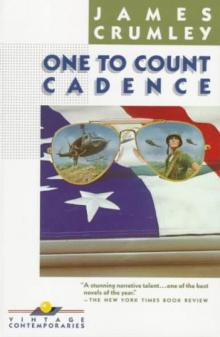

One to Count Cadence

James Crumley

One to Count Cadence

by James Crumley

Back Cover:

“James Crumley is the James Jones of Vietnam.” — Chicago Sun-Times

The time: late summer, 1962. The place: Clark Air Force Base, the Philippines. Sergeant Jacob “Slag” Krummel, a scholar by intent but a warrior by breeding, assumes command of the 721st Communication Security Detachment, an unsoldierly crew of bored, rebellious, whoring, foul-mouthed, drunken enlistees. Surviving military absurdities reminiscent of those in CATCH 22 only to be shipped clandestinely to Vietnam, Krummel’s band confront their worst fears while finally losing faith in America and its myths.

Powerful, scathingly funny and eloquent, ONE TO COUNT CADENCE is a triumphant novel about manhood, anger, war, and lies.

“A brawling, romantic novel about the hell of war, the value of friendship, the difficulties of loving and how to be a man despite the price of it all.” —Washington Post

“A gutting, eloquent first novel.” — Kirkus Reviews

“A compelling study of the gratuitous violence in men… carefully molded, without a slack line, a fuzzy character or blurred incident.” — The New York Times

First vintage contemporaries edition, June 1987

Copyright © 1969 by James Crumley

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by

Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in

Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published, in hardcover, by Random House in 1969.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Crumley, James, 1939-

One to count cadence.

(Vintage contemporaries)

I. Title.

PS3553.R7805 1987 813’.54 86-40468

ISBN 0-394-73559-5

Front page photo copyright © 1984 by Lee Nye

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

For my Mother and Father

and for Charlie

It was written I should be loyal to the nightmare of my choice.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

And I will call for a sword against him

throughout all my mountains, saith the

Lord: Every man’s sword shall be against

his brother.

Thus will I magnify myself, and sanctify

myself; and I will be known in the eyes

of many nations, and they shall know that

I am the Lord.

Ezekiel 38:21,23

Fuck ‘em all but nine —

Six for pallbearers,

Two for roadguards,

And one to count cadence.

Old Army Prayer

Historical Preface

It’s funny how stories get around. Just the other day Captain Gallard mentioned that one about the car. He hadn’t spoken for several minutes, but had sat, staring out my window toward the sixteenth green running his fingers through his curly hair. When he finally spoke, his voice was low, drifting far from the Philippines, all the way back to Iowa and his childhood, as he told me about the mythic automobile of his youth.

You know the story: the car, the big, fancy one you’ve always wanted and dreamed about, is for sale in a nearby city (always the city) for twenty-five dollars. They always tell that part first, as they told Gallard about this Lincoln in Des Moines. Then the eternal catch: an insurance salesman died in the car on some deserted road; died, then rotted, and the stench has seeped into the very metal. “And you know how death stinks,” he said to me, hands in his hair again, those hands (farmer’s hands, short and flat and strong, the tips of the middle two fingers on the right hand pinched off in a corn picker long ago), not at all the hands of a bone surgeon.

“I even saved the money,” he said with a wistful smile. “But I didn’t go to Des Moines. I don’t know why. It wasn’t the stink so much — no one would smell it but me as I roared up and down those gravel roads at night — but I couldn’t figure out how to get a girl in it, and you know cars are no good without girls. So I didn’t go,” he said, leaning back and chuckling. “Didn’t get the girl I had in mind either. At least not then.” He laughed again, smiled, then let his eyes wander back to the golf course and the two girls working on the green a short way down the hill across the road. The two were short, stocky mountain girls, Benguet Igorots, hips wrapped in many skirts and feet bound in oversized tennis shoes. They resembled those foolish and energetic dolls with weighted bases which when hit always swing up for another punch. But that wasn’t what I saw reflected in his eyes, not them, no, nor the bright green fairway fringed in dark pine, nor the city of Baguio misty and lost in the distance, none of these, but the long delicate snout of that mythic Lincoln.

In my not-so-distant youth the car was a Cadillac for one hundred dollars (even dreams are subject to inflation, I suppose) in San Antonio. A doctor, so the story went, had driven into the nearby cedar hills, then blasted a neat hole ringed with brain tissue through the top. I also dreamed, and also failed to follow, though not for so sensible a reason as Gallard. I was simply afraid it wasn’t true, and I certainly didn’t want to find out. I still hear of the car, though, as I’m sure you do. A Thunderbird in Los Angeles. A Corvette in Atlanta. A Jaguar in Boston. The cities, the cars change, but not those dusty boys in small towns, nor the dream. I’m sure of that; but no longer am I certain if we dream of the power and beauty of the machine or of the stink. Perhaps, and some say for sure, they are the same, but I don’t know. I just know the dream is real. Somewhere back in America grown men — doctors, lawyers, corporation chiefs — waste their fluid into the metal, decay and drip, drip, decay and fall, so you and I might dream — and be fooled into a nightmare of death and a cold wind over an open grave.

* * *

Gallard doesn’t care for me to talk like that, and when I told him how I felt about the dream car, he accused me of seeing all myths, thus God, as a conspiracy. When I answered “Certainly,” he accused me of a lack of seriousness. I reminded him that only the day before he had said I was too serious. He maintained that both accusations were valid. “Do you see evil everywhere,” he then asked, “or just reflect it?” (I remember Joe Morning asking me the same question once.)

Gallard cares for me, tends my mending arm and leg, carefully X-raying the leg once a week to check the pin. He claims the X-rays are really a plot to sterilize me, and I agree. But all this time he is really searching for another wound, a festering, dripping sore he thinks he smells. He hasn’t discovered it yet; but I’ll tell him someday. Like a sly old coyote around poisoned meat, he circles, retreats, holds his hunger. But soon the blood and flesh will be too much in his nose, and he must eat or go mad. Maggots purify an open wound, or so I’m told, and I don’t suppose I’ll really be well until the day Gallard eats the blood of my friend, Joe Morning, on these pages he gave me to record upon. “Therapeutic,” Gallard calls it. “Madness,” say I. But he is a doctor in the full sense of the word and he cares for wounds.

* * *

He smelled it quickly, perhaps even that first day I arrived at the Air Force hospital on Camp John Hay near Baguio. I don’t recall very much about the Med-evac flight from Vietnam — a bulky pain in my whole right side, a forest of gleaming needles, a constant plain of white faces. Then the plane approached the island of Luzon. At first the land was a speck, then a dot, then it grew into a disturbing blot on the pure surface of the ocean, a green-black imperfection in a blue universe. Soon it became an eruption, a timeless monster raising itself painfully from the silent depths of the Mindanao Trench, slime oozing down its stee

ply ridged back, circled in a froth of white where the sea boiled at contact. Closer, I felt the aged beast must reach up for the plane and brush it away like a troublesome gnat, and I was afraid, again, choked and blinded by fear, but as suddenly as it came, the fright disappeared, the world tumbled back to its rightful place. Slime grew back to thick jungle, and froth eased into restless waves napping at the mountains’ feet, and I… and the sleeper back to his grave.

Again awake as the plane approached Baguio, I glimpsed the stark arrogant mountains tripping and falling among themselves, tumbling into the waiting, self-righteous valleys, and then the soft plateau resting above the gigantic disorder. Everything spoke peace: the quiet green fairways trimmed out of the deep black of a tropical evergreen forest; the thousand dazzling blue-eyed swimming pools winking and glittering among color-dazed gardens and quiet homes.

But I wasn’t fooled. I still crouched in a radio van where grenades had scattered death like flowers; still hugged a ragged, skinny old man with blood blossoms adorning his chest. Like all warriors come home, I wasn’t sure where or when the fighting stopped, nor did I know the difference between night and day. Then eyes, coal-black and curious above a patient green mask, said, “Take it easy, son.” And so, for the moment, I submitted.

Many drug-weary days later, while I was still silent, Gallard came to ask after me. When I didn’t answer, he raised his eyebrows almost to the black curls drifting over his short, square forehead, asking again with his face. I nodded toward the casts on my arm and leg, toward the traction apparatus, and shrugged as best I could. He shook his head slightly as if to say, “Okay. Take it easy. I’ll be back another time.” A wise man, I thought, as he left.

More days with my eyes shutting out bare walls the color of clabbered milk, off-white, way off. The sunlight, rich and golden at the window, ran like rancid butter on those walls. My eyes closed often in self-defense, but found little peace in the darkness. Instead there were the visions, the dreams of a drunk sleeping in the chewing-gum filth of an all-night movie house, slipping in and out of scattered light and darkness until the shadows of his mind match, in a clever and evil way, the shadows on the screen. When he leaves, if ever, he has no memory of sleep. I had only the blank, white faces of false concern.

I ate the hospital’s surprisingly good food, submitted to the daily rituals of bath and bed-change, took their shots when they gave them, and endured in painful silence when they didn’t. “Is man such a stranger to agony that he must hunt for the Garden with a needle,” I say to the two nurses who drug me, Lt. Light and Lt. Hewitt. One laughs; the other thinks it is a famous quotation. Lt. Hewitt once said to an orderly at my door, “Battle fatigue,” and shook her hollow head. I laughed, an obscene, barking bellow. Lt. Hewitt, or Bones as she is known, smirked and quickly left. To tattle, I supposed. Regulations permit only Death and doctors above the rank of captain to laugh in this hospital.

Gallard came soon afterward and asked after me again. Silence had begun to bore me, but I wasn’t ready to talk yet. I wanted him to really want to know, so I said:

“Curious instruments aren’t the keys to Heaven, sir, nor for that matter, to my heart, either.”

“They, of course, weren’t meant to be,” he answered as he exited.

I laughed again, softer, and rang for the nurse. She raised my bed, but not quite high enough for me to see out my window comfortably. I lifted my body and a sudden wave of black discs floated at me. My head seemed airborne also, and the discs enlarged and drifted closer, then suddenly covered my eyes with a quick bright shock and I fainted.

Climbing up from the faint, more symbolically than physically, I quietly labored out of the sea of self-pity. My nose filled with the smell of fresh-cut grass, heavy and a bit too sweet, like watermelon, and the tart needles of pine, and the unmistakable mixture of make-up, sweat and perfume which meant woman. I focused on the blue, sweetly wrinkled eyes above mine.

“Hello, lovely,” I said, and touched her cheek. She blushed, her face like a rose nestled among her pale short hair. Lt. Light had a large body, but her face was a small, timid oval above it. She was small breasted, but perfect in the legs and hips. I hadn’t noticed before. She always hunched forward as if afraid her height might offend, and this small touch made her uniform seem less than the armor the other nurses wore.

“It seems you’re all right,” she said.

“I suppose the script calls for me to say, ‘Well, you’re pretty much all right yourself,’ and you are, in spite of the script, all right.”

“What do you want?”

“A cigarette?” I asked, and she gave me one and a light.

“Anything else?” she asked with the match cupped in her hand. “And if you say what the script calls for, I’ll bust your head.”

“It might be worth it.”

“It might,” she chuckled. She had sounded as if she really did want to know if I wanted anything else.

“You might stay and talk.”

“I can’t.”

“Not right now?”

“Not anytime. You’re an evil-minded enlisted man and I’m an officer and a gentleman,” she said with a bit of a smile. But then back to business: “You sure you’re all right?” She turned to leave as I nodded, and the hesitant way she carried her head struck me again. I wanted to straighten that back and lift that delicate face to the sun.

“One more thing,” I said.

“Yes?” she asked very solemnly. She could change so quickly. Like all defenseless things, she was too ready to be hurt.

“Your name?”

She smiled again, and then did it perfectly, never thinking Lt. Light would be enough. “Abigail Light.”

“Abby?”

“No.”

“Gail?”

“No. Abigail,” she said with a flip of her head, smiled again as if pleased by the sound of her name, then left. She had spoken her name in an old-fashioned way, musically important and not to be cheapened by a nickname, a name from a time when names mattered. Abigail Light. How much nicer than mine, I thought, mine which resembled an ominous rumble of thunder on a spring day. Jacob Slagsted Krummel. Slag Krummel.

I lay back in bed. My body, so lately and violently taught its vulnerability, forgot the pain, the violation. I stretched against the aches and pains of inactivity, scratched some of the smaller scabs on my right side, and decided I would live after all.

I examined my surroundings: my room; those sour walls; an uninviting porcelain-enamel framed bed, complete with an array of mechanical devices to push, pull, twist and turn, so that it might have been a place to get sick rather than well; two windows on the west wall, raised halfway and partly covered by age-yellowed roller shades, with panes of glass too clean to be less than sharp.

Out the windows is another story. In the distance sits the city of Baguio, summer capital of the Philippines, a multi-colored maze spread over half a dozen soft hills. Much nearer, lodged at the edge of a rise, is the Halfway House, a low and massive log building with an umbrella-spotted terrace slightly behind the ninth green. The tenth and eleventh fairways are across the road to the left, but I can’t see them, nor the twelfth, and only the back edge of the thirteenth green because all this is hidden by the rise on which the fourteenth tee sits. The fourteenth fairway is straight with a slight down-slope for two hundred yards, then the plane of the land tilts left for the next one hundred yards just where a well-hit slice will run downhill into the evergreen rain-forest mixture of rough. Then the fairway is level for another thirty yards to where the raised green is banked against the side of the hill with two small traps at the fore-lip. (I once drove the right-hand trap with a good drive and lots of downhill run, but Morning thought I had paid my caddie to drop the ball there. He always was a hard man to convince.) There is a road about twenty yards above the green, and a graveled path on this side of the road leading directly toward my window. The path forks between the road and the hospital, one fork leading toward the hospital

past my window, and the other toward the fifteenth tee off to the right. No one seems to walk toward my window, though.

My nostalgic lingering over the view was not without reason. There had been times when that small golf course had been our only refuge. We would come up when the heat and debaucheries of the plain had clogged our spirits, up to the mountains, to the sun and the afternoon rains. Cool air and solitude, fresh vegetables and virtue, golf and moderation, and the mountains stretching toward the sky. These things had brought peace to us then — but I wondered if they could pacify me now, now that I was alone with my memory, my history, now pinned with a wing I couldn’t carry.

Less than three months before, Cagle, Novotny, Morning and I had stood on that very circle of green which so occupied me when I saw it again, stood healthy and laughing as the sun ate the morning mists. And as I thought of them, the sudden life in my veins became quick guilt, and all I had to do to see them again was close my eyes.

Black and white, black and white, stark black and white. A negative world undeveloped by dawn. A roar of all sounds lashed into one and no single cry can lift its pleading arm above the clamor. Novotny’s healthy tan now blasted gray, his fatigues still starched, but he has a crazy black part through his stiff white hair. Cagle, small hairy body dancing in skivvy shorts, jerk, step, jerk, jerk, as blood spurts from his chest. And Joe Morning, Joe Morning, his strong length folding forward in a quick nervous bow as if someone important had just ended his life.

I opened my eyes and they were gone, and they were there, and there was not a thing I could do about it. I slept.

* * *

A nurse and a Filipino orderly woke me at ten for a bed-change and a whore’s bath. They managed to do it without making me pass out from the pain. The clean sheets were stiff and cool against my back, and the bath had left me feeling clean for a change. I might be clean, but my right leg, after two weeks in a cast, smelled as if it had crawled in there to die. I asked for a barber and, oddly enough, one came from the hospital shop. He cleared away the stubble, trimmed my moustache and gave me a haircut.