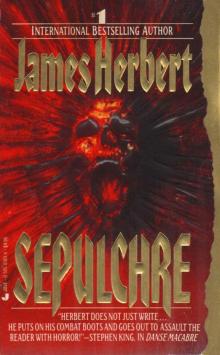

Sepulchre

James Herbert

THE FACE OF EVIL

Halloran stepped back, horrified at the countenance that stared up at him.

The skin was withered and deeply rutted, like wrinkled leather left in the sun; and its coloring, too, was of old leather, except where there were festering scabs that glinted under the flashlight. Most alarming of all were the eyes. They were huge, lidless, bulging from the skull as if barely contained within their sockets; the pupils were cloudy, a fine membrane coating them, and the area around them that should have been white was yellow and patchworked with tiny veins.

"It's you," came the sibilant whisper . . .

SEPULCHRE

"Herbert skillfully weaves industrial espionage, terrorism, mythology, and supernatural horror into a fast-moving and well-written narrative. Attention to character, riveting suspense, and a satisfyingly chilling conclusion show Herbert once again to be a master of the genre!"

—Library Journal

Praise for James Herbert's

previous novels:

"Scary, engaging . . . When Herbert's beautifully orchestrated crescendo of suspense peaks, the scares have the genuine shivers-down-the-back-of-the-neck quality of Shirley Jackson or M. R. James."

—The Washington Post

"Fascinating . . . a dream of the human soul's immortality."

—The New York Times

Novels by James Herbert

THE RATS

LAIR

DOMAIN

THE FOG

THE SURVIVOR

FLUKE

THE SPEAR

THE DARK

THE JONAH

SHRINE

MOON

THE MAGIC COTTAGE

SEPULCHRE

This Jove book contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. It has been completely reset in a typeface designed for easy reading, and was printed from new film.

SEPULCHRE

A Jove Book/published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

G. P. Putnam's Sons edition/July 1988 Jove edition/August 1989

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1987 by James Herbert. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

ISBN: 0-515-10101-X

Jove Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

The name "JOVE" and the "J" logo

are trademarks belonging to Jove Publications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 987654321

CONTENTS

The Sumerians

1 MORNING DUES

2 ACHILLES 'SHIELD

3 MAGMA

4 THE NEED FOR SECRECY

5 THE WHITE ROOM

6 FELIX KLINE

7 KLINE'S PREMONITION

8 BODYGUARDS

9 ENTICEMENT 63

10 INTRUDER 65

11 A DANGEROUS ENCOUNTER

Monk A PILGRIM'S PROGRESS

12 NEATH

13 CONVERSATION WITH CORA

14 ROOMS AND CORRIDORS

15 A STROLLING MAN

16 A DIFFERENT KLINE

17 A DREAM OF ANOTHER TIME

18 UNHOLY COMMUNION

19 CORA'S NEEDS

20 ABDUCTION

21 BENEATH THE LAKE

22 FOOD FOR DOGS

23 THE LODGE HOUSE

Janusz Palusinski A PEASANT'S SURVIVAL

24 CORAS ANGUISH

25 LAKE LIGHT

26 AN ANCIENT CULTURE

27 A DREAM AND BETRAYAL

28 HALLORAN

29 RECONNOITER

30 RETRIBUTION IN DARKNESS

Khayed and Daoud DISPLACED AND FOUND

31 RETURN TO NEATH

32 A SHEDDING OF SKIN

33 INSIDE THE LODGE

34 INTO THE PIT

35 THE WAITING GAME

36 A ROOM OF MEMORIES

37 JOURNEY AROUND THE LAKE

38 THE KEEPER

39 A TERROR UNLEASHED

40 A TERRIBLE DISCOVERY

41 THINGS FROM THE LAKE

42 SEPULCHRE

43 THE OPEN GATES

44 A SACRIFICE

45 NETHERWORLD RISING

46 TOWARD DESTRUCTION

47 ACROSS THE COURTYARD

48 BLOOD RITES

49 RETURN TO THE DEATH HUT

50 SHADOWS AND IMAGININGS

51 END OF THE STORM

52 THE BATTLE OVER

Serpent

There are no absolutes . . .

'And the Lord God said unto

the serpent, Because thou hast done this,

thou art cursed above all cattle, and

above every beast of the field; upon thy

belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat

all the days of thy life.'

Genesis 3:14

The Sumerians

Three thousand years before the birth of Christ, the first real moves toward civilization emerged from southern Mesopotamia, around the lower reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Because the land was between two rivers—Sumer—the people there were called Sumerians.

Their ethnic origins have never been explained.

This race of people made three important contributions toward our advancement—four if you count the establishment of firmly governed communities.

The first two were these:

The measurement of time in hours, days, and months; and astrology, the study of the stars' influences, which eventually led to the science of astronomy.

But the third was most important of all, for the Sumerian high priests discovered a way of making man immortal. Not by eternally binding his spirit to its earthly shell, but by preserving his knowledge. These high priests devised the written word, and nothing invented since has had a greater effect on mankind's progression.

Yet little is known of these people themselves.

By 2400 B.C., they had been swallowed up by surrounding, less enlightened tribes, who absorbed the Sumerian culture and spread it to other lands, other nations.

So although their achievements survived, the Sumerians' early history did not. For the kings, the princes, and the high priests destroyed or hid all such records.

Possibly they had good reason.

1

MORNING DUES

The man was smiling. Halloran was smiling and he shouldn't have been.

He should have been scared—bowel-loosening scared. But he didn't appear to be. He seemed . . . he seemed almost amused. Too calm for a sane man. As if the two Armalites and the Webley .38 aimed at his chest were of no concern at all.

Well, that wisp of a smile on his unshaven face would spirit itself away soon enough. This "eejit's" reckoning was coming, sure, and it was a terrible unholy one.

McGuillig waved his revolver toward the van parked in the shadows of trees just off the roadside.

"Your man's in there."

The harshness of his tone made it clear he held scant patience with Halloran's manner.

"And your money's here," Halloran replied, nudging the bulky leather case on the ground with his foot.

McGuillig watched him coolly. When he'd spoken on the phone to the operative, he'd detected a trace of Irish in Halloran's voice, the merest, occasional lilt. But no, he was pure Brit now, no doubt at all.

"Then we'll get to it," McGuillig said.

As he spoke, rays from the early-morning sun broke through, shifting some of the grayness from the hillsides. The trees nearby dripped dampness, and the long grass stooped with fresh-fallen rain. But the air was alre

ady sharp and clear, unlike, as McGuillig would have it, the unclean air of the North. Free air. Uncontaminated by Brits and Prods. A mile away, across the border, the land was cancered. The Irishman regarded the weapon he held as the surgeon's scalpel.

Just as McGuillig, brigade commander of D Company,

Second Battalion of the Provisional IRA, watched him, so Halloran returned his gaze, neither man moving.

Then Halloran said: "Let's see our client first."

A pause before McGuillig nodded to one of his companions, a youth who had killed twice in the name of Free Ireland and who was not yet nineteen. He balanced the butt of the Armalite against his hip, barrel threatening the very sky, and strolled to the van. He had to press hard on the handle before the back door would open.

"Give him a hand," McGuillig said to the other Provo on his left. "Don't worry about these two: they'll not be moving." He thumbed back the Webley's hammer, its click a warning in the still air.

All the same, this second companion, older and more easily frightened than his leader, kept his rifle pointed at the two Englishmen as he walked over to the van.

"We had to dose up your man," McGuillig told Halloran. "To keep him quiet, y'understand. He'll be right as rain by tomorrow."

Halloran said nothing.

The back door was open fully now and a slumped figure could be seen inside. The older Provo reluctantly hung his rifle over one shoulder and reached inside the van along with the youth. They drew the figure toward themselves, lifting it out.

"Bring him over, lads. Lay him on the ground behind me," their commander ordered. To Halloran: "I'm thinking I'd like to see that money."

Halloran nodded. "I'd like my client examined."

McGuillig's tone was accommodating. "That's reasonable. Come ahead."

With a casual flick of his hand, Halloran beckoned the heavyset man who was leaning against their rented car twenty yards away. The man unfolded his arms and approached. Not once did Halloran take his eyes off the IRA leader.

The heavyset man strode past Halloran, then McGuillig. He knelt beside the prone figure, the Irish youth crouching with him.

He gave no indication, made no gesture.

"The money," McGuillig reminded.

Halloran slowly sank down, both hands reaching for the leather case in front of him. He sprung the two clasps.

His man looked back at him. No indication, no signal.

Halloran smiled, and McGuillig suddenly realized that it was he himself who was in mortal danger. When Halloran quietly said—when he breathed—"Jesus, Mary . . ." McGuillig thought he heard that lilt once more.

Halloran's hands were inside the case.

When they reappeared an instant later, they were holding a snub-nosed submachine gun.

McGuillig hadn't even begun to squeeze the .38's trigger before the first bullet from the Heckler & Koch had imploded most of his nose and lodged in the back of his skull. And the other Provo hadn't even started to rise before blood was blocking his throat and gushing through the hole torn by the second bullet. And the Irish youth was still crouching with no further thoughts as the third bullet sped through his head to burst from his right temple.

Halloran switched the submachine gun to automatic as he rose, sure there were no others lurking among the trees, but ever careful, chancing nothing.

He allowed five seconds to pass before relaxing. His companion, who had thrown himself to the ground the moment he saw Halloran smile, waited just a little longer.

2

ACHILLES' SHIELD

The sign for Achilles' Shield was as discreet as its business: a brass plaque against rough brick mounted inside a doorway, the shiny plate no more than eight-by-four inches, a small right-angled triangle at one end as the company logo. That logo represented the shield that the Greek hero Achilles, if he'd been wiser, would have worn over his heel, his body's only vulnerable part, when riding into battle. The name with its simple symbol, was the only fanciful thing about the organization.

Situated east of St. Katharine's Dock, with its opulent yacht basin and hotel, the offices of Achilles' Shield were in one of the many abandoned wharfside warehouses that had been gutted and refurbished in a development that had brought trendy shops, offices, and "old style" pubs to lie incongruously beneath the gothic shadow of Tower Bridge. The company plaque was difficult to locate. To spot it, you had to know where it was. To know, you had to be invited.

The two men sitting in the fourth-floor office—a large, capacious room, because space wasn't at a premium in these converted warehouses—had been invited. One of them had been invited many times over the past six years.

He was Alexander Buchanan, a suitably sturdy name for an underwriter whose firm, Acom Buchanan Limited, had a "box" on the floor of Lloyd's of London and company offices near Fenchurch Street. Acorn Buchanan's speciality was K & R insurance. Kidnap and Ransom.

The person with him was his client, Henry Quinn-Reece, chief executive and deputy chairman of the Magma Corporation PLC. He looked ill at ease, even though the leather sofa on which he sat was designed for maximum comfort. Perhaps he did not enjoy the scrutiny he was under.

The scrutineers were three, and they were directors of Achilles' Shield. None of these men did or said anything to relax their prospective client. In fact, that was the last thing they wanted: they liked their interviewees to be on edge, and sharper because of it.

The one behind the large leather-topped desk, who was in charge of the meeting, was Gerald Snaith, Shield's managing director, officially titled Controller. He was forty-nine years old, a former major in the SAS, and had trained soldiers, British and foreign, all over the world. His main service action had been in Oman, his exploits largely unknown to the public because, after all, that particular conflict—or more accurately, the British Army's participation in it—had never been recognized officially. A short man, and stocky, his hair a slow-graying ginger, Snaith looked every inch a fighting man which, in truth, he still was.

In a straight-backed chair to the side of the Controller's desk sat Charles Mather, a Member of the Order of the British Empire, a keen-eyed man of sixty-two years. Those keen eyes often held a glint of inner amusement, as though Mather found it impossible to treat life too seriously all the time, despite the grim nature of the business he was in. Introduced to clients as Shield's Planner, personnel within the organization preferred to call him the Hatcher. He was tall, thin, and ramrod, but forced to use a cane for walking because of a severe leg wound received in Aden during the latter stages of that "low-intensity" campaign. A jeep in which he was traveling had been blown off the road by a land mine. Only his fortitude and an already exemplary military career had allowed him to return to his beloved army, sporting concealed scars and a rather heroic limp; unfortunately a sniper's bullet had torn tendons in that same leg many years later when he had been General Officer Commanding and Director of Operations in Ulster— hence the stick and early retirement from the British Army.

The only non-English name among a very English assemblage was that of Dieter Stuhr, German-born and at one time a member of the Bundeskriminalamt, an organization within the German police force responsible to the federal government for the monitoring of terrorists and anarchist groups. Stuhr sat alongside Snaith at the desk. Younger than his two colleagues and four years divorced, his body was not in the same lean condition: a developing paunch was beginning to put lower shirt buttons under strain, and his hairline had receded well beyond the point of no return. He was an earnest, overanxious man, but supreme at organizing movement, finances, timetables, and weaponry for any given operation, no matter what the difficulties, be they dealing with the authorities in other countries (particularly certain police chiefs and high-ranking officials who were not above collusion with kidnappers and terrorists) or arranging "minimum-risk" life-styles for fee-paying "targets." Within the company he was known very properly as the Organizer.

He bore an impressive scar on his face that might well

have been a sword-scythed wound, perhaps the symbol of machoism so proudly worn by dueling Heidelberg students before and during Herr Hitler's rapid rise to infamy; but Stuhr was not of that era and the mutilation was nothing so foolishly valiant. It was no more than a deep, curving cut received in his childhood while falling off his bicycle after freewheeling down a too-steep hill outside his hometown of Schleiz. A truck driver ahead of him had been naturally cautious about crossing the junction at the bottom of the hill and Stuhr, an eleven-year-old schoolboy at the time, had neglected to pull on his brakes until it was too late. The bicycle had gone beneath the truck, while the boy had taken a different route around the tailboard's corner catching his face as he scraped by.

The scar stretched down from his left temple, and curved into his mouth, a hockey-stick motif that made his smile rise up the side of his head. He tried not to smile too much.

Gerald Snaith was speaking: "You understand that we'd need a complete dossier on your man's background and current life-style?"

Quinn-Reece nodded. "We'll supply what we can."

"And we'd have to know exactly how valuable he is to your corporation."

"He's indispensable," the deputy chairman replied instantly.

"Now that is unusual." Charles Mather scratched the inside of one ankle with his walking stick. "Invaluable, I can appreciate. But indispensable? I didn't realize such an animal existed in today's world of commerce."

Alexander Buchanan, sitting by his client on the leather sofa, said, "The size of the insurance cover will indicate to you just how indispensable our target is."

"Would you care to reveal precisely what the figure is at this stage of the proceedings?"

The question was put mildly enough, but the underwriter had no doubts that a proper answer was required. He looked directly at Quinn-Reece, who bowed assent.

"Our man is insured for fifty million pounds," said Buchanan.

Dieter Stuhr dropped his pen on the floor. Although equally surprised, Snaith and Mather did not so much as glance at each other.