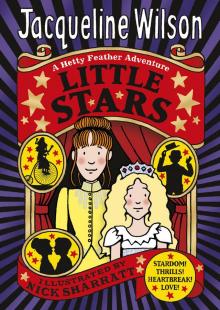

Little Stars

Jacqueline Wilson

ABOUT THE BOOK

Hetty Feather has begun a new chapter in her life story. Escaping from Tanglefield’s Travelling Circus with her friend Diamond, Hetty is determined to find them positions as music-hall artistes.

The pair quickly become the Little Stars of Mrs Ruby’s show at the Cavalcade, alongside many colourful acts – including a friend from Hetty’s past, Flirty Bertie. But the music hall is both thrilling and dangerous, and Hetty must fight to protect her darling Diamond, who longs for a normal childhood. Meanwhile, Hetty struggles with her feelings for Bertie – and for Jem, whom she has never forgotten.

Hetty dreams of a glittering future for herself and Diamond. The bright lights of London beckon – will Hetty become a true star?

Starring a cast of wonderful characters, both old and new, this is the fifth fabulous Hetty Feather story.

To Rhian Harris, with many thanks.

Hetty Feather wouldn’t exist without you.

I WOKE WITH a start, my head hurting, aching all over. For a moment I didn’t know where I was. Indeed, I felt so fuddled I didn’t even know who I was. Hetty Feather, Sapphire Battersea, Emerald Star? I had three names now.

Was I Hetty, curled up in my soft feather bed in the cottage or shivering in the narrow iron bed in the Foundling Hospital? Was I Sapphire, tossing and turning on the servant’s truckle bed in the attic or still as a statue in my mermaid’s costume at the seaside? Was I Emerald, still reeking of fish in my nightgown, or exhausted in my caravan bunk, with Elijah the elephant trumpeting in the distance?

I could hear shouting, thumping, scraping. I must be at Tanglefield’s Circus. Oh Lord, was Diamond in trouble? I had to protect her. Had that evil clown Beppo beaten her cruelly because she’d tumbled during her act?

‘Diamond?’

‘I’m here, Hetty,’ she murmured, clinging to me, strands of her long yellow hair tickling my face.

‘Oh, Diamond, you’re safe!’ I said, holding her tight.

‘Of course I’m safe. We ran away,’ she said sleepily.

We ran away – yes, of course we did. I’d grabbed the clowns’ penny-farthing, little Diamond balanced on my shoulders, and I pedalled and pedalled and we got away from Beppo and Mr Tanglefield. I felt my ear throbbing. Tanglefield had caught the tip of it with his whip, making it bleed. But we’d escaped! We were miles away from the circus camp. We’d fetched up in this little town, and here we were, huddled in a shop doorway near the marketplace.

I gently nudged Diamond to one side and sat up straight, stretching and yawning. I peered around anxiously, worried about the bicycle, but there it was, leaning against the wall beside us. It was still very early, but the market square was full of carts and burly men setting up their stalls with fruit and vegetables. I watched for a minute or two, fascinated by the way their great ham fists delicately arranged a row of apples, a ring of cauliflowers, a circle of salad stuffs upon the fake green grass of their stalls so that they looked like a prize garden in bloom.

One man looked up and saw me watching. He frowned and started walking purposely towards us.

I grabbed Diamond’s arm, giving her a little shake. ‘I think we’d better get going,’ I said urgently, because I trusted very few men.

But as we stumbled to our feet and I tried to right the penny-farthing, he cried out to us. ‘Don’t run away, little girls! You mustn’t be frightened. I don’t mean you any harm. Why, I’ve brought up three little lasses of my own – plus a son, but the less said about him, the better. You look so cold and tired. Let me buy you each a hot drink.’ He seemed genuinely concerned. It was clear by his tone that he thought me not much older than Diamond. It was a curse to me that I was so small and slight, but sometimes it had its advantages.

‘That would be very kind, sir,’ I said.

‘And what are your names, little girls?’

‘I’m Hetty and this is my sister, Ellen-Jane.’ I used our real names. Emerald and Diamond would sound too fancy for this plain market man, and it seemed a wise precaution to keep quiet about our professional names. Mr Tanglefield might try to hunt me down, and Beppo would certainly do his best to find little Diamond. She’d become the star of his Silver Tumblers acrobatic act, a real little crowd-pleaser. He’d paid her father five guineas to own her, body and soul, and he’d certainly got his money’s worth.

I glanced at Diamond, hoping she wouldn’t find it odd that I’d used her old name, but she was beaming. Her face was pale and tear-stained, her hair tangled and her clothes badly creased, but she still looked angelic.

‘Sister!’ she murmured, putting her hand in mine, clearly loving the notion.

I squeezed her hand tight.

‘Aaah!’ said the market man. ‘Bless the little cherub! Well, I’m Sam Perkins, and that’s my stall over there. Perkins, pick of the crop! Finest root vegetables and greens.’ He gave a little bow.

‘Good morning, Mr Perkins,’ I said, bobbing him a curtsy, and giving Diamond’s arm a little tug so she’d do likewise. ‘We’re pleased to meet you too.’

‘Oh, you pets! Ain’t you got lovely manners! But look, the little one’s shivering. Let’s warm you with that hot cup of tea.’

There was a small teashop at the side of the market, open from the crack of dawn for the market trade. We followed in Mr Perkins’s wake. I gave Diamond our little suitcase while I carefully wheeled the penny-farthing. I was reluctant to leave it leaning up against the wall of the teashop.

‘It’ll be safe there, don’t you fret,’ said Mr Perkins. ‘Hey, you – young Alfred!’ he called to a boy at the nearest stall. ‘Keep an eye on this here contraption, will you? Give us a whistle if anyone so much as walks near it.’

Alfred gave a nod and a wave. Mr Perkins was obviously well respected at the market. He led us into the warm steamy interior of the teashop. It was thick with the smell of bacon and sausage, so strong it made us reel. I felt starving hungry. I also had another pressing urge. I went and whispered to the large lady behind the counter, and she let Diamond and me through to her WC at the back of the shop. When we had relieved ourselves, we had a quick wash in the basin and I tried to comb Diamond’s tangled curls with my fingers.

‘There now!’ said Mr Perkins when we came back. ‘Bessie, three mugs of tea and three special breakfasts, if you please.’

‘Certainly, Sam. Are these two your grandchildren then? Hello, dears! Have you come to see your grandpa at his work?’ Bessie asked. She was all over smiles, her round face rosy red, her curly hair damp, her white apron pulled taut over her plumpness.

Mr Perkins led us to a table away from all the other market men. ‘Not mine, Bessie. Two new little friends,’ he said cheerfully.

‘And where do they come from, then?’ Bessie asked.

‘Ah, it’s a long story,’ said Mr Perkins, sitting down beside us. He lowered his voice. ‘I thought you’d maybe want to keep your circumstances to yourselves, rather than broadcast them to all and sundry.’

‘That’s so tactful of you, Mr Perkins,’ I said gratefully.

‘That doesn’t mean that I don’t want to know,’ he said. ‘Not just out of nosiness. I’d like to think I can help in some way. You’re a pair of runaways, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said, because it was pointless denying the obvious.

‘Well, I’ll let you get your breakfasts first, and then I’ll want to hear the whole story,’ said Mr Perkins.

I bent down, unlatched the suitcase and felt for my purse. ‘I can pay for the breakfasts, Mr Perkins. We’re not destitute,’ I said.

He roared with laughter. ‘Bless you, dear, I didn’t think it for a minute. I can see you’re two nicely turned out little ladies. Such fine and fancy dresses clearly cost a pretty penny.’

&nbs

p; I smiled, because I’d made both our outfits myself. I kept my purse in my hand, but Mr Perkins shook his head.

‘Now, pop that purse back in your case. The breakfasts are on the house. Bessie’s a dear friend of mine, and very kind-hearted. A good cook too. A good plate of Bessie-food will put some roses in those peaky little faces.’

It was wonderful food. Beppo had half starved Diamond to keep her as light as possible for her acrobatic tumbling, and I had been feeling so tired and run down these last few months at the circus that I’d barely been able to choke down my own food. But now we both made short work of our bacon, sausage, egg, tomato and fried bread, and had enough room left for several slices of buttered toast with marmalade.

‘Oh, my!’ said Diamond, rubbing her full tummy. ‘Bessie-food is the best food ever!’

‘Did you hear that, Bess? The little lass thinks you’re a rival to Mrs Beeton,’ said Mr Perkins.

‘Better than Mrs Beeton,’ I said. I’d tried several of her recipes with Mrs Briskett when I first went into service, and it had seemed an awful lot of fiddling about for very average results. Or perhaps it was simply my culinary skills that were lacking. I wished I’d had more time with Mama so that she could have taught me. I felt a longing for her as sharp as toothache and bent my head.

‘What is it, lass? Come now, whet your whistle with your tea and tell your Uncle Sam all about it,’ said Mr Perkins, patting my hand in a kindly fashion.

I wished he were really my uncle. I had a moment’s fantasy that he might take a shine to us and treat us like real grandchildren. We would no longer need to try to earn our own livings. I could be a little girl again, safe and cosy, still at school. Diamond would become the pet of the whole family. Mr Perkins would show her that men could be kind instead of cruel. I thought of her father selling her for a handful of silver guineas, Beppo beating her savagely if she made some slight mistake. The tears in my eyes spilled over.

‘Hey, now, don’t you start crying or you’ll set me off. I blub like a baby, I’m warning you,’ said Mr Perkins, pressing his own crumpled handkerchief on me.

I sniffed and dabbed at my eyes fiercely. I told myself I was only tearful because I was tired. I knew Diamond was looking at me anxiously.

I gave her a watery smile, managing to control myself. ‘I’m sorry. I’m being silly,’ I said. I wondered if I dared tell Mr Perkins the whole truth.

‘Are you going to tell me what you two are doing here? Who have you run from? You’ve no need to be frightened now. If it’s anything truly bad and you’re scared someone will come after you, we’ll whisk you over to Sergeant Browning at the police station. He happens to be a pal of mine, and he’ll look after you and keep you safe.’

That brought me to my senses. Sergeant Browning might be Perkins’s pal, but he was still a policeman. If he knew who I really was, then he might well march me straight back to the Foundling Hospital to be disciplined and then sent off into service again. And what about Diamond? Beppo had his official document saying that she belonged to him now. I couldn’t risk that fate for her.

It was better to lie – and through necessity I had become very good at it.

‘It’s nothing like that, Mr Perkins, I promise you. Ellen-Jane and I are sad because we’re grieving for our poor mother. She died of the consumption. She suffered something cruel.’ Tears poured down my face again. I felt bad when I saw the concern on Mr Perkins’s face, but after all, we had both lost our dear mothers, and still sorely missed them.

‘What about your pa, dear? Can’t he manage to look after you two girlies?’

‘Oh, Pa’s a sailor and away at sea,’ I said glibly.

‘So who’s been looking after you two, then?’ he asked.

‘That’s the problem. They put us into a home for destitute girls but it was quite hateful. There was a wicked matron who treated us cruelly and we had to wear hideous brown uniforms with white caps and pinafores and we were punished if we dirtied them. We weren’t allowed to keep our own dolls or story books and they threatened to cut off our hair,’ I said, remembering all too well the regime of the Foundling Hospital.

‘Cut off your pretty hair!’ echoed Mr Perkins, looking at Diamond’s beautiful long blonde curls.

‘And then my sister made some little childish mistake and they threatened her with a beating, so we decided to run away, didn’t we, Ellen-Jane?’ I said.

Diamond nodded, though she was clearly muddled by my account.

‘And no wonder,’ said Mr Perkins. ‘But where are you running to? Do you have any plans? We can’t have you two little girls walking the streets and sleeping rough. There’s all sorts of dangers, especially when you’re such a pretty pair.’

I knew perfectly well that I wasn’t pretty, with my carroty hair and pale peaky face, but Diamond’s beauty was undeniable. I guessed it would trouble him if I said we had plans to join the Cavalcade music hall. I’d been out in the world long enough to know that men might like to enjoy themselves in a music hall, but wouldn’t think it a place for women to work, especially ‘genteel’ girls.

‘We’re going to the Cavalcade,’ Diamond blurted out, before I could stop her.

Mr Perkins looked horrified. ‘You’re never! That den of iniquity! What are you thinking of?’ he said to me, suddenly furious.

Diamond clapped her hands over her mouth. She was always terrified when men lost their tempers. She had so often borne the brunt of Beppo’s fury.

‘Oh, Mr Perkins, please don’t get angry. Diamond is only little, she doesn’t understand. She saw a poster bill and asked what it was all about, and when I told her it was ladies singing and men telling funny stories, she took a fancy to going to see for herself. But of course I’d never dream of taking her to such a place.’

Diamond stared at me, astonished.

‘We have plans, Mr Perkins, don’t you worry,’ I continued hastily. ‘We’re going to stay with our uncle and aunt. We have written to let them know. It is all arranged. We couldn’t cover the entire distance yesterday, but will be there by lunch time today if we set off shortly on our bicycle.’

‘Well, that’s a relief. You’re a rum one, knowing how to pedal that monstrosity. And what does the little one do, run along beside you?’ asked Mr Perkins.

‘I balance on Hetty,’ said Diamond proudly.

‘You never! A little lass like you! Surely that’s highly dangerous?’

Diamond looked at Mr Perkins as if he were a little soft in the head. Balancing on a penny-farthing was a trivial feat compared with hurtling off a springboard and landing on the top of a human column of three boys, the act for which she was famous.

‘Ellen-Jane is brilliant at balancing, I promise you,’ I assured him. Diamond nodded her head eagerly.

‘You’re a droll little pair,’ said Mr Perkins. ‘I still feel anxious about letting you wander off on your own. I’d accompany you myself, but I can’t abandon my stall all day. Perhaps I’ll ask Sergeant Browning if one of his young bobbies can walk along beside you.’

‘Oh no, that’s not at all necessary,’ I said quickly. ‘I dare say Uncle will come and meet us halfway. We will be fine, Mr Perkins. We’re well set up now with our delicious breakfasts. We’ll never forget your kindness.’

We said goodbye, thanked Bessie for our superb meals, and went outside to grapple with the penny-farthing. I couldn’t mount the wretched thing properly with Mr Perkins and half the market watching me. I got my skirts caught, and then, when I clutched my suitcase, I overbalanced and very nearly landed on my head. The boys on the stalls laughed raucously, but Mr Perkins looked worried.

‘My dear Hetty, I think you’re too little to ride that iron monster. How old are you? Ten? Twelve?’ he said.

I wanted to toss my head and tell him firmly that I was fifteen years old and had been entirely independent for a good year, but I didn’t want to disillusion him, especially when he’d been so kind to us. And in spite of my embarrassment and irritation I was also pleas

ed. My childishness had helped when I was Tanglefield’s ringmaster. People were amused by my loud expressive voice, my swaggering air of authority, my overblown introductions, impressed that a little girl could take command.

I needed to appear a child to the manager of the Cavalcade. It was clearly my winning card. Diamond looked much younger than her age too. We could pretend she was a tot of five or six. Folk loved a performing infant. All we had to do was bounce on stage and act cute and they’d start clapping.

This thought buoyed me up – literally so, because at the third attempt I hitched myself neatly onto the saddle, so that Diamond could scramble up after me.

‘Sit behind me, sharing my seat,’ I whispered, because I feared her shoulder stand would look too flamboyant. We were already drawing far too much attention to ourselves.

I freed one hand to give Mr Perkins a little wave, and then started pedalling determinedly.

‘Goodbye, Hetty! Goodbye, Ellen-Jane. You take care now!’ Mr Perkins called, waving his handkerchief at us.

‘Goodbye,’ we chorused, feeling truly sad to leave him.

Diamond was muddled by my glib lies. ‘Are we really going to see our uncle, Hetty?’ she asked. ‘I didn’t even know we had one.’

‘No, Diamond,’ I said patiently. I suddenly wondered if I had a real uncle. Mama had never mentioned having a brother, but then she’d never mentioned her family at all. I’d met her father once, when I was up north finding my father, but this grandfather of mine was such a demented, angry old man I was determined never to go near him again, not even to find out if I had any other family.

It had been a pleasure getting to know my own handsome red-haired fisherman father, though I was less enthusiastic about his new wife. Father had never mentioned a brother or sister either, come to that. I was an only child too, if I didn’t count my two half-siblings.

If I ever married, I resolved to have a whole handful of children, just so they should never feel alone. I knew I could have had dear Jem as a sweetheart and married him some time in the future. He would have made a truly loving husband. And yet I had run away to the circus because I knew, deep down, that I didn’t love him in quite the right way. I was too restless to stay in that little hamlet for the whole of my future life. I wanted excitement, glamour, adventure . . .