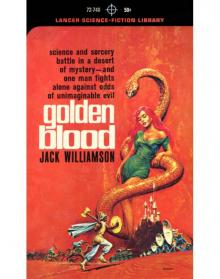

Golden Blood

Jack Williamson

Jack Williamson

Golden Blood

Originally serialized in Weird Tales, April-September 1933

1. THE SECRET LEGION

THE NOONDAY Arabian sun is curiously like moonlight. The eye-searing brilliance of it, like the moon, blots out all color, in pitiless contrast of black and white. The senses withdraw from its drenching flame; and the Arab kaylulah or siesta is a time of supine surrender to supernal day.

Price Durand, sprawled beneath a sun-faded awning on the schooner’s heat-blistered deck, lay in that curious half-sleep in which one dreams, yet knows he dreams, and watches his visions like a play. And Price, the waking part of his mind, was astonished at his dream.

For he saw Anz, the lost city of the legend, where it stood hidden in the desert’s heart. Mighty walls girdled its proud towers, and away from their foot stretched the green palm groves of the great oasis. He saw the gates of Anz open in the dream, massive valves of bronze. A man rode out upon a gigantic white camel, a man in gleaming mail of gold, who carried a heavy ax of yellow metal.

The warrior rode out of the gate, and through the tall palms of the oasis, and into the tawny dunes of the sand-desert. He was reaching for something, and his fingers kept tight upon the helve of the great ax. And the white camel was afraid.

A fly came buzzing about Price’s head, and he sat up, yawning. A damned queer dream, that! He had seen the old city as vividly as if it had actually been before his eyes. His subconscious mind must have been at work on the legend: there had been nothing in the story about a man in golden armor.

Well, it was too hot to worry about a dream, too hot to think at all. He mopped the perspiration from his face, and stared around him with eyes narrowed against the blinding glare.

The Arabian Sea blazed beneath the merciless sun, a plane of molten glass. The blazing sky was tinged with copper; dry, stinging heat drove down from it. A tawny line of sand marked the northern horizon, where the desolate shifting dunes of the Rub’ Al Khali met the incandescent sea. The schooner Iñez, as furtively sinister as her swart Macanese master, lay motionless upon the hot, steely ocean, a mile offshore, her drooping, dingy sails casting narrow and comfortless shadows upon greasy decks.

Price Durand, lounging beneath his tattered awning, was saturated with the haunting loneliness of hot sea and burning sand. The brooding, shadowy hostility of the unknown desert so near flowed about him like a tangible current, silent, sinister.

His emotions had become oddly divided, he was thinking, in the long days since the schooner had left the Red Sea, as if two forces in him were struggling for mastery.

Price Durand, the world-weary soldier of fortune, was afraid of this cruelest and least known of the deserts of the world, but not, of course, to the extent of wishing to abandon the expedition; he was not the sort to quit because he was afraid. But he struggled against the tawny, brooding power of the desert, fiercely determined not to be mastered by its silent spell.

And the other, new-born part of him welcomed the haunting spirit of the desert, surrendered to it gladly. The very loneliness beckoned, the swart cruelty was a mute appeal. The same stern hostility of the land that frightened the old Price Durand was a fascinating allure for the new.

“See Fouad’s coming,” boomed Jacob Garth’s calm voice from the foredeck. “Kept the rendezvous to a day. We’ll be starting inland by Monday.”

Price looked up at Jacob Garth. A huge, gross, red-bearded man, with a deceptive appearance of softness that concealed his iron strength. His skin looked white and smooth; it seemed neither to burn nor tan beneath the sun that had cooked all the others to a chocolate brown.

Holding the binoculars with which he had been scanning the red line of the coast, Jacob Garth wheeled with ponderous ease. He evinced no excitement; his pale blue eyes were cold and emotionless. But his words woke the schooner from sundrenched sleep.

Joao de Castro, the swarthy and slant-eyed Eurasian master, scum of degenerate Macao, burst out of his cabin, shrieked excited questions in Portuguese and broken English. De Castro was small, physically insignificant, holding authority over his crew by sheer force of cutthroat hellishness. Price had no great liking for any of his strangely assorted fellow adventurers; but Joao was the only one of them he actually hated. That hatred was natural, instinctive; it had risen from some deep well of his nature at first sight of the man; and Price knew the little Macanese returned it cordially.

Jacob Garth silenced the feverish questions of the master with a single booming word: “There!”

He handed his binoculars to the little man, pointed at the line of undulating sand across the shimmering, steely sea.

Price’s attention went back to Garth. After three months he knew no more of the man than on the day he had met him. Jacob Garth was a perpetual enigma, a puzzle Price had failed to solve. His broad, tallow-white face was a mask. His mind seemed as deliberate and imperturbable as his massive body. Price had never seen him display any shadow of emotion.

Presumably, Garth was an Englishman. English, at any rate, he spoke, unaccented and with the vocabulary of an educated man. Price imagined that he might be a member of the aristocracy, ruined by the war, and attempting this fantastic expedition to recoup his fortune. But the supposition was unconfirmed.

It was strange, and yet almost amusing, to watch Jacob Garth standing motionless and immutable as a Buddha, while the excitement his words had created ran like a flame over the ship.

The men sprang up from where they had been lounging on the deck, or came running up the companionway, to line the rail in a shouting, jostling throng, oblivious of the beating sun, staring at the horizon of sand.

Price surveyed the line, speculatively. A hard lot, this score of life-toughened adventurers who called themselves the “Secret Legion.” But a hard lot was just what this undertaking demanded; no place here for pampered tenderfeet.

Every man of the “Secret legion” had served in the World War. That was essential, in view of the actual nature of the schooner’s cargo, which was manifested as “agricultural machinery.” None was younger than thirty, and few were more than forty. One, besides Price, was an American; he was Sam Sorrows, a lanky ex-farmer from Kansas. Nine were British, selected by Jacob Garth. The others represented half a dozen European countries. All were men well trained in the use of the implements in the cargo; and all were the sort to use them with desperate courage, in quest of the fabulous treasure Jacob Garth had promised.

With only their naked eyes, the men at the rail could see nothing. Reluctantly, Price got to his feet, crossed the hot deck to where Garth stood. Without a word, the big man took the binoculars from the captain’s trembling hands and handed them to Price.

“Look, beyond the second line of dunes, Mr. Durand.”

Endless ranks of heaving red-sand crests marched across the lenses. Then Price saw the camels, a line of dark specks, creeping across the yellowish flank of a long dune, winding down toward the sea in interminable procession.

“Sure it’s your Arabs?” he asked.

“Of course,” boomed Garth. “This isn’t exactly a main street, you know. And I’ve had dealings with Fouad before. I promised him two hundred and fifty pounds gold a day, for forty mounted warriors and two hundred extra camels. Knew I could depend on him.”

But Price, having heard before of Fouad El Akmet and his renegade band of Bedouin harami or highwaymen, knew that the old sheikh could be depended upon for little save to slit as many throats as possible whenever profitable opportunity offered.

The stinging sun soon drive the men back to the narrow shadows. Stifling silence settled again, and the vast, unfriendly loneliness of the Rub’ Al Khali—the Empty Abode—was flung once more over the little schooner drenching in bl

inding, merciless radiation.

By sunset of the next day the last box and crate had been landed from the schooner and carried up beyond reach of the waves by Fouad’s forty-odd men. The neat, tarpaulin-covered piles stood beside the camp, surrounded by tents and kneeling camels.

Price, guarding the piles with an automatic at his hip, smiled at the consternation that would ensue in certain diplomatic circles if it became known that the “agricultural implements” in these crates had gone into private circulation.

Mentally, he ran over the inventory, chuckling.

Fifty new Lebel rifles, .315 caliber, five-shot, sighted to 2,400 meters, with 50,000 rounds of ammunition.

Four French Hotchkiss machine-guns, air-cooled—an important consideration in desert warfare—also .315 caliber, mounting on tripods, with 60,000 rounds of ammunition in metal strips of thirty rounds.

Two twenty-year-old Krupp mountain guns, which had seen service in several Balkan wars, and five hundred rounds of ammunition, shrapnel and high explosive.

Two Stokes trench mortars, and four hundred ten-pound shells to match.

Four dozen .45 automatics, with ammunition. Ten cases of hand grenades. Five hundred pounds of dynamite, with caps and fuses.

And looming near him, beside a stack of oil and gasoline drums, was the most ambitious weapon of all: a light-armored, three ton army tank, mounting two machine-guns, equipped with wide treads specially designed for operation over a sandy terrain.

Price had wanted to bring an airplane also. But Jacob Garth had opposed the suggestion, without any good reason save that landing and taking off would be difficult in the sand-desert. Price, for once, had deferred, without suspecting the motive of the other’s opposition.

Many weeks of cautious, anxious effort, and many thousands of dollars—Price’s money—had been paid for this paraphernalia of modern war, to equip the little band of hard-faced men who called themselves the “Secret Legion.”

From his place by the tarpaulin-covered crates, Price watched Jacob Garth coming away from the empty schooner. He noticed curiously that Garth had brought all the men from her, even Joao de Castro, her swarthy, pock-marked little captain. As the boat neared the sand, he saw that Garth and de Castro were quarreling; or rather that the little Eurasian was screaming shrill invective at the big man, who appeared placidly unconscious of him.

Price was wondering why no watch had been left aboard, when he saw the anchored schooner quiver abruptly. A muffled detonation rolled from her across the quiet sea. Price saw debris lift slowly from the deck, and yellow smoke spurt from ports and hatches.

With a curious silent deliberation, the Iñez listed to port, lifted her black bow into the air, and slipped down by the stern.

Then Jacob Garth’s booming voice drowned the lurid protestation of the enraged captain: “We won’t need the ship out in the desert. And I didn’t want her tempting anybody to turn back. When we find the gold, de Castro, you’ll be able to buy the Majestic, if you want!”

2. THE YELLOW BLADE

JACOB GARTH had come to Price Durand three months before, at a bar in Port Said—a giant of a man, grossly fat, his pouchy, pallid face covered with a tangle of red beard. His once-white linens were soiled, limp with sweat; the sun-helmet pushed back on his head was battered, sweat-sodden.

The man possessed a puzzling strength. In his pale-blue, deeply sunk eyes was something hard and cold, a strange glint of will and power. His great, thick hand was not soft, as Price had expected; its grasp was crushing.

“Durand, aren’t you?” he had greeted Price, his deep voice richly resonant. Keenly his pale eyes appraised Price’s six-feet-two of solid, red-headed body; penetratingly his cold eyes met Price’s unwavering, deep-blue ones.

Price studied him in return, found something to pique his curiosity. He nodded.

“I understand you are the sort who can be called a soldier of fortune?”

“Perhaps,” Price admitted. “I have cultivated a certain taste for excitement.”

“I have something that should interest you.”

“Yes?” Price waited.

“You have heard the desert tales of Anz? I don’t mean the village of Anz in North Arabia. The Anz of the lost oasis, beyond the Jebel Harb range.”

“Yes, I know the Arab legends, of Magainma and other lost cities of the central desert. New Arabian Nights.”

“No, Durand.” Garth lowered his mellow voice. “The Bedouin tales of Anz, fantastic as they are, are based on truth. Most folk-tales are. Even the Arabian Nights you mention have a core of true history. But I’ve something more than hearsay to go on. If you will be so kind as to accompany me aboard my schooner, I’ll give you the details. The Iñez—down in the outer basin, by the breakwater.”

“Why not here?” Price motioned to a table in the corner.

“There are certain articles I want to show you, by way of evidence. And—well, I don’t care to be overheard.”

By reputation Price knew the Iñez and her swarthy Macanese master—and knew nothing good of either. Any enterprise in which they were involved promised dubious adventure. But in his present mood, restless, weary of the world, that was not to his distaste.

He nodded to the big man.

Joao de Castro welcomed Price aboard, with a twisted smile upon his swart face, which had been so eaten away by smallpox that it was hairless. The dark, oblique eyes of the little Eurasian went fleetingly to Jacob Garth, and Price caught a furtive question in them. The big man pushed by him, almost roughly, led the way to a dingy cabin, amidships.

Locking the door behind them, he turned to face Price with hard, pale eyes.

“It’s understood you say nothing of this, unless you accept my proposition.”

“Very well.”

He studied Price again, nodded. “I trust you.”

He made Price sit down, while he set a bottle of whisky and two glasses upon the cabin table. Price refused the drink, and Jacob Garth said abruptly:

“Suppose you tell me what you know of Anz—the lost Anz.”

“Well, simply the usual story. That the inner desert used to be fertile, or at least inhabitable. That it was ruled by a great city named Anz. That the spreading deserts cut the city off from the world a thousand years or so ago.

“It’s just what might be expected, considering the Arab imagination, and the fact that southern Arabia is the biggest blank spot on the map, outside the polar regions.”

Jacob Garth spoke slowly, in his deep, passionless tones:

“Durand, that legend, as you have outlined it, is true. Anz exists. It is still inhabited—or at least the old oasis is. And it is the richest city in the world. Loot for an army.”

“I’ve heard men say such thing before,” Price observed. “Do you know?”

“You may judge the evidence. I’ve been exploring the fringes of the Rub’ Al Khali for twelve years—ever since the war. I’ve lived with the Bedouins, and run down a thousand legends. And most of them turned out to be simply distorted versions of the story of Anz.

“And, Durand, I’ve been as far as the Jebel Harb range.”

That statement raised Price’s estimation of the man. He knew that these mountains were considered as mythical as the lost city beyond them. If Jacob Garth had seen them, he must be far more than the unwieldy mass of flesh that he appeared.

“I had five men,” he went on. “We had rifles. But we couldn’t pass the Jebel Harb. Durand, those mountains were guarded! I fancy the people of Anz know more about the outside world than we know about them. And they aren’t anxious to resume communications.

“We had rifles. But they attacked us with weapons that—well, the details are rather unbelievable. But the five with me were brave men, and I came back alone, though not altogether empty-handed. The evidence I spoke of.”

Moving with a certain cat-like ease, despite his gross bulk, Jacob Garth opened a locker and brought Price a roll of parchment—a long, narrow strip of cured skin, dry,

cracked, the writing upon it fading with the centuries.

“A bit faint, but legible,” said Garth. “Do you read Spanish?”

“After a fashion. Modern Spanish.”

“This is fair Castilian.”

Price took it with eager fingers, unrolled it carefully, and scanned the ancient characters.

“Mayo del Año 1519,” it was dated [May, of the year 1519].

The manuscript was a brief autobiography of one Fernando Jesus de Quadra y Vargas. Born in Seville about 1480, he was forced to flee to Portugal at the age of twenty-two, as a result of circumstances that he did not detail.

Entering the maritime service of King Manoel, he was a member of the Portuguese expedition under Alfonso de Albuquerque, which seized the east coast of Arabia in 1508. There, becoming for the second time involved in difficulties that he did not describe, he deserted Albuquerque, only to be immediately captured and enslaved by the Arabs.

After some years, having escaped his captors, and not daring to return to the Portuguese settlements, he had set out, upon a stolen camel, to cross Arabia, in the direction of his native Spain.

“Great hardships attended me,” he related, “for want of water, in a heathen land where the true God is not known, nor even the prophet of the infidel. For many weeks I drank naught save the milk of my she-camel, which fed upon the thorns of the cruel desert.

“Then I came into a region of hot sand, where the camel died for want of water and fodder. I pushed onward on foot, and by the blessing of the Virgin Mary did come into the golden land.

“I found refreshment at a city beside groves of palms. In most hellish idolatry did I find these people, who call themselves the Beni Anz. They worship beings of living gold, which haunt a mountain near the city, and dwell in a house of gold on that mountain.

“These beings, the golden folk, took me captive to the mountain, where I saw the idols, which are a tiger and a great snake that live and move, though they are of yellow gold. A man of gold, who is the priest of the snake, did question me, and then tear out my tongue, and make me a slave.