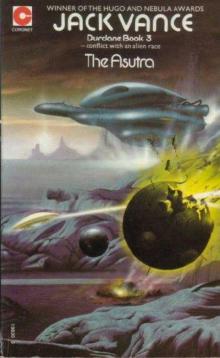

The Asutra

Jack Vance

The Asutra

Jack Vance

Far to the south of the swampy middle region and beyond the ken of most of the people of Shant, lay Caraz, the wild continent, peopled by exiles, nomads and slave traders.

Jack Vance

The Asutra

The third book in the Durdane series, 1974

CHAPTER 1

The Roguskhoi and their dominant asutra had been expelled from Shant. Belabored on the ground by the Brave Free Men, tormented from above by the Flyers of Shant, the Roguskhoi had retreated south, across the Great Salt Bog into Palasedrans. In a dismal valley the horde had been destroyed, with only a handful of chieftains escaping in a remarkable red-bronze spaceship-and so the strange invasion of Shant had come to an end.

For Gastel Etzwane the victory brought a temporary joy after which he fell into a dour and introspective mood. He became aware of a vast aversion to responsibility, to public activity in general; he marveled that he had functioned as well and as long as he had. Returning to Garwiy he took himself from the Council of Purple Men with almost offensive abruptness; he became Gastel Etzwane the musician: so much, no more. At once his spirits soared; he felt free and whole. Two days the mood persisted, then waned as the question What now? found no natural or easy response.

On a hazy autumn morning, with the three suns lazing behind self-generated disks of milk-white, pink, and blue nimbus, Etzwane walked along Galias Avenue. Tape trees trailed purple and gray ribbons about his head; beside him moved the Jardeen River on its way to the Sualle. Other folk strolled along Galias Avenue, but none took notice of the man who so recently had ruled their lives. As Anome, Etzwane of necessity had avoided notoriety; he was not a conspicuous man in any event. He moved with economy, spoke in a flat voice, used no gesticulations, all of which made for a somber force disproportionate to his years. When Etzwane looked in a mirror he often felt a discord between his image, which was saturnine, even a trifle grim, and what he felt to be his true self: a being beset by doubts, shivered by passions, jerked here and there by irrational exhilarations; a person over susceptible to charm and beauty, wistful with longing for the unattainable. So Etzwane half-seriously regarded himself. Only when he played music did he feel a convergence of his incongruous parts.

What now?

He had long taken the answer for granted: he would rejoin Frolitz and the Pink-Black-Azure-Deep Greeners. Now he was not so sure, and he halted to watch broken strands from the tape trees drifting along the river. The old music sounded in his mind far away, a wind blowing out of his youth.

He turned away from the river and continued along the avenue, and presently came upon a three-storied structure of black and gray-green glass with heavy mulberry lenses bulging over the street: Fontenay's Inn, which put Etzwane in mind of Ifness, Earthman and Research Fellow of the Historical Institute. After the destruction of the Roguskhoi he and Ifness had flown by balloon across Shant to Garwiy. Ifness carried a bottle containing an asutra taken from the corpse of a Roguskhoi chieftain. The creature resembled a large insect, eight inches long and four inches in thickness: a hybrid of ant and tarantula, mingled with something unimaginable. Six arms, each terminating in three clever palps, depended from the torso. At one end ridges of purple-brown chitin protected the optical process: three oil-black balls in shallow cavities tufted with hair. Below trembled feeder mechanisms and a cluster of mandibles. During the Journey Ifness occasionally tapped on the glass, to which the asutra returned only a flicker of the optical organs. Etzwane found the scrutiny unnerving; somewhere within the glossy torso subtle processes were occurring: ratiocination, or an equivalent operation; hate, or a sensation analogous.

Ifness refused to speculate upon the nature of the asutra. "Guesses are of no value. The facts, as we know them, are ambiguous."

The asutra tried to destroy the folk of Shant," declared Etzwane. "Is this not significant?"

Ifness only shrugged and looked out across the purple distances of Canton Shade. They now sailed close-hauled into a north wind, bucking and sliding as the winch-tender coaxed the best from the Conseil, a notoriously cranky balloon.

Etzwane attempted another question. "You examined the asutra you took from Sajarano; what did you learn?"

Ifness spoke in a measured voice. "The asutra metabolism is unusual and beyond the scope of my analysis. They seem a congenitally parasitical form of life, to judge from the feeding apparatus. I have discovered no disposition to communicate, or perhaps the creatures use a method too subtle for my comprehension. They enjoy the use of paper and pencil and make neat geometrical patterns, sometimes of considerable complication but no obvious meaning. They show ingenuity in solving problems and appear to be both patient and methodical."

"How did you learn all this?" demanded Etzwane.

"I devised tests. It is all a matter of presenting inducements."

"Such as?"

"The possibility of freedom. The avoidance of discomfort."

Etzwane, faintly disgusted, mulled the matter over for a period. Presently he asked, "What do you intend to do now? Will you return to Earth?"

Ifness looked up into the lavender sky, as if taking note of some far destination. "I hope to continue my inquiries; I have much to gain and little to lose. With equal certainty I will encounter official discouragement. My nominal superior, Dasconetta, has nothing to gain and much to lose."

Curious, thought Etzwane; was this the way things went on Earth? The Historical Institute imposed a rigorous discipline upon its Fellows, enjoining absolute detachment from the affairs of the world under examination. So much he knew of Ifness, his background, and his work. Little enough, everything considered.

The journey proceeded. Ifness read from The Kingdoms of Old Caraz; Etzwane maintained a half-resentful silence. The Conseil spun up the slot; cantons Erevan, Maiy, Conduce, Jardeen, Wild Rose passed below and disappeared into the autumn murk. The Jardeen Gap opened ahead; the Ushkadel rose to either side; the Conseil blew along the Vale of Silence, through the gap, and so to South Station under the astounding towers of Garwiy.

The station gang hauled the Conseil down to the platform; Ifness alighted, and with a polite nod for Etzwane set off across the plaza.

In a sardonic fury Etzwane watched the spare figure disappear into the crowd. Ifness clearly meant to avoid even the most casual of relationships. Now, two days later, looking across Galias Avenue, Etzwane was once again reminded of Ifness. He crossed the avenue and entered Fontenay's Inn.

The day-room was quiet; a few figures sat here and there in the shadows musing over their mugs. Etzwane went to the counter, where he was attended by Fon-tenay himself. "Well then: it's Etzwane the musician! If you and your khitan are seeking a place, it can't be done. Master Hesselrode and his Scarlet-Mauve-Whiters work the stand. No offense intended; you scratch with the best of them. Accept a mug of Wild Rose ale, at no charge."

Etzwane raised the mug. "My best regards. " He drank. The old life had not been so bad after all. He looked around the chamber. There: the low platform where so often he had played music; the table where he had met lovely Jurjin of Xhiallinen; the nook where Ifness had waited for the Faceless Man. In every quarter hung memories which now seemed unreal; the world had become sane and ordinary… Etzwane peered across the room. In the far corner a tall, white-haired man of uncertain age sat making entries into a notebook. Mulberry light from a high bull's-eye played around him; as Etzwane watched, the man raised a goblet to his lips and sipped. Etzwane turned to Fontenay. "The man in the far alcove-what of him?"

Fontenay glanced across the room. "Isn't that the gentleman Ifness? He uses my front suite. An odd type, stern and solitary, but his money is as downright as sweat. He's from Canton Cape, or so I gather."

"I believe I know the gen

tleman. " Etzwane took his mug and walked across the chamber. Ifness noted his approach sidewise, from the corner of his eve. Deliberately he closed his notebook and sipped from his goblet of ice water. Etzwane gave a polite salute and seated himself; had he waited for an invitation, Ifness might well have kept him standing. "On impulse I stepped in, to recall our adventures together," said Etzwane, "and I find you engaged at the same occupation."

Ifness' lips twitched. "Sentimentality has misled you. I am here because convenient lodging is available and because I can work, usually without interruption. What of you? Have you no official duties to occupy you?"

"None whatever," said Etzwane. "I have resigned my connection with the Purple Men."

"You have earned your liberty," said Ifness in a nasal monotone. "I wish you the pleasure of it. And now "-With meaningful exactitude he arranged his notebook.

"I am not reconciled to idleness," said Etzwane. "It occurs to me that I might be able to work with you."

Ifness arched his eyebrows. "I am not sure that I understand your proposal."

"It is simple enough," said Etzwane. "You are a Fellow of the Historical Institute; you perform research on Durdane and elsewhere; you could use my assistance. We have worked together before; why should we not continue to do so?"

Ifness spoke in a crisp voice. "The concept is impractical. My work for the most part is solitary, and occasionally takes me off-planet, which of course- "

Etzwane held up his hand. 'This is precisely my goal, " he declared, though the idea had never formed itself in terms quite so concrete. "I know Shant well; I have traveled Palasedras; Caraz is a wilderness; I am anxious to visit other worlds."

"These are natural and normal yearnings," said Ifness. "Nevertheless, you must make other arrangements."

Etzwane pensively drank ale. Ifness watched stonily sidewise. Etzwane asked, "You still study the asutra?"

"I do."

"You feel that they have not yet done with Shant?"

"I am convinced of nothing. " Ifness spoke in his didactic monotone. The asutra tested a biological weapon against the men of Shant. The weapon-which is to say, the Roguskhoi-failed because of crudities in execution, but no doubt served its purpose; the asutra are now better informed. Their options are still numerous. They can continue their experiments, using different weapons. On the other hand they may decide to expunge the human presence on Durdane altogether."

Etzwane had no comment to make. He drained his mug and in spite of Ifness' disapprobation signaled Fontenay for replenishment. "You are still trying to communicate with the asutra?"

They are all dead."

"And you made no progress?"

"Essentially none."

"Do you plan to capture others?"

Ifness gave him a cool smile. "My goals are more modest than you suspect. I am concerned principally for my status in the Institute, that I may enjoy my accustomed perquisites. Your interests and mine engage at very few points."

Etzwane scowled and drummed his fingers on the table. "You prefer that the asutra do not destroy Durdane?"

"As an abstract ideal I will embrace this proposition."

"The situation itself is not abstract," Etzwane pointed out. "The Roguskhoi have killed thousands! If they won here they might go on to attack the Earth worlds."

"The thesis is somewhat broad," said Ifness. "I have put it forward as a possibility. My associates, however, incline to other views."

"How can there be doubt? " Etzwane demanded. "The Roguskhoi are or were an aggressive force."

"So it would seem, but against whom? The Earth worlds? Ridiculous; how could they avail against civilized weaponry? " Ifness made an abrupt gesture. "Now please excuse me; a certain Dasconetta asserts his status at my expense, and I must consider the matter. It was pleasant to have seen you…"

Etzwane leaned forward. "Have you identified the asutra home-world?"

Ifness gave his head an impatient shake. "It might be one of twenty thousand, probably off toward the center of the galaxy."

"Should we not seek out this world, to study it at close hand?"

"Yes, yes; of course. " Ifness opened his journal.

Etzwane rose to his feet. "I wish you success in your struggle for status."

"Thank you."

Etzwane returned across the room. He drank another mug of ale, glowering back toward Ifness, who serenely sipped ice water and made notes in his journal.

Etzwane left Fontenay's Inn and continued north beside the Jardeen, pondering a possibility which Ifness himself might not have considered… He turned aside into the Avenue of Purple Gorgons, where he caught a diligence to the Corporation Plaza. He alighted at the Jurisdictionary and climbed to the offices of the Intelligence Agency on the second floor. The director was Aun Sharah, a handsome man, subtle and soft-spoken, with an Aesthete's penchant for casual elegance. Today he wore a suave robe of gray over a midnight blue body-suit; a star sapphire dangled from his left ear by a silver chain. He greeted Etzwane affably but with a wary deference that reflected their previous differences. "I understand that you are once again an ordinary citizen," said Aun Sharah. The metamorphosis was swift. Has it been complete?"

"Absolutely; I am a different person," said Etzwane. "When I think over the past year I wonder at myself."

"You have surprised many folk," said Aun Sharah in a dry voice. "Including myself " He leaned back in his chair. "What now? Is it to be music once more?"

"Not just yet. I am unsettled and restless, and I am now interested in Caraz."

"The subject is large," said Aun Sharah in his easy, half-facetious manner. "However, your lifetime lies before you."

"My interest is not all-embracing," said Etzwane.' "I merely wonder if Roguskhoi have ever been seen in Caraz."

Aun Sharah gazed reflectively at Etzwane. "Your term as private citizen has quickly run its course."

Etzwane ignored the remark. "Here are my thoughts. The Roguskhoi were tested in Shant and defeated. So much we know. But what of Caraz? Perhaps they were originally deployed in Caraz; perhaps a new horde is in formation. A dozen possibilities suggest themselves, including the chance that nothing whatever has happened."

"True," said Aun Sharah. "Our intelligence is essentially local. Still, on the other hand, what can we do? We strain to encompass the work already required of us."

"In Caraz news drifts down the rivers. At the seaports mariners learn of events occurring far inland. What if you circulated your men along the docks and through the waterfront taverns, to find what might be the news from Caraz?"

"The idea has value," said Aun Sharah. "I will issue such an order. Three days should suffice, at least for a preliminary survey."

CHAPTER 2

The thin, dark, solitary boy who had taken to himself the name of Gastel Etzwane [1] had become a hollow-cheeked young man with an intense and luminous gaze. When Etzwane played music the corners of his mouth rose to bring a poetic melancholy to his otherwise saturnine features; otherwise his demeanor was quiet and controlled beyond the ordinary. Etzwane had no intimates save perhaps old Frolitz the musician, who thought him mad…

On the day following his visit to the Jurisdictionary he received a message from Aun Sharah. 'The investigation has yielded immediate information, in which I am sure you will be interested. Please call at your convenience."

Etzwane went at once to the Jurisdictionary.

Aun Sharah took him to a chamber high in one of the sixth-level cupolas. Four-foot-thick sky lenses of water-green glass softened the lavender sunlight and intensified the colors of the Canton Glirris rug. The room contained a single table twenty feet in diameter, supporting a massive contour map. Approaching, Etzwane saw a surprisingly detailed representation of Caraz. Mountains were carved from pale Canton Faible amber, with inlaid quartz to indicate the presence of snow and ice. Silver threads and ribbons indicated the rivers; the plains were gray-purple slate; cloth in various textures and colors represented forests and swamps. Shant a

nd Palasedra appeared as incidental islands off the eastern flank.

Aun Sharah walked slowly along the northern edge of the table. "Last night," he said, "a local Discriminator [2] brought in a seaman from the Gyrmont docks. He told a strange tale indeed, which he had heard from a bargeman at Erbol, here at the mouth of the Keba River. " Aun Sharah put his finger down on the map. The bargeman had floated a load of sulfur down from this area up here "-Aun Sharah touched a spot two thousand miles inland- "which is known as Burnoun. About here is a settlement, Shillinsk; it is not shown… At Shillinsk the bargeman spoke to nomad traders from the west, beyond these mountains, the Kuzi Kaza…"

Etzwane returned to Fontenay's Inn in a diligence, to meet Ifness on his way out the door. Ifness gave him a distant nod and would have gone his way had not Etzwane stepped in front of him. "A single moment of your time."

Ifness paused, frowning. "What do you require?"

"You mentioned a certain Dasconetta. He would be a person of authority?"

Ifness looked at Etzwane sidelong. "He occupies a responsible post, yes."

"How can I get in touch with Dasconetta?"

Ifness reflected. "In theory, several methods exist. Practically, you would be forced to work through me."

"Very well; be so good as to put me into contact with Dasconetta."

Ifness gave a wintry chuckle. "Matters are not all that simple. I suggest that you prepare a brief exposition of your business. You will submit this to me. In due course I will be in contact with Dasconetta, at which time I may be able to transmit your message, assuming, naturally, that I find it neither tendentious nor trivial."

"All very well," said Etzwane, "but the matter is urgent. He will be sure to complain at any delay."

Ifness spoke in a measured voice. "I doubt if you are capable of predicting Dasconetta's reactions. The man makes a fad of unpredictability."