisbie's slopesaw some of the merriest coasting parties that ever felt theexhilaration of the sudden dash downward as the bright runners skimmedthe hard, frosty surface. The long, level expanse of meadow that hadto be crossed before the hill was reached from the Frisbie mansionwould be an ideal place for an airdrome. Even Jimmy knew enough aboutairdromes to recognize that. He waited a moment at the table to takein fully the momentous fact that their own little town was to be acenter of activity with regard to aviation.

Then he dashed out to spread the news among his schoolfellows. Hisparticular chums were, like himself, boys whose homes were in the town.Shut out from the dormitory life, they had grouped themselves together,in no spirit of exclusiveness, but merely as good fellows who, althou

ghthey appreciated the love and kindness of the home folks, yet felt thatthey wanted to have as much of the spirit of dear old Brighton outsidethe Academy as inside.

Jimmy caught sight of Archie Fox---another of the out-boarding squad ofBrighton boys, and a special friend of Jimmy's---hurrying to the Academy.

"Great news for you, Arch!" shouted Jimmy as he joined his chum.

"Shoot!" directed Archie.

And Jimmy told the great news to the astonished and delighted boy.

"Gosh whillikens!" yelled Archie. "A real live hangar in staid oldBrighton! Can you beat it? My vote says the 'buddies' should gettogether and become fliers. Eh, what? The Brighton Escadrille! Oh,boy!"

Further down the street Dicky Mann and Joe Little, both in Jimmy'sclass at the Academy, and then Henry Benson, known to all and sundryas "Fat" Benson from his unusual size, joined the boys and heard forthe first time the stirring news.

It was truly an exciting morning at the Academy. The tidings of greatthings in store at no far distant future spread like wildfire. Of allthe boys, only two of those who lived in the town, Jimmy Hill and BobHaines, had heard of the project, and none of the regular boarders atthe school had heard the slightest suggestion of it. Bob Haineslived with his uncle in the largest residence in the town. What Bob'suncle did not know of what was going on was little. Beside, Bob wasthe envied recipient of a letter now and again from his father, thesenator, which frequently contained some real news of prospectivehappenings.

Bob held forth at length that memorable morning, and at noon time wasstill the center of an admiring group, who listened to his commentson all subjects with great respect and invariable attention. Bob wastall and well built; taller than any of the rest of his fellows excepttwo or three. He had a way of standing with his head thrown back andhis shoulders squared as he talked which gave him a commanding air.Few boys in the school ever thought of questioning his statements. Butthat day Bob was so carried away with his subject that he strayedfrom familiar ground.

"What sort of fellows are they going to train to fly?" asked JoeLittle, a shy boy who rarely contributed to the conversation. Joe'smother was a widow who had lived but few years in the town, havingmoved there to give her only boy such education as he could obtainbefore her small income was exhausted. Joe was never loud or boisterous,and while he took his part in games and sports, he was ever the firstone to start for his home. Being alone with his mother to such anextent, for they lived by themselves in a little cottage near theAcademy grounds, Joe had aged beyond his boy friends in many ways.No sign did he ever show, however, of self-assertiveness. His part indiscussions was seldom great, and usually consisted of a well-placedquery that voiced what each boy present had thought of asking, buthad been a moment too late.

Now Bob had no very clear idea just where the new flying material wasto come from. A habit of rarely showing himself at a loss for ananswer prompted him to reply: "From the men in the army."

"You're wrong, Bob," said Jimmy Hill. "Most of the flying men thatwill see actual service at the front will be boys like us. I haveread a dozen times that it is a boy's game---flying. Most of us arealmost old enough. One article I read said that lots of boys ofseventeen got into the flying corps in England. One writer saidthat he thought the fellows from eighteen to twenty were much thebest fliers. If that is so, and it takes some time to train fliers,some of us might be flying in France before the end of the war."

Bob was frankly skeptical. "I see you flying, Jimmy!" was his comment."You will have to grow some first.

"Wrong again," said Jimmy in all seriousness. "It's those of us thatdon't weigh a ton that are going to be the best sort for the flyingbusiness, and don't you forget it."

"Jimmy knows a lot about flying," volunteered Archie Fox. "He bonesit up all the time."

"I don't pretend to know much about it, but I am going to know morebefore that airdrome gets started," said Jimmy.

"That's right," said Joe Little quietly. "It won't hurt any of us toget a bit wiser as to what an aeroplane really is nowadays. Where doyou get the stuff to read, Jimmy?"

"Everywhere I can," answered Jimmy. "The weeklies and monthliesgenerally contain something on flying."

"My father can get us some good stuff," suggested Dicky Mann. Mr. Mann,senior, was the proprietor of the biggest store in the town; and whilehe did not exactly pretend to be a universal provider, he couldproduce most commodities if asked to do so. The store had a fairlyextensive book and magazine department, so Dicky's offer to enlistthe sympathies of his father promised to be of real use.

"I'll write to my brother Bill and get him to fire something over tous from France," said Harry Corwin. "There is no telling but what hecan put us on to some wrinkles that the people who write things forthe papers would never hear about."

"My aunt just wrote me a letter asking me what sort of a book I wantedfor my birthday," put in Fat Benson. "I will write to-day and tell herI want a book that will teach me to fly."

This raised a storm of laughter, for Henry Benson's stout figure bidfair to develop still further along lines of considerable girth, andthe very thought of Fat flying was highly humorous to his mates.

The little group broke up hurriedly as Bob looked at his watch and sawhow time was slipping away.

"Back to the grind, fellows!" he cried. "We'll have another talk-festlater on."

That random conversation was one day to bear splendid fruit. The seedshad been sown which were to blossom into the keenest interest in thereal, serious work of the mastery of the air. Live, sterling youngfellows were in the Brighton Academy. Some of them had declaredallegiance to the army, some to the navy, but now here was a stoutheartedbunch of boys that had decided they would give themselves to the studyof aeronautics, and lose no time about it.

The seven spent a thoughtful afternoon. It was hard indeed for anyone of them to focus attention on his lessons. The newness of theidea had to wear off first. After class hours they met again andwent off by themselves to a quiet spot on the cool, shady campus.Seated in a circle on the grass, they talked long and earnestly of waysand means for commencing their study of air-machines and airmensystematically.

"This," said Jimmy Hill with a sigh of pure satisfaction, "is team-work.My father said this morning that team-work counts most in this war.If our team-work is good we will get on all right."

Team-work it certainly proved to be. It was astonishing, as the dayspassed, how much of interest one or another of the seven could findthat had to do with the subject of flying. They took one other boyinto their counsels. Louis Deschamps was asked to join them and didso with alacrity, it seemed to lend an air of realism to their schemeto have the French boy in their number.

Dicky Mann's father had taken almost as great an interest in the ideaas had Dicky himself, and Mr. Mann's contributions were of the utmostvalue.

Days and weeks passed, as school-days and school-weeks will. Lookingback, we wonder sometimes how some of those interims of our waitingtime were bridged. The routine work of study and play had to be gonethrough with in spite of the preoccupation attendant on the art offlying, as studied from prosaic print. It was a wonder, in fact,that the little group from the boys of the Brighton Academy did nottire of the researches in books and periodicals. They learned much.Many of the articles were mere repetitions of something they had readbefore. Some of them were obviously written without a scrap oftechnical knowledge of the subject, and a few were absolutelymisleading or so overdrawn as to be worthless. The boys graduallycame to judge these on their merits, which was in itself a big stepforward.

The individual characteristics of the boys themselves began to show.Three of them were of a real mechanical bent. Jimmy Hill, Joe Littleand Louis Deschamps were in a class by themselves when it came to thedetails of aeroplane engines. Joe Little led them all. One night hegave the boys an explanation of the relation of weight to horsepowerin the internal-combustion engine. It was above the heads of some ofhis listen

ers. Fat Benson admitted as much in so many words.

"Where did you get all that, anyway?" asked Fat in open dismay.

"It's beyond me," admitted Dicky Mann.

"Who has been talking to you about internal combustion, anyway?"queried Bob Haines, whose technical knowledge was of no high order,but who hated to confess he was fogged.

"Well," said Joe quietly, "I got hold of that man Mullens that worksfor Swain's, the motor people. He worked in an aeroplane factory inFrance once, he says, for nearly a year. He does not know much aboutthe actual planes themselves, but he knows a lot about the Gnomeengine. He says he has invented an aeroplane engine that will lickthem all when he gets it right. He is not hard to get going, but hewon't stay on the point much. I have been at him half a dozen timesaltogether, but I wanted to get a few things quite clear in my headbefore I told you fellows."

The big airdrome that was to be placed on the Frisbie property graduallytook a sort of being, though everything about it seemed to progresswith maddening deliberation. Ground was broken for the buildings.Timber and lumber were delayed by Far Western strikes, but finally putin an appearance. A spur of railway line shot out to the site of thenew flying grounds. Then barracks and huge hangars---the latter tohouse the flying machines---began to take form.

At first no effort was made to keep the public from the scene of theactivity, but as time went on and things thereabouts took moretangible form, the new flying grounds were carefully fenced in, and aguard from the State National Guard was put on the gateways. So faronly construction men and contractors had been in evidence. Such fewactual army officers as were seen had to do with the preparation ofthe ground rather than with the Flying Corps itself. The closing ofthe grounds woke up the Brighton boys to the possibility of the factthat they might be shut out when flying really commenced. A councilof war immediately ensued.

"A lot of good it will have done us to have watched the thing get thisfar if, when the machines and the flying men come, we can't get beyondthe gates," said Harry Corwin.

"I don't see what is going to get us inside any quicker than any otherfellows that want to see the flying," commented Archie Fox dolefully.

"What we have got to get is some excuse to be in the thing some way,"declared Bob Haines. "If we could only think of some kind of job wecould get inside there---some sort of use we could be put to, it wouldbe a start in the right direction."

Cudgel their brains as they would, they could not see how it was to bedone, and they dispersed to think it over and meet on the morrow.

Help came from an unexpected source. After supper that night HarryCorwin happened to stay at home. Frequently he spent his eveningswith some of the fellows at the Academy, but he had discovered a bookwhich made some interesting comments on warping of aeroplane wings,and he stayed home to get the ideas through his head, so that hemight pass them on to the other boys. Mr. and Mrs. Corwin andHarry's sister, his senior by a few years, were seated in the livingroom, each intent on their reading, when the bell rang and the maidsoon thereafter ushered in a tall soldier, an officer in theAmerican Army. The gold leaf on his shoulder proclaimed him a major,and the wings on his collar showed Harry, at least, that he was oneof the Flying Corps.

The officer introduced himself as Major Phelps, and said he hadpromised Will Corwin, in France, that he would call on Will's folkswhen he came to supervise the new flying school at Brighton. Mr.Corwin greeted the major cordially, and after introducing Mrs. Corwinand Harry's sister Grace, presented Harry, with a remark that sentthe blood flying to the boy's face.

"Here, Major," said Mr. Corwin, "is one of the Flying Squadron ofthe Brighton Academy."

The major was frankly puzzled. "Have you a school of flying here,then?" he asked as he took Harry's hand.

"Not yet, sir," said Harry with some embarrassment.

"That is not fair, father," said Grace Corwin, who saw that Harry wasrather hurt at the joke. "The Brighton boys are very much interestedin aviation, and some time ago seven or eight of them banded togetherand have studied the subject as hard and as thoroughly as they could.See this "---and she reached for the book Harry had beenreading---"This is what they have been doing instead of something muchless useful. There is not one of them who is not hoping one day to bea flyer at the front, and they have waited for the starting of flyingat the new grounds with the greatest expectations. I don't think itis fair to make fun of them. If everyone in the country was as eagerto do his duty in this war it would be a splendid thing."

Grace was a fine-looking girl, with a handsome, intelligent face.When she talked like that, she made a picture good to look upon.Harry was surprised. Usually his sister took but little account ofhis activities. But this was different. With her own brother Willfighting in France, and another girl's brother Will a doctor in theAmerican Hospital at Neuilly, near Paris, Grace was heart and soulwith the Allies. Harry might have done much in other lines withoutattracting her attention, but his keenness to become a flier at thefront had appealed to her pride, and she felt deeply any attempt tobelittle the spirit that animated the boys, however remote might bethe possibility of their hopes being fulfilled.

Major Phelps listened to the enthusiastic, splendid, wholesome girlwith frank admiration in his eyes. Harry could not have had a betterchampion. First the major took the book. Glancing at it, he raisedhis brows. "Do you understand this?" he asked.

"I think so, sir," answered Harry.

"It is well worth reading," said the major as he laid it down. Thenhe stepped toward Harry and took his hand again. "Your sister isperfectly right, if your father will not mind my saying so. I havebeen attached to the British Flying Corps in France for a time, andI saw mere boys there who were pastmasters of scout work in the air.The game is one that cannot be begun too young, one almost might say.At least, the younger a boy begins to take an interest in it andreally study it, the better grasp he is likely to have of it. I amthoroughly in agreement with your sister that no one should discourageyour studies of flying, and if I can do anything to help while Ihappen to be in this part of the world, please let me know. You looklike your brother Will, and if you one day get to be the flier thathe is, as there is no reason in the world you should not do, youwill be worth having in any flying unit."

Harry was struck dumb for the moment. This was the first tangibleevidence that the plans of the boys were really to bear fruit, afterall. He stammered a sort of husky "Thank you," and was relieved tofind that Major Phelps mention of Will had drawn the attention fromeverything else for the moment. The Corwins had to hear all aboutthe older boy, whose letters contained little except the mostinteresting commonplaces.

The major, it is true, added but little detail of Will's doings,except to tell them that he was a full-fledged flying man and wasdoing his air work steadily and most satisfactorily. His quietpraise of Will brought a flush of pride to Grace's cheek, and themajor wished he knew of more to tell her about her brother, as itwas a pleasure to talk to so charming and attentive a listener.

At last he rose to take his departure, and the Corwins were loud intheir demands that he should come and see them often. As the majorstepped down from the piazza Harry grasped his courage in both handsand said:

"Major Phelps, may I ask you a question?"

"Certainly," said the major genially. "What is it?"

"Well, sir," began Harry, "we Brighton boys have been wondering howwe can get inside the new airdrome. Summer vacation is coming, andwe could all---the eight of us, in our crowd---arrange to stay hereafter the term closes. We want to be allowed inside the grounds, andto have a chance to learn something practical. We would do anythingand everything we were told to do, sir."

"Hum," said the major. "Let me think. You boys can be mighty usefulin lots of ways. I'll tell you what I will do. Find out whether ornot your friends would care to get some sort of regular uniform andtake on regular work and I will speak to the colonel about it whenhe comes. I think he will be here to-morr

ow or next day. Thingsare getting in shape, and we will be at work in earnest soon. Thecolonel is a very nice man, and when he hears that you boys are soeager to get into the game maybe he will not object to your beingattached regularly to the airdrome for a while. You might findthat the work was no more exciting than running errands or somethinglike that. Are you all of pretty good size? There might be someuseful things to do now and again that would take muscle."

"I am about the same size as most of the rest," replied Harry.

"You look as if you could do quite a lot," laughed the major, as hewalked down the path, leaving behind him a boy who was nearer theseventh heaven of delight than he had ever been before.

Before the end of the week the colonel came. The boys had their planscut and dried. Harry's sister Grace had taken an unusual interestin them, and had advised them wisely as to uniforms. Major Phelpsseemed interested in them, too, in a way. At least, he called at theCorwin home more than once and talked to Grace about that andother things.

Colonel Marker was rather grizzled and of an almost forbidding appearanceto the boys. They feared him whole-heartedly the moment they laideyes on him. His voice was gruff and he had a habit of wrinkling hisbrows that had at times struck terror into older hearts than those ofthe Brighton boys. But he was a very kindly man, nevertheless, inspite of his bluff exterior.

Major Phelps told him about the eight lads, borrowing, perhaps, someof Grace Corwin's enthusiasm for the moment, and the colonel wasfavorably impressed from the start with what he called "a mightyfine spirit." He thumped his fist on the table at which he satwhen the major told him of the boys and their hopes, and saidexplosively:

"Wish there were more like them in every town out here. We are toofar from the actual scene of war. Some people who are a lot olderand who should have a lot more realization of what we need and musthave before this war is over might take a good lesson from suchyoungsters. I would like to see them."

That settled it. When the colonel took a thing up he adopted itabsolutely. In a day or so he would be talking of the little bandof Brighton boys as if the original project had been his from thevery start. "Boy aviation corps? Why not. Good for them. Can findthem plenty to do. When they get to the right size we can put 'emin the service. Why not? Good to start young. Of course it is.Splendid idea. Must be good stuff in 'em. Of course there is.Send 'em to me. Why not?"

Thus, before the boys were brought under the colonel's eye he hadreally talked himself into an acceptance of the major's idea. Themorning he saw them, a little group of very eager and anxiousfaces---bright, intelligent, fine faces they were, too---he saidwithout delay: "I have a use for you boys. I have thought ofsomething for you to do. Get some sort of rig so I can tell you whenI see you, and come to me again and I will set you at work."

Not long after, vacation time had come, and with it the new uniforms,in neat, unpretentious khaki. Garbed in their new feathers and"all their war paint," as Mr. Mann called it, they reported at theairdrome main gate just as the first big wooden crate came past ona giant truck. Inside that case, every boy of them knew, wasthe first flying machine to reach the new grounds. They felt itan omen.

A few minutes later they were in the austere presence of ColonelMarker, who was frankly pleased with their soldierly appearanceand the quiet common-sense of their uniforms, which bore no fancyadditions of any sort.

Grace Corwin had seen to that, though more than one furtive suggestionfrom one boy or another had to be overruled. Bob Haines thought theletters "B.B." on the shoulders would vastly help the effect. Crossedflags on the right sleeve would have suited Dicky Mann better. FatBenson's voice was raised for brass buttons. Jimmy Hill'spretensions ran to a gilt aeroplane propellor for the front of eachsoft khaki hat. But Grace was firm. "No folderols," was herdictum. They were banded together for work, not for show. Letadditions come as the fruit of service, if at all. And she had herway. Grace usually did.

"Glad to see you, boys. You will report to the sergeant-major, whowill take a list of your names, assign you your duties, and arrangeyour hours of work. I am afraid there is no congressional grantfrom which to reward you for your services by a money payment, butif you do your work well, such as it is, I will keep an eye on youand see if I cannot put you in the way of learning as much as youcan about the air service."

That was their beginning. They saluted, every one, turned smartlyand filed out. Bob Haines, the tallest of the group and the acknowledgedleader, was the only one to answer the colonel. Bob said, "Thank you,sir," as he saluted. They looked so strong and full of life and hopethat the tears welled to the colonel's eyes as he watched them trampout of his room. He had seen much war, had the colonel. "It's ashame that such lads will have to pay the great price, many of 'em,"he sighed, "before the Hun is brought to his knees. But it's a finething to be a boy." The colonel rose stiffly and sighed. "I wouldgive a lot to be in their shoes, with all the hardship and horrorthat may lie in front of them if this war keeps on long enough," hemused to himself. "It's a fine thing to be a boy."

Out went the eight Brighton boys to the sergeant-major, their workbegun. They too felt it a fine thing to be boys, though their feelingwas just unconscious, natural, effervescent---the sparkle of the realwine of youth and health and clean, brave spirit.