The Humanoids- The Complete Tetralogy

Jack Williamson

Jerry eBooks

No copyright 2015 by Jerry eBooks

No rights reserved. All parts of this book may be reproduced in any form and by any means for any purpose without any prior written consent of anyone.

The Humanoids

The Original and Complete Tetralogy

Jack Williamson

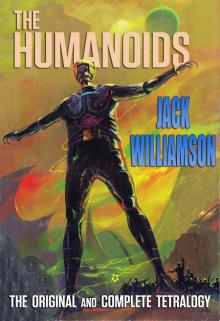

(custom book cover)

Jerry eBooks

Title Page

Source List

Introduction

WITH FOLDED HANDS

. . . AND SEARCHING MIND

THE HUMANOID TOUCH

THE HUMANOID UNIVERSE

About Jack Williamson

SOURCE LIST

With Folded Hands

Astounding Science Fiction

Volume XXXIX, Number 5

July 1947

. . . And Searching Mind

Astounding Science Fiction

Volume LVI, Numbers 1-3

March-May 1948

The Humanoid Touch

Phantasia Press

First Edition

October 1980

The Humanoid Universe

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact

Volume C, Number 6

June 1980

Introduction

ME AND MY HUMANOIDS

The humanoids are small man-shaped robots, all powered and operated from a central computer on the planet Wing IV. Invented in the aftermath of a terrible nuclear war to protect man from his own runaway technology, they are ruled by their own Prime Directive, “To serve and obey, and guard men from harm.”

The problem is that their built-in benevolence goes too far. Alert to the potential harm in nearly every human activity, they don’t let people drive cars, ride bicycles, smoke or drink, engage in unsupervised sex. Doing everything for everybody, they forbid all free action. Their world becomes a luxurious but nightmarish prison of total frustration.

They appear in two stories, a novelette, “With Folded Hands,” and a novel, The Humanoids, originally serialized in John Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction as “. . . And Searching Mind.” The first is probably the better story. I agree with Jim Gunn that the novelette is the best length for most science fiction, with space enough for the full development of an idea but with no demand for the writer to offer final solutions to the problems he raises. “With Folded Hands” says what I wanted to say about the hazards of uncontrolled technology.

It’s the novel that has been misunderstood—or at least interpreted in contradictory ways that I never expected. The reason, I believe, is that it has a second theme, one less obvious than the technological threat but perhaps more significant. The humanoids, seen as symbolic, become a metaphor for a universal human conflict far older than the first machine.

The idea and the original title for the novel were suggested by Campbell. He was generally an optimist, hopeful for progress, convinced that most technological problems could be solved by better technologies. Impressed with the evidence for paranormal powers that Joseph Rhine has reported from Duke University—his own alma mater—he suggested that people unable to use their hands might develop new powers of the mind to outwit the humanoids.

I’m less optimistic than Campbell was, though in the beginning, when the notion of the humanoids first took shape, I assumed that somehow they could be controlled. I had worked for a couple of months on a version of the story in which they were to be finally defeated before I realized that if they were really perfect machines they could never be stopped.

At that point, depressed by my own hopeless vision of mankind enslaved forever by his last best invention, I gave up that draft and wrote a more cheerful novelette, “The Equalizer,” about a different sort of new invention that sets every man completely free.

The optimism of “The Equalizer” nerved me to face the humanoids again. With a new setting and a new viewpoint, I wrote “With Folded Hands,” limiting the story to the frightened resistance and the tragic defeat of a typical man in a typical family in a typical small town, as they take it over. The dark theme, I think, is effectively stated: the best possible machines, designed with the best of intentions, become the ultimate horror.

This bitter pessimism isn’t exactly my own. I seldom write a story just to state a theme, because that sort of emphasis can distort character and plot. The truer theme, I feel, is the one that comes or seems to come out of the story itself, adding force and depth.

Yet I couldn’t quite accept Campbell’s idea that new paraphysical powers would be evolved or discovered to control the humanoids. By definition, as perfect machines, they would run on forever. As the novel came alive in my mind, the vast new human powers turn out to be physical, after all, and hence within the humanoid’s domain. The new effort to stop them ends in an ironic new defeat, with the humanoids now able to seize and rule every human mind. Men become the puppets of their own best machine.

The misunderstanding of the novel comes partly from the way I wrote this ending. To avoid a simple repetition of the conclusion of “With Folded Hands,” I tried a literary experiment. The outcome of the novel, as I saw it, was more than ever hopeless—but I told it from the point of view of people who had been brainwashed to feel happy about the humanoids.

The result was an unexpected ambiguity. No two reviewers saw the ending in quite the same way. Many readers since have found it as bleak as I meant it to be, but more of them have taken the attitudes of the brainwashed victims to be my own.

Harold L. Berger, for example, in his recent study of antiutopian literature, Science Fiction and the New Dark Age, reads “With Folded Hands” just as I intended placing the story, along with Orwell’s 1984, “among the darkest dystopian visions.” When he comes to discuss the novel, however, he raises questions about my “sudden prohumanoid shift.” Is it merely a display of “virtuosity as a storyteller,” or a new belief that “man must submit to the dictatorship of protective technology or be victimized by a destructive one?”

Actually, I’m not entirely displeased with these varied and contradictory responses. Ambiguity has its values. I don’t think any writer can give a really satisfying final answer to such a major human problem as the best use of technology. If he is able just to raise such a question, suggest its significance, and explore the implications of a few possible answers, that’s perhaps enough.

In any case, I think this novel does have another level of meaning, nearer the one that Berger suggests. I think the humanoids, at least for me, are not only a symbol of the ultimate technology but also a metaphor for the old conflict between society and the individual self.

This second meaning struck me years after the novel was written, when I began to realize that its emotional content came from my own very early childhood, a time when I was in conflict with my own parents and other adults as benevolent as the humanoids themselves and relatively as powerful, all forever against me but insisting that they were acting for my own benefit.

Through my first three years, while I was still the only child, we lived on an isolated ranch in the Sierra Madre of northern Mexico, a long day’s ride, as my mother used to say, beyond the end of any road for wheels. That mountain wilderness was almost too much for her, partly because she had too much concern for the infant me. Afraid of untamed Apaches, of scorpions, of mountain lions, even of the bare earth floor, she kept me shut up most of the time in a railed crib, when I wanted freedom at least to crawl on the dirt. I had to love her, because she loved me. As my jailor, however, cruelly breaking my will, she had to be hated.

That must have been my own first plunge into a universal human dilemma. We are all born freedom-seeking animals, but we

cannot live alone. Coming to terms with our fellow beings, with family and playmates, with the school and the law, with our culture and its gods, we all must compromise. A few of us make the bargain easily and make the best of it, win friends and lovers, earn fame and power, become the social masters. Most of us are less successful, our concessions painful, our rewards uncertain, our masters hateful. A rebel few of us, stubbornly yielding nothing, remain defiant till we die.

This social compromise is the price of being human. In the simple animal family, before our prehuman forebears moved out of the forests into the grasslands, the pressures of the struggle must have been minimal, though I suppose already real and painful enough. Step by step, with such great inventions as the bipedal posture and the tool-making hand, the hunting group and the speaking voice, the price grew higher. Ever more complex, society was ever more demanding, remolding the native animal to make the human being.

We have always paid this rising price willingly enough, because the rewards rose with it. Stage by stage, with tools and clothing, with language and writing, we won command of our environment. Showering us with comforts and securities, society has always served us well— so long as we surrendered enough of ourselves.

This hard bargain is the basic stuff of literature and a central issue of literary criticism. Most literature works to socialize us, to curb our outlaw individualism and teach us the ways of the folk, to make us good citizens. Some, however, does defend the native self. A few independent writers, Ibsen for one, have written tragedies about individuals destroyed by giving too much.

In the language of the literary critic, all this becomes the old feud between classicism and romanticism. The classicist is the social man, the accepter of the status quo, the respecter of tradition. His values are reasoned, public, formal. An Ironsmith, he makes the most of his social bargain.

The romanticist is a Forester, the individualist, who cannot compromise. His values are private, unreasoned, intuitive. He regrets the status quo and challenges tradition. Sometimes—if he is very lucky—he can make some creative change in his society. More commonly he only wastes himself.

As I now see this theme in the novel, the humanoids stand for society, for the family and tribe and nation, for teachers and cops and priests, for custom and culture and public opinion, for the whole immense machine that restrains and reshapes our impulses and emotions, always —so we are told—for the common good and our own ultimate benefit.

Forester, in his long and bitter struggle to stop or escape the humanoids, is the native self trapped in the social machine, desperately defending his individuality. At the end of the novel, he and his few forlorn companions have been transformed in spite of themselves into useful social cogs.

The best evidence for the interpretation is the way it explains Frank Ironsmith. All through the novel, he puzzles and alarms Forester because he gets on with the humanoids too well. They let him go where he pleases, wear his own clothes and open his own door, let him smoke and drink, even let him ride his bicycle—activities all decreed too dangerous for Forester.

At the end of the novel, it is Ironsmith who enables the humanoids to expand their powers into the paraphysical. Merely machines, they are not creative—as society itself is not. It is Ironsmith and his like who make the new inventions for them, and Forester comes to regard him as the ultimate traitor to mankind.

Writing the novel, I found a vast delight in the way Ironsmith developed, though at the time I didn’t fully understand him. I think now that he represents the social man, the individual who makes the most of his social compromise. In the ironic outcome, he gets back more than he has ever surrendered. A social master, he enjoys everything the romantic rebel wants and never wins.

This interpretation was clarified for me long after the novel was written, during a study of H. G. Wells and his early science fiction. I was contrasting the careers of Wells and his less lucky friend, George Gissing. Neither, of course, was all classicist or all romanticist. Never fully socialized, Wells was always a critic of his world. In his love affairs, especially, he freely broke traditional codes. In spite of such romantic traits, however, his bargain with society seems to have been uncommonly successful. He enjoyed fame, money, a degree of political influence, the love of beautiful and talented women— all with minimal penalties.

Gissing, on the other hand, was a gifted romantic rebel who refused to compromise. He died young, penniless and bitter, a broken victim of his own rebellion. His tragedy parallels Forester’s, it seems to me; and Wells, with his richer career, seems to have made Ironsmith’s happier bargain.

The parallels are real, in spite of human contradictions. If Wells himself was half romantic rebel, Gissing had a classic regard for tradition. His actual tragic fault, Wells believed, was the classic education that had left him ignorant of science and scornful of progress. Yet, in the outcome, they reversed those roles in a way that illuminates the novel, at least for me.

Seen in this way, The Humanoids becomes vaguely autobiographical. Though I had never met a robot, I was passing when I wrote the book through a shift of social roles, from Forester’s to Ironsmith’s. My early years on isolated ranches had left me an awkward outsider, a lonely individualist. Coming of age on the eve of the great depression, in a world that seemed to have no room for me, I turned back into the life of my own imagination. Existing as an ill-paid science fiction freelance, when science fiction itself had just begun to exist, I had never had a job, never married, never decided to join the world.

Yet I was not the complete romantic rebel. Never very happy as the alienated loner, I had spent two years under psychoanalysis, trying to take stock of myself. I had served as a weather forecaster in the Army Air Forces through

World War II, somewhat surprised at the satisfactions that came from finding a place even in that strongly ordered social world. The stories about the humanoids were written in the year and a half after I got home. With the novel finished, I moved into town from the family ranch, worked for a time at a newspaper job, married, returned to college, eventually became a college professor. Rather late in life, I was joining the human race.

The ambiguities of the novel are probably reflections of my own mixed emotions about this transition. Forester’s desperate war against the humanoids must come from my old longing for total independence, and Ironsmith’s genial dealing with them seems to mirror my own slow acceptance of society—a bargain I certainly don’t regret.

In summary, I’m suggesting that the novel may be read on two different levels. On the first and more obvious, the story says that our best technology will do us in. Read that way, with Frank Ironsmith an enigmatic villain, the ending seems blurred or contradictory. On the second level, it says that society rewards those who accept it and destroys those who don’t, and Ironsmith becomes a not-very-sympathetic hero.

Or so it seems to me. A writer can be his most mistaken critic, and I may be wrong. Communication is never absolute. In the phrase of general semantics, the map is not the territory. Every reader of every author’s map is creating his own new territory, his own unique reflection of what the writer meant to say. I can’t dictate the meaning of The Humanoids, for it has no single meaning. I do hope, however, that these comments will enrich the book for at least a few readers.

—Jack Williamson

April, 1980

WITH FOLDED HANDS

With Folded Hands

Publication Information

Original Cover

Teaser

“With Folded Hands”

RETURN TO MAIN CONTENTS

First appeared in the July 1947 issue of Astounding Science Fiction.

To serve and protect mankind was good: to protect—was to destroy!

Underhill was walking home from the office, because his wife had the car, the afternoon he first met the new mechanicals. His feet were following his usual diagonal path across a weedy vacant block—his wife usually had the car—and his preoccupied mind was reje

cting various impossible ways to meet his notes at the Two Rivers bank, when a new wall stopped him.

The wall wasn’t any common brick or stone, but something sleek and bright and strange. Underhill stared up at a long new building. He felt vaguely annoyed and surprised at this glittering obstruction—it certainly hadn’t been here last week.

Then he saw the thing in the window.

The window itself wasn’t any ordinary glass. The wide, dustless panel was completely transparent, so that only the glowing letters fastened to it showed that it was there at all. The letters made a severe, modernistic sign:

Two Rivers Agency

HUMANOID INSTITUTE

The Perfect Mechanicals

“To Serve and Obey,

And Guard Men from Harm.”

His dim annoyance sharpened, because Underhill was in the mechanicals business himself. Times were already hard enough, and mechanicals were a drug on the market. Androids, mechanoids, electronoids, automatoids, and ordinary robots. Unfortunately, few of them did all the salesmen promised, and the Two Rivers market was already sadly oversaturated.

Underhill sold androids—when he could. His next consignment was due tomorrow, and he didn’t quite know how to meet the bill.

Frowning, he paused to stare at the thing behind that invisible window. He had never seen a humanoid. Like any mechanical not at work, it stood absolutely motionless. Smaller and slimmer than a man. A shining black, its sleek silicone skin had a changing sheen of bronze and metallic blue. Its graceful oval face wore a fixed look of alert and slightly surprised solicitude. Altogether, it was the most beautiful mechanical he had ever seen.

Too small, of course, for much practical utility. He murmured to himself a reassuring quotation from the Android Salesman: “Androids are big—because the makers refuse to sacrifice power, essential functions, or dependability. Androids are your biggest buy!”